Overcoming Exclusionary Zoning: What New York State Should Do

The commuter suburbs within New York State need state legislation to overcome a legacy of restrictive zoning that prevents New York City workers as well as workers in the suburbs, from finding convenient and affordable housing. This report looks at the seven counties that are in a special taxing district providing financial support for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority but not in New York City: Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester, Putnam, Dutchess, Rockland, and Orange. In these counties, zoning authority is dispersed to numerous local governments, many of which perceive an interest in avoiding shouldering the infrastructure and service costs associated with population growth. Without a solution at the state level, housing construction in these counties has been falling, not rising, while employment has increased in the past decade, exacerbating already-tight housing conditions.

Legislation is currently under consideration in Albany that can address the suburbs’ chronic failure to construct new housing. These proposals have promising elements but can be improved. One proposal, by Governor Andrew Cuomo, would provide an expedited process for review of zoning applications that provide for new housing and specify developer payments to communities that approve new housing, in order to offset added costs. It could be improved by incorporating provisions already adopted in Massachusetts, where similar issues exist in the Boston metropolitan area. These provisions include a requirement for each community to enact a multifamily zoning district and a builder’s remedy that creates an avenue of appeal to a higher level of government for applicants that are unsuccessful at the municipal level.

A second proposal would require localities to permit Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), which are second units on lots currently occupied by single-family homes. ADUs can be attractive investments for homeowners, but the legislation misguidedly imposes strict conditions on lease renewals and evictions of tenants that would likely deter many property owners from constructing such units. More thoughtful versions of these two proposals could represent substantial progress in solving the suburbs’ long-standing housing shortage.

Introduction

New York State has long failed to build enough housing to meet the needs of its population. This failure, especially in the New York City metropolitan area, represents an ongoing threat to the economic recovery and future growth of the city and the state.

State legislation is necessary to overcome the unwillingness of local governments to make an appropriate contribution to an overall solution to the housing scarcity problem. Such legislation should make a distinction between New York City and its suburbs. The city’s failure is political, not institutional;[1] its unified five-county government has sufficient land-use planning and regulatory authority to solve the city’s housing problems. Since 1936, the city charter has provided for a City Planning Commission and a Department of City Planning under mayoral control, charged with planning for orderly growth and development. The city has the tools it needs; action is a matter of political leadership and successful coalition-building.

The failures of the metropolitan area’s suburban counties, however, are institutional: decentralized land-use planning and regulation mean that no governmental entity looks at, or has responsibility for, regional or even countywide needs. Private organizations such as the Regional Plan Association (RPA) try to fill this gap but have only the power of exhortation. Up to the 2021 legislative session, neither Governor Andrew Cuomo nor the members of the state assembly or senate had shown interest in the types of measures debated in—and, in many cases, adopted by—other states that limit the ability of localities to enact exclusionary zoning that chokes off new housing construction.

That situation has now changed. The governor has introduced legislation that acknowledges the state’s role in solving the suburban housing shortage. Concurrently, two state legislators have introduced legislation to require localities in the state to permit accessory dwelling units (ADUs)—second units on the same lot as a primary single-family residence.

This report focuses, as does the governor’s proposal, on the seven counties outside New York City but within the New York Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District, where a special payroll tax is levied to support the Metropolitan Transportation Authority: Dutchess, Nassau, Orange, Putnam, Rockland, Suffolk, and Westchester. First, the paper examines the constrained housing conditions, particularly as they affect renters, in these counties. Second, it looks at past attempts to frame solutions and suggests some additional considerations that would locate housing closer to arterial roads and job concentrations as well as commuter rail. Third, it assesses the current legislative proposals and comparable efforts in other states. Finally, it makes recommendations for improved legislation that can enable more construction of needed housing in New York City suburbs.

Suburban Housing Constraints

As the Covid-19 pandemic starkly revealed, even affluent counties such as the New York City suburbs depend on a large force of lower-paid service workers to support industries such as health care, retail, hospitality, and food service. To the extent that these workers can find housing within the counties where they work, it is likely to be rentals. Such housing has long been in scarce supply and has become more so over time, as shown in Figure 1, which compares five-year American Community Survey data for 2006–10 with 2015–19. In each county, median rent rose faster than the rate of inflation.[2] In every county, a measure of housing unaffordability called “rent burden”—the percentage of households paying more than 30% of their income on rent—stood at 54% or higher in 2015–19, the latest period available. Rent burden was almost as high in 2006–10.

The increase in inflation-adjusted rents and continuing high rent burden are indicators of housing scarcity for suburban residents whose incomes are too low to be able to buy a home. While high rents could be alleviated by increased new housing construction, the opposite is happening in New York’s suburbs. Comparing the 2001–08 and the 2009–18 periods, a NYC Department of City Planning study found that average annual new housing permits declined by about 60% on Long Island (Nassau and Suffolk), from 5,000 to 2,000 units per year, and by about half in the Hudson Valley, from about 6,000 to 3,000 units a year.[3]

The increase in inflation-adjusted rents and continuing high rent burden are indicators of housing scarcity for suburban residents whose incomes are too low to be able to buy a home. While high rents could be alleviated by increased new housing construction, the opposite is happening in New York’s suburbs. Comparing the 2001–08 and the 2009–18 periods, a NYC Department of City Planning study found that average annual new housing permits declined by about 60% on Long Island (Nassau and Suffolk), from 5,000 to 2,000 units per year, and by about half in the Hudson Valley, from about 6,000 to 3,000 units a year.[3]

The failure to supply enough rental housing has economic implications, as a 2018 report on Long Island described:

Workers and Commuting Patterns in the New York City Suburbs

Researchers who look at the shortage of housing in the New York City suburbs have consistently advocated for zoning reform. According to an RPA report:

The types of development that produce these kinds of neighborhoods [are] generally known as Transit-Oriented Development—or TOD. TOD can encompass many types of buildings—ranging from neighborhood developments like townhomes and garden apartments, to small but bustling village downtowns, to major job and economic centers. What they have in common is proximity to transit, a pedestrian-oriented nature, and the density needed to support the economy and community that are necessary for healthy and livable neighborhoods.[5]

This report accepts RPA’s definition of Transit-Oriented Development as a desirable outcome of suburban zoning reform. Since the vacant land suitable for single-family detached homes has largely been used, more housing means more density. Dense communities can provide employment and many services within walking distance and support transit for additional job opportunities and other trips, thus reducing vehicular usage and allowing residents to own fewer cars.

The RPA report focuses on building housing in proximity to commuter rail stations. It found that, of the New York region’s commuter rail stations studied that have infrastructure to support multifamily housing development (in the surrounding area), fewer than half had zoning that supported such development.[6]The governor’s legislative proposal—which, as discussed below, also focuses on areas around commuter rail stations—was likely influenced by the RPA report.

Development near rail transit is certainly part of the necessary picture: commuter rail in New York’s MTA region is a radial system that takes commuters into New York City’s central business districts. These commuters tend to have higher than average incomes for their counties.[7] Building large amounts of new housing near suburban train stations would likely boost the numbers of such workers living in the suburbs and take the pressure off New York City’s constrained housing stock—which has been the experience of new housing in transit-accessible locations in northern New Jersey.[8] This would allow New York City’s central business districts to add more jobs and benefit the state government’s finances by increasing tax revenues.

However, commuter rail is not the whole picture. In addition to more housing near train stations, suburban counties need more housing in proximity to bus-served locations and employment concentrations. New housing in the last two types of locations may be more likely to benefit local service workers rather than New York City commuters. As shown in Figure 2, the 1.8 million average annual wage and salary jobs in the seven counties in 2019 were concentrated in Nassau, Suffolk, and Westchester—these three counties accounted for 81% of employment in all seven counties. Jobs were also concentrated in four large industry groups: trade, transportation, and utilities; professional and business services; education and health services; and leisure and hospitality, which together constituted 74% of all jobs. While trade is in decline, the other three industry groups also account for more than 100% of the employment gains between the cyclical peak of 2008 and the most recent peak in 2019 (before the pandemic-induced recession), offsetting the job losses in trade and other declining industry groups.

Employers in these large industry groups are concentrated in traditional downtown areas but also in campus settings and office parks distant from commuter rail stations. Often, such areas are designed for auto commuting and difficult to access by public transportation from the dispersed locations where the workforce lives. Another form of transit-oriented development, in addition to those cited in the RPA report, would place new housing in proximity to these employment concentrations, enabling workers to commute by walking, bicycling, or a short bus ride.

Employers in these large industry groups are concentrated in traditional downtown areas but also in campus settings and office parks distant from commuter rail stations. Often, such areas are designed for auto commuting and difficult to access by public transportation from the dispersed locations where the workforce lives. Another form of transit-oriented development, in addition to those cited in the RPA report, would place new housing in proximity to these employment concentrations, enabling workers to commute by walking, bicycling, or a short bus ride.

The profile of suburban county workers is very different from that of county residents; fewer have a bachelor’s degree or higher, or some college, or an associate’s degree. Educational attainment can be considered a proxy for the likelihood that a county worker will be able to earn a salary high enough to purchase a home in expensive suburban markets. Figure 3 shows incounty private jobs with educational attainment for workers age 30 or over, for the second quarter of 2018: 14% of those who work in the seven counties have less than a high school diploma, and 23% have a high school diploma or equivalent. These percentages vary little for the individual counties. Twenty-nine percent of county workers have some college or an associate’s degree. The lower income of workers with less than a college diploma, in short, makes them more likely to depend on the availability of rental housing to live in the county where they work.

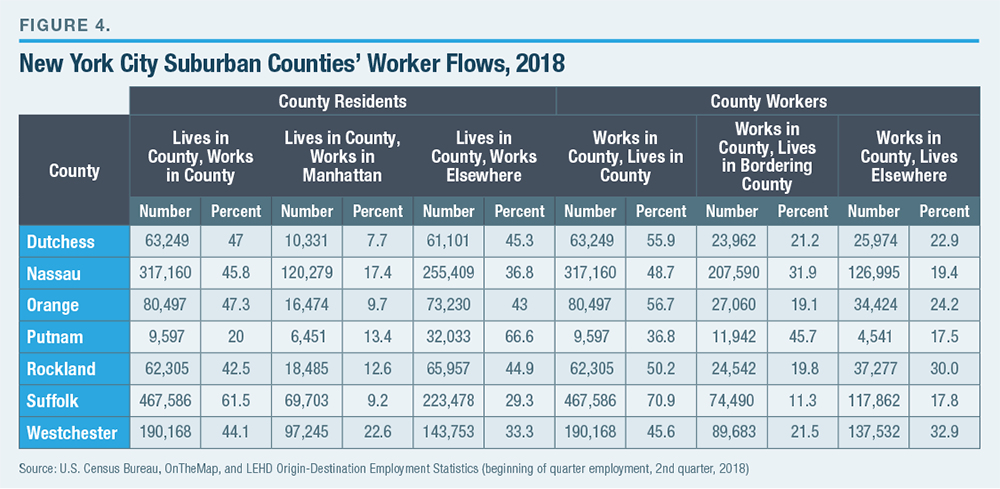

Because of this profile, as well as the suburban counties’ constrained supply of housing, these counties import workers from other counties—although, in each county, the largest share of in-county workers live in the county. In Suffolk, for example, more than 70% of its county workers live in-county, thanks to its geographic isolation. Elsewhere, the share of workers who live in the county where they work ranges from a low of 36.8% in Putnam to a high of 56.7% in Orange (Figure 4). Nassau has an unusually high percentage of workers living in a bordering county (either Queens or Suffolk)—31.9%. For most of the other suburban counties, this figure for workers living in a bordering county is about 20%. Suffolk is lower, and Putnam is higher. The figures for commuting from a more distant county vary from about 20% to 30%.

Because of this profile, as well as the suburban counties’ constrained supply of housing, these counties import workers from other counties—although, in each county, the largest share of in-county workers live in the county. In Suffolk, for example, more than 70% of its county workers live in-county, thanks to its geographic isolation. Elsewhere, the share of workers who live in the county where they work ranges from a low of 36.8% in Putnam to a high of 56.7% in Orange (Figure 4). Nassau has an unusually high percentage of workers living in a bordering county (either Queens or Suffolk)—31.9%. For most of the other suburban counties, this figure for workers living in a bordering county is about 20%. Suffolk is lower, and Putnam is higher. The figures for commuting from a more distant county vary from about 20% to 30%.

The seven counties tend to have fewer people working in the county than resident workers overall, so the same group of workers both residing and working in Nassau County represents 48.7% of people working in the county but 45.8% of residents who are working. Nassau and Westchester have the largest shares of residents working in Manhattan—17.4% and 22.6%, respectively—and these are the workers for whom living in proximity to a commuter rail station is likely to be most attractive.

The seven counties tend to have fewer people working in the county than resident workers overall, so the same group of workers both residing and working in Nassau County represents 48.7% of people working in the county but 45.8% of residents who are working. Nassau and Westchester have the largest shares of residents working in Manhattan—17.4% and 22.6%, respectively—and these are the workers for whom living in proximity to a commuter rail station is likely to be most attractive.

In sum, New York’s suburban counties rely on large numbers of relatively lower-paid workers, and these workers often find housing that they can afford outside the county where they work. It’s likely that many would like to shorten their commutes but do not find that to be possible. Suburban counties need more housing overall, as well as more of the types of housing that provide units that are relatively less expensive to rent—second units in heretofore single-family homes, attached homes, small multifamily buildings, garden apartments, and midrise apartment buildings. Suburban communities have such housing, often built decades ago when zoning was more permissive, but not enough to provide an adequate supply of rental housing at a range of rents affordable to most working households.

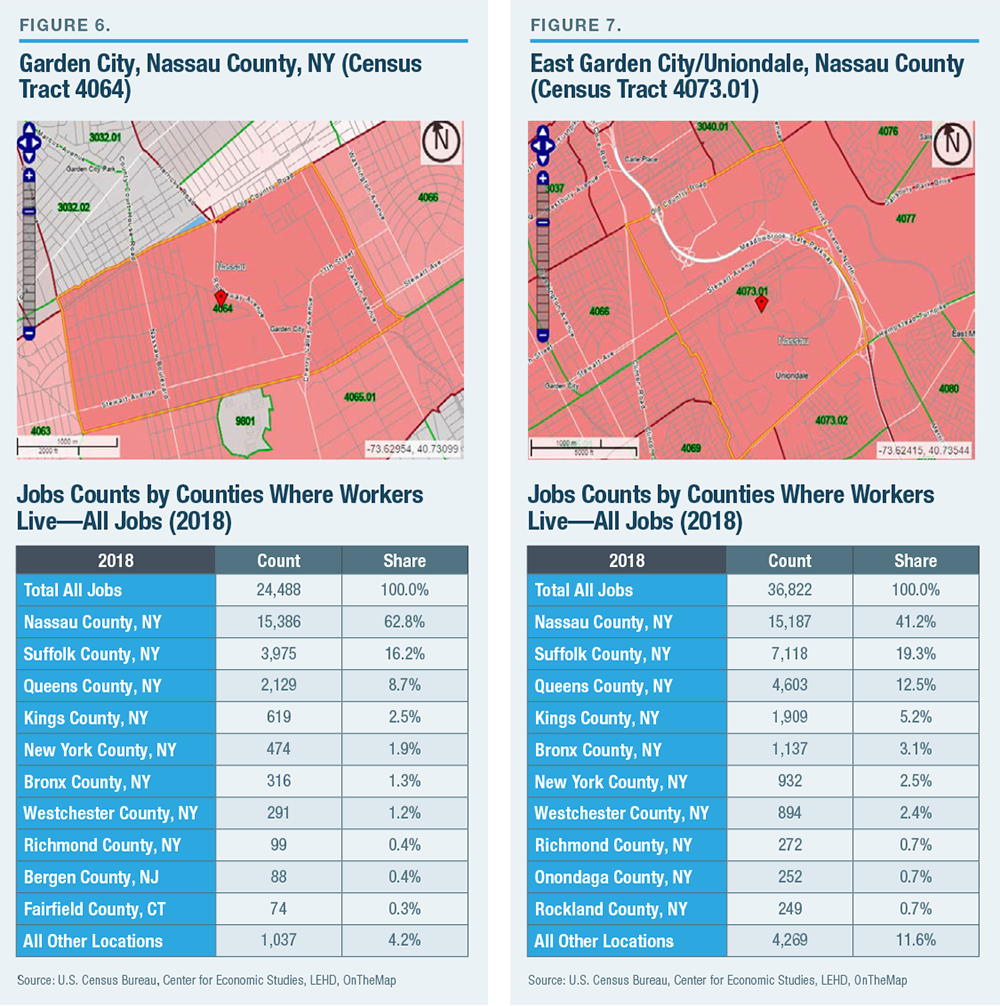

To lower high median rents in suburban counties, alleviate road congestion, and address environmental goals, more housing needs to be provided that is conveniently accessible to workplaces. Large employment concentrations are often not proximate to rail stations. Many are centered on hospital and college campuses, retail centers, and office parks that are spread horizontally over large tracts of land and designed today to be separated from housing and accessed by workers primarily by car. Even when employment concentrations are served by commuter rail, there are evident opportunities to build new multifamily housing that could be accessible to large numbers of jobs by walking, bicycling, or short bus rides. This can be illustrated by looking at the major job concentrations in the three suburban counties with the largest numbers of jobs.[9] The census tracts in Nassau County with the largest number of county resident workers (more than 15,000 each) in 2018 are in Manhasset (tract 3018), Garden City (tract 4064), and East Garden City/Uniondale (tract 4073.01, actually unincorporated areas of the Town of Hempstead). The Manhasset tract (Figure 5) had 42,393 total jobs in 2018. Nassau County accounts for 36.5% of workers’ residences, Queens for 22.8%, and Suffolk for 16.4%. Only 289 workers live within the tract itself, and no other individual census tract accounts for more workers. The workers likely live in widely scattered locations where they have been able to find housing that meets their needs and that they can afford. If there were more multifamily housing nearby, more workers could live near their workplace.

To lower high median rents in suburban counties, alleviate road congestion, and address environmental goals, more housing needs to be provided that is conveniently accessible to workplaces. Large employment concentrations are often not proximate to rail stations. Many are centered on hospital and college campuses, retail centers, and office parks that are spread horizontally over large tracts of land and designed today to be separated from housing and accessed by workers primarily by car. Even when employment concentrations are served by commuter rail, there are evident opportunities to build new multifamily housing that could be accessible to large numbers of jobs by walking, bicycling, or short bus rides. This can be illustrated by looking at the major job concentrations in the three suburban counties with the largest numbers of jobs.[9] The census tracts in Nassau County with the largest number of county resident workers (more than 15,000 each) in 2018 are in Manhasset (tract 3018), Garden City (tract 4064), and East Garden City/Uniondale (tract 4073.01, actually unincorporated areas of the Town of Hempstead). The Manhasset tract (Figure 5) had 42,393 total jobs in 2018. Nassau County accounts for 36.5% of workers’ residences, Queens for 22.8%, and Suffolk for 16.4%. Only 289 workers live within the tract itself, and no other individual census tract accounts for more workers. The workers likely live in widely scattered locations where they have been able to find housing that meets their needs and that they can afford. If there were more multifamily housing nearby, more workers could live near their workplace.

Tract 3018 includes the Manhasset Long Island Rail Road station, whose open parking lot indeed represents a transit-oriented development opportunity. However, the station is distant from the major employment center in the tract, North Shore Community Hospital, and associated professional office buildings on Community Drive. Commercial properties along Northern Boulevard—particularly a Macy’s department store with a vast open parking field—offer additional opportunities for multifamily housing developments that would be easily accessible to the job center.

New privately financed multifamily housing has been constructed nearby without direct public subsidies. The 191-unit Avalon Great Neck, on East Shore Road, just to the northwest, was completed in 2017 on a site formerly used for oil storage. In exchange for tax exemptions, the development includes 20 below-market-rent units.[10]

The Garden City tract (Figure 6) includes Nassau County government offices, and, of its 24,488 total jobs in 2018, a much higher percentage of workers, 62.8%, live in Nassau County. As in the case of Manhasset tract 3018, only a small fraction of workers—278, or 1.1%—live in the tract, and no tract accounts for a larger number of workers’ residences.

The Mineola Long Island Rail Road station, among the best-served in the county, is immediately adjacent to the census tract, allowing rail access not only to New York City but to large swaths of the county. Nonetheless, the tract includes and is adjacent to enormous expanses of open parking, associated with public buildings and private commercial properties. This land used for parking could provide tens of thousands of units of multifamily housing.

The village of Mineola, just to the north, has been more receptive to new apartment housing than Garden City—for example, the 192-unit Modera Metro Mineola opened in 2019.[11]

The East Garden City/Uniondale tract (Figure 7) had 36,822 total jobs in 2018; 41.2% of the workers lived in Nassau County, 19.3% in Suffolk, and 12.5% in Queens. Tract 4073.01 is largely nonresidential—but no Nassau census tract had more than 0.4% of its workers as residents. This tract includes the Roosevelt Field shopping mall, other retail and commercial properties, and Hofstra University. Like the other large job centers, the tract has little housing but enormous amounts of open parking where large amounts of multifamily housing could be developed. Additional sizable parking fields are found immediately adjacent. The tract does not have a commuter rail station, although the Carle Place station is just to the north.

Freeing parking lots for development is not an original idea. Nassau County has been trying for more than a decade to put together a viable proposal for the county-owned Nassau Coliseum site, which is in the East Garden City/Uniondale tract. The county cannot move forward, however, without the approval of the Town of Hempstead, which has jurisdiction over zoning.[12] The plan included 500 units of housing, all relatively large units that would probably rent or sell at high prices, although the developer is currently reconsidering this component.[13]

Freeing parking lots for development is not an original idea. Nassau County has been trying for more than a decade to put together a viable proposal for the county-owned Nassau Coliseum site, which is in the East Garden City/Uniondale tract. The county cannot move forward, however, without the approval of the Town of Hempstead, which has jurisdiction over zoning.[12] The plan included 500 units of housing, all relatively large units that would probably rent or sell at high prices, although the developer is currently reconsidering this component.[13]

The decades-long problem of housing locked out of job-rich areas is not limited to Nassau County. Suffolk’s median rent is nearly as high as Nassau’s. Its highest-employment census tract in 2018 was in Melville (tract 1122.06), straddling Route 110 and the Long Island Expressway. It is a collection of commercial buildings surrounded, again, by vast parking fields. Of the 45,409 workers in the tract in 2018, only 361 lived within it.

Westchester is qualitatively different from Nassau and Suffolk. It has the greatest percentage of resident workers—22.6%—commuting to Manhattan. Its own job centers are smaller and, in some cases, urban, surrounded by multifamily housing and well served by transit. Two of the three Westchester census tracts with the largest number of county resident workers are in downtown White Plains, a transit hub (census tract 93, with 17,992 jobs in 2018); and just north of downtown Yonkers (census tract 6, with 6,340 jobs), including a major hospital and also very transit-accessible. Large residential developments have been approved in downtown White Plains[14] and Yonkers,[15] and more are proposed.[16] These two cities are receptive to new housing proposals, and state intervention is not needed. Of the three large Westchester employment clusters, only Valhalla (census tract 9810), with 10,398 jobs, including Westchester Medical Center, is characterized by sprawling parking lots with little nearby housing, similar to job-rich areas in the Long Island suburbs.

Land-Use Regulation and Proposed Reforms in New York State

New York State delegates zoning and other land-use regulations to the lowest applicable level of government; outside of cities, it thus falls to incorporated villages and, for unincorporated land, towns.[17] This makes for a high degree of regulatory fragmentation. Nassau County, for example, comprises two cities, three towns, 64 incorporated villages, and more than 100 unincorporated areas.[18] While the counties have certain powers to review zoning approvals by towns and villages that affect county interests, such as roads or drainage systems, the county has no ability to force a local government to act in the countywide interest—for example, by allowing the construction of multifamily housing. The governmental fragmentation also means that the fiscal impacts of development are extremely localized. Again, looking at Nassau County, there are 54 school districts.[19] A large residential development could force a significant increase in school taxes in a small district, thus making its homes relatively less attractive to buyers.

Discretionary zoning actions in New York State are, however, subject to environmental review under the Environmental Conservation Law and the implementing regulations.[20] State regulations exempt the construction of single-, two-, or three-family homes from environmental review.[21] Regulations do require an environmental review of the construction of 50 or more housing units that will not be connected to an existing sewer system, as well as, in a community of 150,000 or fewer, the construction of 200 units if they are connected to a sewer system.[22] Public review agencies may determine the appropriate level of review for projects of an intermediate size.[23]

In his fiscal year 2022 executive budget, Governor Andrew Cuomo has proposed the Rail Advantaged Housing Act,[24] which is intended to address some of the impediments to new housing discussed in this report. The legislation would empower county legislatures to permit an expedited review of rezoning proposals that allow more housing in areas within a half-mile of Long Island Rail Road or Metro-North commuter rail stations in the county (the legislation would not apply in New York City). The zoning change itself would still be enacted by the applicable city, town, or village government. If the rezoning proposal was within review thresholds established by the Department of Environmental Conservation for the projected population increase and the projected decrease of commuter parking—and the applicant paid in to a “local agency zoning mitigation account” (an amount set by a specified formula) to “mitigate the impact of housing construction on the quality of a jurisdiction’s environment and on a local agency’s ability to provide essential public services”—the proposal would be deemed exempt from environmental review.

This proposal represents Cuomo’s first, rather modest, effort to expedite the construction of multifamily housing in appropriate suburban locations. The Rail Advantaged Housing Act continues to respect local control of zoning while providing the possibility of a financial incentive for local governments to be more receptive to rezoning. Private developers are encouraged to apply for zoning changes by being exempted from costly environmental reviews. The formulaic payments into a “local agency zoning mitigation account” would provide predictability as to the costs of securing zoning approvals. New York local governments do not currently have clear authority to impose “impact fees” on new development to offset the added infrastructure or costs that such developments may impose.[25]

At about the same time as Cuomo’s budget proposals were released in January 2021, legislation was introduced in the state assembly and senate to clear the way for accessory dwelling units throughout the state. According to a press release by a coalition of advocacy groups:

The proposed legislation[27] aggressively asserts the state’s interest in allowing ADUs, overriding a range of local zoning and other regulatory requirements that might be used to impede the construction of these dwellings. However, it also undercuts this aggressive stance by imposing “good cause eviction” requirements, which make terminating a tenancy at the end of a lease term difficult and subject to costly and uncertain proceedings in court. Additionally, rent increases are capped without any provision for recovery of capital improvements. These requirements are a strong disincentive for any homeowner to take advantage of the law.

By prioritizing the continuity of tenancies in housing units that do not currently exist over providing homeowner- investors with a reasonable expectation of an economic return, the legislation undercuts its presumed goal of producing ADU housing at scale. The legislation is not entirely ineffective as drafted: homeowners will still be motivated to create ADUs for relatives or household employees. However, the larger potential of ADUs as profit-making investments for homeowners would not be realized.

Overcoming Local Governments’ Unwillingness to Allow New Housing

A recent report by Noah Kazis for the NYU Furman Center provides a broad overview of how other states have set new ground rules for zoning.[28] These rules are intended to ensure that local zoning addresses the statewide concern in providing the population with decent and affordable housing in proximity to workplaces and not just the local interest in maximizing property values while minimizing public services for those who are not fully able to pay for them. Kazis notes:

“The fiscal and political incentives for restrictive zoning are difficult for any local government to avoid,” Kazis adds. “Thus, while there are some suburban jurisdictions in New York that are intentionally and invidiously exclusionary, even the most well-meaning towns will be prone to low-density, exclusionary zoning.”[30]

Kazis summarizes the major types of state approaches to zoning reform. One is to require local governments to allow ADUs. In California, local governments must not only allow ADUs but are prohibited from enacting other types of restrictions, such as parking requirements, minimum lot sizes, or impact fees, that effectively prevent these units from being constructed.[31] As New York’s ADU legislation takes form, advocates and legislators should be alert as to how such provisions, if allowed, can nullify the intent.

Partial preemption of local zoning—in which state law specified that local governments cannot go beyond certain limits in restricting new housing—is increasingly prevalent. In January 2021, Massachusetts enacted new legislation (H.5250) requiring, as described by Salim Furth of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, that

The minimum required density in the multifamily district is set at 15 units per acre or more. Noncompliant communities could be denied certain types of state infrastructure funding. Furth finds that at least 115 of the 175 affected cities and towns will require a rezoning to come into compliance with the law.

An additional legislative approach that seems relevant to New York State’s specific conditions is the institution of an appeals process for local zoning determinations, or “builder’s remedy.” In Massachusetts, Kazis writes, the state law known as “40B”

Massachusetts’s 40B law, according to Kazis, results in far more use of federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits in subsidized affordable housing, in comparison with the New York suburbs. The leverage of a threatened appeal helps developers obtain initial approvals for mixed-income housing from the locality.

The orientation of the builder’s remedy to mixed-income housing may be important in building political support in left-leaning state legislatures. Moreover, private developers will accept reasonable affordability targets for a portion of the units in exchange for tax exemptions, as in the Avalon Great Neck development discussed above. In any case, allowing developers to appeal to a higher, more receptive, level of government localities’ decisions to turn down, or attach unduly restrictive conditions to proposals for, new multifamily housing makes sense even if the housing does not have a regulated mix of incomes. Multifamily housing is inherently more affordable than single-family detached homes in the same community, and the more of it there is, the more likely that even unregulated rents will be affordable to a broader range of incomes than can access such housing today. This benefit in itself should justify enacting a builder’s remedy.

Conclusions and Recommendations

With the legislation proposed in Albany, along with laws already enacted in other states, New Yorkers have much to work with for reforming exclusionary zoning practices in the suburbs. Cuomo’s Rail Advantaged Housing Act, for example, could be more effective in facilitating new housing if it were broadened to a “Transit Advantaged Housing Act” that is not exclusively targeted to areas near rail stations. An expanded law would:

- Target all communities and unincorporated areas in the seven counties of the New York Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District, outside New York City.

- Require, as in Massachusetts’s H.5250 law, all communities and unincorporated areas to have a reasonably sized zoning district where multifamily housing is permitted as-of-right; and if the community has a commuter rail station, the multifamily district should be located within a half-mile of it. If the community does not have a commuter rail station, the district should be located within a half-mile of arterial roads (state numbered roads and other roads managed by the county) where bus service is, or could be, provided, or within a half-mile of a concentration of employment, if one exists within, or adjacent to, the community. Communities that fail to comply would become ineligible for state aid.

- Provide an expedited review process and a “local agency zoning mitigation account” to be paid by new developments, similar to the provision in Cuomo’s proposed Rail Advantaged Housing Act; this measure would reduce costs for local governments when enacting zoning changes and ensure that funds are available to cover added infrastructure and service costs.

- Provide an appeals process to the county planning commission for multifamily developments that exceed the as-of-right density, similar to the Massachusetts 40B process but potentially broader in scope and not limited to mixed-income developments. The existence of such an appeals process will encourage applications to local governments and give developers negotiating leverage.

The definition of a reasonably sized zoning district is important, since local governments can undercut its intent by limiting a zoning district to land developed with already-existing housing. At a minimum, the district should include commercially developed land within the community or unincorporated area. Suburban communities arguably have an interest in preserving the character of residential communities, but this should not apply to commercial land, much of which is open parking. Even many of the buildings and structures within commercial areas are likely to be repurposed or redeveloped in coming years as the long-term effects of the pandemic-induced recession play out.

Among these effects are likely to be reduced demand for retail and office space in suburban office parks. In February 2021, for example, the Town Board of Yorktown Heights in northern Westchester County was considering the redevelopment of a former retail site with 150 multifamily units and new retail.[34] The community does not have a railroad station, but the site is adjacent to a state-numbered highway. Nearby bus service is provided to White Plains and the Croton railroad station. The proposed Yorktown Heights development represents the type of development that should be as-of-right in a designated area of every New York City suburban community.

Also, a version of the proposed state ADU legislation could be beneficial to the New York City suburban counties. Like the current proposal, the legislation should allow ADUs broadly on any lot, not only those currently limited to single-family homes. ADU legislation would be more effective as a housing-production measure if it avoids conditions, such as rent caps and restrictions on the landlord’s ability to select a new tenant upon the expiration of the lease, that deter homeowners from creating these units. Allowing ADUs won’t solve the suburban housing problem alone. It will provide a useful complement to broader transit-oriented development legislation, particularly by permitting housing for homeowners’ relatives or other acquaintances and enabling homeowners to supplement their incomes.

The combination of these two laws would be a revolution in New York State land-use policy and would make a major contribution to relieving the region’s perpetual housing shortage. Combined with more sensible housing policies in New York City,[35] these initiatives accommodate growth in the regional labor force and facilitate economic expansion in a state that depends on the prosperity of the New York City region for its fiscal health. Failure to act, as has been the default tendency of past legislatures, means the continuation of a housing crisis, favors only affluent homeowners in the suburbs, and places economic recovery further out of reach.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).