Teacher Strikes and Legacy Costs

After many years of labor peace, public school teachers have engaged in strikes and work stoppages in record numbers during the past two years. The big wave came in 2018. Large-scale teacher walkouts occurred in Oklahoma, Kentucky, Arizona, and West Virginia. Smaller-scale protests occurred in numerous counties in North Carolina and Colorado. What made these union-led protests particularly surprising was that they occurred in states where union membership is low. In early 2019, a second, smaller wave of strikes occurred in “blue” cities such as Los Angeles and Denver, as well as in a number of smaller school districts around the country.

Chief among the demands of striking teachers was higher pay. Discontent was also expressed with working conditions, which teachers and their unions connected to flat or declining state spending on education.

This report argues that underfunded defined-benefit pension plans and other post-employment benefits (OPEB) are the hidden drivers of labor unrest in the public sector. As these legacy costs have risen, teacher salaries have flatlined or even declined in value.

Policy recommendations:

- In the name of equity and affordability, states should move away from defined-benefit pensions and toward defined-contribution plans.

- More of the money currently spent on education should show up in the paychecks of working teachers.

- States should consider eliminating retiree health-care benefits for newly hired teachers—indeed, for most government employees. These kinds of benefits have been sharply pared or eliminated throughout the private sector.

- To implement these reforms, states could offer teachers a deal wherein raises in salary are matched with switching to a defined-contribution plan. This would have the double benefit of giving younger teachers, with lots of time to save for retirement, a bigger raise in the here-and-now, as well as reducing the government employers’ long-term pension liability.

Introduction

America’s public school teachers frequently walked off the job in the 1960s and 1970s.[1] But the number of work stoppages in education and the entire economy declined dramatically after President Ronald Reagan broke the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike in 1981 by firing and replacing 11,345 federal employees.[2] Contrary to that trend, public school teachers have gone on strike in record numbers in the past two years.

This was particularly surprising, since the uptick in strikes occurred in states where union membership is low. The big wave came in 2018. Teacher walkouts occurred in Oklahoma, Kentucky, Arizona, and West Virginia. Smaller-scale protests occurred in numerous counties in North Carolina and Colorado. These work stoppages were dubbed “red” state strikes because Republicans tend to control these state governments. Teachers in Arizona coined the slogan “#RedforEd.” In early 2019, a second, smaller wave of strikes occurred in “blue” cities such as Los Angeles and Denver, as well as in a number of smaller school districts in Oregon, California, and New Jersey.[3]

Among the causes of the teacher unrest, salaries were first in importance. Teacher pay in the six affected states is below the national average—and significantly so in four states (Figure 1). Kentucky teacher salaries rank 29th nationally, at $52,338; Arizona 44th, at $47,403; West Virginia 49th, at $45,555; and Oklahoma 50th, at $45,292.[4]

Protests against austerity measures enacted since the Great Recession were also a key issue. Some of the affected states either cut or flatlined education spending over the last decade (Figure 2). For instance, Arizona and Colorado both had lower—inflation-adjusted—education spending in 2015 than they did in 2000. Oklahoma, Kentucky, and West Virginia all increased education spending over that period.[5] Nevertheless, educators have complained about working conditions, particularly larger class sizes.

Some commentators have also claimed that teachers are increasingly politically engaged following Donald Trump’s election in 2016 and the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in Janus v. American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees, Council 31, which declared unconstitutional the fees that public unions charged nonmembers in 22 states. One sign of a new activist spirit is the supposed record number of former educators reported to be running for office.[6]

Hidden Drivers of Educational Spending and Strikes

While there is something to these points, the role of benefit costs in constraining education budgets has been overlooked. This report contends that pensions and other post-employment benefits (OPEB) are hidden drivers of labor unrest. As these costs have risen, teacher salaries have remained stagnant or declined in value. The budgetary pressure of legacy costs is an underappreciated part of the story behind the strikes in Arizona, West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Colorado, and North Carolina.

Put simply, expensive benefits constrain school districts from offering higher salaries to teachers, increasing support staff, and much else.[7] With states contributing more to underfunded pension and OPEB systems, they cannot allocate more to day-to-day school operations. Another consequence of the “pension-cost crowd-out of salary expenditures,” according to one study, is that teacher workloads “in the form o[f] larger class sizes” have been increasing.[8]

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the costs of teacher pensions are at an all-time high.[9] However, teacher benefits are not more generous. To the contrary, many states enacted laws stipulating less generous pensions for newly hired teachers. The reason costs are rising is that 90% of teachers participate in defined-benefit pension plans, and these plans are not well funded. Indeed, they have an unfunded liability of over $500 billion, by one estimate in 2015.[10] (This is unlike 401(k)-style, defined-contribution plans, where benefits increase as contributions increase.) Paradoxically, even as retirement pensions become less generous for new teachers, the entire system costs more. But the pressure of rising pension or other retirement benefit costs is hardly felt by currently employed teachers because their individual contributions, paycheck to paycheck, remain small.

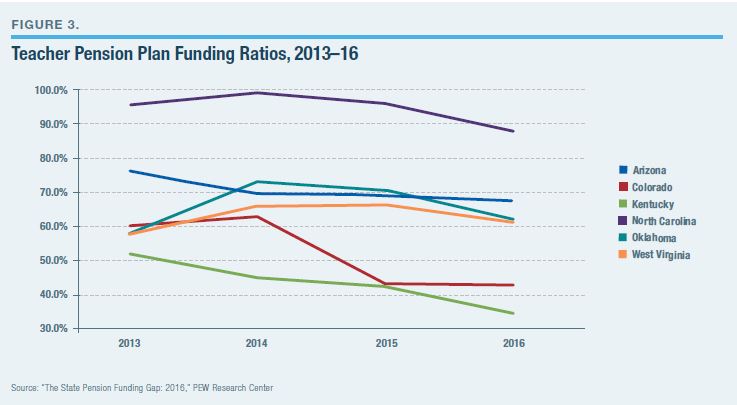

Across the nation, only seven states had pension plans that were 90% funded, none of them in the states experiencing the most teacher unrest in the past two years (Figure 3).[11] To make up for past underfunding, contributions to current pension systems are a form of paying off debt. In Arizona, for example, 82.7% of the employer contribution to the teacher pension system goes to pay off unfunded liabilities. In Colorado, it is 81.4%; in Oklahoma, 77.3%; in Kentucky, 74.4%; and in West Virginia, 81.8%. The national average is about 70 cents on the dollar of the employer contribution going to pay off debt.

“While West Virginia ranks in the bottom five states in teacher salaries,” Bellwethers Education Partners’ Chad Aldeman pointed out, “it ranks in the top five in terms of retirement costs.”[12] He estimates that West Virginia teachers currently forgo compensation equivalent to more than 20% of their salaries just to pay down pension debt.[13]

By one estimate, inflation-adjusted per-pupil pension costs have more than doubled, from $500 in 2004 to over $1,000 by 2015.[14] Meanwhile, overall pension debt and the costs of annual contributions to these pensions for state employees are creeping up, exerting even more pressure on education budgets (Figures 4 and 5).

In addition to pensions, the costs of teachers’ OPEB, primarily retiree health care, have also been rising.[15] The Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) recently began to require states and districts to disclose how much they had promised in these future benefits and how much they had set aside to pay for them. While good data are still hard to come by in this area, one estimate is that, by 2016, states and localities were on the hook for about $231 billion in unfunded OPEB liabilities for teachers and other public education employees.[16]

Teacher Pensions and OPEB: Cui Bono?

While teachers are (sometimes rightly) dissatisfied with the amount of their take-home pay, their total compensation is more than merely salary. Although teacher salaries have not kept pace with inflation, their benefits—health insurance, pensions, and OPEB—have kept pace.[17] Pensions and OPEB are quite generous and expensive. It’s just that working teachers don’t feel those forms of deferred compensation, as they are back-loaded into retirement.

Chad Aldeman has demonstrated that teacher retirement benefits cost twice as much as those for other workers as a percentage of total compensation (10.3% versus 5.3%).[18] Furthermore, teachers receive about 25% of their total compensation in the form of benefits, especially health insurance and retirement benefits, compared with about 13% for private-sector workers.[19] As Figure 6 indicates, benefits are an increasing slice of school employee compensation costs.

There is, however, a bitter irony about these generous retirement benefits: only those teachers who spend their entire careers in a single state or school district will reap the benefits.[20] About one in five teachers remains in the same school system for 25 or 30 years;[21] but anyone who leaves the state loses out on much, if not all, of defined-benefit pensions (in which 89% of public school teachers nationwide are enrolled).[22] OPEBs are similarly confined to the small slice of the education workforce that spends 25–30 years in the same system. These retirement systems, in short, shortchange younger teachers in a way that private-sector employees with 401(k)s or IRAs are not, and the structure of these systems shapes the politics of public education.

A vocal minority of teachers wants to preserve existing pension and OPEB policies. Teachers’ unions have also defended them because teachers are legally entitled to the benefits, and long-serving teachers are more likely to vote in union elections. But the interests of longer-serving teachers and those of younger teachers and the broader public are at odds.

On the employer side, the problem is twofold: more money is paying off past underfunding of pensions, and any teacher salary increase also increases the longterm pension liability. Therefore, increasing teacher salaries is problematic because it also increases the long-term pension liability.

The legacy cost problem is particularly acute in some of the states that have experienced teacher strikes in the last two years. Arizona, Colorado, and North Carolina were among the eight states that “experienced the double whammy of declining per-pupil expenditures and growing pension contributions over the last two decades,” reports Josh McGee of the Manhattan Institute.[23]

From 2000 to 2016, pensions and health-care spending jumped in North Carolina from 16% to 23% of total instructional compensation. Over the same period, the increase in Oklahoma was 15% to 21%; in Kentucky, 17% to 26%; and in Colorado, 13% to 19%.[24] Arizona has modestly cut spending and taxes, which constrains future spending increases, and Oklahoma has held per-pupil spending flat. This means that as the costs of pensions and health care increase, they consume a larger slice of a pie that is not growing.

Teacher frustration and labor protest have been the result.

The Strike Weapon

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), enacted in 1935, protects workers in the private sector from retaliation by employers when they join or attempt to join a union, engage in a work stoppage, or go on strike. The NLRA does not apply to the public sector.

Federal workers have been granted limited collective bargaining rights (first by executive order in 1962, and then by statute in 1978) but are prohibited from striking. Many states also prohibit or limit strikes by public employees—but in some states, public employees who do strike do not face any legal penalties.

The high point of strikes and work stoppages in the public sector occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, reaching a peak in the mid-1970s. Urban public school teachers frequently walked off the job in this period, sometimes as part of an effort to gain or expand their collective bargaining rights under state law. Other strikes also occurred among city police and sanitation workers.

The broad trend since the mid-1970s has been one of a declining number of strikes (Figure 7), a trend given a major push when President Reagan broke the strike by the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) in 1981. “PATCO Syndrome” came to describe the fear of striking and losing.[25] Thus, prior to 2018, there had only been two notable teacher strikes in the previous two decades: a seven-day walkout in Chicago in 2012; and a 16-day walkout in Detroit in 2006.[26]

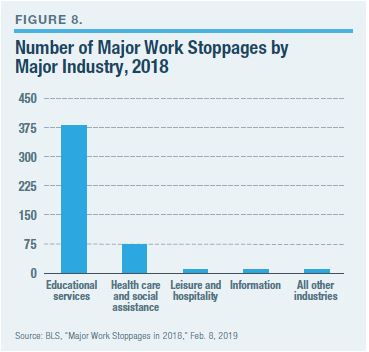

Years of calm gave way to storms as strikes and work stoppages by public school teachers dominated the headlines last year (Figure 8). In 2018, the largest work stoppage was by the Arizona Education Association and involved 81,000 teachers. The second-largest stoppage involved the Oklahoma Education Association and included 45,000 teachers.[27] Overall, the 20 major work stoppages (involving more than 1,000 workers) that year were the most since 2007 and involved the highest number of workers—485,000—since 1986.

Years of calm gave way to storms as strikes and work stoppages by public school teachers dominated the headlines last year (Figure 8). In 2018, the largest work stoppage was by the Arizona Education Association and involved 81,000 teachers. The second-largest stoppage involved the Oklahoma Education Association and included 45,000 teachers.[27] Overall, the 20 major work stoppages (involving more than 1,000 workers) that year were the most since 2007 and involved the highest number of workers—485,000—since 1986.

Interpreting Recent Teacher Strikes

Legacy costs have had a significant role in restraining teacher salaries, helping to explain the strikes and walkouts of the past two years. Even so, the claim by teachers and union officials—widely repeated in the media and accepted by much of the public—that they are underpaid deserves scrutiny. Are teachers, in fact, underpaid?

Teachers and their supporters believe that they are underpaid. The argument here is that, compared with other college-educated professionals, teacher pay is mediocre and has fallen over time. According to one report, among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, the U.S. has the largest pay gaps between teachers and other workers with similar levels of education.[28]

Adjusted for inflation, teacher pay has declined.[29] Today, the average public school teacher earns $56,689 annually, slightly less in constant dollars than two decades ago.[30] And in the states where teachers have walked out, average pay is generally lower than the national average (Figure 1). Even considering the lower cost of living in many of these states, these salaries are on the low side.

Here, too, the pressure on education budgets does not get the attention it deserves. Teachers’ unions have an incentive to hire more teachers because that means more union members—and teachers themselves have pushed to teach fewer students. Moreover, parents like smaller class sizes. However, increased hiring means that school districts spread salary dollars across more teachers. And they also acquire more pension beneficiaries, which drives up liabilities. The result may be stagnant or lower salaries, on average.

Yet there are also persuasive arguments that, despite relatively low salaries and the hidden factors behind them, teachers are not underpaid. The argument here is that teachers enjoy generous benefits packages as part of their overall compensation—not just salary. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation show that teachers who change to nonteaching jobs take an average salary cut of about 3%.[31]

Whatever the case, teacher strikes have boosted public support for increasing teacher pay. A battery of polls bears this out. In an NPR/Ipsos poll conducted in April 2018, just one in four respondents thought that teachers were paid fairly.[32] According to an Associated Press–NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll, 78% of the public believe that teacher salaries are too low.[33] An Education Next survey found that public support for increasing teacher pay jumped to 49% from 36% over the last year.[34]

Apart from salaries, a second cause of teacher discontent is austerity budgeting. Analysts point to declines in state education spending in many states since the Great Recession.[35] Some 47% of K–12 spending nationally comes from state funds (the share varies by state). Cuts at the state level force local school districts to scale back educational services—such as counseling, music, and art—and raise more local revenue to cover the gap, or both. Arizona, North Carolina, and Oklahoma are among seven states that cut general state funding for education by 7% or more and enacted income-tax cuts, reducing the monies available for state support for education. Oklahoma and West Virginia have also suffered lower tax revenues over the last decades, as the budgets of both states have been hit by declines in prices for oil and other natural resources.

Still, American Enterprise Institute analysts Frederick Hess and Grant Addison point out that spending on schools has actually increased nationally (even if not in every jurisdiction), by looking at a longer window of time.[36] The trouble for teachers is that this spending has largely gone to hire more support staff, not more teachers or more pay for teachers. This has occurred while the number of students attending schools has been falling in many districts.[37]

According to Hess and Addison, inflation-adjusted per-pupil spending grew by 27% between 1992 and 2014. In Kentucky and West Virginia, over that same period, teacher pay fell by 3%, even as real per-pupil spending increased by more than 35%. In Oklahoma, over that same stretch, a 26% increase in real per-pupil spending translated into only a 4% salary boost for teachers. Hess and Addison note that in West Virginia, “[i]f teacher salaries had simply increased at the same rate as per-pupil spending, teacher salaries would have increased more than $17,000 since 1992—to an average of more than $63,000 today.”[38] In West Virginia, while student enrollment fell by 12% between 1992 and 2014, the number of nonteaching staff grew by 10%.[39] In Kentucky, enrollment grew by 7% while the nonteaching workforce grew at nearly six times that rate—by a remarkable 41%. Oklahoma saw a 17% growth in enrollment, accompanied by a 36% increase in nonteaching staff.

Conclusion

Arizona, West Virginia, and Kentucky responded to the strikes with across-the-board wage increases. Observers across the political spectrum argue that such a move was unwise. Research indicates that raising teachers’ salaries has only a modest impact on improving teacher quality.[40] Granting raises may have returned teachers to the classroom but is unlikely to improve educational outcomes for kids. Other jurisdictions responded with more limited offers.

Increasing pay also has the long-term effect of increasing pension and other retirement liabilities. It thus exacerbates a problem at the root of the complaints about teacher pay.

Teacher pension systems are not only expensive; their structures are inequitable and misguided. Roughly 75% of teachers will be net losers from their pension plan because they will quit or change school districts before they have reached the minimum years of service to be eligible to receive a pension; or they will retire or leave the system before their contributions and the interest earned on them are more than the pension for which they then qualify.[41]

Even the winners in this pension lottery—the roughly 25% of teachers who remain on the job in the same system long enough to earn substantial retirement benefits—will have traded years of lower salaries in exchange for disproportionately large retirement benefits.[42]

Consequently, it is not obvious that any teachers benefit from the current benefit systems. Meanwhile, the costs of these systems are crowding out spending on salaries and other school priorities—on top of which these systems largely contribute to intense conflicts, such as strikes that punish students, parents, and communities.

To address the flaws in public school teacher retirement plans, policymakers should consider the following steps:

1) States should launch a campaign to better inform teachers about the realities of their pension and retiree health-care systems and make those systems more transparent.

2) States should seek to move away from the traditional defined-benefit model and toward defined-contribution plans that are portable.

3) More of the money in state education spending should show up in the paychecks of working teachers.

4) States should consider following North Carolina’s example of eliminating retiree health-care benefits for most government employees hired after 2021.[43]

In order to make good on steps two and three, states could offer teachers a deal wherein raises in salary are matched with switching to a defined-contribution plan.This would have the double benefit of giving younger teachers, with lots of time to save for retirement, a bigger raise in the here-and-now as well as reducing the government employers’ long-term pension liability.

Ultimately, the reform of teacher retirement systems is a way to address the budget crunch that increasingly leaves teachers, parents, communities—and students—unsatisfied. Otherwise, the drag on schools is likely to generate more disruption and unrest.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).