Testimony Before the U.S. House Ways & Means Subcommittee on Oversight

Chris Pope testified virtually before the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee’s Oversight Subcommittee on the state of the Affordable Care Act in a hearing entitled “Maximizing Health Coverage Enrollment Amidst Administration Sabotage.”

Chairman Pascrell and Ranking Member Kelly,

Thank you for the opportunity to appear before the Ways and Means Oversight subcommittee hearing on expanding health insurance coverage to more Americans.

As the American people prepare to head to the polls, the committee is doing them an important service by taking time to review the arguments for reforms made over the past four years, the claims made against them, and the evidence regarding how they have worked out.

My testimony begins with an assessment of the good and bad consequences of the Affordable Care Act’s various reforms to non-group health insurance markets. It considers the aspects of the legislation that most urgently needed fixing: the inequitable and ineffective individual mandate penalty, and restrictions on insurance plans that offer lower premiums to individuals who sign up before they get sick. I assess the effects of policy changes to remedy these problems, and conclude by discussing future reforms to fix flaws that still remain.

Problems that needed fixing

Prior to the Affordable Care Act, 49 million Americans lacked health insurance coverage, while an estimated 18% of applications for insurance were denied due to pre-existing conditions.[1] The Affordable Care Act rightly sought to address this situation by making funds available to subsidize the provision of health insurance.

However, the ACA did not simply target a subsidy at Americans who were uninsurable or unable to afford insurance coverage at actuarially fair rates. Instead, the legislation required insurers to price plans the same for people who signed up before they got sick, as for enrollees who have major pre-existing medical conditions. This made it rational for many people to wait until they got seriously ill before purchasing insurance from the individual market.

As a result, the average medical needs of those enrolled in plans began to soar as the ACA’s insurance market reforms were implemented in 2014. This forced plans to drive premiums higher, hike deductibles, and cut access to providers most appealing to the seriously ill, in order to stay in business. Average premiums on the individual market rose by 105% from 2013 to 2017.[2] By 2018, premiums for family coverage on the individual market averaged $14,016 in addition to deductibles averaging $8,803 – which is to say enrollees were required to pay $22,819 before insurance coverage kicks in.[3]

By the fall of 2016, many insurers had dropped out of the marketplace altogether, leaving 1,036 of the 3,007 counties in the nation with only a single insurer on the individual market.[4] Whereas the median county had 7 competing insurers offering Medicare Advantage plans in 2019, it had only 2 competing insurers on the ACA’s individual market.[5]

As a self-financing competitive insurance market that offers value enrollees are willing to pay for, the ACA’s individual market has essentially collapsed. But the presence of subsidies, which expand as necessary to guarantee a defined benefit to low and middle-income Americans, have prevented it from entirely succumbing to a death spiral. Those subsidies, along with the Medicaid expansion, entirely account for the ACA’s modest coverage gains.[6] Without subsidized enrollees and federal overpayments for subsidized healthy enrollees, which indirectly cross-subsidize the nominally unsubsidized, it has been estimated that individual market enrollment would fall by 80%.[7]

As 8.6 million of 12.5 million enrolled in individual market plans receive subsidies that automatically expand to guarantee a defined medical benefit at premiums limited as a share of income, ACA plans ought therefore to be understood as an entitlement in disguise. An accessible source of insurance, which offers good value for Americans to purchase before they get sick, needed to be re-established.

The benefit of recent reforms

Short-Term Limited Duration Insurance

Short-Term Limited Duration Insurance (STLDI) was specifically exempted from the ACA’s insurance pricing reforms, and therefore remained the only form of insurance for which individuals could receive lower premiums in return for signing up before they get sick. The Obama administration in 2016 sought to limit the duration of STLDI plans to 90 days and to prohibit its renewability. In April 2017, I proposed that the Trump administration overturn this rule, which it did from the end of 2018.[8] STLDI coverage is now available for up to a year and can be renewed for up to 3 years – unless restricted by state law.

Premiums for STLDI plans are consistently lower than those for ACA plans that offer equivalent benefits and coverage of medical costs, and in some cases are available at half the price. Because ACA regulations effectively impose a tax on the purchase of insurance by people who sign up before they get sick, the savings to be gained from switching to STLDI plans are greater for the purchase of more comprehensive insurance coverage.[9] Whereas “platinum” ACA plans covering 90% of medical expenses were entirely unavailable in 35 states, STLDI plans covering 100% of hospital and physician costs beyond a $2,500 deductible are now widely available where permitted by state law.[10]

Where permitted, STLDI plans are available covering not just hospital and physician services, but mental health, substance abuse, and prescription drugs – with more insurers typically competing than in ACA markets.[11] Insurance coverage of maternity services is harder to provide on an actuarially fair short-run basis, though Blue Cross of Idaho does so by setting deductibles so that plans effectively provide insurance against complications.[12] The Idaho plans also use waiting periods to allow individuals with pre-existing chronic conditions to receive underwritten coverage for less than ACA premiums.[13]

As ACA plans that offer the highest rated hospitals tend to get overwhelmed by an influx of patients who first purchase coverage when they are seriously ill, so most are now structured as HMOs and pay for only the bare minimum network of in-state hospitals that they are specifically required to cover by law.[14] By contrast, the most popular STLDI plan has a broad national PPO network that provides access to the highest rated national facilities such as the Cleveland Clinic, Sloan Kettering, the Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins, and Mass General.[15]

Satisfaction rates of STLDI plan enrollees (91%) are significantly higher than those in ACA plans (70%).[16] The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that 95% of those shifting from ACA to STLDI coverage will do so in search of comprehensive benefits, rather than so-called “skinny plans.”[17] A survey of individuals purchasing coverage online found 43% of those purchasing STLDI plans would otherwise have gone altogether uninsured, while only 22% would have purchased ACA plans.[18]

Direct subsidies

As they expand automatically as necessary to guarantee a defined benefit of coverage to would-be enrollees at a limited share of income, the subsidies are the most important element of the ACA’s protections for individuals with pre-existing conditions. If one understands ACA plans as a safety-net entitlement, rather than as a perfect insurance plan that everyone must be coerced into purchasing, recent policy by the Department of Health and Human Services has been supportive and well-focused.

Although silver-loading is no-one’s idea of an optimal method for allocating subsidies, the current administration has done nothing to prevent states and plans from receiving the necessary assistance.[19] Furthermore, they have approved reinsurance waivers that have increased subsidies for ACA plans in Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin.[20]

Mandate Repeal

The individual mandate was initially advocated as an attempt to mitigate the incentive that the ACA created for individuals to wait until they get seriously ill before signing up for coverage.[21] Yet, it was never politically possible to implement a mandate that fulfilled this theoretical function, because the associated penalty was inherently inequitable.[22]

As most middle and upper-income Americans have employer-sponsored insurance, the mandate’s penalty largely hit low-income Americans or those who had just lost their job – neither of which had much ability to pay astronomic sums for threadbare coverage. In 2016, the Obama administration therefore exempted 23 million of the 30 million uninsured from the mandate, while only 1.2 million earning above the subsidy cut-off were subject to a penalty exceeding $1,000.[23] With few low-risk people willing to pay over $14,000 for family plans that offer merely catastrophic coverage, individual market enrollment among those ineligible for subsidies collapsed from 9.4m in 2014 to 5.2m in 2018 – even before the mandate was eliminated.[24]

Even if a stronger mandate could improve the overall risk pool, it would likely not necessarily yield lower premiums, as mandating the purchase of insurance also strengthens the power of insurers to inflate their markups.[25] Indeed, a stronger mandate would likely only exacerbate the problem of adverse selection between insurance options by driving low-risk individuals to purchase skimpy plans.[26] Nor, given the existence of subsidies that expand to guarantee the provision of ACA plans as a defined benefit safety-net, is such a mandate necessary.

Individual Coverage HRA rule

The Individual Coverage HRA rule may prove to be the most significant health policy reform implemented over recent years.[27] This is because it tackles the primary root cause of the risk that people will be denied coverage due to pre-existing conditions: the prospect that they will be forced to seek new insurance, while already sick, due to a change in employment circumstances.

The individual market has long been a fragile residual market, which people enter and leave between sources of employer-sponsored coverage. Only 47% of enrollees remain enrolled in individual market plans for more than a year, and only 30% do so for two years or more.[28] By extending the tax exemption of employer-sponsored health insurance to coverage that individuals purchase for themselves, the ICHRA rule allows individuals to maintain the same guaranteed-renewable insurance plans across jobs – eliminating the risk that they will be denied coverage due to pre-existing conditions when their employment circumstances change.

By extending the tax exemption of health insurance to plans purchased from the individual market, the ICHRA rule also allows employees to control the benefit packages, cost-sharing levels, and provider networks in which they are enrolled. A recent study of healthcare choices estimated that staff would be willing to give up 10% to 40% of subsidies they receive from employers in order to choose a plan that better suit their needs and preferences.[29]

Predicted harm didn’t occur

When Congress contemplated the repeal of the individual mandate and allowing individuals to purchase non-ACA plans, opponents predicted that doing so would cause the ACA market to fall apart.[30] In a publication for the Center for American Progress, economist Jonathan Gruber of MIT estimated that repeal of the individual mandate would cause average individual market premiums to rise by 40% and 22 million fewer Americans to have health insurance.[31] These claims seemed far-fetched to me and others at the time.[32]

The Census Bureau recently released its findings from two surveys of health insurance coverage in 2019 – the first year for which the individual mandate had been eliminated. Its “American Community Survey” estimated that only 1.1 million more Americans were uninsured in 2019 than in 2018, while its “Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement” found that the number of Americans without health insurance coverage actually declined by 1.4 million in the year following the mandate’s repeal.[33]

Warnings of doom associated with the deregulation and expansion of STLDI coverage have proved similarly unfounded. In 2017, the Commonwealth Fund suggested that STLDI plans would “syphon healthy individuals away from traditional health insurance, resulting in a sicker risk pool in the individual market, driving up premiums, and putting the individual insurance market at risk.”[34] The Center for American Progress called the expansion of STLDI plans “sabotage.”[35]

Yet, in a Kaiser Family Foundation survey of ACA plans requesting rate increases for the 2019 plan year (the first in which they would face competition from STLDI plans), 92 of 124 insurers failed to mention STLDI deregulation as a significant factor leading them to raise rates, while the median rate increase among those who attributed any cost to competition from STLDI plans was less than 1%.[36] The Congressional Budget Office in 2019 therefore estimated that a House bill to reimpose a 3-month limit on STLDI plans would throw 1.5 million Americans off their preferred insurance every year, while only reducing unsubsidized ACA premiums by 1%.[37]

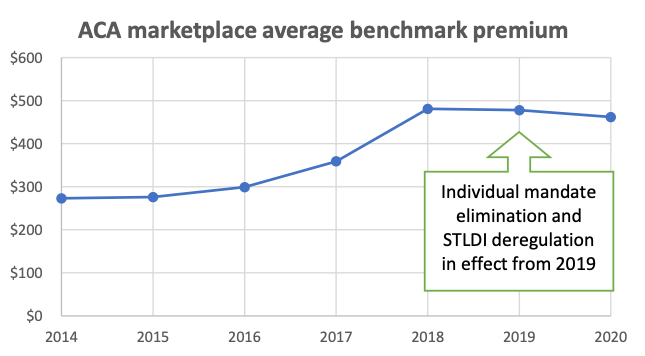

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation[38]

The 2019 elimination of the individual mandate and expansion of STLDI plans has had little impact on the ACA’s risk pool, the profitability of plans, or premium levels.[39] Whereas ACA premiums soared by 105% in the four years following the establishment of the ACA’s regulatory reforms to the individual market, premiums have fallen by 4% in the two years since the individual market has been repealed and STLDI plan term expanded.[40] On average, ACA premium increases for 2019 were in fact most substantial in states that banned the renewal of STLDI plans (7.3%) or those that prohibited them entirely (+6.7%), whereas ACA premiums actually declined on average in states that merely restricted STLDI terms to less than a year (-1.7%) or allowed them fully according to federal rules (-0.2%).[41]

The number of unsubsidized individuals enrolled in nongroup ACA plans declined by 20.4% from 2016 to 2017, and 24.4% from 2017 to 2018, but only by 8.6% from 2018 to 2019 in the year the individual mandate was repealed and STLDI deregulation implemented. In fact, the decline in enrollment was exactly the same in the 16 states that allowed STLDI to the full extent permitted by federal law (8.6%) as where STLDI plans were restricted by state law (8.6%)[42]

Going forward

The Affordable Care Act was enacted more than 10 years ago. Like most other pieces of significant legislation over a similar time frame, it has since changed enormously – often as the result of bipartisan legislation.

· Title I, relating to insurance market regulation, has seen the repeal of the individual mandate, expansion of alternatives to exchange plans, and restructuring of CSR subsidies.

· Title II, relating to Medicaid, has seen some states embrace the expansion as originally intended, others opt against expansion, and a third set adopt various forms of partial expansion.

· Title III, relating to Medicare, has to a large extent been revised by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

· Titles IV to VII, relating to various medical delivery issues, have similarly been superseded by subsequent laws, such as the 21st Century Cures Act.

· Title VIII, establishing a Long-Term Care entitlement, has been repealed altogether.

· Title IX, relating to revenue provisions, has seen many of its largest elements, such as the Cadillac Tax, Medical Device Tax, and Health Insurance Tax, eliminated.

What remains of the ACA now forms part of the complex and tangled fabric of American health policy, along with many other similar pieces of legislation and dozens of budget agreements that have been enacted over the years. That being the case, every year it makes less sense to discuss health policy through the lens of all-or-nothing attitudes to a sweeping and divisive 10-year-old piece of legislation. Rather, it is better to discuss fixing insurance markets in ways that transcend uncritical support or indiscriminate opposition to the ACA. Doing so would enable policymakers to build on what is good from the legislation, while jettisoning what is bad.

While subsidized ACA plans are important as a safety-net for low income individuals and those with pre-existing conditions, they offer poor value to healthy Americans, and provide little incentive for individuals to purchase insurance before they get sick.

A reform to health insurance market regulations in Australia offers a good demonstration of the merits of an alternative approach. In 1999, the Australian government allowed insurers to offer discounts to individuals according to the age at which they first purchased insurance – so long as they subsequently maintained continuous coverage. This provided a reward for people to sign up while they were young and healthy, encouraged them to maintain coverage, and allowed them to access appropriately-priced insurance that offered them good value while doing so. The reform was very successful – causing enrollment in private health insurance to surge from 31% to 45% of the population within a year, as people rushed to lock in a discount. It is noteworthy that Australia had previously tried to force people to purchase coverage with a mandate penalty, with little success.[43]

STLDI plans are the only plan options that allow Americans to purchase insurance at a fair price if they sign up before they get sick. Critics of STLDI plans argue that they are often misleadingly marketed, and suggest that they put enrollees at risk with surprise gaps in benefits.[44] States have the legal authority and responsibility to protect consumers from fraud, to ensure that coverage lives up to expectations, and to verify that plans have adequate funds to reimburse claims as promised – and to the extent that they are falling short, they should be doing more in this respect.[45]

Yet, to deliberately suppress all plans that give people lower premiums if they sign up before they get sick, would deprive consumers of good coverage options as well as bad ones. Proposals to restrict STLDI plans to single 3-month terms, while prohibiting their renewability, would serve solely to create a problem of coverage denials due to pre-existing conditions – and surprise gaps in coverage for those who suffer them. Indeed, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners noted that the imposition of 90-day limits on coverage terms forced STLDI plans to dump enrollees as soon as they got sick and develop major medical needs.[46]

It is true that STLDI plans currently offer flawed and incomplete insurance coverage. To fully protect consumers, Congress should proceed in the opposite direction – by requiring that STLDI plans indefinitely guarantee the renewal of coverage to enrollees, regardless of the medical conditions they may develop. Not only would this protect enrollees from future denials of coverage when they get sick, but the creation of longer-term adherence to plans would encourage insurers to bolster the coverage of preventive medical services (such as prescription drugs), and help spread up-front administrative costs over longer periods of enrollment.

To the extent that policymakers are afraid that STLDI plans offer unfair low-priced competition to ACA plans, they should bear in mind that STLDI premiums increase in proportion to term lengths, due to variation in the extent of protection plans offer from long-term major medical risks.[47] An insurer that is prohibited from covering enrollees for more than 3 months can easily avoid covering individuals’ full courses of treatment after they get cancer; but if plans are required to renew coverage for multiple years, they will be required to bear all associated costs.

The most effective way for legislators to pull consumers out of junk plans is to allow better insurance plans to be made available where they can; not by forcing insurers to make non-ACA plans junkier. Extending the renewability of STLDI plans would force plans to bear costs of major illnesses that develop, while reducing the risk of denials of coverage due to pre-existing conditions when terms expire. Restricting the maximum permitted term length serves only to increase the danger that consumers will be tempted by low premiums into plans that expose them to gaps in coverage, which they may discover only when it is too late.

Endnotes

[1] https://www.cdc.gov /nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/Insur201808.pdf#page=14 ; https://www.kff.org/health-reform/perspective/how-buying-insurance-will-...

[2] https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/256751/IndividualMarketPremiumChan...

[3] https://www.ehealthinsurance.com/resources/affordable-care-act/much-heal...

[4] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/2017-premium-changes-and-i...

[5] https://www.cms.gov/httpswwwcmsgovresearch-statistics-data-and-systemsst... ; https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/insurer-participation-...

[6] https://www.nber.org/papers/w22213.pdf

[7] https://siepr.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/15-012_0.pdf...

[8] https://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/healthcare/328122-trump-can-fix-h... ; https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/08/03/2018-16568/short-te...

[9] https://www.manhattan-institute.org/renewable-term-health-insurance

[10] https://www.uhone.com/api/supplysystem/?FileName=45807P-G202008.pdf#page=5 ; https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-plan-selec...

[11] https://www.manhattan-institute.org/renewable-term-health-insurance

[12] https://shoppers.bcidaho.com/resources/pdfs/access-plans/2020-Access-Pla...

[13] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-10/obamacare-health-insu...

[14] https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/mshepard/files/mshepard_hospitalnetwor... HMOs cover only in-network providers, whereas PPOs also provide limited reimbursement for out-of-network providers.

[15] UnitedHealthcare Choice Network.

[16] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-po... https://news.ehealthinsurance.com/_ir/68/20191/eHealth%20Short-Term%20Co...

[17] https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2019-01/54915-New_Rules_for_AHPs_S... ; https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56622

[18] https://news.ehealthinsurance.com/_ir/68/20191/eHealth%20Short-Term%20Co...

[19] https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/cms-makes-no-change-to-silver-loadin...

[20] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/tracking-section-1332-state...

[21] https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2011/02/pdf/g...

[22] https://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/individual-mandate-unnecessary-...

[23] https://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/individual-mandate-unnecessary-... ; https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports...

[24] https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/data-note-changes-in-e...

[25] https://www.conor-ryan.com/uploads/8/5/2/0/85203876/marketstructureandad...

[26] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.3982/ECTA13434

[27] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/06/20/2019-12571/health-r... https://economics21.org/should-we-move-away-employer-sponsored-insurance

[28] https://healthcare.mckinsey.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Reducing-laps...

[29] https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.212.1013&rep=re...

[30] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/10/opinion/obamacare-repeal.html; https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/reports/2010/08/05/82...

[31] https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/reports/2010/04/08/77...

[32] https://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/individual-mandate-unnecessary-... ; https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/if-the-gop-kills-the-health-insuran...

[33] https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo...

[34] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2017/new-executive-order-expanding...

[35] https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/news/2018/01/09/44460...

[36] https://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-How-Repeal-of-the-Individual...

[37] https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-04/hr1010.pdf

[38] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-average-be...

[39] https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/individual-insurance-m...

[40] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-average-be... https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/256751/IndividualMarketPremiumChan... ; https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/2020-aca-marketplace-premiums/

[41] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/average-marketplace-pr... https://www.healthinsurance.org/assets/img/landing_pages/stm_pdf/state-b...

[42] https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/Do... https://www.manhattan-institute.org/renewable-term-health-insurance

[43] https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.8.9192&rep=rep1...

[44] https://energycommerce.house.gov/newsroom/press-releases/ec-investigatio...

[45] A GAO report investigating sales of non-ACA compliant insurance plans found deceptive sales associated with limited benefit insurance, but none associated with STLDI plans: https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/708967.pdf#page=10

[46] https://www.naic.org/documents/government_relations_160809_hhs_reg_short...

[47] https://twitter.com/CPopeHC/status/1303153489661526016

______________________

Chris Pope is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and author of a recent report, “Taking the Strain Off Medicaid’s Long-Term Care Program.” Follow him on Twitter here.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).