Renewable Term Health Insurance Better Coverage Than Obamacare

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was designed to fund health insurance for individuals who have preexisting medical conditions, by requiring insurers to overprice insurance for people who sign up before they get sick. This feature has made health plans on the individual market a very poor value for most low- and medium-risk Americans—causing millions to abandon coverage, premiums to soar, deductibles to spike, and insurers to flee the market. This feature is also unnecessary because the ACA provides billions in public funds to subsidize premiums, and these subsidies automatically expand to guarantee coverage for those with preexisting conditions.

Short-Term Limited-Duration Insurance (STLDI), which is exempt from ACA rules, survived as a viable competitive market, offering health coverage priced in proportion to individuals’ risks. A recent regulatory reform has extended the permitted duration of STLDI policies, to protect enrollees from deductibles being reset every three months and to allow insurers to guarantee that enrollees’ premiums will not spike if they develop major medical conditions.

STLDI has been disparaged as “junk insurance” that fails to cover adequate provider networks, offers only catastrophic coverage, makes essential benefits unavailable, helps only young and healthy individuals, undermines protections for those with preexisting conditions, and causes premiums for plans on the ACA’s exchange to soar. This study of the STLDI market finds that each of these claims is false.

- For equivalent insurance protection, the premiums for STLDI plans are lower than—in some cases, almost half the cost of—premiums on the exchange.

- The savings to be gained from switching to STLDI are greater for the purchase of more comprehensive insurance coverage.

- While narrow-network HMOs are often the only plans available through the ACA exchange, STLDI plans tend to be PPOs that offer broader access to providers.

- Even smokers in their sixties may find lower premiums for STLDI plans.

- STLDI plans that cover all the ACA’s essential health benefits are widely available, with the sole exception of maternity services.

- Insurers estimate that STLDI deregulation will increase ACA exchange premiums for those who are ineligible for premium subsidies by an average of less than 1%.

STLDI plans cover a significantly larger share of medical costs than ACA exchange plans for the same premiums, and their availability will reduce the number of Americans without health insurance. Restricting good, affordable insurance for people who purchase plans before they get sick is not the way to strengthen assistance for those who are already seriously ill.

ACA and the Individual Health-Insurance Market

In his 2008 campaign for the White House, Barack Obama pledged to guarantee “affordable, universal health care for every single American” and to “lower premiums by up to $2,500 for a typical family per year.”[1] And with the support of large Democratic majorities in both chambers of Congress, President Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) into law on March 23, 2010.

Prior to the ACA, 44 million people (15% of the U.S. population) were uninsured, of which 32 million had been without coverage for more than a year.[2] One study estimated that 18% of applications to purchase health-insurance coverage prior to the implementation of the ACA were denied for reasons of preexisting conditions.[3]

The ACA sought to address this issue by requiring insurers on the individual market to sell coverage at the same price and terms to demographically similar potential enrollees, regardless of their expected medical costs. The intention was to enable insurers to cover the expected high medical expenses of individuals with preexisting conditions, by artificially inflating their profits from enrollees who buy insurance before they get sick. Mark Pauly of the University of Pennsylvania, an economist who did much to define the study of health-insurance markets, deemed this approach “the worst possible way to do a good thing.”[4]

As insurers were required to set premiums before knowing the average medical needs of their enrollees, they initially tended to undershoot—often forcing themselves or their competitors into financial difficulty. After some of the largest insurers fled the individual market, the few remaining hiked premiums to survive—causing prices to spiral upward as the pool of enrollees remaining became sicker. Although the ACA redistributed funds from plans enrolling disproportionately low-risk individuals in order to subsidize plans attracting high-risk enrollees, this failed to remedy the problem, since all plans attracted and retained predominantly costly enrollees.

This new situation compelled insurers to set premiums for plans available through the ACA exchange at levels well above the health-care costs that most people expect to incur—making the purchase of plans unattractive to those without substantial cost-sharing subsidies in all but the sickest cases. Premiums on the ACA-regulated individual market soared 105% from 2013 to 2017.[5] The upshot: while working-age Americans incur annual median health-care costs of $709, the ACA’s benchmark silver plans in 2018 had premiums averaging $5,772 and deductibles typically exceeding $3,900.[6]

The ACA’s architects imagined that these pricing rules would not encourage people to wait until they got sick to purchase insurance, because the rules restricted individuals to buying insurance during annual “open enrollment periods” and penalized those who went without insurance. Yet patients’ broad risk for the most expensive medical conditions, such as diabetes or heart disease, tends to be clear to them ex ante from year to year, so this rule did not spur younger, healthier individuals to sign up. Nor did the “individual mandate” penalty on the uninsured prove effective at driving individuals to purchase plans priced over $5,000 from the ACA’s exchange. Americans without employer-sponsored insurance constitute a relatively low-income group of the population as a whole: 23 million of the 30 million uninsured in 2016 were altogether exempt from the penalty, while only 1.2 million earning above the subsidy cutoff were subject to a tax exceeding $1,000.[7]

The central flaw of the ACA’s insurance-market reforms consisted of conflating two entirely distinct functions: protection for healthy people against the costs associated with the risk that they may get sick; and the financing of services for people who are already sick and in need of support. The former is insurance and an actuarial product; the latter is essentially an entitlement.

Markets function well when sellers who want to sell compete for buyers who want to buy. Under the ACA, policymakers forced insurers to sell plans to people they can’t profitably insure, and then attempted to force other people to purchase overpriced insurance that they didn’t want to buy. Rather than a marketplace in which sellers innovate and compete to attract new customers, the ACA established a scheme in which monopoly status is needed to induce insurers to participate, and for which demand would collapse entirely in the absence of public subsidies. In the fall of 2016, as insurers filed their plans for the following year, 1,036 of the 3,007 counties in the U.S. had only a single insurer willing to sell coverage on the exchange.[8]

While the ACA exchange has proved dysfunctional as insurance, it has functioned relatively well if understood as an entitlement for low- and middle-income households eligible for premium subsidies and a source of catastrophic, safety-net coverage for those with major chronic conditions. Under the law, tax credits automatically expand to the level needed to guarantee coverage at a limited premium for those earning up to 400% of the federal poverty level—$48,560 for individuals, or $96,400 for a family of four in 2018. This population has been largely unaffected by the turmoil experienced in the rest of the marketplace. Furthermore, these subsidies have served indirectly to fund coverage for unsubsidized individuals, by paying greatly in excess of the expected health-care costs for healthy individuals who are subsidized. In 2017, 13.4 million individuals were enrolled in ACA-compliant, non-group plans, and 8.2 million of them were subsidized.[9]

Nevertheless, there remained a great need to reestablish a well-functioning insurance market, capable of offering health-care coverage at prices in reasonable proportion to medical risks faced by most individuals who are uncovered by employer-sponsored insurance or ineligible for public entitlement programs. The Short-Term Limited Duration Insurance (STLDI) market provides a base for the development of such insurance.

A Short History of STLDI

In restructuring health insurance, the ACA adopted the existing legal definition of the individual market, as defined in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). That law sought to guarantee the right of individuals to renew their insurance plans without facing premium hikes as a result of developing major medical conditions. HIPAA specifically excluded STLDI from its renewability requirements—creating a product category outside the individual market that was initially attractive only as a source of temporary coverage for individuals moving between jobs.[10]

When regulations implementing HIPAA were established in 1997, STLDI was defined as “health insurance coverage provided pursuant to a contract with an issuer that has an expiration date … that is less than 12 months.”[11] Other than with respect to HIPAA’s renewal regulations, STLDI plans operated like “major medical” insurance in covering comprehensive health-care benefits, and were subject to the same insurance regulations that, at the time, were otherwise exclusively promulgated and enforced at the state level.[12]

However, as the ACA’s regulations caused premiums on the individual market to soar, STLDI plans became the most attractive source of affordable health insurance for many low- and medium-risk individuals ineligible for federal subsidies. Major insurers including Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare began to offer STLDI. Enrollment in STLDI plans rose by 121% from 2012 to 2016, even though higher-income STLDI enrollees were still subject to the individual mandate penalty for failure to purchase ACA-compliant plans.[13]

Although STLDI enrollment still stood at only 1% of the size of the individual market, the Obama administration cast blame on STLDI plans for the ACA’s rising premiums—arguing that growing STLDI enrollment threatened the ability of ACA plans to profitably cover those with preexisting conditions.[14] On October 31, 2016, with the presidential election a week away, the administration proposed to replace the 20-year-old definition of STLDI plans with a new rule, intended to make STLDI unappealing as an alternative to ACA plans. The new regulation restricted the duration of STLDI plans to three months and prohibited insurers from guaranteeing terms of renewal to enrollees who developed a major preexisting condition.[15]

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) opposed this rule, arguing that it would serve only to send people who got sick within three months to the ACA’s exchange, while healthy enrollees could still purchase STLDI plans afresh. NAIC also criticized the Obama administration for failing to provide any data to substantiate its claims that restricting STLDI plans would serve to ameliorate the ACA market. The restrictions, according to NAIC, would have “little positive impact on the risk pools in the long run.”[16]

The dysfunctional individual insurance market helped contribute to the election of Donald Trump in 2016.17 Yet the subsequent 115th Congress was unable to enact any comprehensive reform of the ACA. In an op-ed, I suggested that the Trump administration restore the STLDI definition to what it was when the ACA was enacted and to waive the individual mandate penalty for enrollees. This would make affordable health insurance available to those who had been priced out of ACA plans.[18] Fourteen U.S. senators endorsed this recommendation in a letter to the new administration, and President Trump issued an executive order on October 21, 2017, calling for revised regulations to allow STLDI plans “to cover longer periods and be renewed by the consumer.”[19]

In the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, Congress zeroed out the individual mandate tax, knowing that it would eliminate the penalty for individuals wishing to switch from ACA to STLDI coverage.[20] An administrative rule deregulating STLDI plans went into effect on October 2, 2018. It allowed plans to be offered with terms of up to a year before deductibles are reset, and it permitted insurers to guarantee that there would be no premium increases associated with medical underwriting for up to 36 months. The rule also required STLDI plans to warn enrollees of the potential absence of mandatory ACA benefits, exclusions of preexisting conditions, and potential dollar limits on coverage.[21]

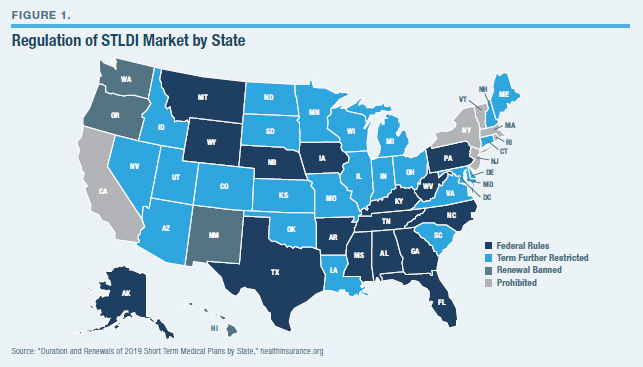

STLDI plans nevertheless remain subject to additional laws, regulations, license restrictions, and taxes that states may impose. Some states have reinstituted the Obama administration’s restrictions on term lengths, imposed ACA-style pricing regulations on the STLDI market, banned reenrollment, and even prohibited the sale of STLDI plans entirely (Figure 1). Conversely, other states have required insurers to guarantee renewability of STLDI plans, and some could allow or even mandate the purchase of stand-alone contracts to guarantee renewability of STLDI plans beyond the three-year federal limit.[22]

Both chambers of Congress are currently considering legislation on STLDI plans. Sen. John Barrasso (R., Wyoming) has sponsored legislation that would strengthen protections for consumers in STLDI plans by extending HIPAA’s guaranteed renewability requirements to them, while Rep. Kathy Castor (D., Florida) has proposed a bill that would reinstitute the Obama administration’s 2016 rule.[23]

Advantages of STLDI Deregulation

In his attempts to sell the ACA, President Obama assured Americans at least 37 times that “if you like your health care plan, you can keep it.”[24] The deregulation of STLDI plans restores the option of affordable insurance plans, priced in proportion to individuals’ health-care risks, similar to those that were sidelined by the ACA.

STLDI plans allow people to purchase more insurance protection for much lower premiums than can be found on the ACA’s exchange. This is primarily because STLDI plans are exempt from the ACA’s “community-rating” regulations—which require that premiums be set at the same level for all enrollees in the same broad demographic category regardless of their expected health-care costs. As a result, STLDI plans can be priced at levels that appeal to individuals who have low or average medical risks, rather than just those with major preexisting conditions.

This also allows the market to be more competitive, as regulators do not need to protect the ability of insurers to run up profits on healthy enrollees to cross-subsidize the much higher health-care costs of those who sign up after they get sick. Nor is there any need for regulatory micromanagement of plan designs, provider networks, and marketing arrangements to prevent insurers from avoiding enrollees of unwanted risk profiles—regulations that tend to become shaped by provider interest group lobbying and serve to cripple cost-control mechanisms.[25]

Furthermore, being able to underwrite premiums enables insurers to viably insure even a small number of enrollees, regardless of who else is in the risk pool—a feature that permits even minor markets to accommodate multiple competing insurers. It also makes it possible to allow individuals to enroll in any plan at any point during the year, rather than being limited to a limited set of permitted benefit options available only in a brief enrollment window.

The individual market has long been a relatively short-term market, covering people who are often between jobs or stable sources of employer-sponsored insurance.[26] The flexibility of STLDI coverage options allows people to purchase plan designs that are more tailored to their individual insurance needs, rather than forcing them to over-insure or under-insure for the benefit of balancing a risk pool.

The existence of employer-sponsored insurance, age-rating bands permitted on the exchange, the right of adults under the age of 26 to enroll on parents’ insurance, and the long-standing broad exemptions from the mandate have always constrained the capacity of ACA regulations to cross-subsidize those with the highest medical risks. Few low-risk people remain willing to overpay, year after year, for ACA plans that offer merely catastrophic coverage.

There are other benefits that result from the 2018 deregulation: individuals with STLDI plans who would otherwise go without insurance can reduce the burden of uncompensated care on hospitals. The availability of these plans may reduce the risk involved in moving from one job to search for another.[27] This particular risk is further reduced by allowing STLDI insurers to guarantee that they will not refuse extensions of coverage or increase premiums to those who develop major conditions during their plan terms.

Only 5% of the American population has high-cost preexisting conditions, which Mark Pauly defined as those with expected annual health-care spending more than double the average for their age.[28] The proportion of these who are uninsurable at the moment they shift from employer-sponsored insurance to the individual market is even smaller. This implies that the share of the American population with preexisting conditions that cannot be affordably insured under STLDI rules is likely to be discrete and very limited.

In any event, allowing people to shift out of ACA plans to less costly, unsubsidized STLDI plans permits the $55 billion in annual public subsidies for exchange plans to be better-focused on the small minority of the population that is genuinely uninsurable.[29] It also makes financing subsidies for those on the exchange more equitable, by ensuring that it is raised by general revenues, rather than a regulatory tax on the purchase of insurance by the disproportionately low-income group that lacks employer-sponsored coverage. By allowing unsubsidized people to buy more affordable coverage through STLDI, the share of ACA exchange enrollees whose coverage is underwritten by public subsidies would increase, and hence reduce the instability and vulnerability of the exchange to premiums that fluctuate according to the vagaries of the enrollee risk pool.

Criticisms of STLDI

House Energy and Commerce Committee chairman Frank Pallone (D., New Jersey), the leading congressional Democrat with jurisdiction over health care, recently launched an investigation of STLDI coverage options, deeming them “junk health insurance plans” and part of “ACA sabotage.”[30] At a hearing for a bill to restrict access to STLDI plans, Pallone listed an array of concerns: “They discriminate against people with preexisting conditions. They set higher premiums for people based on age, gender, and health status. They deny access to basic benefits like prescription drugs, maternity care, and mental health and substance abuse treatment. And they set arbitrary dollar limits for health-care services, leading to huge surprise bills for consumers. Expanding these junk plans also makes health insurance more expensive for people with preexisting conditions, by undermining the market for comprehensive coverage.”[31]

Much criticism of STLDI plans has focused on the most popular coverage options that violate ACA rules. For instance, the Commonwealth Fund has noted that the best-selling short-term plans “exclude four categories of [the ACA’s list of 10] essential health benefits: preventive services, maternity care, mental health and substance use services, and prescription drugs.” It added that these plans “have out-of-pocket maximums ranging from $7,000 to $20,000 for just three months of coverage.” As insurers may be able to rescind coverage if individuals misrepresented their medical history when applying for coverage, Commonwealth suggested that “insurers may comb through members’ medical histories to determine if a service was for a preexisting condition in order to deny a claim.” In sum, “short-term plans are only an option for healthy people.”[32]

A state insurance commissioner invited to testify by Pallone suggested that STLDI plans threaten enrollees with inadequate provider networks, which fall short of expectations, and under-reimbursement for the cost of medical services, which leaves patients paying the balance out-of-pocket. If plans are inadequately constrained by regulators, she suggested, patients may face dollar limits on covered benefits or excessively broad exclusions of preexisting conditions. Comparing the 67% average Medical Loss Ratio (the percentage of an insurance plan’s premium that is spent on medical expenses and related activities for patient care) of STLDI coverage with the 80% ratio for ACA plans, the commissioner argued furthermore that STLDI plans’ relatively high administrative costs made them poor value for money.[33]

Pallone has further suggested that consumers may be misled by insurance brokers into believing that plans cover more than they in fact do, or denied coverage that ought to be covered under contract terms.[34] Others have expressed concern that states lacked sufficient time to change their regulations before loosened federal rules went into effect.

Concern that allowing STLDI plans would harm the ACA market has been widespread. The Commonwealth Fund summarized this belief by suggesting that STLDI plans would “siphon healthy individuals away from traditional health insurance, resulting in a sicker risk pool in the individual market, driving up premiums, and putting the individual insurance market at risk.”[35]

When the proposed rule deregulating the STLDI market was issued, 335 of 340 official comments filed by health-care industry lobbyists were opposed.[36] The health-insurance industry was itself divided: while Aetna and United supported the rule, Blue Cross and Centene were opposed.[37]

Comparing STLDI and ACA Plans

In discussing the new rule expanding the availability of STLDI plans, HHS secretary Alex Azar acknowledged that they weren’t for everyone.[38] The same is true of ACA plans, which were designed primarily around the needs of those with preexisting conditions. It therefore makes sense to compare the two types of plans for different categories of enrollees.

Most existing assessments of STLDI coverage have compared average premiums and deductibles with the ACA market. But this is generally misleading because it fails to control for differences in potential enrollees, risk preferences, and provider networks. Systematic differences between plans are easily obscured by broad averages, and comprehensive, detailed data on the STLDI market are generally unavailable. Evaluations of STLDI coverage relative to ACA plans have often also been skewed by the comparison of yearlong coverage with part-year coverage, whose deductibles must be reset every few months, as was required under the Obama administration’s 2016 rule—a rule that no longer exists.

ACA plans are distinguished from STLDI plans by certain core consistent features—most significantly, community rating. A more accurate understanding of the differences between STLDI and ACA plans can therefore be gained by comparing equivalent typical plans similarly available in the same market.

Fulton County, Georgia (Atlanta), is a good insurance market for this kind of comparison. ACA premiums are close to the national average; several insurers compete on the ACA exchange; and yearlong STLDI coverage is available.[39] Blue Cross (ACA) and UnitedHealthcare (STLDI) plans offered in Fulton County are representative of the major carriers most enthusiastic about each kind of health plan.

For purposes of comparison, ACA premiums for the Blue Cross Bronze plan (covering 60% of medical expenses) and Silver plan (covering 70% of medical expenses) were chosen. UnitedHealthcare’s Short Term Medical Plus Select A plans with benefit structures, deductibles, and out-of-pocket caps most similar to these Blue Cross plan terms were then examined for 360-day and 90-day terms, respectively, reflecting the traditional STLDI maximum term length and that under the 2016 rule.[40] Coinsurance (the share of expenditures between the deductible and the out-of-pocket maximum, which must be paid for out-of-pocket) was 20% for all ACA and STLDI plans examined.

It is generally understood that STLDI plans are more attractive than ACA plans for those who are young and healthy and seeking catastrophic coverage.[41] This intuition is borne out by the comparison of plans for a 30-year-old male nonsmoker in Fulton County (Figure 2). The Blue Cross Bronze ACA plan, with a $7,900 out-of-pocket limit and a $5,200 deductible, has a monthly premium of $296. UnitedHealthcare’s 360-day STLDI plan, with a $7,000 out-of-pocket maximum and a $5,000 deductible, has a monthly premium of $209—a savings of 29% for a plan that has a slightly lower deductible and better out-of-network protection.

However, it is also cheaper for such an individual to upgrade to a more comprehensive STLDI plan. A 30-year-old male nonsmoker in Fulton County who enrolls in the Blue Cross ACA plan pays $467 per month to purchase Silver insurance coverage; the United STLDI plan that offers Silver-like insurance coverage charges a premium of $250 per month—a savings of 46%. For these young, nonsmoking enrollees, the potential savings from switching from ACA to STLDI coverage are therefore greater if they wish to purchase more comprehensive insurance protection.[42]

It is often assumed that ACA plans are more attractive than STLDI for those who are high-risk (such as tobacco smokers or those in older age groups), but this is not necessarily true. According to one website that sells both types of plans, the average age of its STLDI enrollees (36.3) is similar to its ACA enrollees (37.9).[43] Moreover, UnitedHealthcare’s STLDI monthly premium for a 60-year-old male smoker purchasing a Bronze-like plan is $742, which is 5% less than the $779 premium for the Blue Cross Bronze plan (Figure 3). For such an individual, the potential savings to be gained from switching from an ACA to an STLDI plan are again much larger for more generous coverage. The monthly premium for UnitedHealthcare’s Silver-like STLDI plan ($888) with an annual deductible is 28% less than the $1,227 cost of the Blue Cross Silver plan.

For both catastrophic and comprehensive coverage, premiums for the 60-year-old smoker are roughly three times what they are for the 30-year-old nonsmoker—and consistently much lower under STLDI. This is because ACA plans are also allowed to adjust premiums within defined bands according to age and smoking status, and the 3:1 ratio permitted for age-rating was designed to mimic the actuarially fair price disparity.[44]

Accusations that STLDI plans are “skinny plans” or “junk plans” are based on the fact that this form of insurance is exempt from ACA’s “essential health benefit” mandates and, in particular, suggest that they fail to cover mental health, substance abuse, prescription drugs, and maternity services.[45] But while not all STLDI plans include these benefits, many do.

A 2018 Kaiser Family Foundation study examined the share of STLDI plans offering various covered benefits—especially mental health, substance abuse, prescription drugs, and maternity—that were available in the largest (most populous) metropolitan area in every state.[46] A more relevant comparison is to look at the total number of plans in these markets that offer the benefits—taking into consideration (which the KFF analysis did not) whether the availability of various STLDI plans may be associated with state regulations that limit their sale.

Figure 4 offers an overview (the Appendix has a more detailed, state-by-state breakdown). In the 16 states where STLDI plans are fully available under federal rules (terms up to a year before deductibles are reset, plans renewable for up to three years), the median number of plans in the largest metro areas offering mental health coverage is 12, and the median number of plans offering substance abuse and prescription drug coverage is seven. Only in Alaska and Montana do all STLDI plans fail to offer mental health, substance abuse, or prescription drug coverage. Even in states that impose restrictions on STLDI, a variety of comprehensive coverage options are widely available. The only ACA “essential health benefit” unavailable through STLDI is maternity coverage—which relates to a medical condition that is uniquely uninsurable.

The conventional wisdom that STLDI plans fail to offer broad coverage is mistaken. Other supposed shortcomings of STLDI have also been greatly exaggerated. Consider: a preexisting condition is more a reference to whether insurance is purchased before an individual falls sick than it is to inherently uninsurable medical conditions.[47] Even preexisting conditions do not necessarily disqualify one from buying STLDI coverage for other medical risks: only 13% of attempted enrollees were unable to purchase coverage through the STLDI market.[48]

The main reason that the Medical Loss Ratio of STLDI plans has traditionally been lower than that for ACA plans is because the term length was shorter. Even before the three-month restriction was imposed, the average enrollment length in STLDI plans was only 201 days.[49] As individuals are now allowed to buy STLDI for longer time periods, including renewal for several years, the administrative costs associated with initial enrollment will be spread over more medical coverage.[50] Furthermore, while ACA plans must spend 80% of all revenues on medical costs across all enrollees in the aggregate, the expected value of medical benefits from enrollment in a costly, high-deductible ACA plan to an individual of low or average risk may be only 10%–20% of his premiums.

Overall, a recent survey by eHealth found that 91% of STLDI enrollees were either “very satisfied” or “somewhat satisfied” with their plan.[51] This compares well with Gallup’s finding of 84% in these satisfaction categories for those enrolled in employer-sponsored insurance and 70% for individuals receiving coverage (often subsidized) through ACA individual market plans.[52]

The Net Effect of STLDI Deregulation

As noted earlier, the 2016 rule restricting STLDI plans was primarily justified by reference to the concern that they threaten to undermine protections for individuals with preexisting conditions, by driving up ACA plan premiums. To assess the merits of this concern and the net effects of STLDI deregulation, it is necessary to examine separately the potential consequences for distinct subsections of the American population.

The deregulation of STLDI plans makes little immediate difference for the 156 million Americans currently covered by employer-sponsored insurance and the 112 million Americans enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The same is also true of the 6 million Americans enrolled in individual ACA plans whose premiums are subsidized (as a consequence of earning between 100% and 250% of the federal poverty level.)[53] The impact of deregulating STLDI largely concerns those without access to these sources of health-insurance coverage, who fall into three distinct groups:

• The 29 million currently uninsured, who may become able to afford insurance coverage;[54]

• The 9 million, currently enrolled in non-group ACA plans, ineligible for cost-sharing reduction subsidies and without major preexisting conditions, who may be able to save money by switching to STLDI plans;[55]

• The 1 million, currently in unsubsidized ACA plans, with major preexisting conditions, who may see ACA premiums increase.[56]

Various studies have therefore attempted to estimate the magnitude of likely effects for each of these three groups (Figure 5).

There is broad uncertainty about the magnitude of the reduction in the number of uninsured Americans as a result of STLDI deregulation, but all five studies agree that it will be significantly reduced—the estimates range from 200,000 to 3.7 million. The White House’s Council of Economic Advisers estimated that a 700,000 decline in the number of uninsured Americans resulting from STLDI deregulation could save hospitals $1.1 billion in uncompensated care.[57]

Although only two of these studies estimated the likely premium declines for individuals switching from ACA to STLDI plans, they agreed that this was likely to be around 50%—a figure similar to the estimate in Figure 3 of potential savings for a 30-year-old nonsmoker switching to a Silver-like, yearlong STLDI plan in Fulton County, Georgia. All five studies predicted that the likely impact of STLDI deregulation on the premiums paid by unsubsidized individuals remaining in ACA plans was likely to be relatively minor, with estimates ranging from increases of 1% to 9%.

After reviewing rate filings for 2019, KFF found that insurers attributed an average 6% increase in unsubsidized ACA premiums to the combined effect of STLDI deregulation, the deregulation of Association Health Plans, and the repeal of the individual mandate.[58] But the median estimated increase in ACA premiums attributed specifically to STLDI deregulation by insurers seeking to justify ACA rate increases to regulators was less than 1%, and 92 of 124 requested rate increases failed to mention STLDI deregulation as a significant factor at all.[59]

ACA premiums increased by 3% on average for 2019, the year STLDI deregulation went into effect—the only single-digit increase since ACA regulations were implemented in 2014, and a dramatic stabilization from the 30% increase in 2018.[60] On average, ACA premium increases for 2019 were most substantial in states that banned the renewal of STLDI plans (7.3%) or those that prohibited them entirely (+6.7%). ACA premiums declined on average in states that merely restricted STLDI terms to less than a year (-1.7%) or allowed them fully, according to federal rules (-0.2%).[61]

Whether STLDI deregulation leads to an increase in federal spending—as exchange subsidies expand automatically to offset the flight of healthier enrollees from the risk pool—or whether this effect is outweighed by savings generated by the departure of subsidized enrollees to unsubsidized STLDI plans, remains to be seen. Substantial uncertainty similarly remains regarding likely enrollment levels, as well as the degree to which STLDI plans are allowed by state legislatures and regulators to substitute for ACA plans. Several of the estimates in Figure 5 are based on assumptions that likely underestimate the relative appeal of STLDI plans to older individuals, and none attempts to model the impact that guaranteed renewability of STLDI coverage will have in keeping individuals from moving back to the ACA’s risk pool as they get sick. Nonetheless, CBO has assumed that 95% of those shifting from ACA to STLDI coverage will do so in search of comprehensive benefits, rather than so-called skinny plans.[62]

All estimates agree that STLDI deregulation is likely to result in a significant reduction of the number of uninsured and substantial potential reductions in premiums for those currently unsubsidized who switch to short-term plans before they get sick. While many have accused STLDI deregulation of causing premiums to increase for unsubsidized ACA enrollees with preexisting conditions, the estimated magnitude of any such effect is so slim that it is essentially nonexistent.

Conclusion

In 2018, the federal government provided $55 billion in subsidies for plans offered on the ACA exchange.[63] These subsidies bore most of the cost of health-care premiums for 6 million low- and moderate-income Americans and indirectly secured coverage guarantees for 1 million others who had preexisting conditions. But the ACA’s insurance pricing reforms were unnecessary to the ACA’s coverage expansions and served largely to engender dysfunction on the individual market, especially for those who were ineligible for premium subsidies. The ACA’s community-rating rules function as a regulatory tax on insurance, and so the more insurance protection people wish to purchase, the worse value they get from ACA plans. Many stopped purchasing insurance altogether, with the individual mandate penalty making little difference.

The emergence of STLDI plans as an alternative has allowed individuals ineligible for subsidies to buy health insurance at premiums that offered much better value, given their medical risks. STLDI plans allow premium savings of up to 46% and access to a broader range of doctors and hospitals. They can also reduce the cost of more comprehensive insurance coverage for all medical services except maternity. The adverse impact of the availability of STLDI plans on the premiums for unsubsidized individuals who remain on the ACA’s exchange is insignificant.

STLDI has been deregulated on the federal level, and several states have followed through, opening up an alternative to ACA plans that many consumers have found valuable. Some states have restricted these plans, and others have banned this form of insurance. State restrictions or bans are mistaken; and attempts to cripple these plans at the federal level would be worse. Insurance-market regulations serve an essential purpose in protecting consumers from misleading marketing practices, unanticipated gaps in coverage, or insurers that lack the funds needed to reimburse claims as promised. But their role should be to protect consumers and to help them get a good deal—not to trap them in redistributive schemes by eliminating the most attractive coverage options.

Appendix

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).