Post-Employment Benefits in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut: The Case for Reform

Governments at all levels offer their retired employees a wide range of benefits apart from pensions. These other post-employment benefits, or OPEB, typically include medical insurance. Depending on the type of benefits offered, how they are financed, and whether they cease when the retiree becomes eligible for Medicare, a government can accrue millions of dollars of unfunded OPEB liabilities a year or none at all.

Because OPEB liabilities are usually lower than pension liabilities, they are considered less of a concern. They are, however, politically difficult to reform, and, more importantly, they are often far more difficult to estimate than a pension liability. This makes OPEB liabilities a riskier type of obligation.

Actuaries attempt to quantify the future cost of OPEB plans by applying assumptions that, hopefully, account for future conditions. However, as liabilities increase in complexity, the ability to produce accurate assumptions declines. Moreover, the difficulty associated with predicting complex liabilities increases with time. For example, a life-insurance plan is primarily concerned with mortality rates, investment rate of return, and payroll growth. A health-insurance plan must consider mortality, health-care cost increases, inflation, demographics, health-care regulations, payroll growth, and, in cases where the employer is prefunding, the investment rate of return.

This report explores the complexities of OPEB, particularly in New York State, New York City, Connecticut, and New Jersey. It also considers measures that governments can take to limit their OPEB risks—ranging from providing inflation-indexed, health-care premium subsidies to switching to a subsidy-free OPEB plan. These kinds of reforms are like switching from a defined-benefit pension plan to a cash-balance plan. They mitigate risk to the employer while protecting the employer’s ability to offer employee benefits without, in the case of the public sector, threatening core public services.

OPEB: A Short Course

Governments provide services including public safety, education, health care, and transportation, with the aim of protecting individual rights and providing a social safety net. At lower levels of government, such as municipalities, these services tend to be tailored to better meet the needs and challenges of specific communities. This tailoring makes municipal liability crises—usually created by a combination of bond, pension, OPEB, and deferred infrastructure maintenance liabilities—particularly problematic, as they tend to threaten the most vital services for the least well-off.

While states have struggled with their long-term financial obligations, very few have defaulted on general obligation bonds—the most secure form of debt for investors.[1] On the other hand, municipal bankruptcies are slightly less rare; 69 municipal bankruptcies were filed between 2010 and 2019, nine of them by cities or counties.[2] Even major cities, including New York, Hartford, Detroit, and nearly San Diego, have filed for bankruptcy or had their state governments intervene in recent decades.[3]

The impact of fiscal crises at the municipal level is often devastating and long-lasting, as the damage to a municipality’s credit rating hamstrings its ability to borrow at low rates. Harvey, Illinois, is illustrative. In 2017, an appellate court decided that the city must fund its pension system (2014 population: 25,412),[4] contributing to higher property-tax rates to meet its constitutional obligation to fund the pension plan.[5] The annual required contributions to fund Harvey’s fringe benefits, even with the tax increases, began to crowd out core government services.[6] In 2018, the city laid off 40 public-safety employees—about 25% of its police officers, 40% of its firefighters, and 55% of the non-sworn police personnel.[7]

While the financial dangers posed by underfunded pensions have received a great deal of attention in recent years, the financial dangers posed by OPEB are less well defined. These benefits can include medical, prescription drug, dental, life, disability, and other insurance coverages. OPEB plans can vary significantly from one another because types of coverage, vesting requirements, retirement ages, cost-sharing between the employer and retirees, and benefit rates all vary between governments, employment tiers,[8] and positions.

OPEB benefits can be explicit subsidies, implicit subsidies, and/or access to a state-sponsored plan. Most plans focus on explicit subsidies in the form of the employer paying retirees’ health-insurance premiums and reimbursing prescription drug costs. This form of subsidy is also the most easily accounted for when estimating a plan’s liability.

Implicit subsidies occur when current employees and retirees share a health-insurance plan and the relatively higher health-care utilization by retirees is not financed by higher premiums for retirees.[9] Relative to an explicit or implicit subsidy, a retiree’s access to a state-sponsored plan can appear to be a minor benefit. However, most retirees are better off sharing an insurance pool with active state employees. The ACA exchanges and employer-sponsored plans are distinct markets with different trend rates and, more important for retirement planning, different volatilities, with the ACA individual plan exchange being more volatile.[10] Retirees often live on fixed incomes, and unpredictable changes in annual health-insurance rates can disrupt their expected standard of living.

New York State

The New York State Health Insurance Program (NYSHIP) offers both an Empire Plan and a selection of approved HMO plans to retired state employees.[11] Employees are eligible for different benefits at different times of their life and under different conditions. For example, service-eligible retirees under age 55 can join the state plans but must pay both the employee and employer portion of the premium. The OPEB liability associated with these retirees is effectively zero until they reach age 55, at which point they are eligible for an employer subsidy. However, if an employee is disabled through a work-related accident, he may be entitled to an employer subsidy before age 55. Furthermore, the vesting requirements—which can range from five to 20 years, depending on the agency, position, and when the employee was hired—may be waived for a work-related disability. After covered retirees reach Medicare eligibility, age 65, they are required to enroll in Medicare parts A and B and can receive reimbursements from the state plan in which they are enrolled.

The Empire Plan and approved HMO plans provide retirees (under age 65) with coverage for medical, surgical, hospital, mental health, substance abuse, and prescription drug coverage. In addition to the Empire Plan and HMOs, NYSHIP provides supplementary insurance for retirees enrolled in Medicare, such as the NYSHIP Medicare Advantage HMO and the Empire Plan Medicare Rx. Because most of its non-pension benefits arise from health insurance for retirees aged 55–65, the state’s total OPEB liability can be roughly estimated using NYSHIP’s OPEB liability, reported in the state’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) each year (Figure 1).[12]

The OPEB disclosures within the state CAFRs over the past five years consist of figures that match the fiscal year of the CAFR and of the most recent actuarial valuation, a separate biannual report. Actuarial figures correspond with the actuarial valuation date, while other figures align with the CAFR year. Between actuarial valuations conducted in 2012 and 2016, the state’s OPEB liability grew by 34%, from $54.3 to $72.8 billion. As the plan is operated on a pay-as-you-go basis, no actuarial assets are held against the liability, meaning that the funding ratio is 0%. Instead, employer/employee contributions are deposited into a short-term investment account and dispersed as necessary.

More concerning, between 2014 and 2018 the estimated actuarially required contributions (ARC) grew from $2.3 to $4.3 billion. ARC is the estimated amount necessary to amortize an unfunded pension or other post-employment liability over a period of not more than 30 years. Sharp increases in ARC usually signal higher future operating costs for pay-as-you-go plans. For New York State, the increase in normal costs (that part of ARC representing the future liability for benefits earned in a particular year, as opposed to the unfunded liabilities carried over from previous years) rose only from $1.2 to $1.6 billion a year.

However, the changes in the state’s OPEB liability are partly attributable to changes in the actuarial assumptions over time. For example, the 2018 New York State CAFR notes several major changes to the state’s biannual actuarial valuations. The most recent valuation, 2016, has updated medical costs, discount rates, and tax liability assumptions. These changes have different impacts on the present value of the liability. For example, by reducing the discount rate to reflect lower returns on the state’s short-term investments, the state’s OPEB liability estimate increased.

Connecticut

The Nutmeg State provides two major OPEB plans: the State Employees OPEB Plan (SEOPEBP) and the Retired Teachers Health Plan (RTHP). (There are several smaller plans, such as the Judges, Family Support Magistrates, and Compensations Commissioners Retirement System.) Like New York, Connecticut has different conditions for OPEB eligibility and different benefits at different ages, referred to as “types of retirement.” Connecticut has normal retirement, age 70 retirement, hazardous duty retirement, disability retirement, and vested rights retirement. For SEOPEBP tier IV, normal retirement is defined as starting at ages 63–70, and early retirement is defined as starting at age 58 for nonhazardous duty.[13] Earlier tiers provided earlier retirement options, allowing for normal retirement as early as 55. For teachers (RTHP), normal retirement is age 60, and early retirement is defined as having served 20–25 years. The specific vesting, eligibility, and benefit formula for a given state employee depends on his position and tier.[14]

Connecticut offers four health-insurance plans for non-Medicare, OPEB-eligible employees: Anthem State BlueCare POE Plus; UnitedHealthcare Oxford HMO; Anthem State BlueCare; and UnitedHealthcare Oxford HMO Select.[15] Retirees are required to enroll in Medicare at 65 and are offered coverage in a state-negotiated Medicare Advantage PPO plan from UnitedHealthcare that includes coverage for prescription drugs. The state also provides life insurance equal to 50% or less of the basic coverage amount as of the employee’s retirement, and 100% for employees disabled before age 60. Lastly, the state provides three Cigna dental plans with varying degrees of coverage.

Between normal retirement and age 65, Connecticut usually pays 100% of the retiree’s health-insurance premium, the exception being group 5 employees (retiring October 2, 2017, or later) with fewer than 25 years of services or nonhazardous duty.[16] For early retirees, a “penalty” provision reduces premium subsidies based on how early they begin their retirement and how many years of service they contributed.

Between 2013 and 2017, the state’s total OPEB liability declined, thanks to reforms implemented through a 2017 agreement with a State Employees Bargaining Agent Coalition (SEBAC). As a result of the agreement, Connecticut changed the OPEB plan for retirees over age 65 to Medicare Advantage. The Medicare Advantage reform was largely administrative, changing the way that the federal government reimburses Medicare-covered services and thus reducing the cost of the plan. The total estimated liability declined from $19.7 billion to $17.9 billion (Figure 2), and 95% of the decline is attributable to the Medicare Advantage reform.[17]

The decline is especially impressive, given that the discount rate was also reduced by almost 2%, a prudent move that increases the liability estimate. Over the same period, Connecticut increased its OPEB fund from $143.8 million to $542.3 million, increasing the funding ratio from less than 1% to about 3%. The 2017 SEBAC agreement was largely spurred on by a string of budget crises that continue to plague Connecticut to this day.[18] Between the decrease in ARC and the increase in actual contributions, the percentage of the required contribution that was paid increased from 38% to 65%.

Between the 2015 and 2017 actuarial valuations, Connecticut’s OPEB plan improved by most metrics. However, health-care cost projections return to likely greater-than-economic-growth rates in the early 2020s.[19] This suggests that the 2017 reforms have not made the state’s OPEB plans more sustainable but rather improved their affordability in the short run. Connecticut’s improvement is only impressive relative to itself, as it is one of a handful of states with significant OPEB liabilities.[20] Future reforms, and potential disruptions for state employees and retirees, will likely be required.

New Jersey

The Garden State offers OPEB benefits to state employees, teachers, state colleges, authorities (autonomous state agencies), and municipal governments.[21] While the state administers the municipal government plans, the liabilities of the plans are theoretically those of the cities themselves. Thus, state and municipal OPEB liabilities are separately estimated and presented in the actuarial valuations and the annual state CAFRs.[22] Normal retirement age varies from plan to plan and tier to tier. For example, normal retirement for teachers is ages 60–65, depending on their tier, while state police are eligible at any age after 20 years of service.[23]

New Jersey’s State Health Benefits Program (SHBP) and School Employees’ Health Benefits Program (SEHBP) offer medical, prescription drug, and dental health-insurance coverage to eligible retirees.[24] Retired employees can be eligible for an OPEB subsidy to cover insurance premiums, or they can have access to the state plans, whose year-to-year changes in premiums are, in general, more predictable than ACA exchange plans. Once retirees reach age 65, they are required to enroll in Medicare parts A and B and are automatically enrolled in an OptumRx Medicare Part D prescription drug plan. The percentage of the premium covered by the state or employer varies from tier to tier and position to position, so retirees may pay some or none of their plan’s monthly premium.

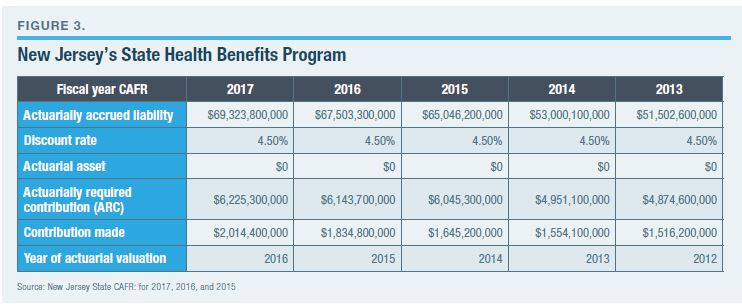

New Jersey operates its OPEB plans, state and municipal, on a pay-as-you-go basis, meaning that no assets are held in trust to cover future liabilities. The state’s net OPEB liability grew by nearly $18 billion from 2013 to 2017, reaching $69.3 billion (Figure 3); during this same period, normal costs rose by 33% and ARC rose by 28%. Unlike Connecticut and New York, New Jersey did not lower its discount rate to reflect the lower than historically normal returns on short-term investments.

New Jersey’s brutal budget battle in 2017 appears to have finally pushed the majority of the legislature and the newly elected governor, Phil Murphy, to get serious about the state’s long-term liabilities. In 2018, Murphy negotiated to move retirees from the School Employees Health Benefits Plan to Medicare Advantage, a move that mirrors Connecticut’s 2017 reforms. That reform is expected to save the state nearly $500 million over two years.[25] Like Connecticut’s, however, New Jersey’s reform does not address the high and rising costs of its employees’ platinum (as defined by ACA; platinum plans pay 90% of covered costs) health-care plans.

More OPEB reforms are necessary and probable in the near future. New Jersey Senate president Stephen Sweeney and Assembly Speaker Craig Coughlin have expressed an unwillingness to close the budget deficit through tax increases and, surprisingly, their intent to reduce New Jersey’s long-term retirement liabilities.[26] Sweeney has pushed a series of proposals developed by a panel of 25 policy experts that would reduce the cost of the state’s retirement benefits by about a third.[27] Key elements include reducing the state health-insurance plan from a platinum plan to a gold plan (which would pay 80% of covered costs), and moving some newly hired state employees to a hybrid pension system.[28]

Moving state employees to a gold plan would reduce the state’s OPEB liability in two ways. The first is by increasing the state employees’ cost-sharing from zero (in many cases) to about 20%. The second is by reducing the plan’s tax liability. Currently, employer-sponsored tax benefits function as a type of tax-sheltered income. However, this may change in 2022. ACA contained a provision called the “Cadillac tax” that taxes employer-sponsored tax benefits with annual premiums exceeding $10,200 a year, indexed by inflation. Plans are taxed at a rate of 40% of the amount exceeding the threshold. By switching from a platinum plan to a gold plan, New Jersey would likely eliminate this future liability.

New York City

The Big Apple has accrued a staggering net OPEB liability of $90 billion—larger, in fact, than the state’s $72 billion NYSHIP OPEB liability estimate. (The two estimates may be comparable, however, as New York State uses a slightly lower discount rate and New York City assumes a slightly higher rate of health-care price increases.)

New York City offers 11 health-insurance plans to active and non-Medicare-eligible retirees. The employer covers the full premium of some basic coverage plans while retirees bear additional costs for some others. (Additional benefits can be purchased as “riders.”) Retirees aged 65 or older can continue to use the city health plans as their primary coverage, with Medicare as their secondary coverage, or select to have Medicare as their primary. If a retiree selects Medicare as primary, the city can reimburse him for his Part B premium.

Like the state, New York City has six retirement tiers, ranging from tier 1 employees, hired before July 1, 1973, to tier 6 employees, hired after April 1, 2012. Vesting requirements vary, depending on tier and position, with earlier tiers allowing for more generous early retirement than later tiers. For example, tier 1 employees are able to retire at age 55 with full pension and health-care benefits, and at age 50 for physically demanding positions. Tier 6 employees can retire with full benefits at age 63, with a pension benefit penalty for early retirement between ages 55 and 63.

New York City’s actuarial reports are more detailed and complete than most state reports. In addition to providing a sensitivity analysis to changes in discount rates, the actuaries provide a sensitivity analysis for health-care cost trends. The city’s 2018 valuation highlights an important difference between OPEB and pension liabilities generally. Discount rates are arguably the most significant assumption for estimating pension costs, but health-care-cost trend rates are more important for most OPEB plans because most OPEB plans are run on a pay-as-you-go basis and thus use very low discount rates.

Between 2013 and 2017, New York City’s actuarially accrued OPEB liability grew by nearly $24 billion while the city’s assets grew by $3.3 billion, a net increase of $20.6 billion (Figure 4). The city also increased its contributions from $3.6 billion to $4.9 billion, increasing the funding ratio from 1.9% to 4.9%. Unlike state plans, New York City’s plan does not calculate an ARC, reflecting its decision to operate as a pay-as-you-go plan. However, New York City’s OPEB plans, compared with those of New York State, Connecticut, and New Jersey, appear to be the least sustainable and the least likely to be reformed in the short run.

The Challenge of OPEB Valuation

In both pension and OPEB valuations, actuarial accrued liabilities are presented as a point estimate of the present value of the state and municipality’s liability to current and future retirees. The estimates are based on assumptions about factors such as medical price inflation, health-care utilization, payroll growth, membership, and mortality rates. Each variable used to estimate the future OPEB obligation has a distribution of possible future values. In the aggregate, these assumptions form a distribution of possible outcomes for a state OPEB liability.

A point estimate of an OPEB liability is constructed from point estimates of each variable used in estimating the future liability. For example, over the past two decades, the chained consumer price index (C-CPI) for urban consumers, all items, was 1.85%, on average, with a standard deviation of 1.07%.[29] From this trend, it is reasonable to assume that there will be about 2% average inflation in the future, although there is a possibility that the Federal Reserve will increase its target rate. The same logic is applied to other variables, using the appropriate time frames for each variable, such as mortality, consumption, and prices, usually measured using experience studies. Using these averages, an actuary can construct a point estimate, the most likely liability based on historical trends. This is reported in actuarial valuations and CAFRs.

Point estimates give the impression that a government is liable for the amount stated. However, a government can be liable for the entire range of outcomes, especially when the promised benefits have strong legal or constitutional protections. In recent years, some pension actuaries have adopted sensitivity analyses, sometimes called “stress tests.” While some sensitivity analyses are very comprehensive, most are conducted by presenting three numbers: the average; the average with a 1% lower discount rate; and the average with a 1% higher discount rate.

The movement toward stress tests, particularly comprehensive stress tests that account for all variables, is vital for improving liability management and the political discussion about liabilities. However, if the benefits promised by a government to its employees are protected by extremely strong legal barriers, the upper limit of the range of possibilities is the most important figure, as the state must be prepared to meet that obligation under almost all foreseeable conditions. This is often calculated by applying a “risk-free” discount rate or discounting by the interest rate of the U.S. government’s recently issued bonds, a proxy for its default risk.

Point estimates can also mask the asymmetry of a probability distribution. For example, average life expectancy dramatically improved in the past half-century, but the probabilities favor a small improvement over the next half-century. This places an upper limit on mortality assumptions for the calculation of pension liabilities.

Assumptions for OPEB liabilities are another matter. Variability can change over time because of declining rates of cigarette consumption, for example, or policy decisions, such as the ACA “Cadillac tax.” Variables with high variance can complicate predicting future outcomes, particularly when their average is used in generating a point estimate of a liability.

Prefunded OPEB and pension plans assume that most of their obligations will be met by investment returns—but these plans have gradually increased the variance of their investment returns over the past half-century, moving from a portfolio of primarily bonds toward a diverse array of stocks, bonds, and alternatives.[30] In the case of assumed investment returns, the same geometric average return can have dramatically different results, depending on the degree of variability and the sequence of high and low returns when cash flow is accounted for.

For example, in Figure 5, the future funding ratio of the City of Austin Employees’ Retirement System is projected using an average investment return of 7.5% with strong, weak, or average returns occurring early in the projection. The outcomes range from the city’s retirement system ending up overfunded by about 50% to ending up insolvent.

The assumptions used to construct OPEB liability estimates range from predictable, such as inflation, to the uncertain, such as health-care costs in the distant future. In addition to some variables being difficult to predict, some variables are beyond the control of the state or municipality. Potential future outcomes may even be rare or difficult to predict and may have an outsize impact on OPEB costs. OPEB benefits can be restructured to exclude the more difficult assumptions in order to produce more accurate estimates. Additionally, OPEB liability reporting can be improved by propagating the errors of each assumption to produce and present the range of probable costs.

It is not possible to construct an exhaustive and informative list of the possible out-of-sample outcomes that could significantly change a state or municipality’s net OPEB liability. This is partly because future events may be contingent on information that has not been generated and is unpredictable, and partly because estimating the probability of events that may occur only once is extremely difficult. However, hypothetical examples based on recent events can be illustrative of potential future changes to OPEB cost trends.

For example, New York State’s most recent actuarial valuation accounted for the implementation of the Cadillac tax, increasing its net OPEB liability. The Cadillac tax is a very narrow levy, targeted at platinum insurance plans. Over time, the choice of indexing the tax to inflation and the trend of health-care prices to increase faster than general inflation will cause more plans to fall under the tax. Relative to the early years after ACA was passed, this process will be accelerated because of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which updated the inflation measure from CPI to C-CPI. This has significant implications for the public sector, as the greater the difference between health-care inflation and C-CPI, the faster states and municipalities will develop a federal tax liability for their gold and platinum health-benefit plans, including OPEB plans.

Although major federal reforms are very rare, it is possible that a future tax or health-care reform act will do away with the tax preference entirely. In 2018, the exclusion of employer-paid (and employee-paid) health-insurance premiums from liability to the federal income tax is estimated to be the country’s largest socalled tax expenditure.[31] Between the rising tide of federal debt and calls for a public health-care option, this exclusion might end. For states and municipalities, this would dramatically increase the cost of benefits for active employees and OPEB-eligible retirees by taxing those benefits as compensation—as the public sector compensates employees through benefits at a much higher benefit-to-salary ratio than the private sector. Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, and, especially, New York City, where OPEB benefits are exceptionally generous compared with the rest of the country, would be the hardest hit.

The ACA also defined 10 “essential health benefits” (EHBs) to create a minimum benefits floor in the health-insurance market.[32] The reform was aimed primarily at individual and small employer policies, but it also affects larger plans. EHB mandates have an impact on an estimated 156 million Americans, primarily in the form of higher premiums (paid by employers and employees, and currently excluded from the federal income tax) to cover more benefits that may or may not apply to any given plan beneficiary.[33] EHBs could be expanded in the future in ways that could dramatically increase OPEB costs.

For example, what if a new treatment for type II diabetes is developed that cures, rather than manages, the disease? New treatments are often extremely expensive. Take the recently discovered treatments for hepatitis C, first made available in 2013.[34] For about 95% of cases, the new treatment cures hepatitis C with few adverse effects. Despite there being a cure, many people continue to struggle with the virus because the treatment can cost nearly $100,000, prompting insurers to deny the treatment for about 35.5% of people who are prescribed the drug.[35]

Type II diabetes and its precursor, prediabetes, affect a quarter of the U.S. population. In 2015, it was listed as the seventh leading cause of death. However, this understates the problem, as diabetes often contributes to heart, nerve, and kidney diseases.[36] If a cure were discovered, an extremely strong political will would mandate its coverage, regardless of cost, because of the human toll of the disease and its burden on Medicare and Medicaid. By promising coverage to retirees before Medicare eligibility, states and municipalities may bear the brunt of the cost, significantly increasing their OPEB liability.

Price trends, consumption trends, legal mandates, economic health, unexpected demographic shifts, and other key variables could shift costs higher or, less likely, lower. The impact of many of these variables on state and municipal government spending and taxes can be reduced or eliminated by phasing out OPEB plans or switching OPEBs from insurance coverage to a premium subsidy indexed to inflation. These changes would remove the need to estimate a liability or make the estimation far easier.

OPEB Reform

Ideally, public-sector OPEB would be phased out. This would remove the financial burden (and the potential threat to public services) from state and local government taxpayers and make benefits offered to government employees more similar to those of private-sector workers. If policymakers are unwilling or unable to do so, OPEB plans could be reformed in several ways to develop a sustainable retiree health-care benefit with predictable costs. These reforms include:

Winding down OPEB liabilities

For most state and local retirement systems, OPEB liabilities are relatively small, compared with pension obligations. These systems can wind down their obligations, and ultimately eliminate them, by phasing out OPEB benefits for new hires. For most professions, this can be accomplished by lifting the normal retirement age to 65 (when employees become Medicare-eligible), eliminating subsidies to Medicare supplemental insurance or Part B premiums, and offering early retirees access to the state health plan without subsidy, meaning that the retiree pays the premium. This would align public-sector benefits more closely with private-sector benefits.[37]

Instead of winding them down, Kansas (in 2016) and South Dakota (in 2014) wiped clean their OPEB liabilities in a single year by eliminating explicit and implicit OPEB subsidies.[38] This reform shifted the entire cost, as well as the risk, from the state to the retiree. Instead of a subsidy, Kansas’s and South Dakota’s retiree benefit is access to the state-sponsored health-insurance plans, meaning that retired employees pay the employer and employee share of the plan premium. For states and municipalities with relatively small OPEB liabilities, this reform can be made in a single year, reducing risks associated with the retiree benefit system.

Creating an OPEB/pension trade-off

While eliminating explicit and implicit OPEB subsidies removes state or municipal financial risk, governments that do not offer any health-care subsidy between early retirement and age 65 may inadvertently decrease the efficiency of their workforce and increase their pension liabilities. However, OPEB and pension benefits can be structured so that increased health-care costs are offset by an equal or greater decrease in pension costs. This would allow for states and municipalities to provide early retirement for professions that significantly benefit from a younger and/or more engaged workforce without increasing their liabilities.

In a survey conducted by the Pew Charitable Trust and the National Association of State Personnel Executives, state personnel directors were asked if retirement benefits had an impact on employee performance. Most declined to answer, but of the respondents who did, 81% reported that some employees continued to work—despite being disengaged—to maximize their retirement benefits.[39] Part of the problem is that pension plans often use the last three to five years of salary to calculate the retiree’s benefit, encouraging employees to stay at their highest position for as many years as possible, work overtime, and accrue unused vacation days. Additionally, some plans discourage early retirement with benefit penalties to reduce the possibility of there being more retirees than active workers. However, OPEB benefits can play an important role for employees who are deciding when to retire. The Pew report found that governments with less generous OPEB plans had more employees deferring early retirement because of the cost of health care before Medicare eligibility.

There are ways to reduce the numbers of disengaged employees and, potentially, improve pension solvency. For example, an explicit OPEB premium subsidy, indexed to inflation, balanced with an early retirement pension penalty, can reduce the barrier to early retirement while lowering the state’s net retirement benefit liability if the actuarial value of the pension penalty exceeds the explicit subsidy. Employees are likely to accept early retirement pension penalties greater than the OPEB benefit, resulting in net savings for a government, due to both nonmonetary benefits, such as being able to enjoy retirement during their more physically active years, and a bias in favor of the present as against the future. Furthermore, pension benefit formulas should use more years in determining the retiree’s benefit—a decade instead of three years would work—and exclude overtime and unused vacation from the calculation. These changes are commonly referred to as “anti-spiking.” With these changes, public employees would be able to retire earlier more comfortably, the state or municipality would reduce its retirement liabilities, and residents could benefit from better government services.

Provide explicit subsidies indexed to general inflation

For some states, it would be difficult to find the political will to phase out OPEB benefits entirely. In those cases, restructuring the benefit to limit the number of complex variables involved in estimating future liabilities is vital. For example, New Jersey has accreted obligations through decades of fiscal irresponsibility, such as making partial pension contributions, operating its OPEB plan on a pay-as-you-go basis, and issuing pension obligation bonds. The state is one of five with unfunded OPEB liabilities that exceed $10,000 per capita.[40] New Jersey also has the fifth worst-funded state-administered pension systems in the country (controlling for differences in discount rates).[41] Legislatures, governors, and policy advocates have struggled to implement OPEB reform.[42]

In 2015, the New Jersey Pension and Health Benefit Study Commission released a report detailing a path toward fiscal stability, releasing a supplementary report focused on health benefits a year later.[43] The report concluded that a massive overhaul of the state employee retirement benefit is necessary because “a state budget so burdened by employee benefits would not be able to weather a recession or permit the State to do what is necessary to promote the general welfare of its citizens.” The commission made a series of recommendations that closely align with existing retiree-benefit reform research, such as switching new hires from a traditional pension plan to a cash balance plan, reducing their assumed rate of return, and reducing the employee health-care benefit from platinum to gold plans.

In a supplemental report, the commission provided a detailed framework for reforming New Jersey’s state and local health plan, and using the savings accrued through OPEB reform to ease the projected increase in annual required pension contributions. For retirees, health-care coverage would change:

Over time, the Cadillac-tax threshold would likely become the lower, and thus selected, benchmark because it will be indexed to C-CPI starting in 2022.[45] As noted earlier, medical inflation has historically been higher and less predictable than general inflation. The benchmark would reduce the future cost of the plan if medical inflation continues to outpace C-CPI, and, more important, it would also increase the predictability of the OPEB liability. The state would be liable for a set amount of money per retiree under age 65 that would grow at an average rate of about 2%—barring a sea change in U.S. monetary policy.

This change would remove many of the more complex variables—health-care utilization, cost, innovation, and regulation—involved in estimating OPEB liabilities. The state would provide a sustainable benefit (with more easily predicted future costs) that employees could reasonably plan their retirement around.

An explicit subsidy, ending at age 65 and indexed to inflation, solves many of the challenges associated with OPEB liability estimation and budget planning. For states and municipalities that insist on providing an OPEB benefit, this type of subsidy would be ideal. However, it still generates a liability that must be accounted for; and year-to-year costs may be volatile without an associated, funded OPEB trust.

Prefunding an OPEB trust

Very few OPEB plans are prefunded, and very few of the prefunded plans are fully funded. In 2017, state OPEB plans stood at a staggeringly low 2.63% funding ratio.[46] Arizona had the best prefunded system, at 38%, using a risk-free rate, and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas did not have a funding ratio, as they do not offer a subsidy. The widespread practice of offering a subsidy without developing a fund to support that subsidy is deeply problematic.

Most pension plans switched to prefunding over the past five decades after experimenting with pay-as-you-go. Pay-as-you-go plans use annual employee and employer contributions to cover the current cost of the plan but do not set aside assets toward future costs. Usually, this results in annual costs that are 20%–40% of the annual required contribution to fully fund the plan. Thus, pay-as-you-go plans tend to accrue liabilities quickly; eventually, their annual required contributions begin to grow quickly as well. This method of liability management resulted in the first wave of pension crises, primarily in the private sector, in the 1960s. Congress passed the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) in 1974 to regulate private-sector pensions in the hopes of stemming future crises, outlining best practices that were partially adopted by the public sector.[47]

Prefunding provides a greater degree of stability in terms of benefit costs because it provides the employer with an asset base that can be used for smoothing unexpected changes in the plan’s estimated liabilities or asset performance. However, there are strong political and financial incentives against prefunding. The Pew Charitable Trust explains:

From this perspective, pay-as-you-go places OPEB benefits in a sort of limbo, where employers offer benefits in the hopes that they will be renegotiated by a future administration or legislature. But renegotiation may be impossible if the changes are struck down in court. This potential conflict played out in the Illinois Supreme Court in 2017, when Chicago city employees and retirees had a generous OPEB subsidy phased out, cutting the city’s annual OPEB costs by about 94%.[49]

The public employees contested the changes but lost in court. While the phaseout was necessary to right Chicago’s fiscal ship, public-sector workers had likely planned their retirement on the assumption that these benefits would continue to exist. Ideally, state and local governments should not offer an OPEB subsidy, or else they should fully prefund their OPEB subsidy to prevent these conflicts.

Institute a Medicare cutoff

At age 65, most OPEB plans either end or scale back to supplementing Medicare coverage. Thus, the majority of OPEB liabilities are accrued by early retirements. However, plans that extend beyond age 65 expose themselves to greater risks for the portion of the liability due after Medicare eligibility. Part of this is simply due to the liability extending further into the future, as time and volatility degrade the accuracy of estimates. If an OPEB plan does not already limit itself to early retirements, it can improve its stability and sustainability by doing so.

Conclusion

For most state and local governments, OPEB benefits represent a smaller liability relative to other obligations, such as pensions and bonded debt. However, OPEB liabilities involve complex variables that can render point estimates misleading and the future cost of the plan difficult, and potentially impossible, to know. State and local governments may inadvertently overpromise OPEB benefits to current employees, leading to a future budget crisis. These crises place governments in the unenviable position of either cutting benefits to the employees who have planned their retirement around the assumption that their health care will be subsidized, or cutting core government services.

However, budget crises stemming from retirement benefits can be mitigated by embracing reforms that reduce costs: by eliminating OPEB subsidies for health care; by balancing OPEB benefits with pension penalties; by increasing the predictability of OPEB obligations by providing a health-insurance premium subsidy indexed to inflation; by limiting OPEB benefits to retirees under the age of 65; or by some combination of these reforms, such as limiting OPEB subsidies to hazardous work and to retirees under age 65.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).