Still the Ones to Beat: Teachers’ Unions and School Board Elections

Introduction

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the nation’s school boards were often praised as responsive and representative engines of American democracy. Especially when juxtaposed with our national and state political institutions, board members are portrayed as less polarized and less prone to special-interest capture. According to one widely cited study, not only are local school boards responsive to the preferences of ordinary Americans, but they are mostly immune from the influence of teachers’ unions that, these scholars conclude, do little to diminish the degree to which boards represent the public’s interest.[1]

Experts aren’t the only ones who have tended to paint this rosy, pluralist perspective.[2] Teachers’ unions have also been reluctant to admit that they dominate school board elections, calling their clout more myth than reality. For example, education reporter Sameea Kamal recently interviewed a California Teachers Association (CTA) spokesperson who, in Kamal’s characterization, “disputed that teachers’ unions have too much influence over school boards, saying that ‘the real power resides in parents, educators, students and communities working together.’”[3]

Occasionally, experts have acknowledged that school boards suffer from political inequality. Yet most of this criticism downplays union power and instead focuses on the lack of racial diversity on boards,[4] the power of business,[5] or the influence of homeowners.[6] Some scholars even claim that corporate influence in public education has grown stronger in recent years.[7] According to some of these critics, a neoliberal alliance of school choice advocates and corporate philanthropists is buying school board elections in its larger quest to privatize public education.[8]

Contrary to these assessments, this paper marshals an array of evidence to show that school board elections in the large and diverse states of California, New York, and Florida are neither pluralist nor dominated by a new breed of corporate school reformers or parents’-rights advocacy groups. Instead, I find that, with one important exception, school board elections continue to be dominated by teachers’ unions.

Drawing on a variety of evidence, this paper shows that:

- Teachers’ unions dominate local school board elections: they win seven out of 10 races.

- Union support makes the difference for incumbents as well as challengers and is often more powerful than the incumbency advantage.

- Nonpartisan elections enable union-favored candidates to win board seats in deep blue as well as deep red communities.

- Contrary to some expectations, the Supreme Court’s Janus decision has not reduced union power and influence in school board politics. A full decade after the Tea Party–led union retrenchment movement, union-backed candidates still remain the ones to beat.

- As parents’-rights groups seek to influence school board elections, the best evidence so far points to electoral reforms and gubernatorial advocacy as the most promising ways for these groups to counterbalance union power.

Why School Boards Matter

Inattention to teachers’-union power in school board elections is not surprising. It is challenging to study local elections. Measuring union influence in these backwater elections is exceedingly difficult. University of California–Berkeley political scientist Sarah Anzia observes: “Research on local politics in the United States tends to ignore interest groups, and research on interest groups tends to ignore local government.”[9]

But the lack of good data is just one reason for this inattention. In recent decades, the increased centralization of American education drew scholarly and public attention away from local school districts and emphasized education politics at the state and federal levels.[10] But there are two important reasons to keep a close eye on teachers’-union electioneering in local school politics.

First, the demise of local control in American education is greatly exaggerated. One need to look no further than the Covid-19 pandemic to see that the relationship between unions and school boards played a key role in prolonging school closures in the United States. Even after numerous studies showed that schools could reopen safely,[11] politicians learned how difficult it was to reopen schools when local boards and teachers’ unions resisted.[12] While more centralized education systems in other parts of the world reopened far more quickly, in America’s highly decentralized education system, the inability of school boards to ink reopening agreements with their local teachers’ unions played no small role in keeping half of all students out of school for a full year.[13] Education scholar Brad Marianno explains why we underestimate teachers’-union influence in education when we pay little attention to their power in school board politics: “There are far more education interest groups and competing education policy ideas at the state level, making it much more difficult for a single organization to garner a dominant voice among policymakers. When these [school reopening] decisions are brought down into local school board meetings, there remain only a few organizations that are organized enough to exert influence. The teachers’ unions are the largest elephant in the room.”[14]

Figure 1 illustrates these dynamics by comparing the amount of remote versus in-person instruction that students received relative to how generally active teachers reported that their local union is in local school board elections. As the figure shows, students who attended school in districts where their teachers’ unions are very active in electioneering were the least likely to receive significant in-person instruction during the 2020–21 school year.

Figure 1

Share of 2020–21 School Year Students Spent Learning Outside the Classroom by Teachers’ Unions Political Activity

A second reason to pay greater attention to unions in school board elections relates to their role in the policymaking process. Even when federal and state authorities enact promising reforms, school boards are often the ones that must implement them.[15] Implementation is not just a technocratic process immune from interest-group politics. To the contrary, school board members can, and often do, face pressure (including electoral pressure) to satisfy the preferences of groups (like teachers’ unions) that remain among the most organized and active players in district politics.[16] Narrowly focusing on federal and state politics will lead us to overlook all the important politicking that goes on beneath the radar.

Consider the claim that teachers’ unions lost political clout in recent years.[17] Proponents of this perspective often point to various education reform debates—on charter schools, teacher pay, and evaluation reform—that unions supposedly “lost” during the Bush and Obama years. But when one looks below the surface, many of those same reforms fizzled when local officials encountered resistance from teachers in the trenches. Even after states adopted tougher teacher evaluation laws, for example, most districts simply went through the motions—giving favorable ratings to most teachers and removing few low-performers.[18] Likewise, when states passed new laws encouraging districts to replace union-favored salary schedules with performance-based pay, districts tended to demur in the face of educator resistance.[19]

Altogether, elected boards provide unions with another, often less competitive, political arena for them to shape education policy. Union power in American education, therefore, still hinges on the degree of influence that teachers’ unions can exert in school board elections. It is these elections that determine whether the officials who will implement education policies will be sympathetic to unions’ concerns or resistant to them.

Union Supremacy or Political Pluralism: What Previous Research Shows

Teachers’ unions attempt to shape the composition of school boards in two basic ways. First, they endorse candidates who they believe will be responsive to their members’ interests. Second, they recruit sympathetic educators and union members to serve on school boards. Has it worked? Here’s what existing research shows.

The earliest studies were carried out by Stanford University’s Terry Moe in the early 2000s.[20] Drawing on a survey of about 500 candidates in more than 250 California school districts, Moe found that unions were enormously successful in getting their favored candidates (76% of them) elected to office. He also found that union support was as powerful a factor as incumbency in predicting whether a candidate won.

Moe’s studies offered additional insights. First, he showed that occupational self-interest promoted union mobilization efforts. Teachers who lived outside the district where they taught were not very likely to vote in school board elections, which would elect board members for a district where they are not employed. But teachers who lived where they worked turned out anywhere from two to seven times more than other citizens. In short, Moe showed that the ability of unions to mobilize teachers to elect sympathetic politicians is driven by the rational self-interest of school employees—the chance for them to help elect their employers.[21]

Evidence of this dynamic comes from other indicators, too. A few years after Moe did his California analysis, Rick Hess recalled how Moe’s 400-page treatise, Special Interest, “point[ed] out that the Michigan Education Association [had] distributed a 40-page instructional manual for local leaders that [was] entitled ‘Electing Your Own Employer, It’s as Easy as 1, 2, 3.’ ” Little wonder that “one high-ranking state union official” told Hess in an interview: “ ‘We knew the [public] school system wasn’t moving to Mexico,’ so there was no reason to work with the state negotiator on establishing a prudent salary structure.”[22]

Importantly, Moe’s research also showed that union electioneering creates the conditions for more union-friendly boards. Winning candidates who were endorsed by teachers’ unions held more pro-union attitudes, especially on collective bargaining issues, than unendorsed candidates who lost. A few years later, scholars Katharine Strunk and Jason Grissom found even more evidence that successful union electioneering begets more union-friendly board policymaking. Returning to California, these authors showed that school boards that were composed of more educators and more union-endorsed members adopted more union-friendly contracts.[23]

Other research shows that teachers’ unions are quite successful at electing current and former educators (including their own members) to serve on school boards. My recent book, for example, examined nearly a dozen surveys of school board members that showed that more than 20% of all school board seats are held by current or former educators. About one in 10 boards in California were held by educator-majorities.[24]

None of this is to say that teachers should not bring their expertise to the board table. Rather, it speaks to a lack of political pluralism in many districts. Former military officer Cara Marion, who lost her Florida school board election to a union-backed teacher-incumbent in August, put it this way: “We [elected school board members are] supposed to be a good cross-section of society. You know, people from all walks of life should sit on a board, not just career educators.”[25]

Marion is right on the trend. Educators are significantly overrepresented on the nation’s school boards relative to their share of the population. Does this state of affairs help teachers’ unions influence school board policy? There are certainly reasons to think so. Outside of education, research has shown that interest groups can secure more policy influence inside of government when they are able to elect public officials who share their occupational interests.[26] In a clever study that leveraged the order in which school board candidates’ names appeared on the ballot, economists Ying Shi and John Singleton found that California school districts that elected one additional teacher board member increased teachers’ salaries and authorized fewer charter schools.[27]

Based on their own behavior, union leaders seem to believe that electing more educators, as well as more of their own members to school boards, can help them influence district decision-making. In New York, for example, the state’s largest teachers’ union, New York State United Teachers (NYSUT), launched “Pipeline Project,” which can be used to help them “groom union friendly candidates.”[28] In 2018, NYSUT described the operation as one that has “encouraged, trained and helped elect more than 100 educators to public office over the last four years.” In 2022 alone, the union reported that the program helped elect “60 NYSUT members … to school boards in every corner of the state.”[29]

Still, many have argued that the nation’s teachers’ unions’ most powerful days are behind them.[30] After all, a lot has happened in both American politics and education since the earlier studies of union electioneering were carried out. For example, the political environment facing teachers’ unions in the aftermath of the Great Recession has been characterized by greater austerity and significant labor retrenchment. Teachers have also faced greater competition from new education reform advocacy groups and, most recently, from parents’-rights groups during the pandemic. In 2018, teachers’ unions were dealt a major financial blow with the U.S. Supreme Court’s Janus decision, which overturned state laws obliging nonunion employees to pay fees to unions that are their “exclusive bargaining representative.”[31]

Consequently, some scholars have begun to speculate that these changes may have narrowed union power in school board elections. In a recent study of board elections in five large districts, political scientist Sarah Reckhow and her colleagues found that networks of wealthy donors enabled reform candidates to match or exceed the funds raised by union-backed candidates. While these authors were careful to acknowledge that these competitive dynamics are probably not representative of “the broad universe of districts with elected boards,” they nevertheless see more pluralist dynamics at work in school board elections today. “Teacher unions,” they argue, “have often been portrayed as the eight-hundred-pound gorilla in local school politics—and our evidence already shows that this image is overblown—but the Janus decision throws up new barriers for unions’ political efforts.”[32]

Ultimately, quantifying how influential teachers’ unions are in school board elections is an empirical question. But until now, the absence of good data has made it an impossible one to answer with much certainty. In what follows, I discuss the creation of a new data set tracking union electioneering efforts in school board elections.

Research Design to Analyze Union Electioneering

As part of a few different research projects over a period of several years, I collected data on nearly 5,000 union endorsements in school board elections.[33] These endorsements were gathered for three of the nation’s four largest states: California, Florida, and New York. The California data include endorsements in contests held annually between 1995 and 2020. In Florida, where board elections are held in even-numbered years, the panel runs biennially, from 2010 to 2022. In New York, I have detailed data for 2022 elections, along with some aggregate results reported by the Empire State’s largest teachers’ union for 2015 and 2019.

These three states were chosen for strategic reasons, with each state offering specific advantages and disadvantages. One goal of this paper is to compare the state of union influence today with that of the past; therefore, returning to California for comparison makes sense because the majority of research on board elections comes from the Golden State.

However, one concern with focusing exclusively on California and New York is that public-sector unions are especially powerful there. These states’ labor laws provide some of the most teachers’-union-friendly environments in the country. Florida provides an attractive alternative. It, too, is a large and diverse state; but labor law in the Sunshine State has historically been less favorable to teachers’ unions. Although Florida teachers have enjoyed collective bargaining rights since the mid-1970s, the state’s long-standing right-to-work law has made it more challenging to organize teachers. In contrast to New York and (until recently) California, Florida’s elections are held “on-cycle,” when voter turnout is higher and research shows that unions may be less dominant.

The process of gathering endorsements required triangulating from several sources.[34] In California, this approach yielded 4,075 endorsements conferred on 3,336 unique individuals running in 2,345 elections in 468 of the state’s 977 public school districts. Notably, these 468 districts—while by no means perfectly representative of California districts as a whole—combine to represent roughly half the state’s regular local school districts. Moreover, the 2,345 elections where I was able to find evidence of union electioneering combine to represent a little over 26% of all competitive school board elections held between 1995 and 2020 in the Golden State. In Florida, 1,109 board seats were up for election between 2010 and 2020. However, just 722 of those seats generated any competition. I was able to identify union electioneering in 361 of these 722 races (50% coverage).[35] These 361 contests took place in 36 of the state’s 67 public school districts. For New York’s 2022 elections, NYSUT released information on just over 340 candidate endorsements. However, after eliminating write-in candidates and endorsements in noncompetitive elections, my roster of Empire State endorsements shrank to just under 320.[36]

How representative are the school districts in my sample? With one exception, the districts are highly representative of districts in their respective states. The one exception is that endorsements were less numerous in smaller rural districts. On the one hand, this limits my ability to generalize my findings to very small rural communities. On the other hand, the districts in my sample—those where unions regularly make endorsements—are the ones that educate the majority of all public school students in each state (roughly 90% in California and Florida and about 50% in New York, after excluding New York City, which does not have an elected board).[37]

Before proceeding to the results of the report’s analyses, it is important to mention a few key differences related to how board elections work in these states. With the exception of districts that use ward-based elections, New York and California hold “multi-seat elections,” where citizens vote for several candidates in a single contest. By contrast, like many Southern states, Florida districts are large and countywide, meaning that voters vote only for a single candidate in each contest. Importantly, Florida holds its board elections entirely in even-numbered years, whereas California has only recently transitioned to a system where elections are uniformly held “on-cycle” and New York holds elections in May.[38] These two factors (the use of on-cycle elections combined with larger countywide districts) should, if anything, make it harder for any single interest—including teachers’ unions—to dominate district politics in Florida.

Key Findings on Union Power

Teachers’ Unions Win Most Competitive School Board Elections

Consistent with Terry Moe’s findings from his early California studies, union-backed candidates are the ones to beat. As Table 1 shows, union-endorsed board candidates have done exceptionally well in competitive elections held across all three states. In New York, unions won 80% of competitive races in 2022 (that bumps up to 88% when one includes elections in which the union-backed candidate, typically a union-favored incumbent, scared off any would-be challengers). In California, union-backed candidates took seven out of every 10 seats. Finally, in Florida, where we should expect that unions won’t make much of a showing, they do surprisingly well: 64% of endorsed candidates there prevailed. Despite the fact that Florida’s teachers’ unions operate at a comparative disadvantage (relative to unions in California and New York), they appear to more than overcome the dual headwinds of on-cycle elections and a more conservative-friendly electorate.

Table 1

Percentage of Union-Endorsed Candidates Winning School Board Seats, by State

Union Support Is Often Pivotal, for Both Incumbents and Challengers

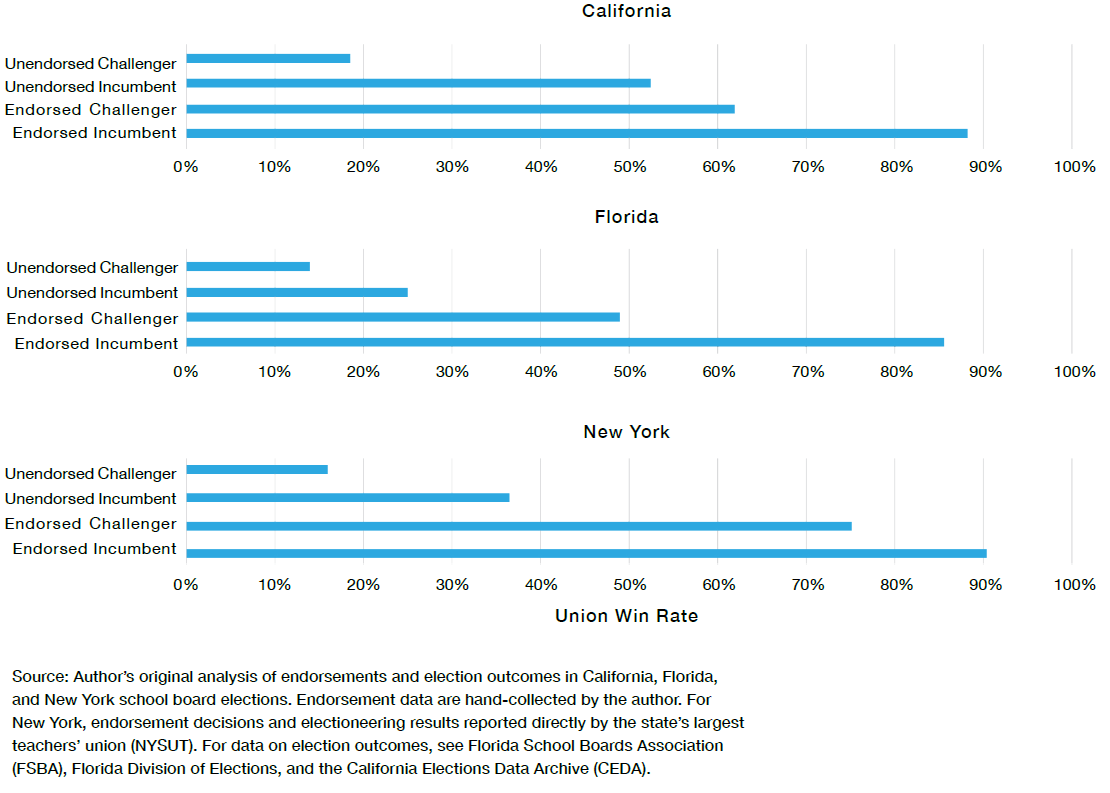

Figure 2 disaggregates the results shown in Table 1 separately by candidate type, showing just how well incumbents and challengers fare when they run with (or without) union support. Three patterns in the data stand out.

First, it is almost always better to be an endorsed challenger than an unendorsed incumbent. Although the incumbency advantage is typically huge in American politics, union support matters far more in school board elections. This finding is robust to more sophisticated statistical analyses that use multivariate regression to compare the effects of endorsements and incumbency directly. In fact, whereas previous studies have estimated union support to be equal to the power of incumbency,[39] I find that union support matters more than incumbency, particularly in more recent elections.[40]

Figure 2

Rate of Electoral Victory for School Board Candidates, by Incumbency Status and State

Second, endorsed incumbents rarely lose, while unendorsed challengers are a long shot to win. These findings speak directly to why some of the new parents’-rights groups that emerged during the pandemic have found only mixed success in their first years of supporting candidate slates.[41] Getting challengers elected to school boards is tough sledding, unless you have the resources and voter mobilization operations that can compete with establishment union interests.

Third, I probed whether union-backed candidates tend to win simply because the unions strategically support candidates who are already more likely to win. By following the same candidates over time, I compared how they performed in races where they received union support relative to ones where they were not endorsed. This analysis revealed that union support matters: gaining an endorsement enabled losers to become winners, and losing union support cost incumbents from winning reelection.[42] In other words, union-endorsed candidates are not more likely to win school board elections simply because they are stronger candidates ex ante but rather because union support confers an advantage that makes endorsed candidates more formidable on Election Day.

Teachers’ Unions Win in Both Blue and Red School Districts

The results presented in Table 1 and Figure 2 are just a starting point. Remember, some have claimed that union power has weakened in recent years, especially on the heels of a decade of labor retrenchment capped off by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Janus decision. To evaluate how influential unions are today relative to the past, I next examine: (1) whether their influence has narrowed to liberal districts; and (2) how successful union electioneering has been over time.

Given increases in partisan polarization, the rise of culture-war issues in education during the pandemic, and more nationalization of local U.S. politics,[43] it is worth seeing whether union influence is geographically narrow. To investigate whether union electioneering packs a punch only in districts with liberal, pro-labor electorates, I calculated union electoral outcomes separately for Republican-, Independent-, and Democratic-leaning school districts. Drawing on two proprietary industry data sets that classify and predict every registered voter’s political party, I geocoded all registered voters to their school district of residence. After measuring the two-party registration advantage held by Republicans in each school district, I cut these data into terciles that range from strong GOP districts, independent-leaning districts, and strong Democratic districts.[44] Figure 3 shows how union-endorsed candidates fare in these various political environments.

On the whole, union electioneering is successful in liberal, moderate, and conservative districts.[45] For example, union-backed candidates never win less than 60% of their elections, even in the most GOP-leaning districts. Only in New York (where data are the most current, since the elections occurred in May 2022) do we see union-backed candidates fare somewhat worse in Republican districts. Still, they win nearly 70% of the time in these GOP-friendly districts. This suggests that while partisanship may have begun to collide with union strength in our current political environment, it is constraining union power only at the margins. These findings are important because they suggest that—given our current system of nonpartisan school board elections—partisanship in and of itself is not enough to act as a check on union power in local school politics.

Figure 3

Union-Backed Candidates’ Election Rate by Partisan Lean of School District

Union Endorsements Still Matter

What about the claim that teachers’ unions have grown less powerful over the last decade?

There appears to be little support for this claim when we look at union electioneering outcomes over time, as illustrated in Figure 4, which highlights a number of important trends. First, union-endorsed candidates are consistently more successful than are unendorsed candidates, irrespective of the prevailing national political environment facing teachers’ unions at any particular point in time. For example, union-backed candidates did just as well during 2010 (when antiunion governors, such as Scott Walker in Wisconsin, rose to power) as they did during 2018–22, when the conservative brand was arguably weakening in national politics.

Figure 4

Union-Endorsed Candidates’ Electoral Success over Time, by State

Across nine election cycles in California, in no year do union-endorsed candidates win less than 60% of the time. In Florida, union-backed candidates meet or exceed the 60% win rate in all but one election cycle (where they narrowly miss it in 2012). In New York, the unions report winning nearly nine out of every 10 contests where they get involved—an even higher clip than in California.

Second, careful attention to Figure 4 highlights the resilience of teachers’ unions in the post-Janus era. The comparison between Florida and California in 2016 and 2020, as well as Florida and New York between 2015 and 2019–20, is instructive. Florida’s right-to-work law always prohibited teachers’ unions from charging nonmember teachers agency fees prior to the court’s 2018 Janus decision. The ruling, therefore, had no direct effect on Florida’s unions. California and New York are an entirely different story. The labor laws in these states previously required that all teachers—union member and nonmember alike—pay union fees. To the extent that Janus weakened teachers’ unions politically, then, we should see a decline in their power in California and New York. Yet the data show no such reversal in either state.

Political Lesson: Change the Electoral Environment for Voters

For political conservatives, parents’-rights groups, education reformers, and school-choice advocates wishing to counteract union dominance in local school politics, there are important lessons to be learned. These groups cannot simply rely on favorable partisan tides in national politics or narrow legal decisions that weaken unions to advance their cause. After all, school board elections are fought and won in the trenches.

According to American Enterprise Institute’s Max Eden:

The fact that school board members are … elected in off-cycle, nonpartisan elections renders local control largely chimerical. If we want a public education system that caters to the cultural, policy, and pedagogical preferences of communities, then we should ensure that more citizens participate in local school board elections—and that they have a clear idea about what the candidates stand for. To boost election turnout, school board elections should be moved on cycle (i.e., held on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November of an even year). And to boost the signal as to what candidates stand for, school board ballots should allow partisan affiliation to appear next to candidates’ names.[46]

Taking Eden’s two points in turn, what about the timing of school board elections?

Looking back at Figure 4, union-endorsed candidates are far more likely to win their elections in off-year races. The difference is significant, and it is far more likely to be a story of causation rather than one of simple correlation. How can we know? In 2015, California enacted a sweeping election consolidation law (SB-415) that forced numerous school districts to move their elections from odd to even years.[47] By comparing changes in union win rates in districts that were forced to switch to on-cycle elections with changes in win rates for districts that always used on-cycle elections, I estimate that on-cycle elections reduce the share of union-endorsed winners by about 8 percentage points.

But reforming the election calendar isn’t the only way to inject more balance and political pluralism into local school politics. Eden’s second idea—partisan school board elections—can be achieved without enacting a single actual electoral reform.

Earlier in this report, I noted that in examining decades of union electioneering in three of the nation’s four largest states, I found just one exception to union dominance in school board elections. That exception was something of a natural experiment that took place in Florida’s 2022 primary contests (the de-facto general election for school board races with just two candidates). Although Florida’s school board elections are nonpartisan, something unprecedented happened in this most recent election: Governor Ron DeSantis and the Republican Party of Florida put school board elections on their agenda.[48]

During the summer leading up to the August primary election, DeSantis unveiled a 10-point education agenda and asked local school board candidates to pledge their support for it. After candidates decided whether to align with the governor’s conservative education agenda, DeSantis chose 30 candidates, offering them his official endorsement and financial support.[49] In certain hotly contested races, DeSantis even campaigned locally on behalf of the candidates. The move was unprecedented. “This is new, particularly for Republicans,” DeSantis told the News Service of Florida. “Because … [traditionally] unions would back candidates and that would be it. And so now, I think more parents are interested, some of our voters are interested. We have no consequential races, really, statewide that are competitive. So you have a situation where this may be one reason why people are motivated. So we tried to help out.”[50]

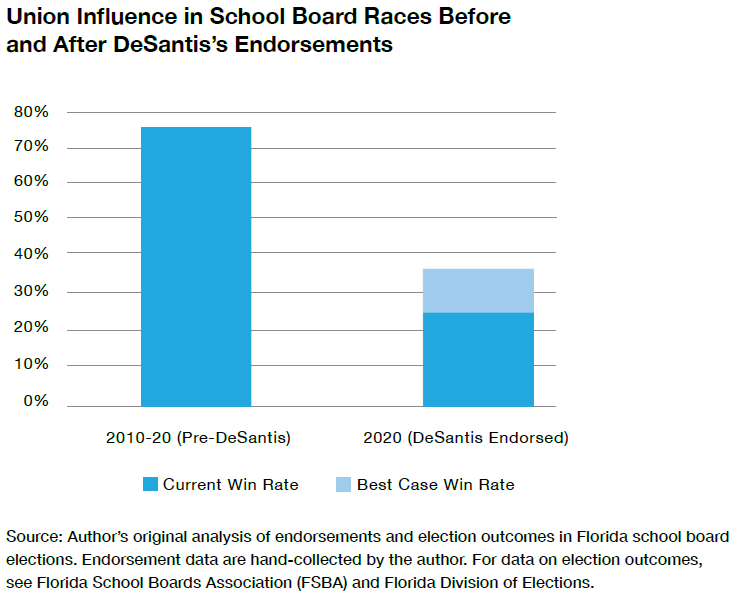

Figure 5 shows the share of union-endorsed candidates in Florida who won a school board seat in 2022 when facing an opponent backed by DeSantis, compared with the share of union-endorsed candidates who won in the very same districts in the decade prior (2010–20) to the governor challenging union-backed slates.

Figure 5

Union Influence in School Board Races Before and After DeSantis’s Endorsements

DeSantis’s move worked on a scale unlike anything seen before. In the 19 elections where one of the governor’s candidates went head-to-head with a teachers’-union-backed opponent, the unions won just four races (and advanced to a general-election runoff in just three). Figure 5 shows how effective muscular gubernatorial advocacy proved to upset establishment union interests in Florida. The figure compares how union-backed candidates performed in the very same districts where DeSantis made his endorsements prior to 2022 with their showing in the most recent August primary. In those previous elections where voters did not have the same cues to follow, teachers’ unions won over 70% of the time when they made an endorsement. In contrast, the very best outcome that Florida’s teachers’ unions will be able to achieve in 2022 in districts where DeSantis got involved will be about 40% (depending on how they fare in the November runoffs).

The key advantage of the DeSantis strategy is that it requires no electoral reforms. Moreover, the DeSantis approach is available to both Democratic and Republican governors who believe that their education agendas are sufficiently popular with voters to provide coattails to local school board candidates who buy in. Although some election law scholars have made a good case for adopting electoral reforms that would allow political executives (mayors, governors) to make on-ballot endorsements,[51] DeSantis proved that, even absent these formal legal changes, a recognizable political figure with a clearly articulated education policy agenda can make races more competitive by endorsing aligned school board candidates and campaigning on their behalf.

Conclusion

The academic, media, and political establishment talk unremittingly about political inequality in the United States. To be sure, studies have shown that politicians often respond more to the preferences of wealthy elites than to the poor or downtrodden in state and national politics.[52] Similarly, using data from California, New York, and Florida, I find that school boards are characterized by a great degree of political inequality. But it is not the sort of inequality that critics of the education reform movement, parents’-rights groups, and the business sector decry when they raise concerns about democracy in public education today.

Instead, the findings of this report build on a growing body of research showing that it is teachers’ unions and other public-sector unions that often wield unequal power in municipal and local school politics.[53] To summarize, my findings underscore how the dominance of teachers’ unions in school board elections challenge pluralist characterizations of school board politics.

- Union-endorsed candidates still win roughly 70% of all competitive races.

- Union support appears to exert a strong causal effect on election outcomes. By examining how the same candidates perform over time, I show that gaining a union endorsement enables losers to become winners the next time around.

- Union-favored candidates tend to win in both strong (CA, NY) and weak (FL) union states and in conservative and liberal school districts. There is no evidence that the unions’ electioneering success is narrowly confined to districts where voters hold politically liberal, pro-union attitudes.

- There is no evidence that the unions’ impressive win rates have declined in recent years. Neither the Great Recession nor the loss of agency fees has materially weakened their electioneering successes.

- The best way to bring pluralism to school board elections is to move elections on-cycle and provide voters with more information (including partisan cues) that help counteract the low-information environment that is characteristic of nonpartisan contests.

Taken together, the bigger-picture landscape of interest-group competition in school board politics is … well, that there isn’t much competition.

It’s little wonder that, just when education-reform and parents’-rights groups have gotten more involved in school board elections because of the pandemic, the education establishment has begun to cry foul. Earlier this year, when Governor Ron DeSantis became involved in endorsing school board candidates, his detractors said that he was “politicizing” school boards. One Florida-based columnist even called it “a little scary,” asking, “Wouldn’t we rather have [school board] candidates who commit to serving our children and local taxpayers/communities first, rather than the governor? This isn’t some banana republic or socialist or fascist state, right?”[54]

One wonders where these critics were for the past three decades, when research showed (and continues to show) that teachers’ unions dominate local school board elections. While that dynamic is unlikely to change anytime soon, there appears to be a reasonable blueprint for advocates of more pluralism in local school politics on which to build.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).