Rethinking the Goals of NYC High Schools and CUNY’s Community Colleges

Introduction

Each year, more than 55,000 students graduate from the public high schools run by the New York City Department of Education (DOE); 58,000 did so in school year 2019–20. In percentage terms, the city’s cohort graduation rate—that is, the percentage of entering ninth-graders who graduated within four years—has increased steadily from the early 2000s and now stands at 78.8% (Figure 1). In 2000, the graduation rate was 49.9%, about the same level it had been when it was first computed in the mid-1980s.

The meaning, or value, of a high school diploma has been debated during the two decades that the city’s graduation rate increased. The New York State Board of Regents regulates the state’s graduation requirements, and all New York City students must meet them before they can be issued a diploma.[1] Those requirements have changed over the years, nominally in the direction of making them more difficult to meet, toward a goal of equating the diploma with college readiness. In recent years, the Regents have scaled back on that aspiration.[2] Anecdotes have emerged in the press suggesting that teachers have been coerced into giving passing grades to students who have not really earned them.[3] Other reports have questioned whether the Regents exams and their grading criteria have remained as stringent as they once were.[4]

However, questions about the legitimacy of a diploma mask a more fundamental question. Should a high school diploma, of any type, signify college readiness? More generally, is enrollment in an academic course of study in college the only appropriate goal for high school graduates?

This paper will consider these fundamental questions by examining the academic standing of NYC DOE high school graduates (that is, district public schools, not private or public charter high schools) who enter associate’s degree programs in the City University of New York (CUNY), as well as the measurable outcomes, retention, and graduation rates of its colleges. It is based on publicly available aggregate data maintained by the city’s DOE and CUNY’s Office of Institutional Research.[5] The paper is purely descriptive and describes general trends.

High School Outcomes in NYC

New York State awards three types of diplomas. The 77.3% of NYC students who entered high school in 2015 and received a diploma four years later included students who earned:

- A Regents diploma with the advanced designation (21.2%), indicating that they had passed nine state Regents exams in specific subject areas

- A Regents diploma without the advanced designation (49.1%), indicating that they passed five exams

- A local diploma (7.0%), indicating attainment of a score of 55 on five exams (passing these exams requires a score of 65)

Of the students who had not obtained a diploma four years after entering high school in 2015, most had either dropped out (7.8%) or were still enrolled (13.5%).[6] NYC DOE also calculates a college-readiness index for each of its high schools, defined as “the percentage of students in the school’s four-year cohort who, by the August after their fourth year in high school, graduated with a Local Diploma or higher and met CUNY’s standards for college readiness in English and mathematics.”[7] Aggregating those data from 2018–19 indicates that 62.5% of the students who graduated that year were deemed college-ready.[8]

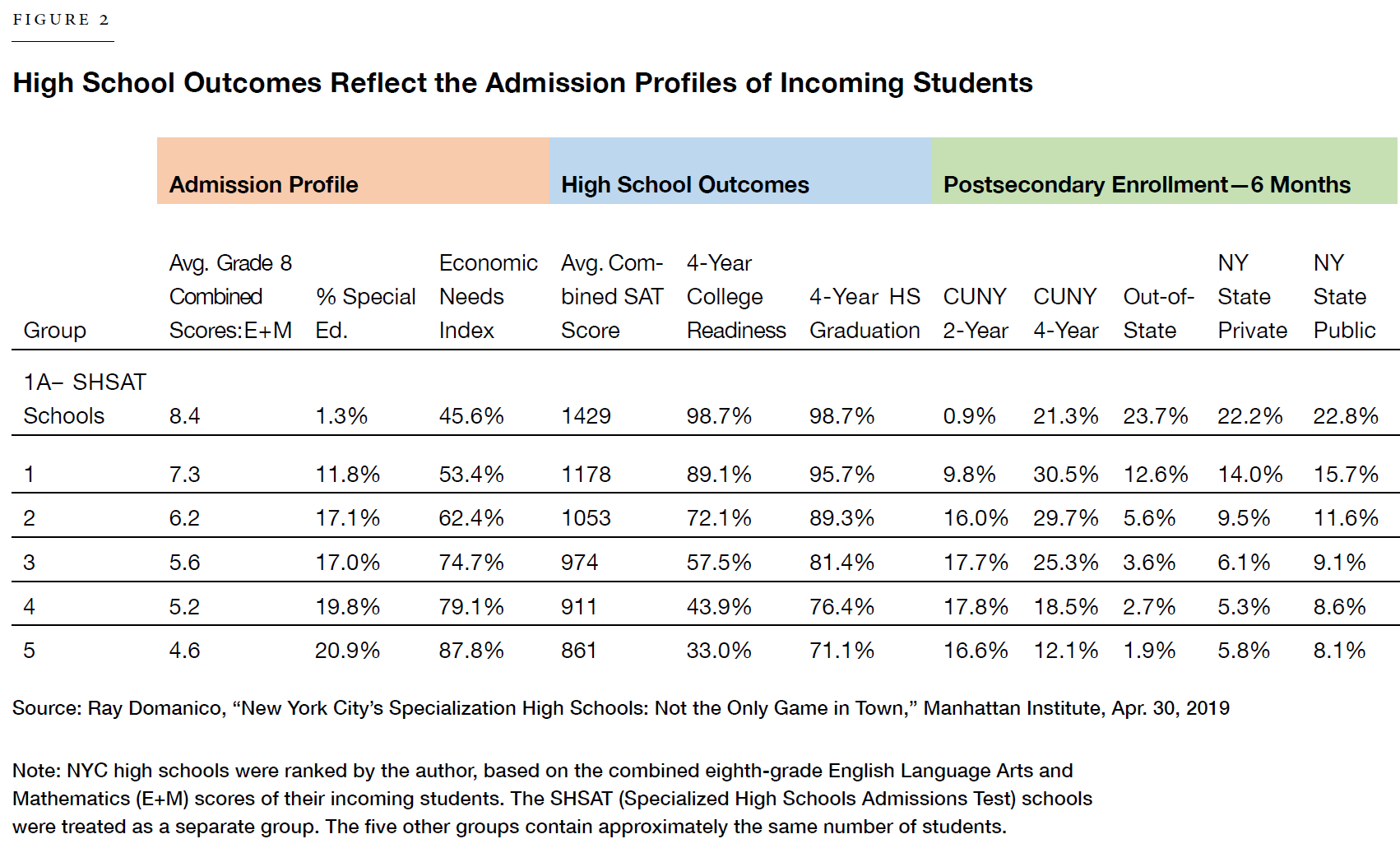

An earlier paper of mine published by the Manhattan Institute demonstrated that the city’s high school outcomes varied greatly across its 419 district high schools, and that variation tracked the academic profile of students before they entered high school. The city’s high schools differ in terms of the preparation of the students who enter them in ninth grade. Those schools that admit the highest-achieving eighth-graders had high school graduation rates averaging better than 90% and college-readiness index scores in the 90s as well. At the other end, schools in the bottom tiers had graduation rates averaging in the mid-70s and college-readiness index scores in the 33%–44% range (Figure 2).[9]

As this current report examines post–high school experiences, it is important to keep in mind that whatever strengths and weaknesses the city’s high school graduates have as they exit high school seem to be more or less predictable from their middle-school performance. To the extent that corrective action is necessary, it may be required at both the high school and college levels.

How Many Graduates Enter the City University?

NYC DOE does follow-up surveys on its graduates six and 18 months after graduation.[10] For the graduates of 2018–19, 23.9% of graduates were enrolled in CUNY’s two-year college programs six months after high school graduation (Figure 3); 21.9% were in CUNY’s four-year programs. These survey results suggest that graduates of the city’s district high schools made up 73% of the total number of first-time freshmen in CUNY’s bachelor’s degree programs in 2019 and 59% of the first-time freshmen in associate’s degree programs.[11] Other public colleges in New York State enrolled 13.6% of the city’s graduates while private colleges within the state enrolled 11.4%. Approximately 7.7% of the graduates were enrolled in colleges outside the state. A little over 19% were not located in any post–high school education or training settings.

A Snapshot of the City University of New York

The CUNY system today operates seven senior colleges, which offer bachelor’s degrees. Seven community colleges offer associate’s degrees. Three comprehensive colleges—the College of Staten Island, Medgar Evers, and NYC Technical College—offer both bachelor’s and associate’s degrees. CUNY prides itself on not only being the largest public university system in the country but also for placing six senior colleges and six community colleges “among the top 10 four-year and two-year colleges nationwide with the greatest success in lifting low-income students into the middle class,” according to a Brookings report that replicated the results of an earlier study by noted economist Raj Chetty.[12]

These findings represent a huge turnaround from 22 years ago, when a mayoral task force headed by former Yale president Benno Schmidt labeled CUNY “an institution adrift.”[13] The task force criticized the loose academic standards at CUNY and urged that the system institute meaningful admissions standards in its three types of colleges: “selective senior colleges” with high standards; “more broadly available senior colleges” with admissions standards assuring that students are capable of college-level work; and community colleges with open admissions for students with the basic skills needed for academic and professional success.

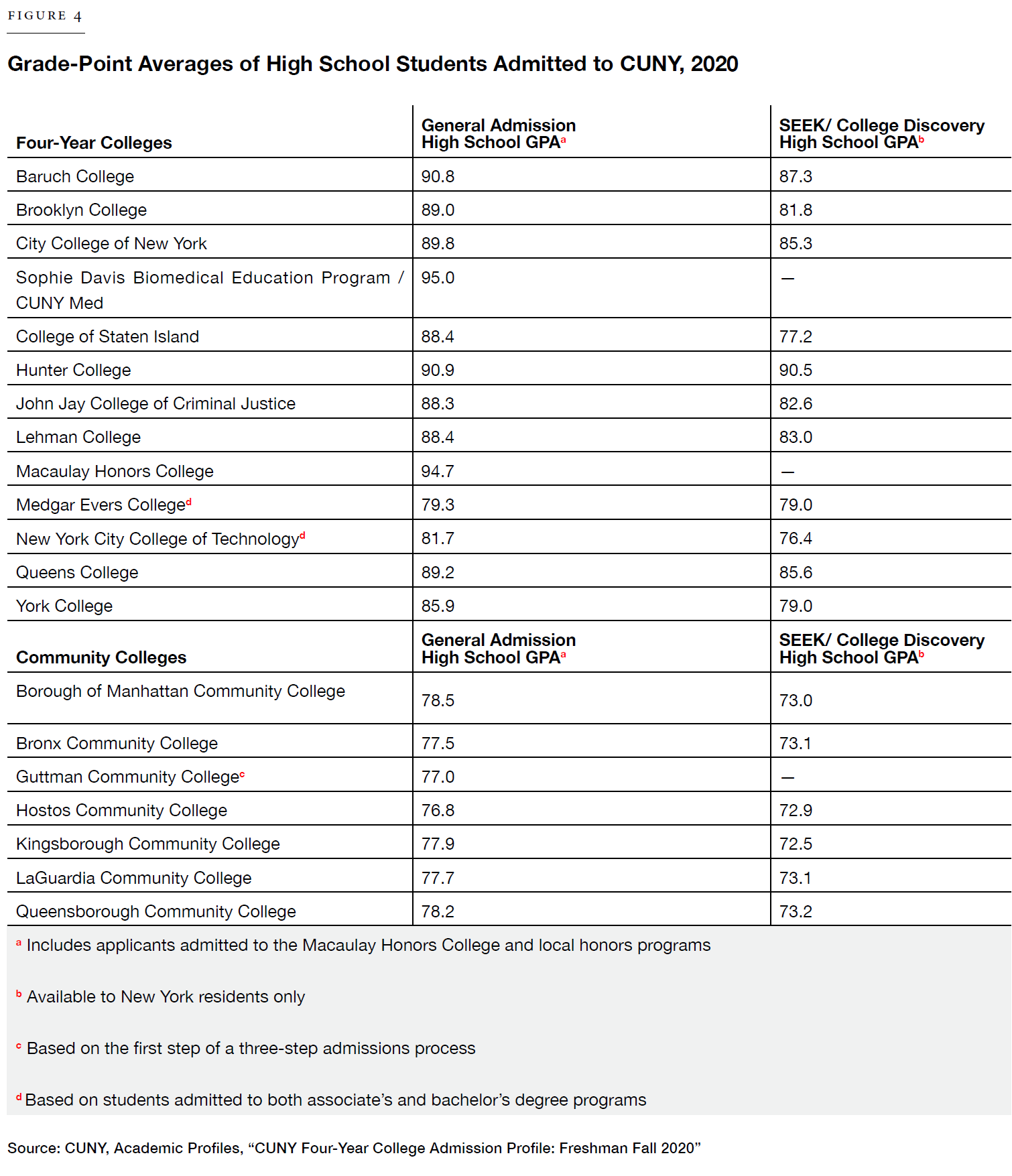

Over the next few years, the guidance to install admissions standards was followed, though perhaps not with the clear demarcation between selective and more broadly available senior colleges. Today’s tiered system of admissions can be seen in Figure 4.

In addition to the Macaulay Honors College, founded in 2001, and the specialized undergraduate biomedical program at the Medical School, five of the older senior colleges—Hunter, Baruch, Brooklyn, Queens, and City—admit a student body with average high school GPAs of 89 or above, except for lower-achieving students admitted through the SEEK or College Discovery programs. The remaining four-year colleges generally admit student bodies with average scores between 79.3 and 88.4. The community colleges all admit student bodies with average high school grades in the 76.8–78.5 range.

Special Programs: College Discovery, SEEK, and ASAP

CUNY operates a number of programs designed to assist students from groups that have been traditionally underrepresented in higher education. College Discovery “provides comprehensive academic, financial, and social supports to assist capable students who otherwise might not be able to attend college due to their educational and financial circumstances.” The Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge (SEEK) is a similar program operating at the senior and comprehensive colleges.[14] The Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) has shown particularly promising results.[15] A rigorous evaluation conducted over seven cohorts of entering students found three-year graduation rates of ASAP students to be more than twice that of students in the comparison group. ASAP provides intensive counseling and requires its participants to meet regular benchmarks in terms of attendance and course completion to remain in the program and to receive “financial resources (tuition waivers for students in receipt of financial aid with a gap need, textbook assistance, and New York City Transit Metro Cards), and structured pathways to support academic momentum (full-time enrollment, block scheduled first-year courses, immediate and continuous enrollment in developmental education, winter and summer course-taking).”[16]

CUNY Outcomes: Retention and Graduation Rates

Graduation rates within CUNY are slightly below the national average. The latest report from the National Student Clearinghouse indicates an overall six-year graduation rate, across two- and four-year colleges combined, of 60.1% for the cohort that entered college in 2014.[17] The rate for four-year public universities was 67.4% nationwide, compared with 60.4% for CUNY’s baccalaureate programs. For CUNY’s associate programs, the attainment of associate’s degrees tends to peak four years after initial enrollment. For the cohort that entered these programs in 2015, the four-year rate was 25.7%. For an earlier cohort that entered college in 2009, the four-year rate was 18.5%, but the 10-year rate was lower—17.3%—as students became reclassified as bachelor’s degree recipients. Overall, after 10 years, 21.3% of students who started in associate programs earned a bachelor’s degree, for a total degree completion rate of 38.6% (Figure 5). The national completion rate after four years for two-year programs stands at 42.1%.

Enrollment Patterns in Associate and Certificate Programs in CUNY

With only about a quarter of the students who enter CUNY’s associate’s degree programs earning an associate’s degree within four years, and 38.6% earning either an associate’s or a bachelor’s degree within 10 years, it is worth reviewing the areas of study that the students in these colleges are pursuing. We know that these students enter college, on average, as high school graduates with grades in the 70s.

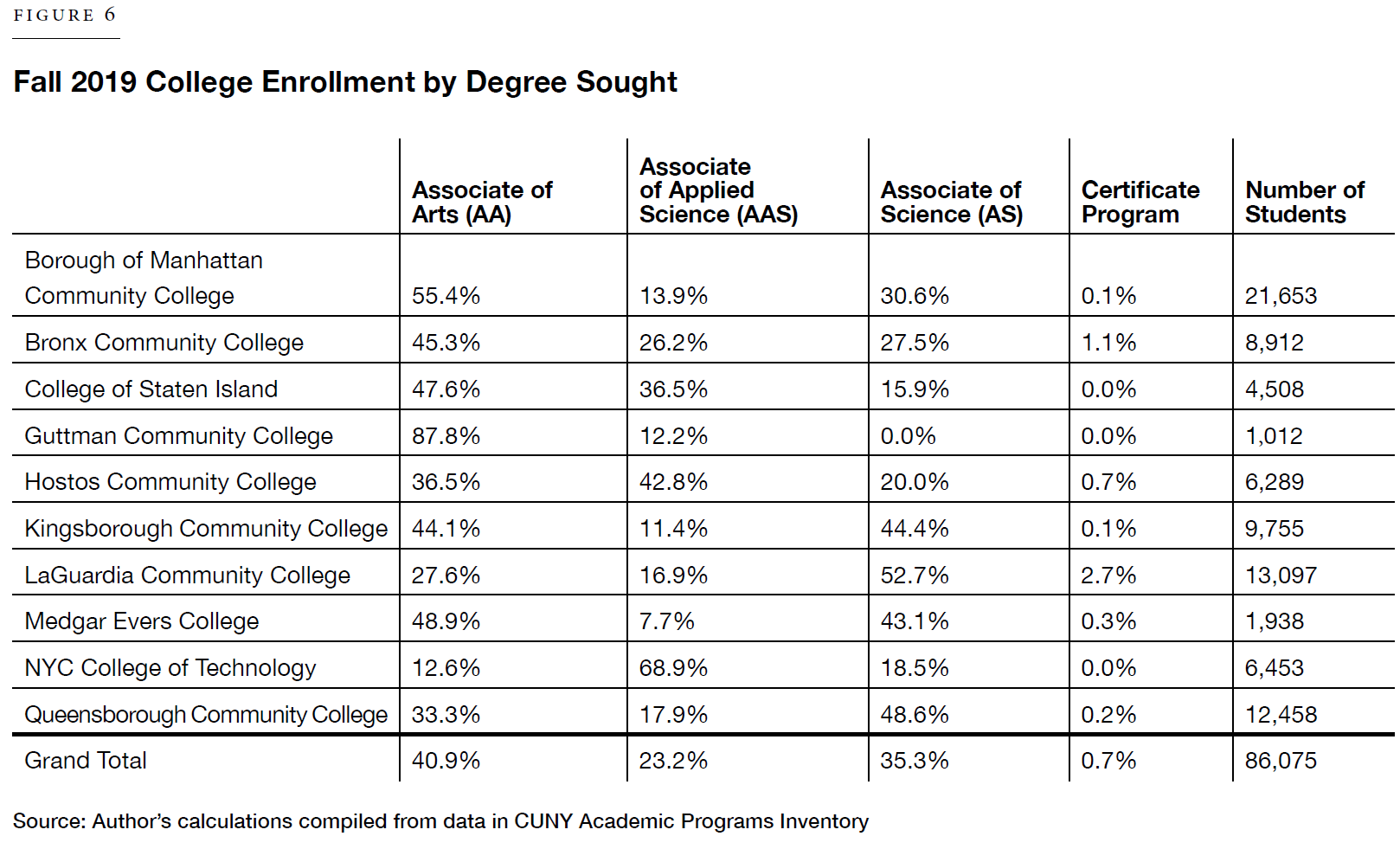

CUNY offers three associate’s degrees, defined by the College Atlas as follows: “The Associate of Applied Science (AAS) is designed for students who intend to enter the workforce immediately following graduation from their program. Alternatively, the Associate of Arts (AA) and Associate of Science (AS) Degrees are designed primarily as transfer degrees.”[18] AA and AS degrees are designed to prepare students for entry into a bachelor’s program upon completion of community college. Certificate programs focus on a single vocational area of study and do not necessarily require two full years of study. They are meant to prepare students for entry into the workforce.

Fewer than a quarter of CUNY’s associate’s degree students are enrolled in either the terminal AAS degree or a certificate program. Two colleges, Hostos (42.8%) and NYC College of Technology (68.9%), stand out for having higher percentages of their students in AAS programs. More than three-quarters of the students in CUNY’s associate’s degree programs are in programs designed to prepare them for entry into bachelor’s programs after attainment of their associate’s degree (Figure 6).

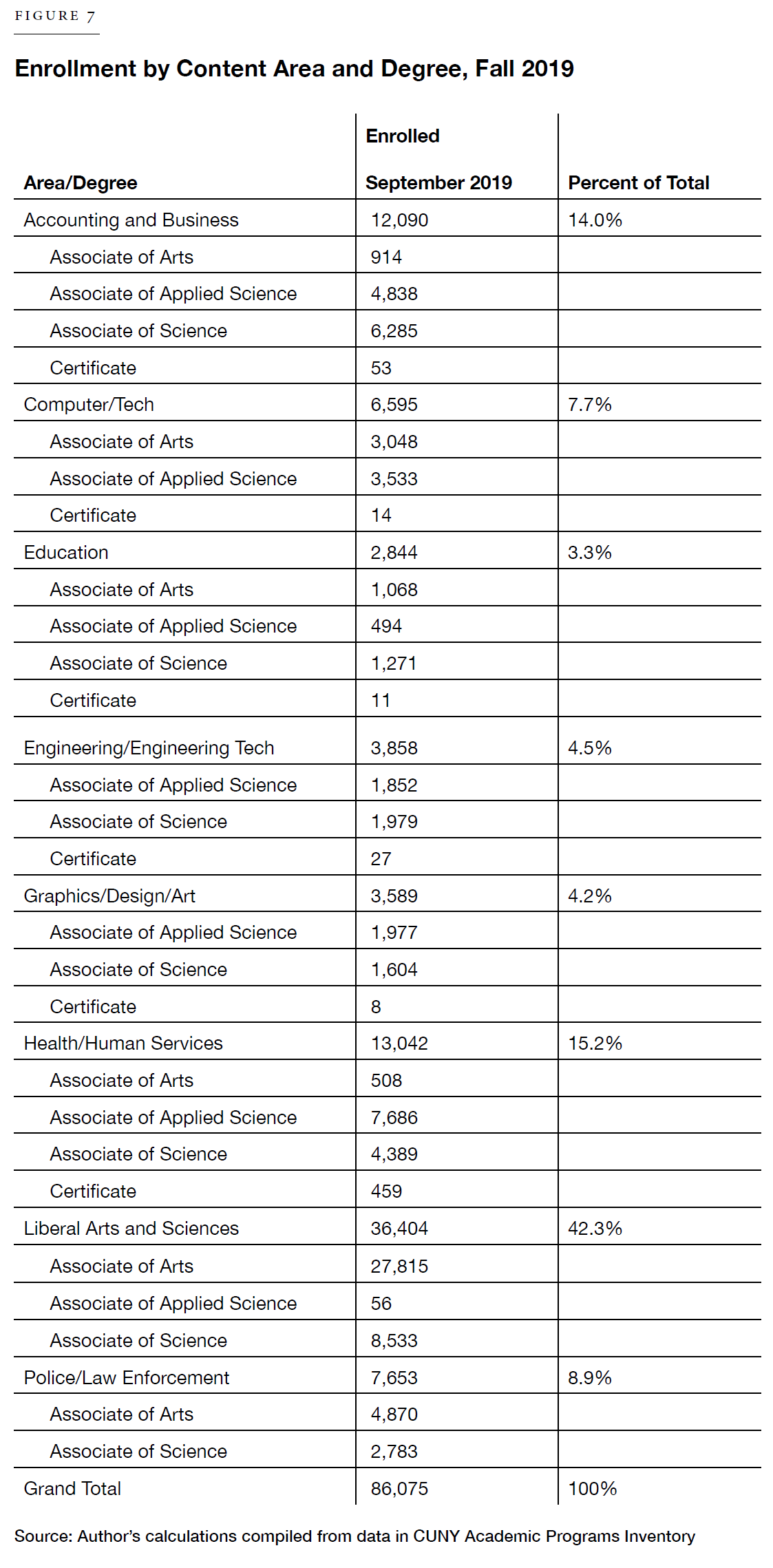

Forty-two percent of CUNY’s associate students are enrolled in liberal arts or science programs, and virtually all of them are enrolled in AA or AS degree programs (Figure 7). Almost 38% of the students enrolled in AAS programs are studying health or human services; an additional 23.7% are in accounting or business programs. Over 40% of AAS students studying accounting or business were enrolled at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, as were 22.7% of AAS students in computer/tech studies. The 62.9% of AAS students in engineering or engineering tech were from New York City Technical College.

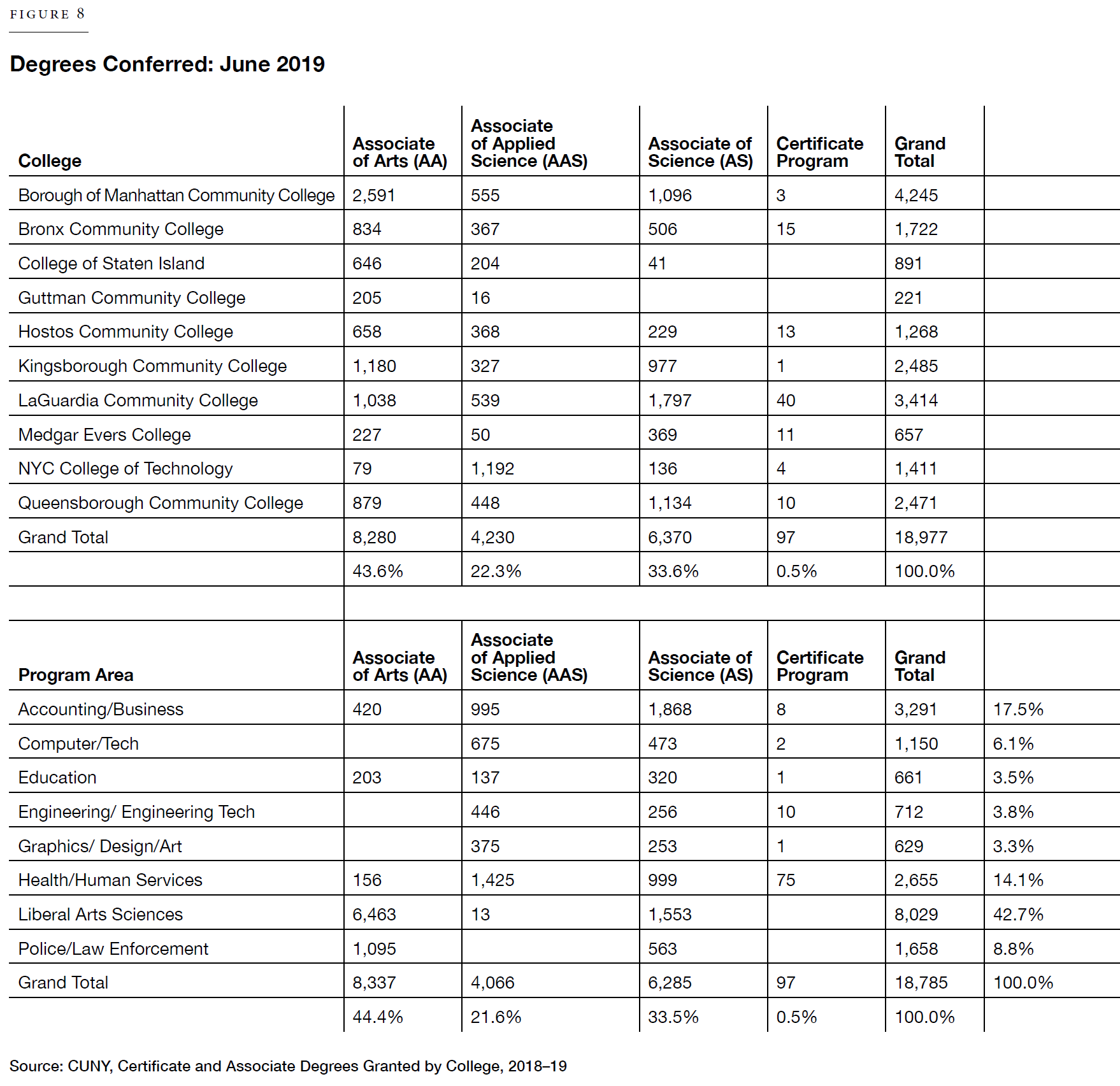

Degree attainment tracks enrollment patterns (Figure 8). Forty-four percent of the degrees conferred in the associate programs in June 2019 were AA degrees, compared with the 40.9% of all students enrolled in AA degree programs. AAS degree programs accounted for 33.5% of graduates and 35.3% of enrollment. The AS programs comprised 21.6% of graduates and 23.2% of enrollment. Fewer than 100 students earned certificates in 2019.

A greater percentage of CUNY’s associate’s degree recipients report that they were employed in an area unrelated to their program of study (35.1%) than reported that their job was directly (13.2%) or slightly (15.4%) related to their program of study six months after graduation (Figure 9). Almost a quarter of the graduates (23.6%) reported that they were unemployed though seeking employment, and 49.3% reported that they were employed full-time. Of those employed, their most common placements were in office and administrative support, health care, education, and food preparation, serving, and hospitality. The reported salaries of graduates were generally low, with only 39.7% reporting salaries at or above $30,000 per year. Generally, graduates felt good about their CUNY education, with 50.8% reporting that they felt well prepared or adequately prepared for their job, while 11.7% reported feeling poorly prepared or very poorly prepared.

Discussion

CUNY has earned well-deserved praise in recent years for taking students from lower-income backgrounds and putting them on the path to financially secure and independent lives. Yet college is not the path for everyone. CUNY’s standing in the nationwide assessment of colleges promoting social mobility does not negate the fact that many students—ill-prepared for college-level work—are still falling through the cracks after pursuing liberal arts degrees. To be sure, this is true of many colleges across the country. Nationwide, college completion rates are 67% for baccalaureate programs (within six years) and 42% for associate programs (within four years). CUNY’s completion rates are 60% for baccalaureate programs and about 25% for associate programs, although 38% of these students earn either an associate’s or a bachelor’s degree within 10 years after entering college.[19]

To some extent, the lower performance of CUNY seems tied to the high school achievement of the city’s high school graduates, who constitute about 73% of CUNY’s entering students in bachelor’s degree programs and 59% of students entering associate’s degree programs. The higher-achieving graduates funnel into the bachelor’s programs, and the associate programs get the less well prepared. Nevertheless, 42% of the students in CUNY’s associate programs are enrolled in liberal arts programs, and an additional 24% are enrolled in other programs designed to prepare them for eventual entry into bachelor’s programs; only 23% are enrolled in terminal AAS programs. Given the low graduation rates of CUNY’s associate’s degree students—25.7%, four years after enrolling—it is reasonable to ask if there is a mismatch between the preparation of students upon entry to these programs and the program placements that they are taking.[20]

A recent summary report from Brookings Institution’s Brown Center emphasizes the importance of comprehensive support services for students in community colleges, given the “many personal and institutional obstacles they face while trying to persist in school. Challenges arise in the form of family responsibilities, health issues, financial shocks, mental health struggles, among others.” The primary example of successful support programs cited by the report is CUNY’s own ASAP program, which independent evaluators have found to be clearly successful in increasing both student retention and graduation rates. Even so, the evidence regarding the effectiveness of “billions of dollars” spent nationwide on remedial programs, according to the report, is discouraging, and further efforts to eliminate tuition for community college students “is unlikely to substantially increase community college completion rates.”[21]

Writing in The 74, longtime education analyst Bruno Manno describes five locally developed programs that seem to be doing a better job of preparing young people for the world of work. “They foster opportunity pluralism, creating new options to the ‘bachelor’s degree or bust’ mindset.” Manno describes their common components as having “a sequenced academic curriculum ... aligned with labor-market needs and a timeline guiding participants through the program; formal agreement among multiple participants; introduction to careers and on-site work experience; and the involvement of employers, trade associations and local organizations.”[22] Agreements among schools, colleges, government agencies, and businesses or trade associations are clearly defined in written agreements with assured access to key decision-makers.[23]

Opportunity America, a think tank headed by Tamar Jacoby, issued a report in 2019 that considered the changing nature of higher education, with many older students and others pursuing their degrees part-time. “Industry Certifications: A Better Bridge from School to Work” noted that “many seek … shorter, more job-focused credentials.” Given the complexity of predicting future labor-market needs in a fast-changing economy, the report emphasizes the importance of employers playing a strong role in the certification process. The typical certification process led by industry associations “canvasses employers from across the sector to create one or more job profiles—detailed lists of the skills workers need, occupation by occupation and job by job. The industry group then translates these job profiles, sometimes called ‘skills standards,’ into assessments—sometimes written, sometimes performance-based.” These tests are then reviewed by testing specialists and field-tested before being put to use. Importantly, they are reviewed and updated regularly. Industry leadership is key: “many certifying bodies cooperate with high schools and colleges that offer programs geared to their assessments. But few depend on educational institutions. Indeed, most make a point of their independence.”[24]

In 2020, Opportunity America convened a panel of experts to consider reimagining the nation’s community colleges as the country rebounds from the Covid-19 pandemic and the world of work appears to have changed for the long term.[25] The final report of this group called for a refocusing of community colleges to strongly accept their role as preparing their students for entry to the workforce. They should be “rooted in the local labor market”; embrace the education of “mid-career adults” offering “more classes, credit and noncredit, in the evenings and on weekends.” Whenever possible, their programs, the report emphasized, “should be offered in partnership with employers who help design the content and stand ready to hire graduates.” These programs need to be judged by their success at job placement: “community college funding should be geared more closely to job placement and wages” and engage in “day-to-day” collaboration with employers.[26]

At the high school level, New York State and NYC have made progress since a 2016 Manhattan Institute report noted the then-slow uptake in technical certificate programs in high schools.[27] Currently, the State Education Department has 74 approved certificate titles in 13 broad areas of work.[28] NYC DOE has increased the number of career and technical education programs to “301 total programs across 135 NYC high schools [that] are now reaching 64,000 students.”[29]

More is needed, particularly at the community college level. In considering ways for NYC to improve the outcomes for those students who begin and end high school lagging behind their peers, elected officials and community leaders need to rethink the current emphasis on the attainment of a bachelor’s degree. Money can be wisely spent on the existing ASAP program to increase college graduation rates, but rethinking the goals of high schools and community colleges is equally important. This effort must not be left to DOE or CUNY; it must involve the city’s employers in traditional as well as emerging industries.

Endnotes

About the Author

Ray Domanico is a senior fellow and director of education policy at the Manhattan Institute. His career has spanned the public and non-profit sectors, in research and advocacy roles. Most recently, Domanico was director of education research at New York City’s Independent Budget Office, where he led a team tasked with studying and reporting on the policies and progress of America’s largest public school system. Previously, he served as senior education advisor to IAF Metro NY where he worked with local leaders and educators to design and support a small group of new district high schools and charter elementary schools. Domanico began his career in research positions in the New York City school system, and he has taught graduate-level courses in educational research and policy analysis at Brooklyn College and at Baruch College.

Domanico holds an MPP (master of public policy) from the University of California, Berkeley.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).