The Preschool Debate: Translating Research into Policy

Editor's note: The following is the third chapter of The Next Urban Renaissance (2015) published by the Manhattan Institute.

Introduction

There is a broad consensus that the United States should expand its current preschool programs, particularly for disadvantaged students. This consensus reflects both a general interest in improving the preparation of students entering schools and a particular concern that disadvantaged students are especially handicapped by current preschool educational experiences. Matched with this desire to improve school preparation is evidence that at least some preschools are able to significantly improve the outcomes of their students.

The calls for expanded preschool programs—frequently coming to rest on ideas of universal preschool for all four-year-olds—became national news when introduced in New York City and New York State. These policy moves echoed proposals from President Obama and a wide range of state policy leaders in other states. Most recently, the president introduced the idea of offering incentives to states to develop new and improved programs.

Arguments for new and expanded preschool almost invariably make large leaps in generalizing from existing evidence of preschool effectiveness. The clearest evidence of the latter comes from evaluations of two high-quality programs conducted decades ago. Nonetheless, these small-scale, very expensive efforts bear little relationship to any of the programs espoused in current policy discussions.

Indeed, much of the present discussion skirts mention of evidence from the most significant preschool program currently in existence: Head Start. For a half-century, the federal government has run this national preschool program, currently serving more than 900,000 disadvantaged students at an annual cost of over $8.5 billion. Yet every periodic evaluation of this program casts considerable doubt on its efficacy in improving student performance (let alone its efficiency in spending taxpayer money).

When considering a mass expansion of public pre-K, two central questions arise. First, what should be the characteristics of new, broader preschool programs? Second, how best should such programs be taken to scale? Unfortunately, available evidence provides limited guidance on both issues. Because we lack basic information about program design and program implementation, it would be foolhardy to move directly into a broad universal pre-K program. We should act on preschool, but in a way that generates information on how to develop and improve programs.

Preschool programs are particularly well suited for high-quality evaluations. The key is to develop a systematic program for expanded preschool such that the outcomes are readily observed and direct experimentation emphasized. Three design elements should receive high priority: evaluate incentives for outcomes; vary resources and inputs; and mix public and private provision.

I. The Case for Expanding Pre-K

Considerable attention has rightfully focused on early-childhood education programs, particularly for children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. At the same time, much of the public discussion treats preschool programs as a knife-edge issue: society either has them or does not have them. Unfortunately, this treatment does not lead to enlightened public policy.

This essay provides perspective on the existing knowledge base and the range of decisions required to develop a comprehensive, effective pre-K policy. The essay touches on ongoing politics, programmatic choices, and policy decisions in New York City and New York State. The latter are also embedded in a national conversation, led by President Obama, potentially carrying through to significant new federal funds to encourage broader state initiatives.1

This author’s intent is not to critique these statements and proposals but instead to provide a way for all parties to better understand where current and projected policies fit into the overall pre-K picture.2 There are two straightforward ways to marshal attention to quality preschool programs. On the demand side, we know that there are significant variations in the preparation of children for schooling and that these variations are systematically related to families’ socioeconomic status. On the supply side, we have credible evidence that quality preschool can significantly improve achievement and life outcomes of disadvantaged students.

Deficits at Entry into School

Existing evidence suggests that a direct line can be drawn tracing the impact of skills acquired in childhood across an individual’s life. This linkage of early experiences and performance to adult and societal outcomes underscores the former’s importance. Such experiences and performance are closely tied to family background, implying an intergenerational linkage with large societal implications. Therefore, consideration of early skills relates directly to topics of income distribution and intergenerational mobility.

Evidence from a wide variety of sources indicates that disadvantaged students have less education in the home before entry into school. The Coleman Report, the massive governmental report mandated by the 1964 Civil Rights Act, first documented early achievement differences by family background.3 These differences, documented in 1965, focused on racial differences.

When tests were given at grades one, three, six, nine, and 12, two facts stood out. First, black students in the first grade fell 0.75 to one standard deviation below white first-graders in the same region. In terms of the distribution of white students’ scores, such differences imply that the average black first-grader started at between the 16th and 23rd percentiles of the white distribution. Second, the gaps seen in 1965 grew across grade levels.

Another important investigation, by Betty Hart and Todd Risley, looked at the vocabulary of children and found dramatic differences by parents’ socioeconomic status.4 Both the amount and quality of parent-child interactions differed significantly, leading to large differences in vocabularies that directly reflected parental background.

More recently, data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study documents the continuing early achievement deficits that accompany family background. Fryer and Levitt identify gaps in scores by socioeconomic status,5 while Reardon suggests that these gaps may have widened over many years.6

How important are these initial gaps? Considerably so: while there is some disagreement about whether they shrink, expand, or hold constant over time, there is no evidence that they actually disappear.

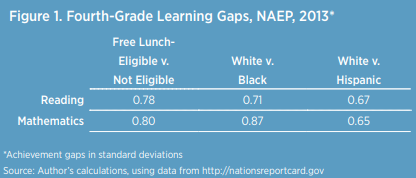

National testing of students under the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)—often called the “nation’s report card”— begins at grade four. Figure 1 reveals that, in 2013, fourth-grade reading gaps were enormous. Blacks trail whites by 0.71 standard deviations; Hispanics trail whites by 0.67 standard deviations; and those eligible for free, or reduced-price, lunch trail higher-income students (who are not eligible) by 0.78 standard deviations. Fourth-grade math gaps are similarly large. Such gaps indicate challenges of monumental proportions: a person who is 0.8 standard deviations below the more advantaged average falls at the 21st percentile of distribution.

The final demand-side element for preschool is the significant impact on individuals’ future incomes. The most direct relationship between early test performance and earnings is found in the work of Chetty, which traces kindergarten performance directly to college com- pletion and early career earnings.7 Other evidence of the skills-earnings relationship comes from recent surveys of adults and their labor-market experiences. The OECD conducted the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) in 2011–12.8 From these data, it is possible to estimate the returns to greater cognitive skills. Importantly, the returns are higher in the U.S. than in any of the other 22 countries surveyed by the OECD (i.e., the U.S. economy rewards skills more than other developed countries do).9

Such returns are high in absolute terms, too. For instance, scoring at the 84th percentile of the numeracy skills distribution, rather than at the mean of distribution, implies 28 percent higher wages throughout a person’s working life.10 Scoring at the 16th percentile implies 28 percent lower earnings throughout a person’s life. While recent public and me- dia focus has largely concentrated on the top 1 percent of earners, such results thus point to the enormous implications of skill gaps within the remaining 99 percent of earners.11

Ameliorating Early Deficits

Nobel-winning economist James Heckman has contributed greatly to the body of literature in support of the importance of early-childhood education.12 Substantial evidence from numerous studies confirms an intuitive proposition: skills beget skills. In particular, early skills make acquisition of subsequent skills easier.13 This dependency of skill development on prior skills highlights the particular disadvantage of starting school at a low skill level.

But just how effective are preschool programs in boosting the school readiness of disadvantaged youth? Certain studies with strong research designs, based on random assignment of students to programs, suggest high efficacy: the Perry Preschool Project is perhaps the best known, but others, such as the Carolina Abecedarian Project and the Early Training Project, also provide important evidence in favor of early-childhood education.14

Cost-benefit analyses of Perry Preschool suggest that the program was effective, conferring social benefits significantly in excess of expenditures.15 In one widely cited evaluation, benefits exceeded costs by a factor of six.16 Returns of this kind, if widely reproducible, clearly justify intensive preschool investment—and, where the market fails to elicit appropriate private responses, substantial public investment. Yet most other cost-benefit evidence on preschool outcomes is less certain and indicates smaller positive effects. In other locations, experimental evidence has been supplemented by observational studies.

Chicago’s Child-Parent Center program, still operating in the city’s public schools, is a highly cited example of the latter.17 Child-Parent Center is lower-cost than Perry or Abecedarian; its benefits are also considerably less certain. More recently, studies on preschool outcomes in Tulsa, Oklahoma—meant to assess the state’s universal pre-K program—provide another interesting, albeit limited, evaluation of mass pre-K expansion.18 Still more recently, this evaluation was expanded to include Georgia’s universal pre-K program.19 Available evidence for both states indicates a positive impact for disadvantaged children and no impact for non-disadvantaged kids.20

On the negative side of the pre-K results ledger lies, notably, the federal Head Start program—now administered for a half-century, at great expense, and extensively evaluated.21 One recent high-quality evaluation found that any achievement gains produced by Head Start disappear by third grade.22 Many more pre-K programs have not been evaluated and thus provide no information on efficacy.

Summary

- Early acquisition of skills is important for fully developing individ- uals’ potential.

- Large differences in early skills directly relate to family background.

- Skills offer a significant labor-market payoff.

- Some quality preschool programs display positive returns.

- The exact magnitude of impact varies widely, presumably with program characteristics.

- Such findings offer justification for public action.

II. Translating Evidence into Policy

Such findings do not, alas, translate easily into sound public policy. Developing an actual set of policies requires filling in the details. To set the scene for the issues that must be addressed, it is useful to dig one layer below the evidence just presented. To be clear, the purpose of this exercise is not to deny the strong case for improving the country’s preschool programs but rather to move the discussion to a level more appropriate for policy deliberation.

The first detail of note is the importance of knowing the target student population. In 2011, two-thirds of all U.S. four-year-olds were enrolled in preschool programs—though this figure is lower for the children of less educated parents, single-parent families, and nonwhite families.23

“We should act on preschool, but in a way that generates information on how to develop and improve programs. It would be foolhardy to move directly into a broad universal pre-K program.”

The second detail of note is the cost of existing preschool programs. The experimental programs discussed (which provide the clearest evidence of positive impact) are not typical. Perry Preschool, estimated to cost more than $15,000 per child (in 2000 dollars), involved intensive treatment by teachers with master’s degrees in child development, student-teacher ratios of 6:1, and regular home vis- its (though the program ran only from October through May).24 Carolina Abecedarian—a full-day, five-days-per-week, 50-weeks-per-year, five-year program beginning at birth and in- cluding medical care and home visits25—was estimated to cost $75,000 per child (2002 dollars).

Such experiments are plainly not financially realistic for broad imitation in most states. Such experiments were also very small and provided no information on their most essential components or what more modest versions might resemble.26 Head Start is considerably different from Perry Preschool and Carolina Abecedarian. In 2005, only 35 percent of Head Start teachers held a bachelor’s degree, with Head Start programs varying considerably in length and intensity. In addition, if run on a full-time, full-year basis, per-child costs are estimated to exceed $20,000 annually.27 The third detail of note is that virtually all the aforementioned pre-K programs’ benefits accrued to girls; boys were, at best, likely to reap no benefit.28 Further, a substantial part of such benefits fell outside academics: Perry Preschool’s most significant benefit (around 70 percent) related to reduced criminal behavior.29

III. Questions for Developing Policy

To develop effective, efficient preschool programs, the following questions must be considered.

What Is Quality Pre-K?

Almost all discussions of preschool expansion specify that the goal is to create “high-quality preschool.” These discussions generally focus on various inputs to the desired program—defined, say, in terms of pro- viders’ qualifications, adult-to-child ratios, and attributes of the physical teaching space. Yet there is no reliable evidence on how these attributes relate to desired outcomes. At the same time, each input requirement has resource implications, with total program expenses and efficiency of provision directly affected by input choices.

How Should Pre-K Be Provided?

The current structure of U.S. pre-K programs involves mixed pub- lic and private provision. More than one-third of four-year-olds are now enrolled in private preschool (for families above the poverty line, this figure is higher).30 Views also differ widely on how best to provide for any pre-K expansion. Some desire purely public provision—transition- ing from the current public K–12 to a public “P–12” system—largely to ensure minimum standards of quality. On the other end of the spec- trum, some desire a pure voucher program, with goals such as parental choice, competition among suppliers, and more efficient provision.31

Should Pre-K Be Mandatory?

If programs are optional, children most in need may be less likely to enroll. Indeed, some of the nonattendance at existing preschool programs derives not from lack of resources or availability but from lack of parental interest. Still, mandatory pre-K may not garner sufficient public support.

What Role for Incentives?

Much discussion has focused on top-down mandates: quality standards, regulations for participation, and so on. Instead, using incentives— to encourage families to enroll and to encourage providers to produce quality programs for a given cost—offers considerable advantages. Indeed, if one can assess program outcomes, one can design rewards and punishments for programs based on desired outcomes (with no need to speculate on the implications of different inputs).

How Should Pre-K Expansion Be Financed?

Preschool enrollment is, as mentioned, already privately financed to a significant degree, especially among higher-income families. As such, if preschool were made free (i.e., taxpayer-financed) to all families, it would amount to a large public subsidy to the middle class and the affluent, who would likely substitute public funding for (their current) private funding. The inequity of such a development would be at odds with most arguments for expanding preschool.32 Instead, means testing—with families making sliding payments based on income—would avoid such an outcome. Yet here, too, a difficulty emerges: insufficient information on program enrollment sensitivity to prices and subsidies.33

What to Do About Head Start?

Even as President Obama calls for expanding preschool, Head Start stands out as a major program (2014 price tag: more than $8.5 bil- lion) that displays little in terms of desired outcomes for its 900,000 enrollees. (In 2006, 26 percent of American children in poverty attended Head Start programs.)34 It would thus appear that an expensive public program continues at the detriment of its (mostly disadvantaged) par- ticipants. Can Head Start be steered in a more productive direction? Or do its shortcomings suggest the great difficulty of “going to scale” with public programs?35 Considerable political support exists for its continuation, if not expansion; but Head Start, as constituted, is inconsistent with efforts to promote access to high-quality preschool.

IV. The Path Forward

The preceding discussion presents a real dilemma. There is strong evidence in favor of improving and expanding existing preschool services, particularly for disadvantaged children. There are also fundamental design questions—and little existing information to usefully answer them.

To the latter, some expansion advocates retort that the goal of politics is to find a societal solution to difficult questions: “Just do it,” they urge.36 But with considerable competition for public funds, a more rational approach (though one, admittedly, that does not re- quire all pre-K expansion to be halted until all questions have been answered) seems justified.

Such an approach would involve developing a program of experimentation designed to add information, over time, to the open questions discussed. Currently, it is common to introduce broad, uniform programs to the entire eligible population. Unfortunately, such programs are unlikely to provide much, if any, usable information that can provide evidence for developing programmatic detail or alterations. On the other hand, considerable information can be gained from planned programmatic variations introduced alongside a comparison group.

Preschool expansion lends itself well to such experimentation. Three areas should receive high priority in establishing evidence on outcomes:

1. Evaluate incentives for outcomes. As a rule, all preschool programs should be judged on the basis of observed student outcomes (especially vital when expanding programs). Yet most programs are not systematically assessed, with few incentives for better outcomes.37 Instead, experiment by offering different preschool centers different outcome incentives, and then evaluate the results.

2. Vary resources and inputs. Much discussion focuses on defining preschool quality. Yet little evidence directly relates different input combinations to child outcomes. Instead, vary overall funding and input requirements to assess student impact.

3. Mix public and private provision. Current preschool provision involves a mix of public and private. Here, too, little information exists on which to base overall decisions on the optimal structure of provision. Instead, introduce funding in a way that provides information on how public versus private provision compares in efficacy and efficiency.

Conclusion

Translating research on the general importance of expanded preschool into effective governmental programs requires information that simply does not exist. While we should proceed with preschool expansion—because this offers clear gains, given current programmatic shortcomings—we should do so in a thoughtful way that develops a continuous improvement program and uses the early experiences of expanded programs to inform later developments. If, however, we simply plunge into an immediate move toward universal preschool, we will probably make it impossible to learn from pre-K expansion. This is likely to produce very expensive programs that are less effective than desired.

Some discussions of preschool overpromise on results, naively suggesting that most of the current problems with U.S. K–12 schooling would be solved merely by better preschool programs. Alas, there is no evidence suggesting this to be true. There would be benefits from getting disadvantaged students better prepared for school; but without widely effective public schools, such benefits are inherently limited. Indeed, one of the common explanations for the “fade-out” of Head Start—the tendency for gains at kindergarten to disappear after a few years of schooling—is that the schools that receive Head Start completers are not of sufficiently high quality.

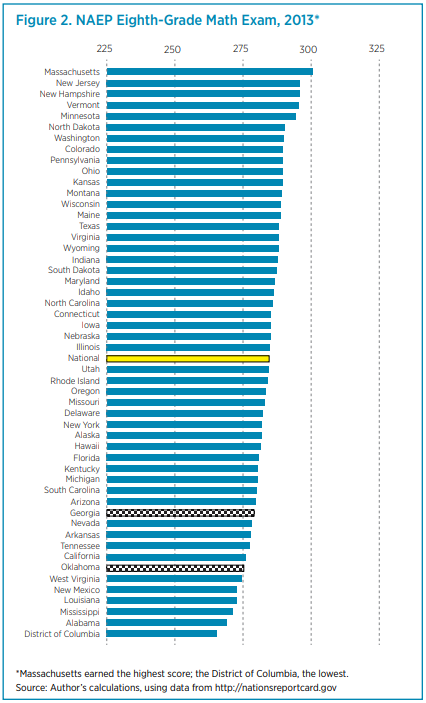

Consider the experiences of Georgia and Oklahoma, which introduced universal preschool in the 1990s. If the latter were indeed a silver bullet, one would expect both states to rank highly in student achievement. Yet their poor respective performances on the 2013 NAEP eighth-grade math exam (Figure 2) indicates that universal preschool is hardly a panacea. There is no substitute for high-quality K–12 schooling. Nor is it likely that simply spending more on schools will cure America’s current K–12 ills.38 To that end, ensuring that high-quality teachers are present at all grade levels is critical.39 To achieve this, reforming educational incentives—through stronger accountability, greater parental choice of schools, and better rewards for effective

schools and teachers—is equally vital.

In the quest to improve education outcomes for all Americans, high-quality preschools will help but must be linked with high-quality K–12 schools. This is not only a moral goal but also one rooted squarely in the national interest.40

Endnotes

1. A call for universal preschool was included in President Obama’s 2013 State of the Union Address; see Office of the Press Secretary, the White House, “Fact Sheet: Pres- ident Obama’s Plan for Early Education for All Americans (Washington, D.C.: 2013). Added funding for this was subsequently announced by President Obama in December 2014; see Justin Sink, “Obama to Unveil $1B Early Childhood Education Funding,” The Hill (December 10, 2014).

2. The current, wide-ranging discussion is visible in books focused on policy issues, in- cluding Chester E. Finn, Jr., Reroute the Preschool Juggernaut (Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution, 2009); Bruce Fuller, Standardized Childhood: The Political and Cultural Struggle over Early Education (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2007); David

L. Kirp, The Sandbox Investment: The Preschool Movement and Kids-First Politics (Cam- bridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2007); and Edward Zigler, Walter S. Gilliam, and Stephanie M. Jones, A Vision for Universal Preschool Education (New York: Cam- bridge University Press, 2006). This essay does not attempt to review all arguments but instead highlights issues most salient to current discussions.

3. James S. Coleman et al., Equality of Educational Opportunity (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1966).

4. Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children (Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes, 1995).

5. Roland G. Fryer, Jr., and Steven D. Levitt, “Understanding the Black-White Test Score Gap in the First Two Years of School,” Review of Economics and Statistics 86, no. 2 (May 2004): 447–64.

6. Sean F. Reardon, “The Widening Academic Achievement Gap Between the Rich and the Poor: New Evidence and Possible Explanations,” Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality and the Uncertain Life Chances of Low-Income Children, ed. Richard J. Mur- nane and Greg J. Duncan (New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press, 2011).

7. Raj Chetty et al., “How Does Your Kindergarten Classroom Affect Your Earnings? Evidence from Project STAR,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 126, no. 4 (November 2011): 1593–1660.

8. See OECD Skills Outlook 2013: First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills (Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2013). PIAAC’s target population was the noninstitutionalized population, aged 16–65. PIAAC tested various cognitive domains of 5,000 or more adults in 24, mostly OECD, countries. PIAAC assessments—designed to provide international comparisons of adult skill levels— measure three cognitive skill areas needed to advance in the workplace and society: numeracy, literacy, and problem solving in technology-rich environments.

9. Eric A. Hanushek et al., “Returns to Skills Around the World,” European Economic Review (2013).

10. These estimates derive from statistical analysis relating the log of weekly earnings to measured numeracy skill, experience, experience squared, and gender. Math skills are normalized to mean zero and standard deviation one. The comparison with the 84th percentile represents being one standard deviation above the mean in numeracy perfor- mance; the 16th percentile represents being one standard deviation below the mean in numeracy performance. Similar estimates derive from substituting literacy assessments for numeracy (though the returns to problem-solving skills are less significant).

11. See also David H. Autor, “Skills, Education, and the Rise of Earnings Inequality Among the ‘Other 99 Percent,’ ” Science 344, no. 843 (May 23, 2014): 843–51.

12. See, e.g., Pedro Carneiro and James J. Heckman, “Human Capital Policy,” in Inequality in America: What Role for Human Capital Policies?, ed. Benjamin M. Friedman (Cam- bridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2003), 77–239; Flavio Cunha and James J. Heckman, “The Technology of Skill Formation,” American Economic Review 97, no. 2 (2007): 31–47; and Flavio Cunha and James J. Heckman, “Formulating, Identifying and Estimating

the Technology of Cognitive and Noncognitive Skill Formation,” Journal of Human Resources 43, no. 4 (fall 2008): 738–82.

13. Commonly labeled “dynamic complementarity”; see Flavio Cunha et al., “Interpreting the Evidence on Life Cycle Skill Formation,” in Handbook of the Economics of Educa- tion, ed. Eric A. Hanushek and Finis Welch (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006), 697–812.

14. Lawrence J. Schweinhart et al., Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40 (Ypsilanti, Mich.: High/Scope Press, 2005); and John F. Witte, “A Pro- posal for State, Income-Targeted, Preschool Vouchers,” Peabody Journal of Education 82, no. 4 (2007): 617–44. A comprehensive review of different pre-K programs and their evaluations can be found in Douglas J. Besharov et al., “Summaries of Twenty-Six Early Childhood Evaluations,” Welfare Reform Academy (College Park, Md.: University of Maryland, 2011).

15. Edward M. Gramlich, “Evaluation of Education Projects: The Case of the Perry Pre- school Program,” Economics of Education Review 5, no. 1 (1986): 17–24; W. Steven Barnett, “Benefits of Compensatory Preschool Education,” Journal of Human Resourc- es 27, no. 2 (spring 1992): 279–312; Ellen Galinsky, Economic Benefits of High-Quality Early Childhood Programs: What Makes the Difference? (New York: Committee for Economic Development, 2006); and Clive R. Belfield et al., “The High/Scope Perry Preschool Program,” Journal of Human Resources 41, no. 1 (winter 2006): 162–90.

16. Belfield et al., “The High/Scope Perry Preschool Program.”

17. Arthur J. Reynolds et al., “Age 21 Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Title I Chicago

Child-Parent Centers,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 24, no. 4 (2002): 267–303. The evaluation of the program relies on matching participants with compa- rable students in similar schools. The validity of this approach rests on the uncertain assumption that similar students, as measured by only a few characteristics, provide a sufficiently good control group.

18. William T. Gormley, Jr., et al., “The Effects of Universal Pre-K on Cognitive Develop- ment,” Developmental Psychology 41, no. 6 (2005): 872–84.

19. Elizabeth U. Cascio and Diane W. Schanzenbach, “The Impacts of Expanding Access to High-Quality Preschool Education,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (fall 2013): 127–78.

20. Ibid.

21. In practice, Head Start is not a unified program but rather a funding stream with loose regulations on the character of actual programs. As such, Head Start programs display considerable heterogeneity.

22. The first random-assignment evaluation of Head Start assessed a variety of child outcomes, with none showing significant impact by third grade: Michael Puma et al., Third-Grade Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study Final Report (Washington, D.C.: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families,

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012).

23. U.S. Department of Education, Digest of Education Statistics, 2012 (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, 2013), table 57. Preschool enrollment falls below 40 percent for three-year-olds.

24. Cost estimates and programmatic comparisons are found in Witte, “A Proposal for State, Income-Targeted, Preschool Vouchers.” Children participated for one or two years: the

$15,000 figure represents the average cost for all participants. (For a new program, costs per child would presumably be larger if all students participated for two years.)

25. Frances A. Campbell and Craig T. Ramey, “Cognitive and School Outcomes for High- Risk African-American Students at Middle Adolescence: Positive Effects of Early Inter- vention,” American Educational Research Journal 32, no. 4 (winter 1995): 743–72.

26. The Perry Preschool treatment group consisted of only 58 children; Carolina Abecedari- an, 57; and the Early Training Project, 44. Campbell and Ramey, “Cognitive and School Outcomes for High-Risk African-American Students at Middle Adolescence”; and Frances A. Campbell et al., “The Development of Cognitive and Academic Abilities: Growth Curves from an Early Childhood Educational Experiment,” Developmental Psychology 37, no. 2 (2001): 231–42. Small sample sizes obviously raise concern about whether evaluation results can be generalized to far larger programs.

27. The cost of Head Start is usually reported as slightly over $7,000 per pupil, per year (2003–04 dollars), derived by dividing total program costs by total participants. Yet as welfare specialist Douglas Besharov notes, such calculations mix a variety of different programs; see Besharov et al., “Summaries of Twenty-Six Early Childhood Evaluations.”

28. Michael L. Anderson, “Multiple Inference and Gender Differences in the Effects of Early Intervention: A Reevalution of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and Early Train- ing Projects,” Journal of the American Statistical Association 103, no. 484 (December 2008): 1481–95.

29. Belfield et al., “The High/Scope Perry Preschool Program.”

30. U.S. Department of Education, Digest of Education Statistics, 2012, table 56.

31. The efficiency of current, publicly provided K–12 schooling does not lead to optimism about potential outcomes in a (hypothetical) mass expansion of public pre-K; see Eric

A. Hanushek, “The Failure of Input-Based Schooling Policies,” Economic Journal 113, no. 485 (February 2003): F64–F98.

32. Cascio and Schanzenbach, in “The Impacts of Expanding Access to High-Quality Pre- school Education,” observe a considerable shift to subsidized public programs after the adoption of universal preschool in Georgia and Oklahoma.

33. Dueling visions can be seen in current policy analyses in Kirp, The Sandbox Investment; and Fuller, Standardized Childhood.

34. U.S. Department of Education, Digest of Education Statistics, 2012, table 60.

35. There is little evidence that any educational policy extracted from the scientific evalua- tion literature has been successfully implemented across the heterogeneous districts of states. Available science, in other words, does not support regulatory and implementa- tion policies that reliably replicate evaluation results broadly.

36. One extension of the “just do it” argument notes that programs designed exclusively for the poor tend to be of low quality. Broad programs involving the middle class, the argument runs, yield stronger political support that pushes them toward higher quality.

37. Numerous questions have been raised over the ability to reliably measure preschool outcomes. Nevertheless, there is an expanding set of performance measures that can assess outcomes. It is also possible to trace preschool impact into K–12 schools.

38. Eric A. Hanushek and Alfred A. Lindseth, Schoolhouses, Courthouses, and Statehouses: Solving the Funding-Achievement Puzzle in America’s Public Schools (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009).

39. Eric A. Hanushek, “The Economic Value of Higher Teacher Quality,” Economics of Education Review 30, no. 3 (June 2011): 466–79; and idem, “Valuing Teachers: How Much Is a Good Teacher Worth?,” Education Next 11, no. 3 (summer 2011).

40. As documented in Eric A. Hanushek, Paul E. Peterson, and Ludger Woessmann, Endan- gering Prosperity: A Global View of the American School (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2013), U.S. students, high- and low-performing alike, are generally not competitive with students in many other developed countries. Addressing both the international competiveness and domestic achievement gaps would have enormous positive implications for America’s future prosperity.