“Getting Guns Off the Street”—When It’s Legal to Carry Guns on the Street

Decades ago, carrying a gun—especially a concealed gun—was a reliable indicator of criminal activity in much of the country. Police officers who noticed a civilian “packing” were justified in assuming that the individual was thereby breaking the law; in short, he was an armed criminal. Under a key 1968 Supreme Court decision, this was reason enough to both stop and frisk the suspect.

Things have changed. Over the past several decades, most states have radically liberalized their gun-carrying laws, first by granting concealed-carry permits on a “shall-issue” basis, which means that anyone who meets certain requirements, such as training and a clean background check, is entitled to a permit. Now, more than 20 states no longer require a permit at all. And in June 2022, the Supreme Court, in New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n, Inc. v. Bruen, held that all states must allow law-abiding citizens to carry guns, invalidating New York’s requirement that applicants for a carry license must show a special need to carry, beyond the basic desire for self-defense.

Particularly during a time in which cities across the country have experienced rising gun violence, the court’s decision raises certain issues that need to be resolved. Chief among them: How can police continue to get illegally possessed guns off the street when it is legal—and, indeed, a constitutional right—for many individuals to carry guns on the street?

This report summarizes the legal landscape surrounding stops and frisks. It also investigates—using data from New York City’s stop-and-frisk program—how pedestrian stops of armed individuals tend to play out in practice. The goal here is not to take stances on guns or policing practices. Instead, it is to map out the legal status quo, highlight the tensions among competing priorities, and lay out options that judges and states with different sets of values might consider.

The key conclusions:

- Courts are divided regarding when someone may be stopped on suspicion of carrying a gun, and when a frisk may be conducted on that basis. The Supreme Court should address these splits when presented with an appropriate case.

- There are good ways of balancing the right of law-abiding civilians to carry guns with the need for police officers to stop illegal gun-carrying and protect their own safety. Courts can allow states to structure policies in ways that serve both ends and give states some freedom to pursue their own mix of priorities.

- Americans should not face forcible stops and pat downs merely for exercising their constitutional rights. But states should be allowed, for example, to take a stricter stance toward concealed carry than toward open carry, or to require that guns be carried in an inconspicuous manner and authorize stops of armed individuals whose behavior attracts the attention of officers or other civilians.

- In New York City, the nation’s largest by population, evidence shows that stops that uncover guns are often initiated on suspicion of weapon possession—but they tend to have other bases, in addition—suggesting that changes in the legal landscape need not dismantle efforts to stop illegal gun carriers via street stops.

Introduction

In 1968, the Supreme Court decided Terry v. Ohio, which became a landmark.[1] The case involved a police officer who had observed three men apparently “casing” a business, asked for their names, and—when the men only “mumbled something” in response—patted them down, finding two handguns. The question was whether this was allowed under the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment, which protects Americans’ right to be secure “in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures” and also demands that “no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The court held that, even when police officers lack the probable cause or warrant that would be required for an arrest, they can sometimes stop and frisk suspects based on the lower threshold of “reasonable suspicion.”

A “stop” occurs when someone is detained—when the typical person would understand that he is not free to leave. (Officers generally have the same right as anyone else to initiate voluntary conversations, though courts in New York State have imposed some limitations even on these more casual encounters.)[2] Per Terry, an officer who has a “reasonable suspicion that crime is afoot” may legally stop and question someone to figure out what he’s up to. The issue of “reasonable suspicion,” in turn, is one of the “probabilities”[3] taking into account the totality of the situation, though courts have not explicitly quantified how confident an officer must be before initiating a stop.

A “frisk,” meanwhile, is a brief pat down of the outer clothing for weapons, as distinct from a full search requiring probable cause. Following a stop, a frisk is allowed if the officer has “reason to believe that he is dealing with an armed and dangerous individual.” Frisks are permitted for safety reasons, not to find contraband; but officers are not required to ignore contraband discovered incidentally during these pat downs.

When it was flatly illegal to carry a gun in public, it was easy to see how Terry stops could be central to a mission of “getting guns off the street.” In such a jurisdiction, if an officer reasonably suspects that someone is carrying a gun, by definition he reasonably suspects the subject is an armed criminal, and thus may both stop and frisk the individual. But it’s not flatly illegal to carry guns in public any more. On the contrary, the Supreme Court has affirmed the constitutional right to do so.

Last year, in New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n, Inc. v. Bruen (hereinafter, Bruen),[4] the court built on its earlier rulings in District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008) and McDonald v. City of Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010). Those decisions affirmed, respectively, that the Second Amendment protects the right to keep a gun in the home and that the Fourteenth Amendment applies this protection against state and local governments. In Bruen, the court reiterated its analysis from Heller, indicating that the right to “bear” arms[5] means the right to carry them, and struck down New York’s exacting requirement that civilians demonstrate “good cause” for needing to carry a concealed weapon. Importantly, New York bans open carry, so a concealed-carry permit is the only way to legally carry a gun there.

The state failed, in the court’s view, to identify analogous restrictions from the years surrounding the adoptions of the Second and Fourteenth Amendments. Therefore, the rule was out of step with America’s tradition of firearm regulation, which the court took to delineate the outer limits of regulation permitted by the Constitution.

Bruen still allows states to require training, to limit the places where guns can be carried, and so on. And it leaves in place restrictions prohibiting certain categories of individuals, such as felons, from possessing guns at all.

However, at the intersection of individuals’ right to bear arms and the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable search and seizure, there is an important, and unresolved, question of when a police officer can stop and frisk someone who appears to be carrying a weapon—but might be doing so legally. On the one hand, citizens should not be subject to forcible stops and physical “patting” in sensitive areas of the body merely for exercising their constitutional rights. On the other hand, there is a clear need to enforce the law against illegal gun-carrying, a prime driver of gun violence.

At the level of common sense, there is one obvious consequence of liberalizing gun-carry rules. As those rules loosen, the act of carrying a gun becomes less and less reliable an indicator of criminal activity. It’s a surefire sign of criminality when carrying a gun in public is outright banned and a strong correlate of lawbreaking when permits are extremely difficult to obtain and hardly anyone has one, but an unremarkable behavior when no permit is even required. At least on the margins, then, allowing the legal carrying of guns makes it harder to detect, punish, and deter individuals who carry guns illegally.

To understand this issue at a deeper level, we need to consult the court rulings that have grappled with it directly, as well as ground-level data on how Terry stops work in practice.

Confusion in the Courts

Even before Bruen, Terry stops of gun carriers were the subject of an extensive but low-profile debate in courts and law reviews. Courts sometimes faced cases where either: (a) a legal gun carrier was stopped or frisked and sued to challenge the officer’s conduct; or (b) someone was caught carrying a gun illegally (or found to have other contraband) but argued that the evidence should be suppressed—because, while the officer may have had reasonable suspicion of gun-carrying, he lacked reasonable suspicion that the individual lacked the right to do so legally. Since the mid-2010s, Royce de R. Barondes,[6] Jeffrey Bellin,[7] Shawn E. Fields,[8] Matthew J. Wilkins,[9] Robert Leider,[10] Aaron D. Davidson,[11] Alexander Butwin,[12] J. Richard Broughton,[13] and Kyle Gruca[14] have each compiled and analyzed these developments in law review articles. Several cases raising these issues have been appealed to the Supreme Court; but thus far, the high court has declined to resolve them.[15]

The legal rules governing stops and frisks are not always consistent from place to place. To understand the problems, it is best to go through some relevant court cases. For stops, the key dividing line is whether courts accept the argument that, at least under some states’ laws, concealed carry is a crime and a permit is merely a defense to the crime—something officers need not consider before initiating a stop. For frisks, the key dividing line is how courts read the “armed and dangerous” language from Terry, with some taking the view that a suspect being armed inherently implies danger and justifies a frisk by itself, while others insist that, to initiate a frisk, an officer must reasonably suspect that the suspect is both armed and dangerous.

Stops: “Reasonable Suspicion that Crime Is Afoot”

Years ago, in jurisdictions that banned gun-carrying or made it extremely difficult to do so legally, judges generally (and understandably) found it obvious that reasonable suspicion of gun-carrying is reasonable suspicion of a crime. The prominent federal appeals-court judge Richard Posner put it particularly memorably in the 1996 case U.S. v. DeBerry:

We have assumed—everyone connected with the case has assumed—that the police, who did not know DeBerry’s name and therefore did not know that he was a felon, knew, or at least had reason to believe, that if he was carrying a concealed firearm he was violating the law. They did know. It is a crime in Illinois to carry a concealed gun, with the usual exceptions for peace officers and the like, exceptions unlikely to be applicable to DeBerry.[16]

As Posner also noted, however, the situation would be different in a more permissive state like Texas.[17] (Or, we might add, in Illinois the previous decade, after Posner himself authored a decision invalidating the state’s gun-carrying rules,[18] dutifully applying and extending the Supreme Court’s analysis in Heller despite having publicly disagreed with it.)[19] Even in Texas, cops could have approached the suspect on a voluntary basis to ask if he was carrying a weapon and whether he was a felon. But for an involuntary stop, Posner concluded in DeBerry, “it would be essential that the officers have a reasonable belief and not a mere hunch that if he was carrying a gun he was violating the law.”

That has been the approach of some courts confronting the question in states that allow gun-carrying. In this analysis, to stop someone on suspicion that he is illegally carrying a gun, an officer must reasonably suspect not only that the suspect is carrying but also that he is prohibited from doing so. The Massachusetts high-court case Commonwealth v. Paul R. Couture, from 1990, is an early example. In that case, “the police only knew that a man had been seen in public with a handgun” but had no reason to believe that he lacked a license to carry, and therefore a Terry stop was not justified.[20]

Another common approach, however, relies on the legal concept of an “affirmative defense.” In a criminal court, the burden of proof generally lies with the prosecution: the defense can say nothing at all and still win the case if the prosecution fails to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. However, as the Supreme Court found in 1977’s Patterson v. New York,[21] states may create special defenses for which the burden lies with the defendant. Defendants may be given the burden of asserting such defenses, and of proving them in court by a preponderance of the evidence.

Some courts have applied this concept to stops of concealed carriers, paying special attention to the precise wording of the state statutes governing the issue: Does the law make it illegal to carry a concealed weapon and treat a permit as merely a defense to that crime? Or, instead, is the absence of a permit an element of the crime itself? If the former is the case, some courts reason that an officer shouldn’t have to rule out a potential defense before even initiating a stop. (U.S. v. Gatlin, from the Third Circuit in 2010, is an example.)[22] Sometimes, though, it’s not entirely clear from the statutory text which is even the case.[23]

The element/defense distinction represents the biggest split among courts today, but several other angles to the issue are worth noting as well.

Given that some states require gun carriers to show their licenses to police when asked, the 1979 case of Delaware v. Prouse is relevant.[24] There, the Supreme Court held that police officers may not stop anyone they see driving simply to check his license and registration, a decision with obvious parallels to the concealed-carry context. As Robert Leider has pointed out, Delaware, like most states, had a law requiring drivers to show their license to police if asked.[25]

In the 2017 district-court case U.S. v. Winters,[26] the government pointed to Wisconsin’s statute along these lines as one justification for a stop. The judge handling the case noted that the statute demanded compliance only if an officer acted “with lawful authority” when requesting a permit, making it somewhat unclear if, under the statute, cops could simply demand permits at will from armed civilians. Nevertheless: “Even if Wisconsin wanted to establish the duties and burdens described by the government,” the judge found in rejecting the government’s argument, “it could not contradict the right against unreasonable seizures guaranteed by the United States Constitution.”

The 1980 Supreme Court case Reid v. Georgia, involving two men caught trafficking drugs at an airport, is also germane.[27] A lower court had found the “reasonable suspicion” standard satisfied thanks to the combination of four factors: “(1) the petitioner had arrived from Fort Lauderdale, which the agent testified is a principal place of origin of cocaine sold elsewhere in the country, (2) the petitioner arrived in the early morning, when law enforcement activity is diminished, (3) he and his companion appeared to the agent to be trying to conceal the fact that they were traveling together, and (4) they apparently had no luggage other than their shoulder bags.” The Supreme Court rejected this analysis, in part because the first, second, and fourth circumstances “describe a very large category of presumably innocent travelers.” In other words, the more people do something innocently, the less the behavior will justify a stop.

Additionally, many courts have noted constitutional protections for gun-carrying, which now have become unavoidable under Bruen. Officers can stop people based on behavior that is legal in itself but suggestive of criminal activity, such as the “casing” of a business that was at issue in Terry. But forcibly stopping someone for exercising a constitutional right clearly raises additional concerns. Courts have generally been reluctant, for example, to consider First Amendment–protected bumper stickers as even partial justifications for Terry stops.[28]

Frisks: “Armed and Dangerous”

The frisk question is somewhat thornier than the stop question because a frisk is permitted not to detect illegal activity but to protect the safety of the officer and the public during the stop. Two related issues arise: the precise meaning of “armed and dangerous”; and how a state’s decision to legalize gun-carrying should influence courts’ judgment of which carriers are dangerous.

Confusion over the meaning of “armed and dangerous” can be traced to Terry itself. A literal reading of the term would suggest that frisks are allowed only if both criteria are satisfied. But the Supreme Court was wildly inconsistent in how it restated the standard, sometimes suggesting that “armed” implies “dangerous”—which would mean that the words “and dangerous” in the main formulation are simply redundant, or perhaps that “armed and dangerous” is a “unitary” three-word term whose meaning is, confusingly, identical to that of simply “armed.”

The majority in Terry supported an officer’s ability to frisk when the cop reasonably believes “that the individual whose suspicious behavior he is investigating at close range is armed and presently dangerous to the officer or to others”—and, in another passage, “where he has reason to believe that he is dealing with an armed and dangerous individual.” In yet another passage, however, the majority contended that a “reasonably prudent man would have been warranted in believing petitioner was armed and thus presented a threat to the officer’s safety while he was investigating his suspicious behavior” (emphases added throughout). Similarly, Pennsylvania v. Mimms (1977), addressing a frisk during a traffic stop, summarized the Terry rule as justifying frisks when an officer has “reasonably concluded that the person whom he had legitimately stopped might be armed and presently dangerous,” but then argued that “the bulge in the jacket permitted the officer to conclude that Mimms was armed and thus posed a serious and present danger to the safety of the officer”[29] (emphases added throughout).

Between those cases, 1972’s Adams v. Williams also restated the standard in a vague way, directly acknowledging the possibility that a gun may be legally carried but also reiterating the “armed and dangerous” verbiage:

The purpose of this limited search is not to discover evidence of crime, but to allow the officer to pursue his investigation without fear of violence, and thus the frisk for weapons might be equally necessary and reasonable, whether or not carrying a concealed weapon violated any applicable state law. So long as the officer is entitled to make a forcible stop, and has reason to believe that the suspect is armed and dangerous, he may conduct a weapons search limited in scope to this protective purpose.[30]

The context in Adams is also important. In this case, an informant had said that the suspect possessed both a gun and unspecified narcotics. A police officer asked the suspect to step out of the car, but the man rolled his window down instead; the officer reached into the suspect’s car and found a gun on the suspect’s waistband, where the informant had said it would be. Following an arrest for the gun, a full search produced another gun and some heroin. As the majority put it, finding the handgun right where the informant had suggested “tended to corroborate the reliability of the informant’s further report of narcotics and, together with the surrounding circumstances, certainly suggested no lawful explanation for possession of the gun.” It’s quite different from a situation where an officer reasonably believes that someone is armed but has no reason, separate from that, to suspect that the person is dangerous.

The vague language from the majority is all the more frustrating because two dissents from Thurgood Marshall and William O. Douglas—each wrote one and joined the other’s—stressed that carrying guns and certain narcotics could be legal (with, respectively, a permit or a prescription), and further emphasized that “armed” does not necessarily imply “dangerous.” Presumably, tips to police combining guns and “narcotics” rarely refer to someone with a carry permit and a prescription for hydrocodone. Nonetheless, despite this prodding, the majority missed a chance to clarify the armed-and-dangerous standard.

Yet again, the 1983 traffic-stop case Michigan v. Long,[31] dealing with the search of a glove compartment easily accessible to the suspect, has language that cuts multiple ways. One passage okays such a search when cops reasonably think that “the suspect is dangerous and the suspect may gain immediate control of weapons” (emphasis added), with a separate independent clause for each criterion; another describes the officers in the case as having “reason to believe that the vehicle contained weapons potentially dangerous to the officers”; another contends that “the balancing required by Terry clearly weighs in favor of allowing the police to conduct an area search of the passenger compartment to uncover weapons, as long as they possess an articulable and objectively reasonable belief that the suspect is potentially dangerous”—which would seem to equate the dangerous part of “armed and dangerous” with the whole, as opposed to the armed part.

This confusion has led different courts to take different approaches in more recent cases, especially as law-abiding citizens have become more likely to carry guns. In some places, the state and federal courts with jurisdiction have reached opposite conclusions, meaning that frisks may or may not be invalidated, depending on which level of government handles a case.[32]

To take one much-discussed example, in U.S. v. Robinson—a case notable for how many different opinions it generated from the judges who handled it at various stages of the process, culminating in en banc review[33]—the Fourth Circuit stressed the Supreme Court’s “armed and therefore dangerous”–style phrasings: when conducting a legal traffic stop (which was conceded by all parties in the case at hand), police may frisk a suspect they reasonably think is armed, without regard as to whether the individual might have a permit and without a separate reason to worry that he poses a danger. “[G]iven Robinson’s concessions—that he was lawfully stopped,” the majority wrote—in a passage implying that its logic would extend to pedestrian stops as well—“and that the police officers had reasonable suspicion to believe that he was armed, the officers were, as a matter of law, justified in frisking him.”[34]

A concurrence in the case took issue with treating “armed and dangerous” as a “unitary” concept and pointed to other circuits that had decided otherwise, such as the Sixth Circuit in 2015’s Northrup v. City of Toledo Police Department.[35] (The law required a showing that the civilian was “armed and dangerous,” that court contended, but all the officer “ever saw was that Northrup was armed—and legally so.”) The concurrence in Robinson argued that someone armed with a firearm should be seen as inherently dangerous anyway, thanks to the unique threat that guns pose.

But a four-judge dissent in Robinson went further: “as behavior once the province of law-breakers becomes commonplace and a matter of legal right, we no longer may take for granted the same correlation between ‘armed’ and ‘dangerous.’ ” In other words, even though a frisk is not meant to uncover illegal behavior per se, the legal status of gun-carrying still must influence the determination of which armed individuals are dangerous and thus eligible to be frisked. “If the police in a public-carry jurisdiction want to target a particular armed citizen for an exploratory frisk,” the dissent added, fleshing out the ramifications of a unitary reading, “then they need do no more than wait and watch for a moving violation, as in this case—or a parking violation . . . or, for the pedestrians among us, a jaywalking infraction, as the government helpfully explained at oral argument—and then make a pretextual stop.

In short, courts have not come to agreement as to how stops or frisks should work in a legal-carry world. But before we turn to the question of how they should resolve these issues, some data from New York City provide a sense of how the stop-and-frisks of gun carriers work in practice.

Why Cops Stop Gun Carriers: What the Evidence from NYC Suggests

With strict gun laws, assertive policing, and courts that allow stops based on reasonable suspicion of weapon-carrying,[36] New York City arguably demonstrates the outer limit of what Terry stops can accomplish in a nation with American-style civil and constitutional gun rights. Fortuitously, it also requires police to fill out forms documenting pedestrian stops and then posts the resulting data online, including information about frisks, arrests, summonses, and uses of force. These data provide us information about hundreds of stops of individuals who turned out to be carrying guns, sprinkled in among millions of stops in total.

New York City used stop-and-frisk aggressively in the years surrounding 2010, reporting more than 685,000 stops in the peak year of 2011—and then abruptly curtailed the practice thereafter, as a court found the practice racially biased and a new mayor took office. By the end of the 2010s, the number was about 10,000. Whatever the merits of the old and new approaches, the transition allows us to see data from two very different policies.

To be clear, these data are far from perfect. Especially before the forms attracted so much legal attention, officers often filled them out haphazardly, didn’t fill them out at all, or even filled them out unnecessarily in an effort to look productive. Dubious, unremarkable, and successful stops can all be missing from the data—dubious ones because the officers deliberately avoided documenting them, unremarkable ones because no one likes filling out paperwork, and successful ones because arrests are also documented on other forms and some officers likely found the stop forms redundant. In addition, the data’s format changed in 2017, with the introduction of a new form and a transition to digital recordkeeping.

With those caveats in mind, it’s useful to tabulate what the stated justifications for stopping armed individuals were. Here is a tour of some of the available variables.

Unfortunately, the data’s “suspected crime” variable is essentially unusable before 2017. (It often says simply “FELONY,” for example, and uses inconsistent codes for specific offenses as well.) In 2017, 2018, and 2019, however, the vast majority of stops that produced guns, 80%–85%, were reportedly initiated on suspicion of criminal weapon possession.

The forms also document why officers suspected someone of a crime. Before 2017, justifications for stops (as distinct from frisks and full searches) were divided between two sections. In the first, officers had to check that they saw or suspected at least one of the following: carrying objects in plain view used in crime (such as a pry bar), fitting the description of a suspect, “casing” a victim or location, acting as a lookout, having a suspicious bulge or object, engaging in a drug transaction, making furtive movements, engaging in a violent crime, wearing clothes or disguises commonly used in crimes, and “other.” A second set of boxes, called “additional circumstances,” gave the further options of witness reports, high-crime area, a time period corresponding to high criminal activity, associating with known criminals, proximity to a crime location, evasive response to questions, avoiding or fleeing the officer, ongoing investigations (such as a string of robberies in the area), immediate signs of criminal activity such as bloodstains, and other.

Limiting the data to stops that found guns, Table 1 shows the percentages of forms that had each of these boxes checked, as well as the percentage of the stops that could be traced to “radio runs” (i.e., when someone called the cops to the location). In all the following tables, the justification percentages sum to more than 100% because officers can check multiple boxes.

Table 1

Recorded Circumstances When NYPD Stopped Individuals with Guns, 2010–16

Perhaps most notably, in most of these cases, the “bulge” checkbox—the clearest indication of gun-carrying identified by a proactive officer—was not marked. When the option was checked, it was overwhelmingly accompanied by other circumstances as well, even excluding the weaker justifications of furtive movements, a high-crime area, and/or a time period when crime frequently happens. The typical number of reasons checked was about four—and five, when the “bulge” option was among the boxes checked.

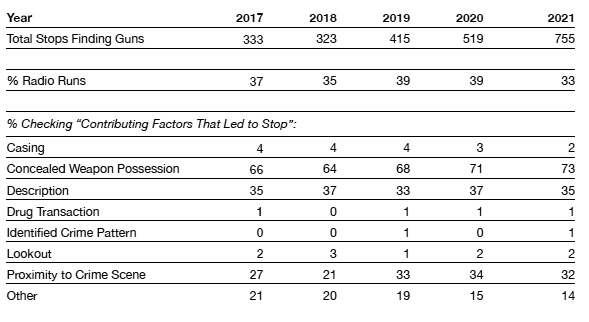

Beginning in 2017 (Table 2), the available checkbox justifications for a stop changed to a more limited set of options (with additional details provided in narratives that are not released with the public data).

Table 2

Recorded Circumstances When NYPD Stopped Individuals with Guns, 2017–21

Just as officers in this period overwhelmingly listed concealed weapon possession as the “suspected crime” in stops where the individual turned out to have a gun, they also checked it as a “contributing factor” for the stop about two-thirds of the time. But about 45% of these concealed-weapon-possession stops involved at least one more reason as well—most commonly, the description and proximity-to-scene options (each appearing in about a quarter of the cases). More than one-third of all stops of armed people had the concealed-weapon box checked by itself—though, given the results from earlier years with more checkboxes available, many officers in these cases presumably could also point to other aspects of the circumstances that seemed suspicious.

Moving on to frisks—allowed under Terry, recall, when a lawfully stopped person may be “armed and dangerous”: before 2017, the available justifications were suspicious bulge, inappropriate attire suggestive of weapon concealment, furtive movements, violent crime suspected, actions indicative of violent crimes, refusal to comply with instructions, knowledge of prior violence by the suspect, verbal threats of violence, and other. In stops of armed individuals where a frisk was conducted (unsurprisingly, the overwhelming majority of stops where officers found guns), the following percentages had these justifications checked (Table 3).

Table 3

Recorded Circumstances When NYPD Frisked Individuals with Guns, 2010–16

Unfortunately, it is not possible to carry this analysis past 2016 because the public data do not include all the frisk-reason checkboxes provided on the new form. Nevertheless, the data generally suggest that the majority of New York’s “gun hit” stop-and-frisks can take place in the future even if officers need to suspect more than simple weapon possession to act. Moreover, the gun stops recorded in the stop-and-frisk data set represent only a fraction of the city’s total gun seizures—which number in the thousands annually[37]—though, as noted above, some successful stops are likely missing from the stop-and-frisk numbers. Roughly 40% of gun seizures come from traffic stops,[38] which are constitutionally easier to initiate because officers have probable cause, not just reasonable suspicion if they directly observe even a minor traffic violation.[39]

Suggestions for Courts

Since courts are not writing on a blank slate, there is no sense relitigating the merits of Terry and Bruen. Instead, the most practical path forward is to focus on reconciling these rulings in a way that balances the need to enforce gun laws with the need to respect the U.S. Constitution.

One conclusion seems inescapable: if carrying a gun is not only legal but a constitutional right, gun-carrying by itself should not subject an individual to a forcible stop by a government agent. But the “affirmative defense” concept that prevails in some courts—in which a state law is interpreted to ban concealed carry while making a permit merely a defense to that crime—may still be viable in certain legal environments: specifically, those where the law applies only to some types of carry (such as concealed carry) while others (such as open carry) remain less restricted.

As mentioned above, there is a long history in the U.S. of permitting open carry while banning concealed carry. Presumably, that regime remains legal. The 2008 Heller decision specifically named concealed-weapons prohibitions as a historically common regulation that courts had upheld; and Bruen, discussing the same laws and court rulings, noted that “concealed-carry prohibitions were constitutional only if they did not similarly prohibit open carry.” If a state can ban concealed carry completely while leaving open carry as a legal alternative, it should also be able to create a less restrictive system wherein open carry is an available option, concealed carry is banned by default, and concealed-carry permits are merely an affirmative defense to that crime. This would give police the ability to stop anyone they noticed was carrying a concealed weapon but could not be said to force stops on anyone who carried at all.

Regarding frisks, there is something to be said for the argument that once an officer has the reasonable suspicion needed for a stop, he should be able to ensure his safety by frisking (and disarming) the armed civilian he’s investigating. After all, regardless of whether the individual might have a permit, he’s already reasonably suspected of criminal activity—and once again, the legal justification for a frisk is safety, not a hunt for contraband.

There is also something to be said, however, for the idea that if carrying a gun is a constitutional right, gun carriers should not face an invasive pat down every time they are stopped for any reason—and they especially should not have officers’ weapons pointed at them in the process, a point that Barondes has emphasized.[40]

One way to draw the line might be to require separate suspicion of “armed” and “dangerous” when stops are initiated solely over minor and routine infractions—so that legal gun carriers aren’t patted down every time they’re pulled over for speeding or a broken taillight—but to allow suspected firearm possession to justify a frisk by itself when officers have reasonable suspicion that something even marginally more worrisome is afoot, so long as it involves a deliberate crime and not, say, an inadvertent violation of a traffic law.

Suggestions for Lawmakers

Much as I accepted the Terry and Bruen decisions as the legal landscape in the previous section, in this section I will start by accepting the fact that different states have different cultures, different population densities, and different attitudes toward guns. The question that remains is: Once a state has decided how strict or liberal its gun laws will be overall, how can it tailor those laws on the margins to help police find the guns that remain illegal?

At the most permissive end of the spectrum—places that allow both concealed and open carry with no permit whatsoever and see unrestricted gun-carrying as a fundamental right of the law-abiding—states should nevertheless be aware that when there are very few legal limits on carrying guns, police will find it somewhat more difficult to identify those who are carrying illegally. Generally, upon realizing that a civilian is carrying a gun, officers will need a good reason to think that the suspect is disqualified (e.g., the officer knows that the suspect has a felony conviction), look for a different rationale for a stop, or settle for a voluntary interaction in which the officer may ask questions but the suspect is free to leave.

For states even slightly more restrictive, a few possibilities arise from the analysis above. One, already alluded to, is that states could consider allowing open carry on relatively lenient terms and making concealed carry a crime, but allow the possession of a concealed-carry permit as an “affirmative defense,” and/or explicitly authorize license checks related to concealed gun-carrying that comes to the attention of police. Presumably, few criminals will want to draw attention to themselves by carrying openly, especially if they have disqualifying criminal records that local police officers may be aware of (or may be motivated to look up).

Would this impose an unfair burden on law-abiding citizens with permits, where they are automatically stopped every time they come within the eyesight of a police officer? In a scenario where widely deployed gun-detecting technology automatically alerts police officers to the presence of concealed guns nearby—perhaps not as futuristic as it sounds[41]—this is a very serious concern. But it’s less of a concern where even a trained police officer is unlikely to notice a properly concealed gun. Arguably, a law-abiding concealed carrier should welcome a brief interaction with a police officer to confirm his permit, because that interaction provides useful feedback that he’s carrying in a way that someone else picked up on.

The distinction between truly concealed carry, and the not-concealed-enough carry that comes to the attention of the authorities, might also serve as a useful tool for lawmakers—regardless of the legal status of open carry, and especially when it comes to indicators more unusual than a “bulge.” In theory, lawmakers could directly legislate on the issue, saying, essentially, that if someone carries concealed, their gun must stay concealed to avoid causing alarm. Legislators could also require best practices, such as the use of holsters (a noted dividing line between legal and illegal carriers). Alternatively or in addition, where laws mandate training and practice to qualify for a permit, police officers could cite clueless behavior as a reason to suspect that a civilian has not been trained and thus does not have a permit.

To set in motion the cases I reviewed in researching this article, gun-carrying civilians did, or were alleged to have done, a lot of unusual things—such as loading a gun in a parking lot and putting it in a pocket before getting into a car,[42] dropping a gun while getting out of a car,[43] leaving a handgun magazine in a basket at a Laundromat,[44] carrying a weapon beneath an unbuttoned suit jacket that exposed the gun to onlookers near a courthouse,[45] showing off a firearm to friends in a pizzeria[46]—even walking in the direction of a school open-carrying an AR-15-style rifle in military apparel a week after the Parkland shooting.[47] When legal gun carriers do such things, they should not be surprised if they end up having a conversation with a police officer and need to show their permit. When illegal gun carriers do such things, they should not be able to get evidence thrown out by claiming that they could have had a permit, for all the cop knew, and therefore the officer had no right to investigate a civilian behaving oddly with a firearm in public.

States can also require legal gun carriers to identify themselves as such in interactions with law enforcement: a “duty-to-inform law,” which many states already have.[48] When such a law applies, an officer’s reasonable suspicion that someone is armed, combined with the individual’s failure to inform the officer that he’s armed upon contact, should equal reasonable suspicion that the individual is carrying illegally, justifying both a stop and a frisk.

Even without such a law, secretive and evasive behavior might contribute to reasonable suspicion. As a majority of Delaware’s high court recently observed, “if a person has a legal right to carry a concealed weapon, that person has no need to act like someone in possession of illegal contraband.”[49]

Conclusion

The half-century-old Terry decision has been on a collision course with legal gun-carrying for decades. Now, with Bruen, gun carrying is not merely legal in many states but a constitutional right for law-abiding citizens in all of them. The Supreme Court should resolve the various circuit splits that this issue has created, and state legislatures and law-enforcement agencies should implement legally sound policies for seizing illicit guns without violating the rights of those who carry them legitimately.

About the Author

Robert VerBruggen is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute, where he provides policy research, writes for City Journal, and contributes to special projects and initiatives in the president’s office. Having held roles as deputy managing editor of National Review, managing editor of The American Conservative, editor at RealClearPolicy, and assistant book editor at the Washington Times, VerBruggen writes on a wide array of issues, including economic policy, public finance, health care, education, family policy, cancel culture, and public safety. VerBruggen was a Phillips Foundation Journalism Fellow in 2009 and a 2005 winner of the Chicago Headline Club Peter Lisagor Award. He holds a BA in journalism and political science from Northwestern University.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).