Creating an Effective Child Welfare System

Introduction

Editor's note: The following is the third chapter of the book Urban Policy Frontiers published by the Manhattan Institute.

If the nation had deliberately designed a system that would frustrate the professionals who staff it, anger the public who finance it, and abandon the children who depend on it, it could not have done a better job than the present child welfare system.

The indictment that opens this paper could have been written anytime in the past few months or years in the United States. It could have been written in New York City, for example, after the death of Zymere Perkins in September 2016, or Jaden Jordan in November 2016, or Bianca Abdul in March 2017, or the grievous injury to Kadiha Marrow in April 2017.[1]

New York’s child welfare agency is not the only one that could be criticized for failing to protect children. In Los Angeles, four former L.A. County social workers are to stand trial for the 2013 death of eight-year-old Gabriel Fernandez. The four were supposed to protect the boy, who was in the care of his mother and her boyfriend. But Fernandez was found tortured to death—burned, shot with BB pellets, and doused in pepper spray.[2]

In my own city of Philadelphia, 17 individuals were convicted of, or pled guilty to, a range of charges, from third-degree murder to perjury, in the starvation death of 14-year-old Danieal Kelly.[3] Among the 17 individuals were:

Dana Poindexter, Department of Human Services (DHS) intake worker convicted of child endangering, recklessly endangerment, and perjury. Sentenced to two and a half to five years in prison.

Laura Sommerer, DHS social worker: pled guilty to child endangerment. Sentenced to four years’ probation.

Julius Murray, caseworker for the social-services contractor MultiEthnic Behavioral Health: pled guilty to involuntary manslaughter, conspiracy, and child endangerment. Also convicted of health-care fraud. Sentenced to four to eight years in prison for manslaughter, conspiracy, and endangerment; sentenced to 11 years in prison for health-care fraud.

Mickal Kamuvaka, MultiEthnic Behavioral Health CEO: convicted of involuntary manslaughter, child endangerment, perjury, criminal conspiracy, and forgery. Sentenced to 17.5 years in prison.[4]

The inability to protect endangered children is not limited to large urban centers. In Rhode Island, the state Department of Children, Youth and Families admitted that, in April 2016, nearly twothirds (63%) of its kinship placement homes were unlicensed. Unlicensed homes can put children at risk, as kin (relatives) who provide foster care have not completed the required training. In North Dakota, five-year-old Amanda Froistad was sexually abused and then killed by her father, even though reports of suspected maltreatment were filed in both South Dakota and North Dakota. Unbelievably, each state’s child protective service agency said that it was the other state’s responsibility to carry out the investigation—and no investigation was conducted up to the time of Amanda’s death.[5]

What makes the opening statement of this paper even more disturbing is that it was not written in 2017, or 2016, or even 2000. It is a conclusion that was reached by the U.S. National Commission on Children in 1991.[6]

Changes and improvements have occurred in the American child welfare system in the last 25 years, but what was true a quarter-century ago is true today: the American child welfare system is still a frustrating, dysfunctional system that cannot ensure that the children who most need protection will be safe.

What is to blame? The usual suspects have all been rounded up, and still the system fails to protect children. Government has responded to tragedies with more funding and increases in staff, forming blue-ribbon commissions, replacing administrators, reorganizing agencies, and even changing the names of agencies—but there are no significant changes in the capacity to protect children and ensure their well-being. The same lame excuses are offered—for example, “the child fell through the cracks”—and the tragedies continue.

Having been in the field of child welfare for four decades, I have spoken and written often about the failings of the child welfare system. But until now, I have never been so bold as to state the following: Either we do not want to truly protect children and ensure their safety and well-being, or we do not know how to protect children and ensure their well-being.

Typically, I dismiss the complaint about insufficient funding as one of the “usual suspects” rounded up to explain the system’s shortcomings. But as I will explain below, there is one legitimate reason to take up the issue of funding, not necessarily because it is inadequate but because laws that rigidly limit how funding is used do restrict child welfare systems’ effectiveness.

We Do Not Want to Protect Children

Let me begin with my most controversial statement: we do not really want to truly protect children. It is based on a number of key points. First, parental rights have priority in child and family jurisprudence. A series of Supreme Court decisions—from Smith v. Organization of Foster Families for Equality and Reform, 431 U.S. 816 (1977), to Santosky v. Kramer, 455 U.S. 745 (1982)—limits the state’s ability to intervene in the raising of children by their parents, and it sets a high bar for states that wish to terminate parental rights. Nor is this wrong. Upholding parents’ liberty interest to raise their children without unwarranted government interference is appropriate, as is a high bar for terminating parental rights.

Federal law also bolsters parental rights. The Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980[7] primarily provides states with funds for out-of-home placement but includes the requirement that states make “reasonable efforts” to keep children with their birth parents or safely reunify children from out-of-home placement prior to seeking to terminate parental rights.

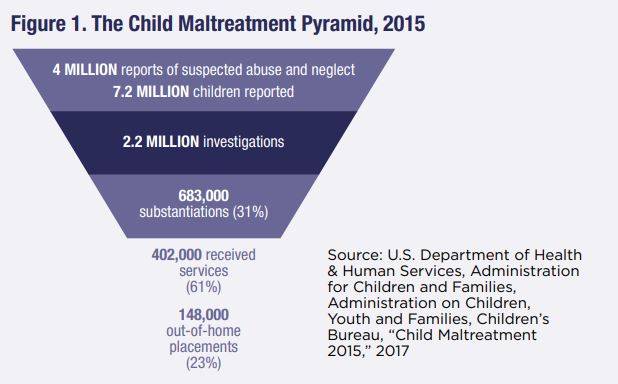

The actual functioning of the child protective service system illustrates how low the likelihood is that a child who is suspected of being the victim of maltreatment will actually be placed in foster care (Figure 1). Despite anecdotal critiques that child protective service agencies are too quick to remove children from homes,[8] the data indicate that the vast majority of reports and the majority of substantiated reports of child maltreatment do not result in the removal of a child from his or her parents.

Last and perhaps most important, the culture of the American child welfare system sees parents as the clients and family preservation as the core goal of child protective services. Law professor Elizabeth Bartholet, in two key publications,[9] summarizes how, for the past three decades, advocates, policymakers, foundations, and agency administrators have privileged supporting and preserving parents over the safety of children.

To be fair, those on the side of family preservation hold fast to the value that children do best when raised by their birth parents and close family members. And to bolster the value of family preservation, members of what Bartholet refers to as the “racial disproportionality movement”[10] use data on the race of children removed from their families as a club to try to limit such removals.

The second approach of the family-preservation advocates is to continue rolling out ever new interventions, such as Intensive Family Preservation Services, Family Group Conferencing, and Alternative Response with claims that such interventions can both preserve families and ensure the safety of children. By the time there are data to disprove the claim of effectiveness of a family preservation intervention, a new intervention is rolled out with the same claims.[11]

A final mainstay of the effort to preserve families is the claim that, with adequate resources and if done properly, child welfare agencies can preserve families as well as ensure the safety of children.

Anecdotal evidence, such as the cases that open this paper, disproves the claim that families can be preserved and children kept safe. The claim violates the laws of probability theory: it is impossible to both reduce false positives (concluding that a child is at risk of abuse when the child is not) and false negatives (concluding that the child is safe when the child is at risk). Choosing the parent as client can significantly disadvantage the safety of the child. Choosing the child as client reduces parental rights. Child welfare agencies must choose the errors that they are willing to tolerate.

By focusing on the parent as the client of the child welfare system and privileging parents’ rights, child welfare systems in practice hold children’s development hostage while waiting and hoping that parents will engage in services and that the services will be effective. This system chooses not to ensure the safety and well-being of children in harm’s way.

We Do Not Know How to Protect Children

Undoubtedly, many will push back strongly, even in anger, against my claim that the American child welfare system as a whole does not want to protect children. My second argument is that child welfare systems do not know how to protect children.

Decision Making

While billions of dollars are spent on supporting children in foster care and services to assist parents—including parenting classes and drug-treatment programs—the most important component and task of the child welfare system in the United States is decision making. I envision the child welfare system as a series of nine gates that begins with the decision to report suspected child abuse and ends with the decision to close the case—through a reunification (the most common outcome) or by termination of parental rights.

No matter how skilled and experienced the decision maker, the actual tools that are available for decision making are not remotely up to the task. In the vast majority of cases and in the vast majority of decisions—decisions as to whether to report a case of suspected maltreatment, whether to substantiate the report, whether to remove the child from the home, and how to close the case—the main tool is clinical judgment. What we know about clinical judgment is that its accuracy is no better than chance, and it introduces bias, such as racism and classism, into the decision-making process.[12]

While there have been some modest advancements in developing actuarial tools for assessing safety and risk and to inform decisions, the child welfare field continues to be reluctant to replace clinical judgment with any of them.

The most recent development in decision making is predictive analytics,[13] or “big data.” Predictive analytics holds much greater promise of improving child welfare decision making than do clinical judgment, consensus risk assessment, and older forms of actuarial risk assessment such as structured decision making. But the child welfare field is slow to embrace this tool. The major concern is profiling: critics worry about minorities and poor families being unfairly profiled by statistical tools—although, of course, such families are already profiled by clinical judgment. Since predictive analytics validates the algorithms with actual data, initial biases will be factored out over time. Nonetheless, the child welfare field, with few exceptions (Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, and Los Angeles County), seems to prefer the bias of clinical judgment to the potential of predictive analytics.[14]

Prevention and Intervention

Currently, the best-tested and validated tool available to the child welfare system for the prevention of child maltreatment is the Nurse-Family Partnership, which involves trained nurses making home visits to low-income mothers who have no previous live births.[15] The visiting nurses have three goals: (1) to improve the outcome of the pregnancy by helping women with prenatal health; (2) to improve the child’s health and development by helping parents provide more sensitive and competent child care; and (3) to improve the parental life course by helping parents plan future pregnancies. David Olds and his colleagues have spent nearly three decades evaluating the effectiveness of the Nurse-Family Partnership program, including three separate random clinical trials with different populations. The program has positive effects: fewer childhood injuries and ingestions that may be associated with child abuse; and fewer substantiated reports of child maltreatment by participating parents.[16]

The child welfare system has developed an extensive menu of interventions. Almost every case file I have reviewed requires parents to attend parenting classes. As a large proportion of caregivers who become involved in the child welfare system have substance abuse issues, substance abuse treatment is a standard intervention. Intensive Family Preservation Services, Family Group Conferencing, and Alternative Response (all mentioned in the previous section) are common interventions. Their singular problem is the lack of empirical evidence meeting the normal standards of scientific evidence that these interventions reduce the risk of child maltreatment and keep children safe.

While there are many documents about evidence-based practice in child welfare,[17] very few interventions are truly evidencebased. Among the most widely discussed, evaluated, and effective interventions are MultiSystemic Therapy (MST) and Triple P (Positive Parenting Program).

One takeaway from a review of evaluated as well as unevaluated interventions and prevention programs is that the focus is primarily on the impact of the intervention on the parent or caregiver. Few of the interventions are designed for or test for the impact of the evaluation on the safety and well-being of children. Again, the parent-as-client bias pervades the development of tools for intervention and prevention (with the nearly unique exception of Nurse-Family Partnerships). The implicit assumption for the interventions and evaluations is that if an evaluation allows a child to remain with his or her birth parents, the intervention is a success. Safety and well-being, and even achieving developmental potential, become subordinate goals.

Over the past decade, the child welfare field has endeavored to develop effective, evidence-based practices. Progress is slow, as would be expected, given the time it takes to develop, test, and replicate random clinical trials. But it is still fair to say that an evidence-based toolbox for child welfare practitioners is relatively sparse.

The scarcity of good tools is partially due to the time it takes to develop them. But it is also related to the resources available for development and testing.

The “Insufficient Funding” Red Herring

Without question, the first and most consistent “suspect” rounded up to explain a child welfare agency’s or system’s inability to protect children is lack of funding. Although numerous funding streams flow into the child welfare system, including Medicaid, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, and Social Service Block Grants, the most substantial funding streams are Title IV-B and Title IV-E of the (amended) Social Security Act of 1935.[18] The Family Preservation and Support Program was added to Title IV-B in 1993. Now called “Promoting Safe and Stable Families,” this provision of Title IV-B is the most recent source of funding for child welfare interventions. According to the U.S. Children’s Bureau:

The primary goals of Promoting Safe and Stable Families (PSSF) are to prevent the unnecessary separation of children from their families, improve the quality of care and services to children and their families, and ensure permanency for children by reuniting them with their parents, by adoption or by another permanent living arrangement. States are to spend most of the funding for services that address: family support, family preservation, time-limited family reunification and adoption promotion and support.[19]

A total of $381.3 million was allocated to the states in fiscal year 2016 in the form of block grants.

The second significant source of federal funding—and by far, the most substantial—is Title IV-E of the Social Security Act. Title IV-E, created in 1980, is targeted exclusively for the costs of placing children into foster care, administering agencies that place and supervise children, and training the workforce that manages foster care placements. For fiscal year 2016, a combined $15 billion in state and federal funds were allocated for out-of-home placement (half the funds are federal, and half are state).

So we have more than $15 billion in federal and state funds to deal with the problem of child maltreatment. But only the tiniest amount of funding—less than $500 million—can be used for prevention and treatment, and those funds are based on a parent-as-client model of intervention with reunification and family preservation as core goals. The largest budget is reserved for and strictly limited to supporting children in out-of-home care.

The real problem dogging the U.S. child welfare system is not insufficient funds but insufficient flexibility in how the existing funds may be used. Because many foster family agencies are dependent on the administrative costs provided under Title IV-E, it creates a perverse incentive that punishes foster care agencies for having unfilled foster care beds. No wonder child welfare administrators, even as they complain about insufficient funds, resist changes in Title IV-E funding.

A plausible change could create greater flexibility: the Family First Prevention Services Act failed to pass the U.S. Senate in 2016 and was reintroduced in January as H.R. 253, the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2017.[20] This bill would transform the open-ended entitlement of Title IV-E into a block grant and provide more flexibility in funding for state child welfare agencies. It would also provide funds for evidence-based interventions. Not surprisingly, there is opposition to the bill from parent advocates as well as institutions that would lose funding under the new funding system for Title IV-E.

Is the Child Welfare System Capable of Changing?

I often tell my social-work students who want to work in the child welfare system the standard child welfare joke: “How many social workers does it take to change a lightbulb?” “One, if the lightbulb sincerely wants to be changed.” I first raised the point of this joke 20 years ago.[21] Most of our child welfare interventions would work only for those parents and caregivers who are ready for change. The stark reality is that caregivers who maltreat their children are no more willing to change their behaviors than are smokers, or those who are overweight, or those of us who should use sunscreen but don’t.

Child welfare systems are no more ready and willing to change than their clients. Class action suits, civil tort actions resulting in multimillion-dollar settlements, and pervasive press coverage of tragedies have yet to substantially influence the values and function of child welfare systems. Even changes in the laws have had mostly modest impacts. The Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997[22] did seem to result in an increase in adoptions out of the foster care system (from 37,000 in 1998 to 50,400 in 2014) and a decrease in the average time that children spend in foster care (from 32.5 months in 1998 to 20.8 months in 2014).

The law also had an “aggravated circumstance” provision, which allows states or counties to bypass reasonable efforts to keep families together and go directly to the termination of parental rights if a court determines that aggravated circumstances exist. Examples of aggravated circumstances:

- Abandonment, torture, chronic abuse, and sexual abuse. The parent murdered another child of the parent.

- The parent committed voluntary manslaughter of another child of the parent.

- The parent aided or abetted, attempted, conspired, or solicited to commit such a murder or voluntary manslaughter.

- The parent committed a felony assault that resulted in serious bodily injury to the child or another child of the parent.

- The parental rights of the parent to a sibling of the child were terminated involuntarily.

Unfortunately, the aggravated circumstances provision of the law is rarely applied by child welfare systems.[23]

There is certainly reason to be pessimistic about the American child welfare system. Still, change is possible. The crucial problems are: agreeing on who the proper client of the system should be, how to improve decision making, and eliminating the perverse incentive of current foster care funding. The essential solutions, in my judgment, are to focus on the child as the client, to make the child’s safety and well-being the goal of the system, and to abandon clinical judgment as the basis for critical and life-and-death decisions. An overdue revision of Title IV-E of the Social Security Act will free up billions of dollars for the child welfare system.

In the end, the lightbulb still must sincerely want to be changed: that will remain the challenge for systems that cling to the belief that parents are the most important clients.

Endnotes

- Yoav Gonen, Kirstan Conley, and Danika Fears, “The Gruesome Details of Zymere Perkins’ Abuse—and How ACS Failed Him,” New York Post, Dec. 14, 2016; Nikita Stewart, “Child Welfare Unit Tied to Toddler’s Death Is Understaffed and Poorly Trained, Report Says,” New York Times, Jan. 26, 2017 (Jaden Jordan); Kerry Burke, Rocco Parascandola, and Graham Rayman, “One-YearOld Whose Parents Have Been Accused of Child Abuse Dies on Staten Island,” New York Daily News, Mar. 22, 2017 (Bianca Abdul); and Rocco Parascandola and John Annese, “Baby Gravely Beaten in Bronx Home Repeatedly Visited by ACS Workers,” New York Daily News, Apr. 18, 2017 (Kadiha Marrow).

- Lindsey Bever, “Social Workers Who ‘Failed to Save Boy from Abuse’ Will Face Trial in His Death,” Independent (London), Mar. 28, 2017.

- Richard Gelles, Out of Harm’s Way: Creating an Effective Child Welfare System (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), chap. 2.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., chap. 3.

- National Commission on Children, Beyond Rhetoric: A New American Agenda for Children and Families (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1991), p. 293.

- 95 Stat. 500, Public Law 96-272.

- See Richard Wexler, Wounded Innocents: The Real Victims of the War Against Child Abuse (New York: Prometheus Books, 1995); and Dorothy E. Roberts, Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare (New York: Basic Books, 2002).

- See Elizabeth Bartholet, “The Racial Disproportionality Movement in Child Welfare: False Facts and Dangerous Directions, Arizona Law Review 51, no. 4 (2009): 871–932; and “Creating a Child-Friendly Child Welfare System: Effective Early Intervention to Prevent Maltreatment and Protect Victimized Children,” Buffalo Law Review 60, no. 5 (2012): 1321–72.

- Bartholet, “The Racial Disproportionality Movement in Child Welfare.”

- Gelles, Out of Harm’s Way, chap. 4.

- Ibid., chap. 5.

- Predictive analytics includes empirical methods (statistical and otherwise) that generate data predictions as well as methods for assessing predictive power. See Galit Shmueli and Otto Koppius, “What Is Predictive About Partial Least Squares?” Sixth Symposium on Statistical Challenges in eCommerce Research (SCECR) (2010).

- For a more complete discussion, see Gelles, Out of Harm’s Way, chap. 5.

- David Olds, “The Nurse–Family Partnership: An Evidence-Based Preventive Intervention,” Infant Mental Health Journal 27, no. 1 (2006): 5–25.

- See Harriet Kitzman et al., “Enduring Effects of Prenatal and Infancy Home Visiting by Nurses on Children: Follow-Up of a Randomized Trial Among Children at Age 12 Years,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 164, no. 5 (2010): 412–18; and John Eckenrode et al., “Long-Term Effects of Prenatal and Infancy Nurse Home Visitation on the Life Course of Youths: 19-Year Follow-Up of a Randomized Trial,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 164, no. 1 (2010): 9–15. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (aka Obamacare) included $1.4 billion in funding for Nurse-Family Partnerships.

- See, e.g., National Association of Public Child Welfare Administrators, Guide for Child Welfare Administrators on Evidence-Based Practice (Washington, D.C.: American Public Human Services Association, 2012).

- PL 74-271.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children & Families, Children’s Bureau, “Promoting Safe and Stable Families: Title IV-B, Subpart 2, of the Social Security Act,” May 17, 2012.

- H.R. 253.

- Richard Gelles, The Book of David: How Preserving Families Can Cost Children’s Lives (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

- PL 105-89.

- Jill Berrick et al., “Reasonable Efforts? Implementation of the Reunification Bypass Provision of ASFA,” Child Welfare 87, no. 3 (2008): 163–82.