Testimony Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

Editor’s note: Oren Cass testifies before the U.S. Senate Banking Committee’s Subcommittee on Economic Policy in a hearing entitled “Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream in Crisis?”

Watch live video on the committee website.

Chairman Cotton, Ranking Member Cortez Masto, and Members of the Committee, thank you for inviting me to participate in today’s hearing.[1]

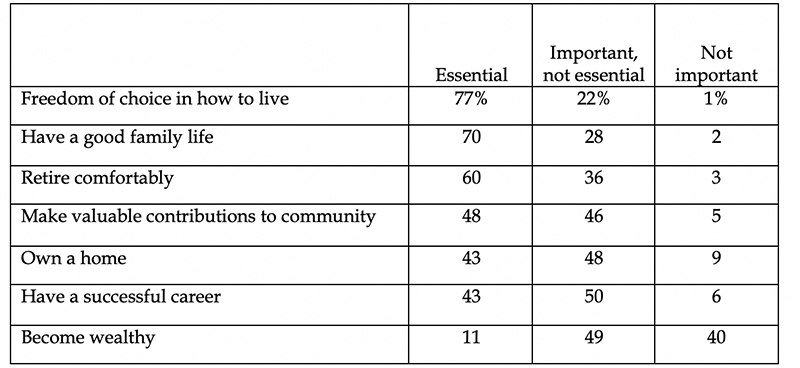

“Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream in Crisis?” is on one hand a critically important topic. Policymaking must orient itself toward clear objectives, and surely the preservation and expansion of the American Dream are among the most important of those. On the other hand, is “economic mobility” what Americans dream of? Not primarily. In 2017, the Pew Research Center studied the question of how Americans define the American Dream and found that economic concerns rank low (see Table 1). By far, the components of life most often deemed essential to achieving the dream were “freedom of choice in how to live” and “have a good family life.” Next came “retire comfortably” and “make valuable contributions to community,” then “own a home” and “have a successful career.” Last, and ranked essential by only one-in-nine respondents, was “become wealthy.”[2]

Table 1: “Do you think each is essential, important but not essential, or not important to your own view of the American dream?”

Source: Pew Research Center

Another poll conducted by Pew in 2014 adds further perspective: 92 percent of Americans said that “financial stability” was more important to them than “moving up the income ladder.” That share actually rose seven points from 2011 to 2014, during a period of economic recovery.[3]

Good economic outcomes are a critical prerequisite to these expressed priorities. Exercising freedom of choice in how to live becomes difficult without the capability to achieve self-sufficiency. Financial stability itself suggests a degree of labor-market success. But in general, the American people appear to have a much richer and more nuanced view of the determinants of their quality of life than do many of their leaders, who have tended to equate prosperity with growth, material living standards, and equality of opportunity on the economic ladder.

This disconnect underscores the importance of precision when discussing economic mobility and opportunity: what exactly do we mean, why do we care, and what should be our goal? My testimony today argues for a greater emphasis on providing all Americans with the genuine opportunity to build a good life rather than on the unachievable ideal of guaranteeing “equal opportunity.” I then highlight our nation’s misguided obsession with higher education as an area ripe for reform.

I. Mobility and Opportunity, Defined

Formally, economic mobility can refer to both absolute and relative concepts. Absolute mobility measures whether the economic conditions of similarly situated people improve from one generation to the next—for instance, how does the median American today compare to the median of twenty or fifty years ago? Are people at age 30 better off than their own parents were at the same age? Relative mobility, by contrast, measures the degree to which people land at different points within the income distribution than did their own parents—for instance, what share of children raised in poor households reaches the top quintile of earners as adults?

Most measures suggest that absolute mobility has declined in America and that the current generation has made less progress than prior ones or even fallen backward. At the end of 2016, Harvard professor Raj Chetty released a landmark study that used millions of tax records to compare parents’ and children’s earnings. For children born in 1950, 79 percent had higher earnings by age thirty than their parents had at the same age. But for those born in 1980, only 50 percent could say the same.[4] Looking ahead to the next generation, only 37 percent of Americans expect that “when children today in our country grow up they will be better off financially than their parents.”[5]

Both measuring and interpreting relative mobility is more complex. While everyone can benefit from high levels of absolute mobility, relative mobility is a zero-sum game: when some people rise within the income distribution, others must fall. Indeed, a high level of relative mobility may not even indicate a prospering society—economic collapse could have a shake-the-snowglobe effect that disconnects people’s relative socioeconomic status from that of their parents, but it would hardly be cause for celebration. Still, the metric remains important because of its implications for fairness and opportunity. A society with no relative mobility would be one in which someone’s station at birth dictated his economic trajectory regardless of his own aptitudes and efforts. High relative mobility suggests that opportunity is widely accessible.

American politics often starts from the presumption that our goal is “equal opportunity” defined as “equality of life chances”—that where a child starts should have no bearing on where he ends up and that everyone should have an equal chance of arriving at any destination.[6] That is plainly impossible in a world in which individuals possess different innate characteristics and grow up in different environments. Perhaps it could be reached by replacing unique individuals with generic clones and diverse family environments with state-run children’s homes. Most people would agree that this is not desirable.

A more pragmatic vision of equal opportunity entails removing any public impediments that obstruct individuals in pursuing their goals. Unfortunately, that may not get us as far as we would like. Consider the findings of the Brookings Institution’s Richard Reeves, who used data from more than five thousand Americans born mostly in the 1980s and 1990s to compare the income quintile in which they were born to the income quintile they later reached. So, for instance, of those born into households with income in the bottom 20 percent of all American households, how many found themselves in the bottom 20 percent as adults?

Family structure dictated opportunity. For someone born in the bottom quintile to a married mother and raised by both parents, the odds of reaching the top quintile were higher (19 percent) than remaining in the bottom quintile (17 percent). Indeed, those children faced almost perfectly equal chances of landing anywhere as adults (between 17 percent and 23 percent in each of the five quintiles). Public impediments appeared to exert little influence. But for someone born in the bottom quintile to a never-married mother, the odds of rising to the top quintile (5 percent) were one-tenth those of remaining in the bottom quintile (50 percent). The private impediment was almost insurmountable.[7]

In the face of dynamics like these, guaranteeing “equal opportunity” would require implementation of public programs capable of counteracting all of life’s disadvantages. American policymakers have come to see education as the panacea capable of accomplishing just that, and so have embarked upon the quixotic quest of “college for all.” This approach has been a mistake whose primary victims are precisely those it is intended to help—people who remain unlikely to emerge successfully from a high-school-to-college-to-career pipeline yet are offered no meaningful alternative (as discussed below in Part II). The sad irony is that, in our effort to deliver “equal opportunity,” we have built an education system that more resembles an impediment to opportunity. If the aspirations of the American people—the American Dream—in fact required an equalization of life chances then perhaps it would be appropriate to continue tilting at windmills in hopes of somehow emerging victorious. Fortunately, they do not.

Rather than measure the American Dream in terms of economic mobility and the number of rags-to-riches stories featured in the news, policymakers should focus on ensuring that every American has access to some minimum, absolute level of opportunity to achieve self-sufficiency, support a family, contribute to a community, and then provide to his children even greater opportunity. Historically, someone who earned the basic level of education widely attainable within society, worked full time, and formed a stable family could reasonably expect to achieve all these things. And he could achieve them either by setting off for a new city or staying right near home.

Measured against such objectives, America faces very serious challenges. Consider how the median income of a man with a high school degree compares to the poverty line for a family of four. In 1970, he could support a family at more than double the poverty line. In 2016, he cleared that threshold by less than 40 percent. In dollar terms, that represents a loss of roughly $20,000 in 2016 earnings; a median of $33,500 instead of $54,200.[8] The U.S. Census Bureau reports that, between 1975 and 2016, the share of men aged twenty-five to thirty-four earning less than $30,000 per year rose from 25 to 41 percent.[9]

Figures like these give us the best indication of how the American Dream is doing in economic terms, and they should worry us deeply. If decades of extraordinary economic growth and technological progress have left them trending downward, a serious reexamination is in order.

II. Implications for Education

U.S. public policy relies almost exclusively on college to prepare young men and women for productive employment. Within the education system, high schools operate primarily as college-prep academies, and waves of reform have focused ever more intensively on “college readiness.” Federal and state subsidies to higher education total more than $150 billion annually.[10] The federal government today spends only $1 billion annually on Career and Technical Education (CTE), and the funds devoted to CTE have been declining steadily in real terms. Since 1990, the share of high school students earning CTE credit, the share of credit-earners qualifying as CTE “concentrators,” and the average number of CTE credits earned per student have all declined as well.[11]

This overwhelming emphasis on college as the path to productive employment is not working. Only one-third of Americans earn a bachelor’s degree by age 25, and that figure has changed little in the past two generations;[12] most Americans still do not attain even a community-college degree.[13] Even among recent college graduates, 41% hold jobs that do not require a degree.[14] All told, fewer than one in five Americans move smoothly from high school to college to career.[15]

One reason for these meager results is that colleges themselves are not designed to play the role of career preparation for the masses. By overwhelming margins, Americans’ top priority for higher education is employment opportunity,[16] but that’s not the role that institutions see for themselves. As Harvard University’s Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz have observed, “The business of colleges and universities is the creation and diffusion of knowledge.”[17] In a 2017 survey by Gallup of more than 700 college and university presidents, only 1% strongly agreed with the statement that “most Americans have an accurate view of the purpose of higher education”; four times as many disagreed as agreed.[18] Nor do most educators have up-to-date experience with relevant technical skills or in industries outside the field of education.

Appropriate pathways for most young people preparing to enter the workforce would focus on technical training coupled with time on the job. This is the approach taken by virtually every developed economy besides the United States. For most developed countries, according to a report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 40%–70% of high school students are enrolled in career pathways that emphasize technical training, often with a significant on-the-job component. The U.S. is excluded from the analysis because of “the rather different approach to vocational education and training in US high schools.”[19] Beyond the education system, the U.S. focuses little public investment on worker training: less than 0.1% and declining as a share of Gross Domestic Product; among the lowest levels in the OECD; and an order of magnitude less than many developed economies.[20]

Effectively reforming the American system requires the implementation of tracking: offering dramatically different programs of secondary education depending on whether the student will proceed next to college or directly to a career. Unfortunately, this also explains why the American system has gone so far astray and reform will be so challenging. Americans have long resisted tracking.

In 1892, Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot exclaimed, “I refuse to believe that the American public intends to have its children sorted before their teens into clerks, watchmakers, lithographers, . . . and so forth, and treated differently in their schools according to their prophecies of their appropriate life careers. Who are we to make these prophecies?”[21] When the nation pioneered universal secondary education in the early twentieth century, its “comprehensive high schools” emphasized a broad education in the liberal arts.[22] During the 1960s and 1970s, in keeping with so many other areas in which idealism trumped practicality at the expense of the purported beneficiaries, the notion of tracking was squelched entirely.[23]

This particular bout of American exceptionalism is a mistake. What sense does it make to treat the vast majority of high schoolers as if they were prospective college graduates when they are not, to pretend that the sudden divergence of outcomes after high school graduation did not in fact begin long before? Indeed, the best way to understand the American system is not as trackless but rather as committed to a single track tailored toward those most likely to succeed anyway.

One common objection to tracking is that a career track will be disproportionately populated by students from disadvantaged backgrounds. But this is a description of society and an implicit condemnation of the current system, not a plausible criticism of tracking. After all, students best suited to a career track are precisely those least well served by its absence and experiencing the worst outcomes today. A tracked system could offer them a better chance at economic success, increasing in turn the odds that their own kids land on the college track a generation later. It will speed social progress and improve countless lives along the way.

A tracked system also will unavoidably place some students on a career track who might have done well in college. But the career track is not a death sentence. It can lead in many cases to a more fulfilling (and even more remunerative) career than might the college track, especially for its most talented students. And individuals would have opportunities to shift tracks both during their education and much later; as the New York Times notes, “it is not uncommon to find executives in Europe who got their start in apprenticeships.”[24] No public education system will serve every student well, but the share finding themselves mismatched will be far lower if programs at least try to meet the needs of the majority.

Society must choose between proceeding with a charade and acknowledging honestly the limitations it faces. Pretending against all evidence that every student should prepare for college sustains the fiction that government programs can compensate for various background disadvantages and thus deliver “equal opportunity,” defined as equality of life chances. Pushing every student in that direction yields the occasional Horatio Alger story, which warms the heart and stands for the proposition that the same could happen to anyone, even though its rarity in fact underscores the opposite. The approach is most useful to those least affected by it, who benefit from innate and environmental advantages, who can flourish in college, and who can now justify a broad array of economic policies that further benefit themselves by claiming that everyone else can follow their path too. It is most harmful to those already disadvantaged, who must now navigate a system that has proven repeatedly its inability to meet their needs.

The Workforce-Training Grant

The federal government should take aggressive policy action to facilitate the creation of attractive noncollege pathways and channel investment toward people traveling along them. Effective reforms will recognize that, while society has a strong interest in supporting young people as they move from high school toward adulthood and the work force, universities are not necessarily the institutions best suited to provide that support. In many cases, the best providers will be employers. Here I propose a specific policy, the Workforce-Training Grant, which would place employers on equal footing with universities by creating an open-ended government stipend attached to eligible private-sector workers and payable to any employer placing a worker in a program of combined on-the-job experience and formal skill development.

The grant should be structured as a per-worker payment that employers receive for employing someone under the conditions defined as workforce training. Other programs exist that provide tax credits for the employment of particular classes of workers (e.g., the Work Opportunity Tax Credit[25] and the proposed ELEVATE Act[26]). But these programs typically target narrow groups with specific formulas. The better approach is to define broadly the circumstances of someone who is employed while in training and designate that person as a “trainee,” essentially the equivalent of a “student” as we recognize someone enrolled in college.

For example: a trainee might be defined as any person who is employed at least 15 hours per week and also engaged in a certified training program for at least 15 hours per week—regardless of the trainee’s personal characteristics and regardless of where the training program is provided. This would place employers in control of offering the jobs and related training, while leaving workers in control of what program/employment they want to accept. Just like federal subsidies for college, the funding is attached to the trainee but flows through the provider (in this case, provider of employment).

An employer would receive a $10,000 per-year payment (prorated) for employing a trainee, disbursed directly to the employer, just as traditional tuition loans and grants are paid directly to schools. Employers would have to initially register employees as program participants, with verification from employees themselves of their trainee status, after which that status would be tied directly to the tax identification data through which payroll and other taxes are reported and withheld each pay period. As a condition of program participation, employers could be required to participate in a reporting program that tracks the employment status and long-term earnings of employees who begin as trainees.

Employers could potentially even employ trainees for “free” but would want to do so only if they saw the trainees as adding some value to the business. (The grant would be sufficient to pay the worker $13 per hour for 15 hours per week, though the employer would still need to provide a training program or pay the cost of attendance at a third-party program.) An employer could hire trainees and receive the grant only if their employment/training offer were the one most attractive to the trainee—if some other firm wanted to offer better training, or a higher wage, or a more attractive career path, the trainee could go there instead.

In many cases, community colleges might provide the site for training. Critically, though, colleges could no longer attract public funding only by enrolling a student—rather, their customers would now also include employers, and their success would depend on offering programs that appeal to employers’ needs. The employer would likewise have a greater incentive to engage with the community college in designing a relevant and integrated program of study. In other cases, employers might operate training programs themselves or through industry associations or union partnerships.

A grant of this nature would scale gradually, as more programs gain certification. It also lends itself to initial pilots, particularly states or metropolitan areas, and potentially with caps on total enrollment. Opportunity Zones, which have already been identified by states as areas of high need and which, in many cases, have leaders actively seeking opportunities to build public-private partnerships that can attract and take advantage of new investment, might make particularly attractive targets for initial pilots. In June 2019, the U.S. Department of Labor proposed a positive step: a rule to allow entities like trade associations, unions, and colleges to define the parameters of industry-recognized apprenticeships that would be eligible for state and federal funding.[27]

Funding for the Workforce-Training Grant should be redirected from within the existing $150 billion spent by federal and state governments on higher education each year. The allocation should shift gradually and predictably: if half this total were shifted over 10 years (roughly a $7 billion cut to college and a $7 billion increase to noncollege each year), colleges and their students would have time to adjust while states, districts, community colleges, and employers would have to plan for standing up alternatives. While the federal government can shift only a portion of higher-education funding itself, states should be allowed to supplement the Workforce-Training Grant’s value with their own funding.

Both the new funding for employers and the transfer of funding from the higher-education system are necessary for a more effective system. As noted, community colleges may ultimately play an active role in this new system, but their attention must turn from enrolling students directly toward partnering with employers. One source of funding will need to decline alongside the other’s increase if a significant change in behavior is to occur.

Conclusion

A rebalancing is in order. Shifting funding from colleges and universities to employers may appear unappealing at first, but it is best understood as a reallocation from one training provider to another. All are entities that might hypothetically equip less educated workers with valuable skills that will accrue to their own benefit in the form of higher wages. None will do so for free. Of the providers, available evidence suggests that the latter (employers) can do a better job than the former (colleges); to pay only the former is backward in principle and has yielded poor outcomes in practice.

Thank you again for the opportunity to testify on this important topic.

Endnotes:

[1]Portions of this testimony are adapted from Oren Cass, The Once and Future Worker: A Vision for the Renewal of Work in America (New York: Encounter Books, 2018); and Oren Cass, “The Workforce-Training Grant,” Manhattan Institute, July 2019.

[2] Samantha Smith, “Most Think the ‘American Dream’ Is Within Reach for Them,” Pew Research Center, October 31, 2017.

[3] “Americans’ Financial Security: Perception and Reality” (Issue Brief, Pew Charitable Trusts, Philadelphia, March 2015).

[4] Raj Chetty et al., “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility since 1940” (Working Paper 22910, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Mass., December 2016).

[5] Bruce Stokes, Global Publics More Upbeat about the Economy: But Many Are Pessimistic about Children’s Future (Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, June 2017).

[6] David Azerrad, “How Equal Should Opportunities Be?,” National Affairs, Summer 2016.

[7] Richard V. Reeves, “Saving Horatio Alger: Equality, Opportunity and the American Dream” (Brookings Essay, Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., August 20, 2014).

[8] “Historical Income Tables: People,” U.S. Census Bureau, tables P-16 and P-17; “Poverty Thresholds,” U.S. Census Bureau.

[9] Jonathan Vespa, The Changing Economics and Demographics of Young Adulthood: 1975–2016 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, April 2017).

[10] Oren Cass, “How the Other Half Learns,” Manhattan Institute, August 2018. This total includes state university systems and state tuition aid, federal Pell Grants and loan subsidies, and tax benefits.

[11] U.S. Department of Education, “National Assessment of Career and Technical Education: Final Report to Congress,” September 2014.

[12] David J. Deming, “Increasing College Completion with a Federal Higher Education Matching Grant,” Brookings Institution, Hamilton Project, April 2017.

[13] National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics 2018, February 2019, table 104.30.

[14] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates, “Underemployment Rates for College Graduates,” May 2019.

[15] Cass, “How the Other Half Learns.”

[16] Rachel Fishman, “Deciding to Go to College,” New America Foundation, May 2015.

[17] Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, “The Shaping of Higher Education: The Formative Years in the United States, 1890 to 1940,” Journal of Economic Prspectives 13, no. 1 (Winter 1999): 38.

[18] Scott Jaschik and Doug Lederman, eds., “2017 Survey of College and University Presidents,” Inside Higher Ed and Gallup, 2017.

[19] Learning for Jobs (Paris: OECD, 2010).

[20] “Public Spending on Labour Markets: Training (2000–2016),” OECD Data, 2019; see also “Labor Market Training Expenditures as Percent of GDP in OECD Countries, 2011,” Brookings Institution, Hamilton Project, June 2014; “Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and the Economy,” Executive Office of the President, December 2016.

[21] Sandra Salmans, “The Tracking Controversy,” New York Times, April 10, 1988.

[22] Paul Beston, “When High Schools Shaped America’s Destiny,” City Journal, 2017.

[23] Tom Loveless, How Well Are American Students Learning? (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, March 2013).

[24] Jeffrey J. Selingo, “Blue Collar Redefined,” New York Times, February 5, 2017.

[25] “Work Opportunity Tax Credit,” Internal Revenue Service, April 2019.

[26] “Wyden and Davis Introduce Legislation to Bring More Americans into the Workforce, Reduce Barriers to Employment,” U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, news release, January 15, 2019.

[27] Eric Morath, “Trump Administration Proposes New Type of Apprenticeship,” Wall Street Journal, June 24, 2019.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).