Midwest Success Stories: These 10 Cities Are Blooming, Not Rusting

America has many cities that are booming and others that are in severe distress. These two groups get the most public attention.

But what about cities between those two extremes—cities that are doing above average economically and demographically but not yet at the superstar level? This paper focuses on 10 such cities in the greater Midwest.

While the “Rust Belt” accounts for the lion’s share of America’s highly distressed cities, the image that this entire region is uniformly failing is not the whole story. There are well-performing cities in the Midwest that are growing in population and jobs faster than the U.S. average and have high-value economic sectors, civic assets, and amenities. They could potentially raise their performance to be more comparable with Sunbelt boomtowns.

These cities have succeeded by becoming economic centers of their state or immediate region. But to get to the next level, their challenge is to expand their appeal beyond their backyard to the nation at large. Moreover, if they fail to do this, their robust performance may degrade in the future as the population of their hinterlands declines.

While burdened with some factors beyond their control, such as cold winters, the cities in America’s older industrial heartland that have significantly reinvented themselves can find a way to grow, especially if they avoid repeating the housing-policy mistakes of coastal cities.

On the Threshold of the Major Leagues

Let us define cities as “superstars” if their metro areas exhibit real GDP per capita greater than 120% of the national average and per-capita income greater than 130% of the national average.[1] Another class of cities may be called “boomtowns”—growing both population and jobs at 1.5 times the national average.[2] Profiling urban America this way shows approximately 60 cities at the top of the performance spectrum.

At the low-performing end are about 50 deeply challenged urban regions[3] that I have characterized as “stagnating.”[4] These cities are in metro areas of fewer than 1 million people with a central city that has lost 20% of population or more from its peak. The best- and worst-performing metro areas total a bit more than a quarter of all U.S. metro areas.

What about the large number of cities in the middle? They are very diverse and cannot be lumped together in a single group. There is, however, a subgroup of cities, located in the Midwest, that perform above the U.S. average on metrics including population growth, job growth, GDP per capita, and college-degree attainment. To use a baseball metaphor, these cities are successful AAA players looking for a way to move up to the major leagues.

They are:

- Cincinnati, Ohio

- Columbus, Ohio

- Des Moines, Iowa

- Fargo, North Dakota

- Grand Rapids, Michigan

- Indianapolis, Indiana

- Kansas City, Missouri-Kansas

- Lexington, Kentucky

- Madison, Wisconsin

- Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minnesota

The metropolitan areas where these cities are located are all in the Midwest or Great Plains states, with the exception of Lexington, Kentucky. While Kentucky is usually included in the South, its slower-growth economic profile has resembled more the Midwest than states such as North Carolina or Texas.

Economic Indicators

All the metro areas except Cincinnati are growing in population at a rate exceeding the national average (Figure 1). The five fastest are growing at a rate greater than 1.5 times the national average. This is particularly noteworthy in a region of the country better known for shrinking cities.

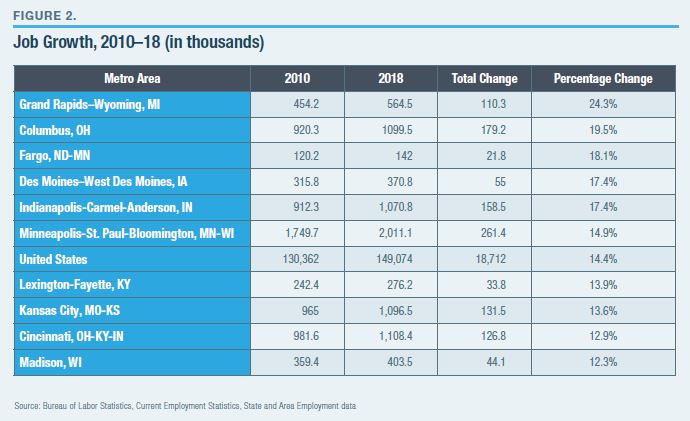

These metro areas have also experienced solid job growth since 2010 (Figure 2), six of them faster than the national average and the others only marginally lower. All but two of these regions have a per-capita GDP (Figure 3) that exceeds the national average.

These metro areas have also experienced solid job growth since 2010 (Figure 2), six of them faster than the national average and the others only marginally lower. All but two of these regions have a per-capita GDP (Figure 3) that exceeds the national average.

High-skill labor is increasingly important to regional economic success, and one measure of this is the educational level of the population. All 10 metro areas have college-degree attainment rates—the percentage of adults over age 25 with a B.A. or higher—that exceed the national average (Figure 4). Madison and Minneapolis–St. Paul have college-degree attainment above 40%.

High-skill labor is increasingly important to regional economic success, and one measure of this is the educational level of the population. All 10 metro areas have college-degree attainment rates—the percentage of adults over age 25 with a B.A. or higher—that exceed the national average (Figure 4). Madison and Minneapolis–St. Paul have college-degree attainment above 40%.

These cities are not coastal superstar cities or Sunbelt boomtowns. Nevertheless, their solid demographic and economic statistics are at odds with common perceptions of this region of the country.

These cities are not coastal superstar cities or Sunbelt boomtowns. Nevertheless, their solid demographic and economic statistics are at odds with common perceptions of this region of the country.

Civic Assets

The 10 high-performing cities in the greater Midwest poised to reach the next level share certain advantages: they are relatively large; some of them are state capitals; they have airports; and some of them are home to their state’s flagship university (Figure 5).

These cities have other economic and cultural assets as well. Cincinnati and Minneapolis–St. Paul are noted for their large number of blue-chip corporate headquarters, such as P&G and Kroger in Cincinnati, and 3M and Target in Minneapolis. Madison, nationally known for a high quality of life, is home to tech company Epic Systems, with 9,000 employees. Columbus and Indianapolis were finalists in Amazon’s HQ competition, reflecting their strong regional tech ecosystems that have driven billion-dollar exits like ExactTarget in Indianapolis and CoverMyMeds in Columbus. The annual ArtPrize competition in Grand Rapids draws huge crowds and national press. Lexington’s horse country is internationally renowned.

These cities have other economic and cultural assets as well. Cincinnati and Minneapolis–St. Paul are noted for their large number of blue-chip corporate headquarters, such as P&G and Kroger in Cincinnati, and 3M and Target in Minneapolis. Madison, nationally known for a high quality of life, is home to tech company Epic Systems, with 9,000 employees. Columbus and Indianapolis were finalists in Amazon’s HQ competition, reflecting their strong regional tech ecosystems that have driven billion-dollar exits like ExactTarget in Indianapolis and CoverMyMeds in Columbus. The annual ArtPrize competition in Grand Rapids draws huge crowds and national press. Lexington’s horse country is internationally renowned.

The Challenge Ahead

While these cities have established themselves as hubs for their state or region, migration statistics show that they overwhelmingly attract people from within their own state (or immediate region) and have a very limited draw from the rest of the country. Sunbelt boomtowns, by contrast, predominantly draw migrants from out of state.

The Internal Revenue Service provides annual estimates of migration between counties (and states) based on tax-return data. The data exclude non-filers but cover a very large universe of people—more than 100 million tax returns.[5] The IRS county-to-coun-ty data also allow for annual time series comparisons (with some caveats) back to 1990.

These data can be aggregated to the metropolitan statistical area (MSA) level to track migrations to and from MSAs by county, MSA, or state. Various flows for in, out, net, or gross migration can also be produced.

“In-state” vs. “out-of-state” from a metro migration perspective is complicated by the fact that many MSAs straddle state boundaries. For example, the Kansas City metro area spans Missouri and Kansas. Unlike counties or cities, metro areas are not subsidiary entities within states. To thus demonstrate the different character of migration flows between high-performing midwestern cities and Sunbelt boomtowns, Figure 6 compares migration levels into and out of three midwestern MSAs with three Sunbelt MSAs in recent years.

In Figure 6, “in-state” migration is net flows to an MSA from counties within the state that are not part of the MSA itself. For example, between 2009–10 and 2015–16, Columbus experienced a net increase of 24,895 individuals from Ohio (i.e., more people from Ohio moved to Columbus than moved out of Columbus to elsewhere in Ohio) and a net outflow of 11,718 to the rest of the U.S. (i.e., more people moved out of Columbus to other states than moved into Columbus from other states). A similar inflow/outflow migration pattern was true for Indianapolis. Des Moines had a small positive net inflow of people from outside Iowa.

In Figure 6, “in-state” migration is net flows to an MSA from counties within the state that are not part of the MSA itself. For example, between 2009–10 and 2015–16, Columbus experienced a net increase of 24,895 individuals from Ohio (i.e., more people from Ohio moved to Columbus than moved out of Columbus to elsewhere in Ohio) and a net outflow of 11,718 to the rest of the U.S. (i.e., more people moved out of Columbus to other states than moved into Columbus from other states). A similar inflow/outflow migration pattern was true for Indianapolis. Des Moines had a small positive net inflow of people from outside Iowa.

By contrast, Austin, Nashville, and Raleigh drew large numbers of migrants from out of state—more than from within their own states. It’s notable that Nashville and Raleigh draw a comparatively limited number of migrants from within their own states—fewer than any of the midwestern metro areas. The Sunbelt boomtowns have a national migration draw while the 10 midwestern cities have only an in-state draw.

While this analysis focused on three of this report’s 10 metropolitan areas, similar results hold for the others. They all draw net migrants almost exclusively from the state or states in which the metro area is contained. In limited cases, they also draw significant numbers from another nearby state. For example, Minneapolis–St. Paul enjoys a strong net inflow of residents from South Dakota, and Lexington has a stronger draw from Ohio than it does from Kentucky. But they lose migrants on a net basis to the remainder of the country (Figure 7).

In short, the 10 high-performing cities generate growth in part by attracting migrants from within their own states. This helps lifts them above other places in the regions that are losing people to them. Conversely, their lack of a national draw helps explain why their growth rates trail those of the Sunbelt boomtowns.

In short, the 10 high-performing cities generate growth in part by attracting migrants from within their own states. This helps lifts them above other places in the regions that are losing people to them. Conversely, their lack of a national draw helps explain why their growth rates trail those of the Sunbelt boomtowns.

The Implication of Migration Patterns

The draw of migrants from in-state or nearby to prospering cities and their metro areas is normal. But the dependence of the next-level cities on in-state migrants represents a challenge for their future. The states that these 10 cities are drawing from are demographically weak, with many areas shrinking in population. This suggests that the flow of in-state migrants cannot be sustained indefinitely. And this means that existing businesses and potential new businesses cannot be confident of a labor supply, especially of the talented and their families. If these cities are to reach the next level or maintain their current situation, they will have to expand their appeal.

While it can be difficult to determine the true reason a business chooses one location over another, anecdotes suggest that migration patterns matter. Amazon selected Nashville for a 5,000-employee operations headquarters. Nashville is smaller than Columbus or Indianapolis and is not known as a center of the technology industry. However, it does have a large flow of inbound migrants from around the nation. And it is easy to recruit people to move to Nashville from almost anywhere.

By contrast, recruiting prospects to midwestern cities who did not grow up there, marry someone who grew up there, or go to school there can be difficult. The saying in Minneapolis is: “It’s really hard to get people to move to Minneapolis, and it’s impossible to get them to leave.”[6] Other next-level cities have similar experiences. They face a difficult initial recruitment challenge but are stronger in retention, in many cases.

In any case, the lack of a significant net inbound talent flow makes these cities more dependent on their local labor markets for supplying talent to businesses, which inhibits efforts to attract highvalue employers that intend to recruit nationally.

Figure 8 shows population growth rates for the states in which these metro areas are contained. All but North Dakota are growing slower than the national average rate. The cities profiled in this paper are in states that are overall demographically weak, especially outside these metro areas. Many counties in them are experiencing absolute population decline (Figure 9). The current population and economic growth rates of these metro areas will not likely be sustainable if they have to rely on hinterlands with declining populations.

Broadening Urban Appeal

Broadening Urban Appeal

If they are to reach the next level of economic performance, the cities profiled in this paper (and others like them elsewhere in the country) need to attract migrants—international as well as domestic—from outside their home regions. In many respects, the 10 cities in this paper (and others with similar profiles) already have the growing economies and amenities necessary to compete with Sunbelt boomtowns. They all have high-quality restaurants and (the by-now virtually obligatory) microbreweries and local coffee roasters. Some also have art museums, symphony orchestras, and other cultural assets that exceed the quality of those in the Sunbelt.

Nevertheless, one major factor standing in the way of in-migration is the weather. Economist Edward Glaeser has noted the link between average January temperature and population growth since 1960.[7] All the cities featured in this report experience the full four seasons, including genuine winter. Some, like Fargo and Minneapolis, are famous for extreme cold.

Cold weather is not, however, a fatal handicap. Three of the top 20 fastest-growing metro areas in the U.S. between 2017 and 2018 were in Idaho: Boise, Coeur d’Alene, and Idaho Falls. Since the 2009–10 period, Boise has drawn nearly twice as many people from California as it has from Idaho itself. It has also attracted a significant number of people from Arizona. Boise’s average January high is 39 degrees, with an average low of 22, only slightly better than some of the 10 midwestern cities. Similar conditions prevail in Coeur

d’Alene, which also has a strong California draw.[8] Idaho’s topography may be judged superior to that of the Midwest; but until recently, the state and its communities did not enjoy an especially high reputation. The stereotype of Idaho in the public mind was of potatoes and survivalist compounds (e.g., Ruby Ridge).

Create a Welcoming Environment for Newcomers

While midwestern cities can’t change the weather, they can focus on what is actionable. The first key step is to create a welcoming environment for outsiders. If outsiders cannot get access to social and professional networks in a new city or are viewed as second-class citizens, it’s unlikely that that city will become a choice destination for migrants. To be sure, many of the midwestern cities in this paper are already welcoming. Even so, barriers can be lowered. In some cases, this may be simple. For example, new residents to Indianapolis (and elsewhere in the state) once had to pass a written exam to obtain an Indiana driver’s license. That requirement was dropped earlier this year. A more substantive “to do” is facilitating the easy transfer of other out-of-state credentials such as occupational licenses.

Other barriers are not so simple. For example, Minneapolis is known for its “Minnesota nice” affect, which is friendly but keeps outsiders at a distance socially. Some locals have suggested that “ ‘Minnesota nice’ could become a serious economic problem for the Twin Cities,” especially when it comes to attracting minority residents.[9] Local sayings include “Minnesotans will give you directions to everywhere but their house” and “You want to make friends in Minnesota? Go to kindergarten.”[10] A similar case prevails in Cincinnati, a city where, famously, the first question people ask upon meeting someone is, “Where did you go to high school?”

Additionally, these cities need to make significant improvements in their “brand” and the public narrative around their city.[11] Cities eager to grow need an aspirational narrative of life in their city that people without a historical connection can imagine themselves being a part of. Limitations or current flaws (e.g., winter) can be straightforwardly acknowledged without excessive negativity. And cities should take care to avoid undertaking initiatives that could be viewed as a sign of desperation. Financial incentives to new residents, such as those offered by the state of Vermont[12] and the city of Tulsa,[13] are an example of what to avoid.

Every city has a convention and visitors’ bureau chartered to attract tourists. The Greater Columbus Convention & Visitors Bureau has an annual budget of over $14 million.[14] But few cities anywhere have an organization dedicated to attracting new permanent residents who have no historical connection to the community. This is a critical missing element in these cities’ economic development efforts.

High-performing cities that want to get to the next level need to establish an organization devoted to attracting out-of-state, out-of-region talent. Funding will likely need to come primarily from the business community or existing funders of economic development. Such an organization can be part of the greater umbrella of economic development organizations, potentially sharing services with them. Unless it is someone’s dedicated job to attract these new residents, progress on this front is unlikely to be made.

Implement the Right Housing Policies

The cities profiled in this report are all very affordable—a key asset. They offer solid economies and a high level of urban amenities at a much lower cost than coastal cities—and even less than some Sunbelt boomtowns such as Austin, where housing prices are increasing.

The danger is that, as these midwestern cities continue to grow, they will repeat the mistakes of the coastal cities: urban containment,[15] rent control, inclusionary zoning,[16] and so on. These and other policies are contributors to coastal unaffordability. They are also all heavily promoted by urbanists based on both coasts.

These high-performing cities should look to permit somewhat increased density in zones adjacent to the urban center. This means allowing denser and mixeduse housing—such as apartments with ground for retail—in more places than are currently permitted.

This does not require eliminating all single-family zoning, as Minneapolis has done.[17] But at a minimum, targeted up-zoning to allow densification in select areas will help to moderate prices. And cities should avoid the kinds of rezonings being evaluated by Des Moines, which is planning to make the construction of low-cost single-family homes difficult by increasing minimum sizes and other similar changes.[18]

Conclusion

Many cities in America are performing well economically and demographically, even if not at the level of coastal superstars or Sunbelt boomtowns. A number of them are even in the greater Midwest, belying the stereotype of a failed region. These midwestern cities have high-value assets and performance levels that are, in some cases, just below those of Sunbelt boomtowns.

However, these cities have been almost entirely dependent on in-migration from their home state or immediate region to fuel their growth. They are not national destinations for talent. This lack of a national draw poses a risk to their future.

Because of their cold winters, these cities may always operate at a disadvantage in attracting migrants. Nevertheless, they can seek to become more competitive. To do so, they can:

- Eliminate legal and social barriers to entry for newcomers in order to make the city welcoming and socially and economically open.

- Create a dedicated economic development organization whose mission is attracting new residents with no historical ties to the state.

- Focus on changing the city’s national perception (brand) through improved marketing.

- Implement housing policies that keep prices affordable and allow for the development of additional urban-style areas in line with demand.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).