Restoring Public Safety

This paper is part of a series Policy Recommendations to Renew and Reform New York State, adapted from the Empire Center’s The Next New York series.

New York was the site of what was surely one of the most significant government-led achievements in urban American history: a steep drop in serious violent crime, continuing across a 25-year period from the early 1990s well into the second decade of the 21st century.

As of 1990, New York State’s violent crime and murder rates per 100,000 residents had reached 1,180.9 and 14.5, respectively. By 2015, those measures had plummeted to 379.7 and 3.1—respective declines of 68% and 79%. The statewide reduction in criminal violence was concentrated in New York City, which had accounted for nearly 87% of the 2,605 murders reported to the FBI by New York State in 1990. Then as now, violent crime was significantly concentrated within small slices of the city’s neighborhoods, whose black and Latino residents benefitted most from the decline.

As crime plummeted, New York City blossomed. Over the course of a single decade, the once crime-ridden, under-developed city depicted in gritty vigilante and gangster movies—whose northern-most borough was infamously observed in flames by horrified viewers of the 1977 World Series—rebranded itself as the safest big city in America.

In recent years, however, the previously steady decline in violent crime in New York has ground to a halt—and even begun to reverse. An uptick in violent crime, concentrated in the state’s urban centers and accelerating during the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic, constitutes perhaps the most serious challenge for policymakers. Successfully meeting that challenge and addressing those concerns will require an understanding of what lies at the root of the problem.

The Status Quo

New York’s success on the crime-control front coincided with meaningful changes to policing and criminal justice policy. Informed by (1) the insights of the Broken Windows theory advanced by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, and (2) a better understanding of (and a deeper appreciation for) crime data, policing in New York City became more responsive to the concerns of residents regarding both serious crime and quality-of-life offenses.

Led by a bold new commissioner in William J. Bratton, who was appointed by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani in 1993, the New York Police Department also adopted a more aggressive mission aimed at preventing, rather than merely responding to, serious crime. For the first time ever, the NYPD—through its development and use of CompStat, which is now used by police departments around the world—was, in the 1990s, using data to deploy officers, gather intelligence, and measure its effectiveness. Those efforts were boosted when, thanks to the federal Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the department received grant money to facilitate the hiring of new officers, augmenting a build-up funded by the Dinkins-era “Safe Streets, Safe Cities” dedicated tax, as well as the redeployment of officers that had been tasked with clerical and administrative duties.

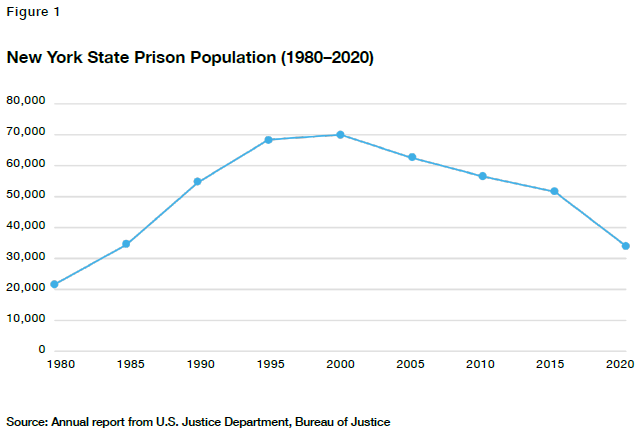

New York’s new approach to policing, which featured tactics like stop, question, and frisk and “flooding the zone” was backed by a broader criminal justice system committed to taking (and keeping) a great many of those arrested and convicted of crimes off the street. That commitment is illustrated by the data on statewide incarcerations, which reflect a sharp upward trend in imprisonment beginning in 1980 and continuing through the year 2000 (see Figure 1, below), which was made possible by a major state prison expansion that started in the 1980s.

That uptick in incarceration was, perhaps not coincidentally, accompanied by sharp declines in violent crime from 1990 to 2000, as shown in Figures 2 and 3.

The more recent increase in crime seems to be a predictable result of criminal justice “reforms” that undermined or even deliberately reversed the successful policies of the 1990s and early 2000s. Restoring public safety will require a reorientation of the criminal justice system around a public safety, rather than a reform-centric, mission. This worked in the past and can work again.

After back-to-back nationwide spikes in homicides in 2015[1] and 2016,[2] many parts of the country saw their public safety pictures deteriorate significantly. New York experienced smaller murder increases those years,[3] but the state (for a time) quickly recovered. Just 547 homicides were reported statewide in 2017 (a 40-year low)—including only 292 in New York City (an all-time low).[4]

Recent research suggests that the post-2010 decline in gun violence that took place in New York City may have been driven in significant part by enforcement efforts that targeted high-risk offenders with an eye toward securing their incapacitation, leading to fewer victimizations in some of the city’s pockets of concentrated crime.[5] Despite that progress, however, New York City would see homicides rise every year from 2018 to 2021. Statewide, murders rose in 2015, 2016, 2018, and 2020. The state’s 2020 homicide spike was 46.7%, which was identical to New York City’s 2020 murder spike.[6] In 2020 and 2021, respectively, Buffalo saw 65 and 67 homicides—significantly more than the 46 homicides the city had averaged between 2015 and 2019.[7] Syracuse recorded its worst year for homicides in 2020,[8] a level repeated in 2021.[9] Albany also has experienced a homicide spike[10] since 2020, a year when shooting incidents in the state’s capital city more than doubled.[11]

NYS Arrest, Conviction, and Incarceration Trends, 2017–21

The sharp downward trendline in the state’s violent crime and homicide rates illustrated by figures 2 and 3 leveled off shortly after the turn of the century; and, in the case of the state’s murder rate, the trendline began to turn upward in the second half of the decade.

The end of what had been a decades-long downward trend in violence was preceded by the start of a sustained downturn in the state’s incarceration rate. After New York’s violent crime numbers plummeted, the state began imprisoning fewer and fewer offenders after 2000. That trend toward decarceration—i.e., reducing the number of people imprisoned—has continued through the time of this writing, as shown in figure 1.

New York’s post-2000 prison decarceration trend followed a decrease in the number of arrests, as well as in the share of arrests resulting in convictions and incarcerations. The decreases seem to be driven in part by a recent upswing in the share of adult arrests resulting in dismissals depicted in Figure 5—to say nothing of the 2020 releases and diversions related to efforts to reduce the spread of Covid-19 in correctional facilities.[12]

The sustained decline in New York’s prison population (persons serving at least one-year sentences for felonies) has been accompanied by a steady decline in the state’s jail populations (persons detained while awaiting trial or serving lesser sentences). Total jail populations in the state have gone from a daily average of 25,000 in 2016 to just over 15,000 in 2021—bottoming out in 2020 at just over 12,600, as shown in Figure 8. As with crime statistics, this statewide decrease trend was driven primarily by trends in New York City.

Change of directions

As New York streets got safer, tolerance for aggressive (and effective) law-enforcement practices began to erode and calls for reforms aimed at addressing “mass incarceration” and “police brutality” grew louder. Those calls informed a movement that grew in strength in the 2010s in New York and throughout the nation in the wake of high-profile examples of the criminal justice system’s excesses—such as the jailing and subsequent suicide of Kalief Browder[13] in New York—as well as cases of alleged police abuses.

After the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer and ensuing riots in many cities in 2020, the national criminal justice and police reform movements went into overdrive. New York was no exception.

Following a surge in crime beginning in the 1960s, changes to criminal justice policies in New York during the final quarter of the 20th century almost uniformly signaled a tougher approach to crime. But the criminal justice “reforms” of the 2000s have run in the opposite direction—easing restrictions and penalties for those suspected and accused of crimes. Collectively and on their own, these more recent changes have undermined policing, prosecution, and public safety.

The bail rollback

In line with the national push among many criminal-justice reform advocates to cut the nation’s incarceration rate (in jail and prison), a push to curtail cash bail with the hope of depopulating the Empire State’s jails gained steam in the mid-2010s—particularly after Browder’s tragic case came to represent the alleged injustices inherent in the state’s pretrial detention policies.[14] Signed into law as a provision of state budget legislation[15] in April of 2019 and taking effect in January 2020, the new bail regime placed new limits on judicial options regarding the release of pretrial defendants.

The legislation drastically shrank the scope of criminal cases in which judges are allowed to require bail or remand defendants to pretrial detention.[16] It also placed limits on the conditions (such as electronic monitoring) that judges can impose on a defendant “who poses a risk of flight to avoid prosecution.” In such cases, the law stipulated, “the court must select the least restrictive alternative and condition or conditions that will reasonably assure the principal’s return to court.” This language thus retained the state’s longstanding prohibition on the judicial consideration of the public safety risk posed by a given defendant when making any decisions related to pretrial release.

New York’s exceptionalism

New York State is the only state imposing a blanket ban on the judicial consideration of dangerousness in all aspects of the pretrial release decision-making process.[17] The law also requires judges to “explain … on the record or in writing” their rationale for imposing conditions on pretrial release, effectively an added hurdle to pretextually imposing high bail amounts in order to secure a defendant’s detention based on perceived risks.

For all intents and purposes, the 2019 changes to bail laws (despite modest amendments in 2020 and 2022[18]) required release on recognizance for all defendants not deemed a flight risk. Bail is now limited to cases involving “qualifying offenses”—almost all of which are high-level felonies involving violence, the threat of violence, or sexual exploitation.

Those exceptions in themselves amount to a tacit admission that dangerousness ultimately does matter, reflecting a glaring incongruity between the law’s plain language and how it is structured.

The impact

As illustrated by Figure 8 above, the primary impact of New York’s bail reform was to reduce the jail population constituted by pretrial defendants. This shift could impact crime primarily through the erosion of two mechanisms through which public safety benefits can be secured: incapacitation and deterrence.

By allowing a larger share of accused criminal defendants to spend the pretrial period on the street, New Yorkers became more vulnerable to crimes committed by this population. Perhaps the most pertinent statistics to illustrate the bail reform’s effect on crime via reduced incapacitation are those regarding the sharp upticks in shares of total arrests and violent felony arrests constituted by offenders with pending cases in the state’s largest city.

In 2019, 19.5% of total arrests and 20.2% of violent felony arrests by the NYPD were of offenders with pending “open” cases. In 2020, those figures jumped to 24.4% and 25.1%, respectively—precisely what one would expect to see if pretrial release reform harmed public safety.[19]

While no analyses of New York’s bail reform law have been done with an eye toward assessing the reform’s impact on deterrence, a large body of research shows that immediacy is one of the most important determinants of a given sanction’s deterrent effect.[20] Given that New York State’s new bail law meant an arrest was much less likely to be accompanied by immediate financial consequences (or a trip to jail), the costs associated with certain criminal activity are likely now perceived to be lower by criminal actors, who, in turn, may be less likely to be deterred by the prospect of an arrest today than they would have been prior to the law’s implementation.

Seeking to minimize the negative impact of the new law, advocates of minimizing bail often cite an Albany Times Union analysis of data released in January 2022 by the state Office of Court Administration and Division of Criminal Justice Services.[21] The main finding: between July 2020 and June 2021, “just two percent of released defendants were rearrested for a violent felony during the pretrial period.”

But that report was flawed and misleading in three crucial respects.

First, the fact that a defendant was not rearrested does not in itself demonstrate that he or she did not commit a new crime, since most crimes are neither reported nor solved.

Second, the report focused on defendants rearrested for violent felonies, but did not count total rearrests of pretrial releasees. In particular, the data did not tabulate rearrests after a defendant’s first rearrest. This would lead to an undercount of violent felonies committed by defendants who had already been rearrested on less serious charges while awaiting trial.

Third, the baseline denominator for the analysis was the total number of defendants released, rather than the subset who might have been detained or subject to more restrictive release standards based on a dangerousness standard.

One such subset is the population of defendants placed in supervised release programs—many of whom, under previous law, might have been detained based on an inability to make bail. In fact, a January 2022 analysis by The City, based on the same state data sources cited in the Times Union report, found that 41% of supervised release program participants were rearrested, with 23% rearrested for a felony.[22]

The new discovery burden

In addition to changing bail laws, other provisions enacted in 2019 significantly elevated the compliance burden for prosecutors by expanding the information that must be shared with defense attorneys as part of the pretrial discovery process, and compressing the time period in which this sharing must take place.[23] Key provisions of the new law require prosecutors to assemble and deliver to defense attorneys 21 types of materials, including:

- names and contact information of all those with information relating to the case, with limited exceptions for confidential informants, members of criminal enterprises, 911 callers, and victims or witnesses of certain sex offenses;

- all relevant electronic recordings (again with very limited exceptions), including body camera footage of responding officers (which prosecutors would first have to review and appropriately redact);

- information regarding any expert witnesses and their qualifications; and

- the results of any relevant scientific or physical tests, examinations, or reports completed by investigators.

New York’s pre-2020 discovery rules only required that materials other than exculpatory evidence be turned over to defense counsel prior to trial—a relatively rare occurrence, given the rate at which criminal cases were disposed of via plea bargains. But under the new law, prosecutors must comply with these requirements within 20 days of arraignment for cases involving defendants detained pretrial, and within 35 days of arraignment for defendants who are released while awaiting trial. Significantly, plea bargains are not allowed until at least three days after discoverable materials have been turned over.

Failure on the part of the prosecution to fully comply with these new discovery burdens can be met with sanctions including a ban on presenting certain evidence, a mistrial, or even case dismissal (which, as shown in Figure 9, has become a more common occurrence since 2020). These new rules could force prosecutors to delay bringing certain cases, or to avoid pressing some charges in light of the additional information-gathering burden, which prosecutors were not given new funding to meet. District attorneys unable to do substantially more with less must simply do less.

Beyond putting more cases in jeopardy, and potentially leaving more offenders on the street, the new discovery provisions have left prosecutors unable to assure witnesses that their cooperation will remain a secret.[24]

Finally, complying with the new discovery rules has drastically increased the amount of time prosecutors must devote to menial “paper-chasing” tasks. This has led to widespread reports of what one New York district attorney called “a marked increase in attrition” among staff.[25]

Leniency for parolees

The “Less Is More: Community Supervision Revocation Reform Act,” signed by Governor Hochul in September 2021, was a response to claims that minor “technical” violations of parole conditions were fueling “mass incarceration”[26] in New York. Specifically, that (1) when parolees commit a minor infraction of the conditions of their paroles—such as missing an appointment with a parole officer or failing a drug test—they are too often reincarcerated; and (2) those incarcerations are costly, unnecessary for public safety, and racially inequitable.

Evidence from other jurisdictions, including the federal system,[27] suggests why policymakers should have been more skeptical of such claims by illustrating that many violators who had their releases revoked (i.e., who were sent back to prison) had, in fact, racked up multiple “technical” infractions prior to revocation, were charged with new crimes that triggered the enforcement of a violation, or chose incarceration over an alternative such as drug treatment.[28]

Without seeking to carefully document advocates’ claims, state lawmakers heeded calls for drastic changes to how parole conditions are enforced in New York.[29] The Less Is More Act made three particularly dramatic revisions to prior law. First, it drastically limited the availability of reincarceration as a sanction for “technical” violations. Second, it limited the state’s ability to detain even those accused of both “technical” and criminal violations to only those cases in which (in the case of “technical” violators) the violators abscond or (in the case of criminal violators) are found by a judge to pose a risk of absconding—in essence, incorporating the same “least restrictive means” standard featured in bail law changes. Third, the Act raised the bar the state must clear to revoke a convicted criminal’s parole.[30]

More risk

As with the state’s bail reform, Less Is More risks the public’s safety by increasing the population of offenders likely to commit new crimes on the street. This risk is illustrated by national data presented in a Bureau of Justice Statistics study of violent felons convicted in America’s 75 largest counties between 1990–2002, which found that 8% of the felons captured by the analysis were out on parole at the time of the violent felony offenses for which they were convicted.[31] In New York City, a 2011 analysis by the Center for Court Innovation found that 53% of parolees were rearrested at least once over a three-year period, and 42% were reconvicted.[32]

Further illustrating the public safety risk posed by this measure, data highlighted in a Manhattan Institute report show that parolees are more likely than defendants not on parole to be rearrested following a release without bail.[33] The same data also show that parolees were 1.7 times as likely as non-parolees to be rearrested for a violent felony.

The extent of the added risk created by Less Is More is highlighted by state data showing that, between September 2021 and October 2022, the number of technical parole violators in New York State jails on any given day decreased by more than 70%, or 500 parolees.[34]

Other challenges

While the changes to bail, discovery, and parole enforcement laws may have had the greatest impact on public safety, they are by no means the only “reforms” to have recently and systematically lowered the transaction costs of criminal conduct while raising the transaction costs of law enforcement.

The state “Raise The Age” law, passed in 2017, made it more difficult to charge certain teenage criminal offenders as adults, thereby making it less likely that even the most serious violent crimes will lead to lengthy terms of incarceration when committed by 16 and 17 year-olds. A recent study done by the New York City Criminal Justice Agency found significantly higher rates of rearrest for teenagers eligible for youthful offender treatment under the new law, compared to similarly situated defendants prior to the law going into effect.[35]

In 2009, the state revamped the so-called Rockefeller Drug Laws, lowering penalties for certain drug offenses and sharply increasing the rate of diversion for eligible defendants.[36]

And in 2020, Governor Cuomo signed into law a package of 10 bills affecting police practices, tactics, and conduct. Among other things, the package gave the state Attorney General the ability to prosecute officers in certain cases involving fatal uses of force, publicized police disciplinary records (including unsubstantiated allegations), and made the application of “chokeholds” by police a felony offense, punishable by up to 15 years in prison.[37]

But changes to state law don’t tell the whole story, given that many cities within the state have enacted reforms of their own.

In New York City, there was a sharp curtailment of the police tactic known as “stop, question, and frisk,” which research had linked to reduced offending in the city’s pockets of concentrated crime.[38]

The City Council passed legislation mandating the ultimate closing of its jails on Rikers Island, as well as the creation of a new borough-based jail system with a maximum capacity of 3,300—40% below the already reduced average daily population in New York City jails in 2021.[39]

The Council has also approved a host of other local laws affecting police activity, including the Right to Know Act[40] (requiring officers to affirmatively apprise those they contact of their right to refuse consent to a search), a workaround to the legal defense of qualified immunity for police officers,[41] and the so-called “diaphragm bill,” criminalizing the placement of pressure on the diaphragm, neck, back, or chest of a suspect being arrested by police.[42]

Coupled with the election of progressive prosecutors in Manhattan[43] and Brooklyn[44] who have explicitly oriented their office’s policies toward decarceration, all of the reforms discussed above have either favored those who have committed or been accused of crimes or have disfavored those charged with enforcing the law.

Moving Forward

Reestablishing order and safety on New York State streets will require decisive action on the following urgent priorities:

- Make public safety the central concern of pretrial release decisions.[45] This effort must begin by explicitly authorizing judges to remand defendants to pretrial detention on the basis of the risks those defendants pose to the public. Such determinations can and should be aided by a validated, algorithmic risk-assessment tool of the sort already in use in New York City to determine risk of flight. Next, judges should be given the discretion to revoke the releases and amend the release conditions of defendants rearrested while on pretrial release. This could be buttressed by the creation of a rebuttable presumption of pretrial detention for defendants with a history of reoffending while on pretrial release, as well as those accused of certain offenses. Finally, because the bail debate is largely a function of how long defendants stand to spend in pretrial detention, and the potential length of detention for those remanded pretrial is almost entirely a function of resources available to prosecutors, consideration should be given to a large-scale funding effort aimed explicitly at facilitating the more-speedy disposition of criminal cases in New York State.

- Restore balance in criminal prosecutions. District attorneys agree the new discovery rules for criminal cases went too far.[46] Among the more general changes that should be considered are:

- limiting the materials that must be acquired and turned over prior to the setting of a trial date, while maintaining a requirement for the immediate disclosure of any exculpatory evidence the state has knowledge or possession of;

- lifting or loosening the limits on plea bargaining prior to full compliance with current disclosure rules;

- funding the hiring of more administrative staff to assist with compliance with discovery rules; and

- expanding the timeframe for compliance.

- limiting the materials that must be acquired and turned over prior to the setting of a trial date, while maintaining a requirement for the immediate disclosure of any exculpatory evidence the state has knowledge or possession of;

- Mitigate the unintended, if predictable, consequences of “Less Is More.”[47] As in the case of pretrial release decisions, judges in New York must be given the discretion to remand to detention any parolee accused of a violation found to pose a threat to public safety. A reform effort should focus on re-examining the evidentiary burdens with respect to parole violations and subsequent revocations, minimizing the trauma for victims of parolees charged with committing new crimes, and fortifying the ability of corrections officials to properly enforce parole violations.

In addition to these proposals aimed at specifically addressing the heightened risks created by changes to criminal procedure laws since 2019, the following general steps would help fortify New York against resurgent crime:

- Adopt a determinant sentencing regime for cases involving repeat offenders minimum sentences as felony prosecutions that lead to convictions mount;

- Revise the state’s “Raise The Age” law to restore a presumption of prosecution as an adult in criminal court in cases involving 16 and 17-year-old offenders charged with certain gun-related and violent offenses, or with conduct engaged in as part of a criminal enterprise (i.e., gang); and

- Fund additional police hires and training programs with an eye toward attracting and retaining more highly educated recruits.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).