How Years of Policy Choices Enabled Microschooling to Thrive in Arizona

Forward

In this installment in our series on state-level policy and microschooling, Michael McShane explores how Arizona’s decades-long commitment to school diversification and choice laid the foundation for the state’s burgeoning microschooling community. Since the 1990s, Arizona has been among the nation’s leaders in policies that support the creation of new schools and that enable families to access an array of educational options. As a result, when the concept of microschooling took off nationally—and when the pandemic increased parental demand for non-district alternatives—Arizona was a natural fit; it had both a culture of school choice and innovation and a policy environment built for social entrepreneurs and reform-minded parents. McShane’s excellent paper dovetails with the others in this series, demonstrating that an array of policy choices made by state officials over the years—rules related to funding, chartering, online learning, homeschooling, and more—will largely determine whether microschooling can take root and bloom.

—Andy Smarick, Senior Fellow

Executive Summary

Microschools, small schools that educate five to 15 students, have been among the most interesting recent developments in the K–12 reform world. Neither homeschooling nor traditional schooling, they exist in a hard-to-classify space between formal and informal learning environments. They rose in popularity during the pandemic as families sought alternative educational options that could meet social-distancing recommendations. But what they offer in terms of personalization, community building, schedules, calendars, and the delivery of instruction will have appeal long after Covid recedes.

One of the most prominent microschooling networks, Prenda, was founded in 2018 in Mesa, Arizona’s third largest city. It has experienced dramatic growth largely because of the way it attracts parents like those interviewed for this paper. It is no coincidence that Prenda’s emergence and expansion took place in Arizona, which has been a national leader in education innovation for a generation. Arizona’s cultural and policy environment foster and promote experimentation, diversification, and parental choice. The state’s thriving charter-school sector—no state has a higher percentage of students in charters—has developed an expansive, varied set of choice-based public schools. For decades, Arizona’s traditional public schools have been part of the state’s open-enrollment system, making more than a thousand district-run schools part of a choice system. And Arizona has been a national leader on private-school choice, passing the nation’s first “education savings account” program and today, via an array of state programs, enabling more than 100,000 students to access nonpublic schools.

This paper explores microschooling in the Grand Canyon State through parent interviews, a review of decades of public-policy reform and K–12 political battles, and an assessment of student performance data. A key lesson—one that reform-minded advocates in other states should consider— is that one cannot understand microschooling in Arizona without understanding Arizona.

Taking the Leap

Sophia Ortega is a mother in Buckeye, Arizona. In January 2020, her two children were enrolled in a high-performing, well-known charter school. But she was not happy with the school.

Her boys are, in her words, “energetic, rambunctious, and smart,” but too frequently, in their school, the first two characteristics were in tension with the third. A friend who had already pulled her children out of school had heard about Prenda, a small but growing network of microschools. Though Sophia was skeptical, PrendaCon, a gathering of Prenda educators and families, was taking place in two days, so she and her friend decided to check it out.

Prenda founder Kelly Smith’s opening presentation had Sophia hooked. The core values of Prenda aligned with her beliefs about parenting and education. The structure of the school day and the educational environment were what she wanted for her children. She was still hesitant— this would be a new approach to schooling—but the pandemic and the challenges that she faced as a single mother juggling full-time work and two children learning at home persuaded her to take the leap.

In September 2020, she started as a guide (Prenda’s term for a teacher) in a microschool hosted in her friend’s house. That school now enrolls seven students, six boys and one girl, ranging from kindergarten to sixth grade.

On a typical day, students arrive at 9 a.m. and play for about 15 minutes. At 9:15, Sophia starts the “Morning Standup,” where children gather in an “awareness circle” to do deep breathing and center themselves before talking about their goals for the day. Students also have an opportunity to share anything they would like with the group.

From 9:30 to 11:15, students work through “Conquer,” a personalized learning curriculum, on their Chromebooks. The microschool has a sectional sofa and blankets, and students are allowed to work wherever they find it most comfortable. Sometimes, students want some space; other times, they practically stack themselves on top of one another. When they need assistance, Sophia is available, though she is just as likely to see students asking one another for help. Conquer covers math, language arts, reading, and writing.

After a snack break at 11:15, the second part of the day begins: “Create,” in which students pursue individual art projects. Prenda offers students a bank of options, but as they age, they can develop their own projects. Students have to identify what the purpose of the project is and plan all the steps. They can present to their classmates if they wish.

The students break for lunch, 12:45–1:30, with a bit of playtime at the end, and then enter the third component of the Prenda instructional model: “Collaborate.” In this module, which runs from 1:30 to 2:20, students work on group projects, particularly in science and social studies. One example from Sophia’s microschool was a project by fourth- and fifth-graders that tracked a day in the life of a Bedouin, the Arabic-speaking nomadic peoples of the Middle Eastern deserts. As a guide, Sophia works to “get them engaged” and “get them excited about leading their own learning,” as she puts it.

When I asked why she got involved with Prenda, Sophia highlighted the key values that anchor Prenda’s work: “Start with heart,” “Figure it out,” “Dare greatly,” “Foundation of trust,” and “Learning > comfort.” “Start with heart” really spoke to her; it matched her parenting style, and she thought that it was missing from her kids’ previous schools. But she also thinks that “a lot of kids are afraid to dare greatly.” Encouraging students to take risks helps them to “stay at their learning frontier” and grow into happier, more confident young people.

Seedbed of Microschooling

Arizona has been fertile ground for microschooling. The state’s demographics, policy, culture, and educational performance have combined to foster the emergence and growth of microschooling.

In a nutshell, Arizona had been a low-performing state in terms of educational outcomes, but it also had a fast-growing population. The state needed not only better educational outcomes but more schools to address growing enrollment. Given the state’s libertarian roots, policymakers decided to address these issues by experimenting aggressively with school choice. The proliferation of choice programs and the state’s light-touch approach to regulation spurred new school creation and acclimated the citizenry to a diversity of school options. Over time, positive student- achievement results bolstered public support for school choice, which helped lead, ultimately, to the passage of the nation’s first education savings accounts, which can serve as an engine for microschooling.

To those outside the state, Arizona’s approach to education reform over the last quarter-century has been a sort of Rorschach test. It’s either the unruly Wild West or a hotbed of dynamism and family empowerment. Some critics say that Arizona is an example of underinvestment and underperformance—pointing to its relatively low per-pupil spending levels and test scores; they say that its lightly regulated choice sector is ripe for abuse. The state’s advocates, however, have argued that Arizona gets more educational bang for taxpayers’ bucks than other states and that its policy innovations prove the benefits of getting bureaucracies out of the way and putting educational entrepreneurs and parents in the driver’s seat. Though these narratives are clearly at odds, both result from Arizona’s particular history and policy choices.

Probably no one has dug deeper into Arizona’s school performance data than Matthew Ladner, director of the Arizona Center for Student Opportunity at the Arizona Charter School Association. The story he tells is encouraging. In 1980, Arizona was a small but rapidly growing low-income and predominantly white state. When the first National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores come out in 1990, “the news was not flattering” for Arizona, as Ladner puts it. In most of the tests administered, Arizona was often among the bottom five states.

But Arizona’s population was growing. Retirees and families with children were moving in for the open space, good weather, low taxes, and low cost of living. This produced an hourglass-shaped age population distribution, with a disproportionate number of older and younger residents. [1] But the state’s libertarian roots and an influx of seniors disinclined to support more spending on schools kept Arizona at the bottom of the nation’s education-expenditure list.

In 1994, Arizona legislators Tom Patterson, Lisa Graham Keegan, and Armando Ruiz led the push for school choice. That year, the legislature passed charter-school and open-enrollment laws that placed Arizona on the path to becoming one of the most choice-friendly states in the nation. In 1997, a scholarship tax-credit program was passed; in 2011, a pathbreaking education savings account (ESA) program was created as well.

Prior to the open-enrollment and charter-school laws, public school students attended their local, geographically assigned public school. Afterward, students could choose from traditional public schools in other districts and the rapidly growing charter-school sector. With the subsequent generation of choice programs, private schools became more accessible as well. If a family qualified for one of the several private-school choice programs, state financial assistance would help cover tuition costs.

But in 2011, the state expanded choice even further, laying the groundwork for microschooling and other types of innovative models. Private-school choice, as originally conceived, helped families afford the costs associated with attending a traditional, brick-and-mortar private school. That is, state aid acted like a scholarship. But Arizona’s passage of ESAs created flexible-use spending accounts; families could divide this aid among several providers—not just spend the money at one private school. A family could use a portion for tuition, a portion for tutoring or physical therapy, and so on. This approach enabled a middle- or low-income Arizona family to customize a child’s education in ways that affluent families could.

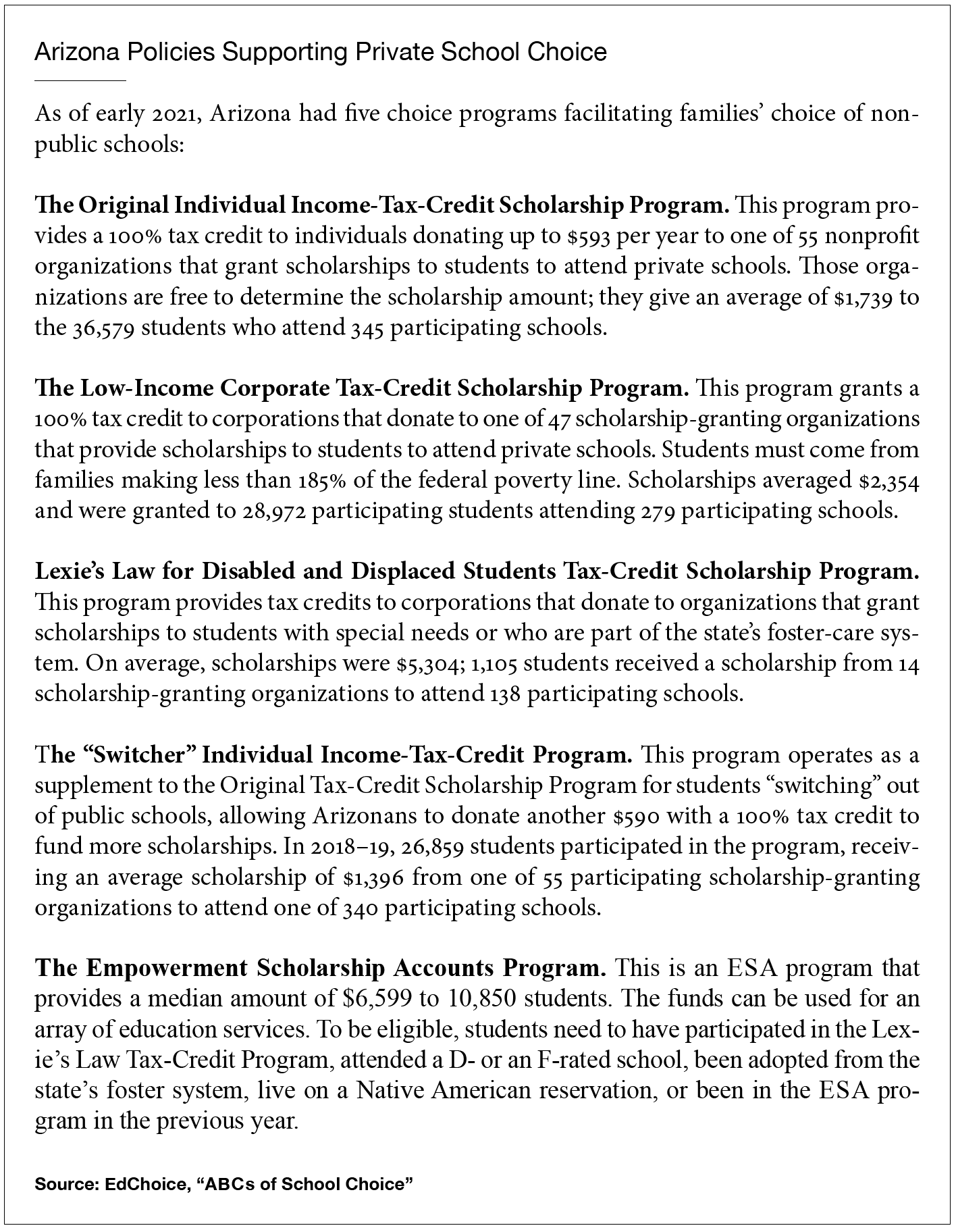

These programs are popular. According to the Morning Consult / EdChoice Public Opinion Tracker, 63% of Arizonans and 80% of Arizona parents support ESAs; 56% of Arizona citizens and 70% percent of Arizona parents support school vouchers, and 60% of Arizona citizens and 71% of parents support charter schools. [2] Though Arizona has a large percentage of students in charter schools, as Ladner has documented, the majority of students exercising school choice in Arizona have been open-enrollment students within the traditional public school system. They have outnumbered charter-school students almost 2 to 1. And, according to EdChoice’s ABCs of School Choice, 104,365 students participated in one of Arizona’s five private-school choice programs in 2020. [3]

Arizona has developed a permissive mentality when it comes to school choice. Rather than tightly regulating—and stultifying—school creation and diversification, it has taken what Ladner calls a “Let 1,000 flowers bloom” approach. According to a 2021 report by Benjamin Scafidi and Eric Wearne of Kennesaw State University, Arizona ranked second in the nation in the percentage of students enrolled in charter schools and in the percentage of students who have a charter school in their zip code (behind the District of Columbia). [4] According to Ladner, the state’s minimalistic regulatory approach to new school creation—“if the law doesn’t say that you can’t, then you can”—has helped cultivate a culture in which parents feel that “if you don’t like your options, start your own school.”

The state’s favorable views about choice have likely been strengthened by the heartening student- achievement results. Using data from the Stanford University Opportunity Project, Ladner argues that Maricopa County, the largest county in the state, showed student test-score growth that was 19% higher than the national average, the best among large urban counties in the nation. But it wasn’t just Maricopa; every county in the state, except one, had above-average student academic growth. [5] In total, these results put Arizona at the top of the pack among states in the Opportunity Project’s database when it comes to the rate of academic growth for all students and for low-income students specifically. [6] A rising tide had lifted all boats and moved Arizona from a very low-performing state to one firmly in the middle of the performance pack—and at substantially lower cost than most other states.

Research on charter schools helps explain this. In a 2015 article, Matthew Chingos and Martin West looked at charter-school performance in Arizona from 2006 to 2012: “On average, charter schools at every grade level have been modestly less effective than TPS (traditional public schools) in raising student achievement in some subjects. But charter schools that closed during this period have been lower performing than schools that remained open, a pattern that is not evident in the traditional public sector.” [7] In short, in Arizona, failing charter schools are shuttered. In a 2016 study, Deven Carlson and Stéphane Lavertu showed the positive achievement effects that such closures promote. Using data from Ohio, they found that “closing low-performing charter schools eventually yields achievement gains of around 0.2–0.3 standard deviations in reading and math for students attending these schools at the time they were identified for closure.” [8] According to data from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, between the 2017–18 and 2018–19 school years, Arizona closed 13 charters and opened 16 new ones. [9] Unsurprisingly, a sector that is opening new schools and closing its lower-performing schools will, slowly but surely, improve.

Shoots in the Desert

Laura Player, a mother in Mesa, Arizona, was drawn to Prenda while watching a school board meeting in spring 2020. She has a daughter who was diagnosed with autism and had been thriving at home. Laura thought that Prenda might be a good option. She had been disappointed with the local school district’s response to the pandemic and was encouraged to see Prenda presenting to the school board about a potential partnership. According to board documents, the plan was for students to remain enrolled in the Mesa district while participating in a Prenda- style learning environment. District-employed educators would serve as students’ official “teacher of record” and would “mentor” a set of about 25 students, monitoring progress and completing their report cards. As the presentation from the district to the board stated, this would give families a choice while keeping them enrolled in the district. As a bullet in the PowerPoint presentation put it, this approach would give Mesa the chance to partner with Prenda rather than compete with it. [10]

The superintendent was supportive and presented the opportunity to the board, which summarily rejected it. According to a local left-of-center news site, the local teachers union “flooded” the board with negative comments. Board members grilled Kelly Smith about the racial makeup of Prenda’s current student body and described as “unconscionable” the desire to recover students who had left the district for charter schools. [11]

This told Laura two things. First, the district was willing to make decisions based on what the union wanted instead of what would be best for children like hers. Second, she inferred that the district would not go back to in-person schooling in the fall. The teachers union had made it clear that teachers did not want to return to school in person, going so far as to host a funeral procession that culminated in teachers signing their own obituaries. [12] If unions were calling the shots with respect to the Prenda partnership, Laura predicted that the same would be true about a return to in-person schooling. She pulled her kids out of school that week.

Initially, she just wanted to find a Prenda microschool for her children but soon realized that if she became a guide herself, “that is ten more kids that can do Prenda.” As she put it, “I’m the kind of person who is two feet in,” so she advertised herself on social media and participated in Prenda’s feature called “The Map,” which helps match families to schools in their areas. Her microschool now has 10 students: her three children and seven others.

Laura loves being a Prenda guide. On a personal level, she says, “I am using all the skills I’ve ever learned.” But her real joy comes from seeing the development of her students. “I have seen so much growth in the children,” she said. “They haven’t just grown academically; they’ve grown emotionally.” She spoke about one of her students who was initially prone to outbursts and would refuse to do schoolwork. Slowly, over the course of the year, the core Prenda values started to work. She would help him understand that the things that frustrated him were the “mountains to climb.” The lessons at the start and end of each day to help students regulate their emotions helped as well. She also believes that Prenda’s personalized learning platform allows a student to work, for instance, at a ninth-grade level in math, a sixth-grade level in reading, and a fourth-grade level in grammar, all in the same day keeps students challenged and engaged.

Laura sees this in her own children. She was concerned that her daughter, an eighth-grader who excelled in the traditional school model, might not do as well in Prenda’s untraditional environment. But her daughter has thrived. “She has learned to learn for herself, not because she is required to.” What’s more, because Laura is the teacher, it has improved their relationship.

Before, when her children would come home from school, they would have the typical “Well, what did you do at school today?” conversation. Her kids would say one or two things, and that would be the end of it. Now they have daylong conversations about learning.

The Pandemic

As Sophia and Laura attest, the pandemic accelerated the growth of this already-expanding sector. Prenda’s enrollment doubled over the lockdown summer of 2020, with the Arizona Mirror reporting that the number of Prenda schools jumped from 126 to 264. [13]

According to my discussions with microschooling families and educators, there is a sense that traditional public schools in Arizona responded poorly to the pandemic. The general consensus was that while it felt necessary to close schools in spring 2020 (in the first months of the pandemic), schools needed to have a strong plan to start the new school year in the fall. Those plans didn’t materialize or were deemed to be insufficient. Communication was poor. Trust levels were low. Those who listened in to board meetings or Zoom discussions of reopening plans did not feel as though the needs of their children were being prioritized. Schools moved too slowly, stuck too closely to old routines, and seemed unable to appreciate the massive costs that months of diminished learning would exact on children.

The traditional public schools’ poor pandemic response was, for many parents, emblematic of larger problems with the system. System administrators facing competing demands could always be pressured to make decisions that de-prioritized student needs in favor of other considerations, like costs, union priorities, or political winds. Parents often feel as though they have little ability to influence district behavior on textbook adoption, school schedules, and the introduction of new technologies; their sense of powerlessness when it came to reopening plans was not entirely new.

In some ways, microschools were a perfect response to the pandemic. With such small enrollments, they were better able to comply with local occupancy and social-distancing requirements. They were better able to be flexible about where they met, how they structured their schedules, and how they engaged with families.

But perhaps more than anything, the pandemic lowered the cost of experimentation. When schools are basically meeting students’ needs—even if they are not excelling—it is risky to try something new. But with schools entirely closed and seemingly not likely to fully reopen, the cost-benefit analysis changes.

In his landmark work Diffusion of Innovations, Everett Rogers categorized the adopters of new innovations along a continuum. The first small group of adopters are “innovators,” who love new things and are willing to take chances on new technologies and new experiences. They don’t mind having to troubleshoot problems and are comfortable with bugs and hiccups. The next group are “early adopters,” who are a bit more cautious but are still on the leading edge of new things. A larger swath of people are part of the “early majority”; before adopting something new, they want more evidence of its success. Rogers also identifies the “late majority” and the “laggards” who are significantly skeptical of new technologies and products. [14]

Rogers’s categories are helpful for understanding who is adopting microschooling in Arizona— as well as when and why they are doing so. Kelly Smith and the first families that he recruited were clearly innovators. They were willing to push the boats out without a clear plan; they worked to build Prenda as their children were experiencing it. After three years, and with a pandemic-aided growth spurt, Prenda is now probably in the realm of early adopters; if it continues to succeed, it will attract more initially skeptical observers. The question may become: How far across the continuum can Prenda reach?

To the innovators, the late majority and laggards may seem like head-in-the-sand Luddites who slow progress. But education policy has seen fad after fad generate great fanfare and then fail to live up to the hype. Skepticism is warranted. Prudence suggests that more experimentation, more course corrections, and more assessments are in order before going to scale.

But the right types of policies have enabled microschooling to take off in Arizona, and the right types of policies will enable it to evolve and improve.

Policy

Despite its culture of innovation and freedom, microschooling’s growth in Arizona relied on the specifics of its public policy landscape. Two policies, in particular, have been essential: flexibility in online chartering and ESAs. These policies should be considered closely by those in other states interested in advancing microschooling.

“Online” Charter Schools

When Prenda makes its pitch to parents, a major selling point is that it is free for students to participate. But how can a private program with 10 or fewer students per classroom and hours of hands-on projects be free of charge? Where does the funding come from?

The answer is clever and instructive. Prenda itself is not a school but a vendor. In most instances, students attending an Arizona Prenda microschool are actually enrolled in a school that has contracted with Prenda to provide its services. Some districts have hired Prenda to operate “schools within schools,” but the major partner for Prenda has been the Sequoia Charter School, a nonprofit network of both in-person and online charter schools.

Prenda students enroll in Sequoia and take all the state tests (per the state’s charter-school law) and have their results count toward Sequoia’s overall scores for the purposes of public accountability. But these students physically attend class in a microschool environment. That puts the education side of the operation under the aegis of the state department of education. But the physical Prenda centers are regulated as a kind of in-home child-care operation. That puts them under the administration of the state department of health services. Whereas schools are required to maintain expensive infrastructure—from wheelchair ramps to fire-suppressing sprinkler systems— at-home child-care centers need only follow basic and essential health and safety rules. That is a better and more logical fit for a Prenda location that has a half-dozen or so students, like a small child-care center—not 500 students, like a traditional public elementary school.

This model provides interesting lessons for online charter-school policy around the country. It is no secret that in many places, the performance of online charter schools has been underwhelming. A 2015 report from Stanford’s CREDO research center studied 158 online charter schools in 17 states and found that students performed 0.25 standard deviations worse in math and 0.10 standard deviations worse in reading than did students in traditional public schools (equivalent to 180 and 72 days of lost learning, respectively). [14] These are discouraging findings, but many students whose families choose online charter schools were likely already struggling in traditional public schools.

Prenda, as well as microschools more broadly, offers a halfway point between online learning and traditional schooling. This innovation leverages the personalized instructional software that allows students to progress at their own speed and work at different levels in different subjects, based on what they know and what they are able to do. At the same time, it provides a smallschool environment, including the ability to interact with other students, a sense of community, and support from one or more dedicated educators. It also gives them the chance to work on supervised projects in art, science, and social studies, keeping students engaged and helping them apply what they are learning. That is hard to do when students are working alone in an online environment.

Other states with substantial online student enrollment should think about creating in-person learning environments where students are still working through their online program but with in-person supports. For the students who thrive working alone at home in an online environment, nothing will need to change. But given that some online students would like the additional community and support provided by a microschool, this could be a valuable addition to the state’s portfolio of education options.

Education Savings Accounts

Arizona was the first state in America to pass an education savings account program. Modeled on health savings accounts, ESAs put money in a restricted-use fund for parents to spend on educational products and providers. Arizona maintains a list of approved providers that meet the definitions of goods and services allowed under the language of the program. The state uses the online ClassWallet platform to administer the program. Vendors and families log into Class- Wallet and connect with one another; ClassWallet handles payments and other administrative matters. Simply opening the state’s website for the ESA program shows hundreds of approved providers for curriculum, tutoring, and private schools.

One of the most interesting Prenda schools is funded through students participating in the ESA program. The San Carlos Micro School is located on the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation. Native American students are eligible for the ESA program, and they can use those funds to cover their tuition at the school, which advertises small class sizes, project-based learning, classical history, the Socratic method, arts and crafts, and field trips. Perhaps more important, it provides an opportunity outside the local traditional public school district. In the 2018–19 school year (the most recent year for which we have data), 85% of students in that district performed in the “minimally proficient” category in English language arts on the Arizona AZMerit state 3–8 exams, the lowest of the state’s four performance categories. Only 5% of students scored above the proficiency line in reading, and only 6% did so in math. [16] While test scores aren’t everything, those numbers are shockingly low.

Microschools and ESAs are a match made in heaven. ESAs provide a level of flexibility that even other forms of private-school-choice programs cannot. School voucher programs and tuition tax-credit scholarship programs have to be exchanged as a single unit at one educational provider. ESAs, on the other hand, can pay for tuition at a school (provided the cost is low enough) and can also be spent on supplemental resources, interventions, and providers that can round out a student’s education. So if students at a microschool don’t have access to foreign language options, they could find another provider and use ESA dollars to pay for it.

A Preview of Coming Attractions

With more and more families nationwide expressing support for school choice, Arizona might offer a glimpse into the future. It has led the way in public policies that foster the development of new educational options.

What can other states do to follow Arizona’s lead? Two policy approaches stand out. First, as described in depth here, states need to provide flexible-use funding so that families can access an array of alternative educational options. Second, states need to get rid of regulatory burdens that hinder the creation of new models. Does the state, for example, have regulations for the length of the school day, the length of the school year, or the subjects that must be taught—and how and when? Though private schools and homeschools are thought to be largely free of state rules, they can be quite heavily regulated by state education agencies and other departments.

Must teachers be licensed by the state? To be licensed, must they have a degree from a recognized teacher preparation program? Most microschools are recruiting nontraditional teachers, so requiring traditional licensure could be a major obstacle.

Do students receive course credit based on seat time—the number of days or hours spent in a particular class? If so, that presents problems for schools that use alternative schedules or give course credit to students who demonstrate subject mastery regardless of the amount of time spent on the material.

Will state education agencies classify microschools as full-fledged schools, thereby saddling them with burdensome infrastructure requirements?

Any of these regulations could thwart the growth of microschools. Ending or relaxing such rules generally, or providing carve-outs for innovative school models, will be key.

Politically, as we saw in Mesa, forces are aligning against microschools, even when they want to work within the traditional public system. Some vested interests that value the traditional model of schooling or established policies related to teachers and administrators are opposed to microschooling. They see microschooling as a threat to regular routines, funding streams, preparation programs, and more.

Even in a favorable political environment, scaling microschooling is challenging; indeed, “scaled-up microschooling” sounds like an oxymoron. To reach 1,000 students, a charter-school network might need two schools; a microschool network might need 100 schools. A traditional school might need four teachers to serve 100 students; a microschool might need 10 teachers. If traditional teacher-training programs prepare teachers for traditional schools, where will microschools find high-quality teachers suited for this atypical learning environment? If parents like microschools because of the personalized environment and lack of bureaucracy, what happens when a central office oversees 20 microschools?

Families and social entrepreneurs can find solutions for such challenges over time. The right kinds of policies will help facilitate that work. The wrong kinds of policies could make it all but impossible. Though the future of microschooling in Arizona is still uncertain, the state has shown how this movement can be fostered in its early days. If microschooling does grow around the country, Arizona’s example will deserve more than a little credit.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).