There is no good news to be found regarding the drug epidemic, judging by a wealth of information recently released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). We now have final drug-death data through 2020, provisional data that reaches through about half of 2021, and a formal report from the agency summarizing trends since 1999.

None of it looks good. Drug deaths have risen almost continuously for more than 20 years, though the mix of substances involved has shifted. Overdoses shot up especially during the pandemic. And where the epidemic was once heavily concentrated among whites, in 2020, the black OD rate actually surpassed the white one.

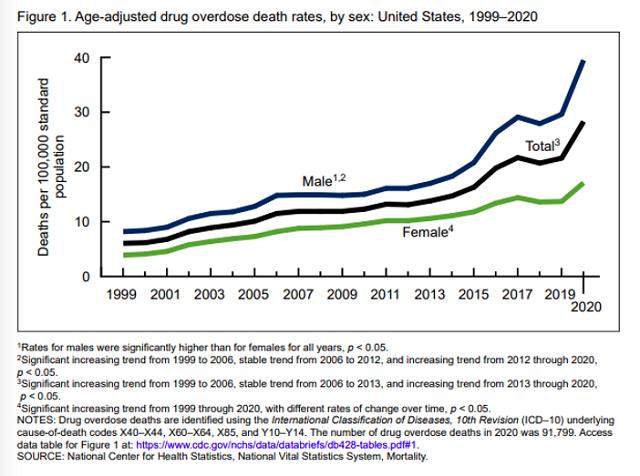

This chart from the CDC report illustrates the scale of the problem. Overdoses slowly but steadily grew for about the first 15 years of the 21st century. They shot up more dramatically for a couple years after that, then stalled, and then lurched upward again in 2020, when the number of fatal overdoses totaled about 90,000. If you randomly picked 100,000 Americans at the beginning of 2020, about 30 of them would have overdosed by the end of the year.

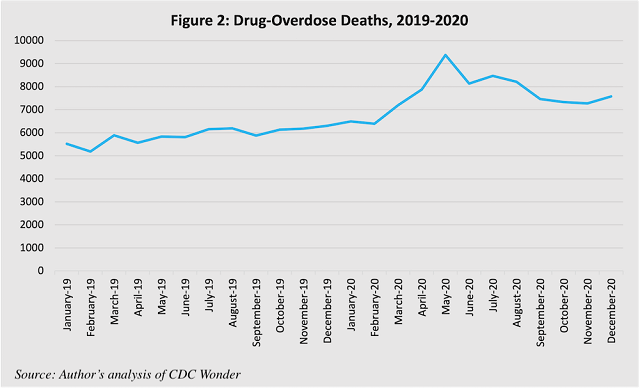

Plotting 2019 and 2020 month-by-month shows that there was an especially dramatic spike in overdoses from March through May of the latter year, during the height of fear and restrictions surrounding the pandemic.

While the abrupt lockdown-era spike did recede, the provisional data through May of 2021 show that a more general increase persisted. The 12-month period ending in May of 2021 is estimated to have about 100,000 drug-overdose deaths; the 12-month period ending in May of 2020—which includes that early-to-mid 2020 spike—had about 82,000.

Combining all drug overdoses this way, however, masks the shifting nature of the epidemic. As the new report details, the epidemic began with prescription opioid pain pills (“natural and semisynthetic opioids” in the formal typology), then transitioned to heroin and then fentanyl (“synthetic opioids other than methadone”). This happened thanks, in part, to changes in policy and the drug supply, including efforts to stamp out prescription-pill abuse. Famously, for example, many users switched to heroin when Oxycontin was made harder to crush in 2010.

Deaths involving some non-opioid drugs, including cocaine and meth, have also shot up over the past five to 10 years, though this is partly thanks to fentanyl being mixed in. 2020 saw nearly 20,000 overdose deaths involving cocaine, and more than 20,000 overdose deaths involving meth and similar psychostimulants.

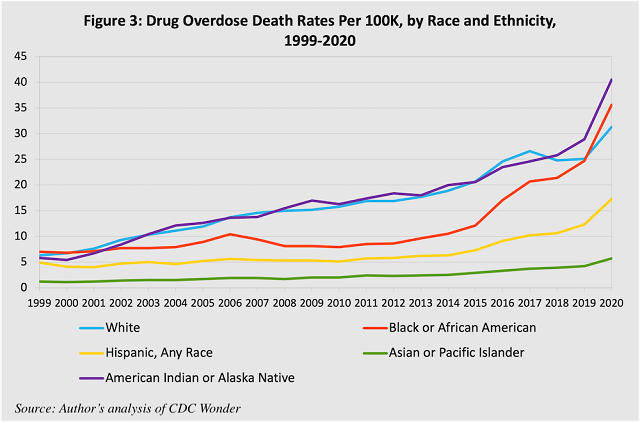

This most recent stage of the drug epidemic has also changed the racial picture. It has long been common knowledge that whites were dying of drug overdoses much more than blacks; go back 10 years, and whites were dying about twice as often, per capita. But in 2020, the gap closed, and the black rate exceeded the white rate for the first time. (The provisional 2021 data suggest this has persisted.) Additionally, while Native Americans have long had similar overdose rates to whites, a gap has opened over the past couple of years (in this chart, Hispanics of all racial identifications are combined into their own category and excluded from all others).

There are some differences between blacks’ and whites’ drug overdoses, as we can see by looking at the substances involved in 2020 deaths (when a death involves more than one type of drug ingested at once, it receives multiple drug-type classifications in the CDC’s system.) For both groups, an outright majority of overdoses in 2020 involved fentanyl or similar synthetic narcotics. But there were gaps for the category including meth (28% of whites’ overdoses vs. 14% for blacks) and cocaine (16% for whites vs. 40% for blacks).

As we’ve discussed frequently here at IFS, race isn’t the only way that drug overdoses have had different effects on different populations. My colleague Kay S. Hymowitz, for example, has explained how opioid deaths are concentrated among single and divorced men, and Charles Fain Lehman has previously discussed whether the pandemic is driving overdoses and other “deaths of despair.”

When drug overdoses fell in 2018, a lot of us got our hopes up that the epidemic was set to implode. A small increase in 2019 dashed that hope. And now, an overdose explosion in 2020, with high numbers continuing into last year, leads to the most depressing conclusion of all: There is simply no reason whatsoever to think things are getting better, or about to get better soon.

This piece originally appeared at Institute for Family Studies

______________________

Robert VerBruggen is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

This piece originally appeared in Institute for Family Studies