Most people who care about American public life would admit that our political rhetoric is in a bad way. We seem to no longer understand the role veracity should play in the public sphere.

Donald Trump, for one, seems to have had a preternatural gift for mendacity during his time in the White House. At times, major media outlets seem more interested in advancing narratives that comport with their politics than in sticking to the facts, while some minor outlets spread patently false news stories with abandon. Fringe groups on both the far left and the far right traffic in conspiracy theories. Some "fact checkers" critique obviously satirical material, while others "correct" facts they find inconvenient.

Part of our problem is encapsulated by the now famous phrase "seriously, not literally." Journalist Salena Zito offered this approach to understanding some of President Trump's musings, suggesting he often conveys meaning without getting precious about precision. He's making a point, the argument goes, and the literal truth of the matter is subordinate to the overarching story — a story that may have some underlying truth to it.

"Seriously, not literally" rests on the idea that there exists a difference between fact and gist — that we can advance the latter without obsessing about the former. You needn't be a Cassandra to think this invites confusion, even deception — it does. In fact, the distinction between the two, and the disorientation that results, are now visible across our politics. Do we look past the factual inaccuracies in the 1619 Project and just take seriously its overarching point about centuries of American racism? Do we ignore the false claims undergirding the Trump campaign's election lawsuits and just take seriously their primary claim that institutional forces sought to undermine his presidency? Do we discount the lack of evidence for an accusation of sexual assault and simply take seriously the underlying point about sexism, abuse, and privilege? Do we move past questionable arguments in a study on global warming or welfare dependency and take seriously their main theses on climate change or personal responsibility?

It is instructive that, in an unguarded moment, advocates of any of these stories might admit that not every claim involved has been verified. But they might also quickly pivot to defending the general thrust of the argument. In fact, were one to question the veracity of any particular claim in the story, that person might be charged with denying the seriousness of racial discrimination, biased news coverage, climate change, or other political shibboleths.

One response could be to declare gist without literal accuracy off-limits in the public square and demand society develop strong norms that deem out-of-bounds anything apart from precise truth. Accordingly, we'd conclude that meaning must always be transmitted via transparent, literally veracious language.

But that can't be. If it were, we would have to ban people from using innocuous phrases like "America is a city on a hill," "that's a Trojan horse," "the most dangerous place is between him and a camera," and "that's a great plan (dramatic eye roll)." In each instance, even though the literal meaning of the statement is unquestionably untrue, important information is conveyed nonetheless.

We thus find ourselves in a pickle. We must be able to trust the information presented to us — it would cost us dearly were we to make our decisions about voting, investments, or medication based on false information. But we also know that humans have developed useful ways of transmitting meaning outside of literalism. So what are we to do?

To sort through the dilemma, we should rely on three principles. The first is that political actors can share legitimate, valuable content without relying solely on literal statements. A great deal of meaning, after all, would be lost if officials were restricted to communicating like robots programmed to be curt and precise. In short, "take it seriously, not literally" turns out to be a valid defense of some forms of communication after all.

The second principle is that the question of whether a statement is legitimate despite its lack of literal truth depends on whether the speaker intends to deceive and whether the audience will be misled. If all involved understand that the words used are untrue if understood literally but that they are being used to accomplish something else, the benefits can outweigh the costs. A fiscal hawk discussing a bloated budget, for instance, doesn't actually want the public to believe his goal is to cut fat from government spending. His phrasing conveys significant meaning to those who understand the reference, and no real damage is done if a citizen mistakenly believes the policymaker is being literal.

Third, given that it is impossible to know for certain how listeners will interpret content, and that the costs of spreading false information can be sky-high, we must recognize that some institutions have a special duty to their audiences. The public must see certain institutions — and these institutions must see themselves — as authoritative. Thus, these bodies have obligations that provocative writers and protesters do not, and as a result, they must err on the side of veracity in their communication.

TRUTH AND MEANING

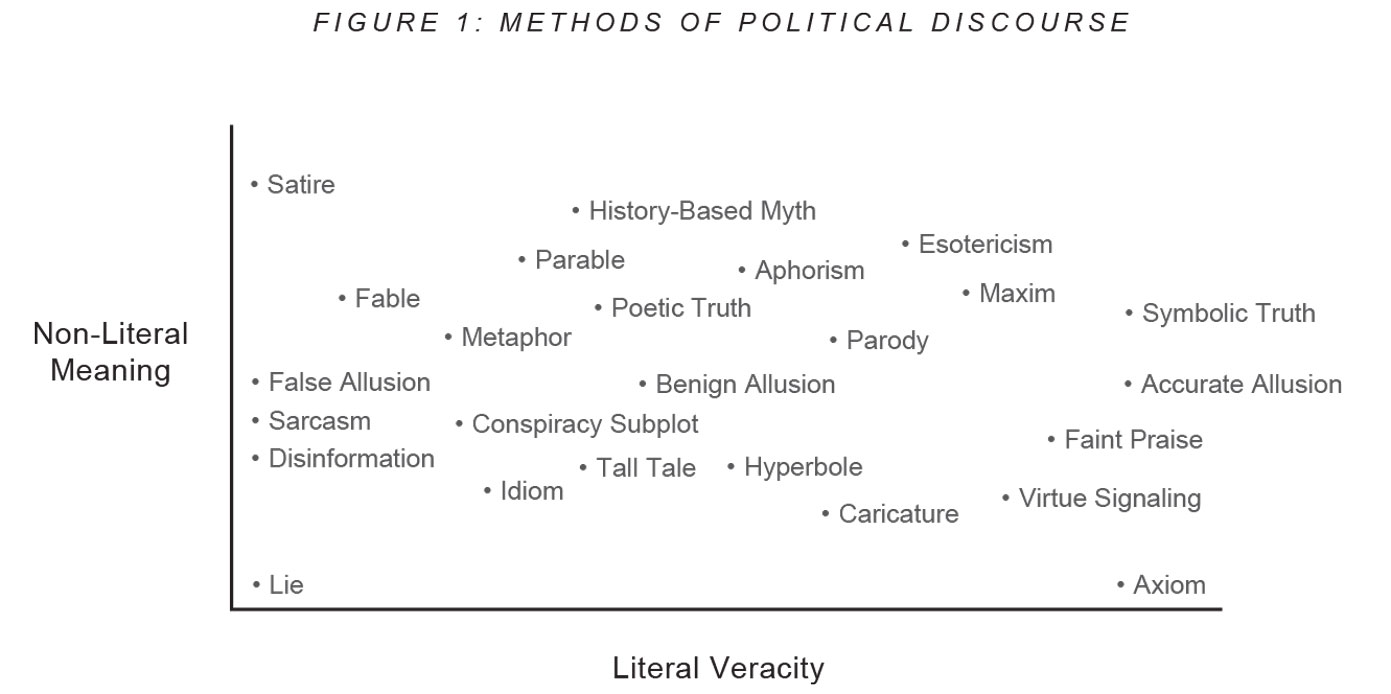

When assessing the legitimacy of a statement, it is not enough to consider its literal truthfulness alone. We should not imagine a spectrum with absolute truth (complete conformity with fact or reality) on the far right, absolute untruth on the far left, and then declare that the further right a statement appears on the spectrum, the better. We may be able to assess veracity that way, but we cannot account for the totality or legitimacy of the content. To do that, we would need to add a second dimension: meaning conveyed outside of literalism. This would allow us to assess the statement's level of veracity on an X-axis and the extent to which its meaning cannot be understood by a mechanical, literal interpretation on a Y-axis (see Figure 1).

In some instances, such as a straightforward axiom, the statement is literally true, and one can gather the entire meaning by following the words' precise definitions. The statement "one plus one is two," for example, is literally true, and the words themselves do not imply any additional message. Similarly, there are straightforward lies — false statements with no additional content. "One plus one is three" is a paradigmatic example. Because both statements operate solely on a literal level, they have no Y value, but their truth values directly oppose one another. The first statement — the one that is literally true — sits on the far right of the X-axis, while the second — which is literally false — sits on the far left.

And yet someone could say "two plus two is five" — a literal falsehood — and still convey some meaning. How can this be? If the statement is meant as a reference to George Orwell's 1984, then although it has no literal veracity (and thus no X value), it conveys meaning about authoritarian power and free will. In other words, it has some Y value.

Such "false allusions" are statements that are untrue if taken literally but nevertheless convey valuable content because they evoke meaning from another source. In public discourse, "et tu, Brute?" suggests disloyalty, "he's tilting at windmills" means fighting imaginary opponents, and "he's a Cassandra" — which I use above — means constantly foreseeing danger. They have meaning not because a windmill or someone named Brutus or Cassandra is involved, but because they pull meaning from Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Aeschylus, respectively.

Figure 1 shows the coordinates of false allusions and other literary devices as they would appear on the X- and Y-axes described above. The precise coordinates of each device here and in the following two figures are up for debate; the primary purpose of their estimated locations is to show how each can be assessed on different dimensions and how they compare to one another on these dimensions.

We can think of a variety of statements in our political discourse that appear on the far left (meaning they have meager literal truth) but have a range of vertical values. On the bottom left are untruths meant solely to deceive — the Eisenhower administration's 1960 denial that a U-2 spy plane had been shot down over the Soviet Union, for instance, or President Bill Clinton's televised lies about his affair with Monica Lewinsky. Leaders in these cases wanted the public to believe something that was not true, so their statements had no Y value. Slightly higher up the Y-axis would be a lie that's part of a disinformation campaign. While the statement is meant to deceive on its face, it carries greater meaning — its intent is to convey an underlying falsehood while also sowing general distrust of a person or institution.

When someone wants to call special attention to some matter at hand, he may use sarcasm — a type of verbal irony in which a person says the exact opposite of what he believes. After he squeaked by in the primaries during his second race for the U.S. Senate, Lyndon Johnson was derisively referred to as "Landslide Lyndon." Satire — sarcasm's more sophisticated cousin — is a patently untrue argument or story designed to make a broader point. Jonathan Swift's "A Modest Proposal," which suggested that impoverished Irish families might lessen their economic woes by selling their children as food to the rich, was an extended use of irony designed to shine the spotlight on elite cruelty toward the poor. In more recent years, the Babylon Bee has taken to poking fun at progressives and the Christian right in a similarly satirical fashion.

Literal untruth can also be used to draw an illuminating comparison via metaphor. In 1946, as the Soviet Union consolidated power in Eastern Europe, Winston Churchill declared, "an iron curtain has descended across the Continent." Similarly, President Clinton resolved in 1996 to "build a bridge to the 21st century," Martin Luther King, Jr., referred to the Declaration of Independence as "a promissory note," and commentators have called Ted Kennedy the "Lion of the Senate" and George Washington the "American Cincinnatus." Parables (often religious) and fables (typically featuring animals as characters) are fictive stories intended to convey moral lessons. The parables of the "Good Samaritan" and the "Prodigal Son" teach us about personal and civic virtue, Orwell's Animal Farm elucidates aspects of the Russian Revolution, and Aesop's lesson of "crying wolf" reels in alarmists. Justice Antonin Scalia's dissent in the independent counsel case Morrison v. Olson famously features the phrase "this wolf comes as a wolf" — a play on the "wolf in sheep's clothing" concept rooted in both Aesop's fables and the Bible.

Obviously, Johnson didn't win his 1948 primary in a landslide, Swift didn't want people to sell children as food, Washington wasn't an ancient Roman farmer, a pig didn't consolidate post-revolutionary power on a farm, a boy likely never played such tricks on villagers, and Congress didn't authorize a wolf to serve as an investigator. But valuable meaning is conveyed through these statements and stories even though each would be summarily rejected on literal grounds.

Things become even more interesting as we move rightward. Several means of political discourse have a bit more truth to them than metaphors and fables but also convey additional meaning, including history-based myths and tall tales. Some elements of these stories are typically true; there probably was a Trojan War, a King Arthur, and a giant lumberjack on the frontier, for example. We shouldn't believe various gods intervened on the side of Troy or Greece, or that there was a magical sword or a blue ox. And we should recognize that half the truth can be a great lie. But we should also appreciate that these stories have survived for so long because they tell us something about their times and about the human condition more generally.

There are also common expressions that are broadly understood even though a literal translation might render them unintelligible. Idioms like "it's raining cats and dogs" are meaningful not due to their literal definitions, but to their usage over time. We would understand what was meant if a legislator facing a major vote "beat around the bush" (avoided the subject), "bit the bullet" (did something difficult), or found himself — as I state above — "in a pickle" (in a tough position). Aphorisms are another literary device that provide insight or general truth through a pithy, memorable expression. One can always quibble about an aphorism's literal accuracy, but "if it ain't broke, don't fix it" tells us something about the dangers of tinkering, "you can lead a horse to water, but you can't make it drink" instructs us about the limits of advocacy, and "an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure" teaches us about foresight and early action.

There are also what we might call "benign allusions." Whereas a false allusion is untrue on its face and is only redeemed if the reader understands the reference, a reader who misses the reference of a benign allusion would simply breeze past it. For instance, the first sentence of this essay nearly replicates the first sentence of Orwell's "Politics and the English Language." Similarly, the clause about "half the truth" I use two paragraphs above comes from Benjamin Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanack. A reader who misses these allusions isn't misled, but given that Orwell's essay is about how debased political language can obscure meaning and Franklin's demonstrates how the witty or folksy use of words can illuminate greater meaning — two major themes of this essay — these allusions can be valuable if caught.

To draw attention to particular features of an object, especially in order to criticize it, a speaker can use parody or caricature. Both are grounded in truth. But the two devices also exaggerate, thus veering into untruth. A comic's impression of a politician, for example, and a politician's ironic imitation of a rival will be accurate in some ways, but they will be distorted in others. Similarly, hyperbole is rooted in something real, but its intentional overemphasis of the truth is designed to evoke emotions and focus attention, not to convey literal meaning. A candidate's claim that a new tax will "ruin the economy" or that failing to pass a massive carbon tax poses an "existential threat to humanity" wouldn't pass fact-check muster. But these over-the-top declarations draw attention and provoke discussion. A related device known as "virtue signaling" (or "grandstanding") is designed to bolster the communicator's reputation in the eyes of a specific audience. By making a conspicuous public statement or using specific language, he attempts to ingratiate himself with a target group. So while the statement is primarily true on its face, it is also conveying additional meaning (for our purposes here, we can assume the communicator mostly believes the literal meaning of the statement — if he didn't, the statement would be a lie).

Advocates can also advance a specific story as a stand-in for, or an encapsulation of, a broader issue. The story's verisimilitude and generalizability are key — it appears to be true on its face, and it represents a more general phenomenon. Marie Antoinette is said to have remarked "let them eat cake" when told French peasants had no bread, illustrating her coldness toward the struggles of the poor. Gandhi is credited with saying "be the change you wish to see in the world," which encourages each of us to think about and pursue the good. Galileo reputedly said "and yet it moves," a defiant response to the Church's rejection of his theory about the Earth's motion. Evidence suggests each of these quotes is likely apocryphal. Yet because they speak to truthful elements about each individual — the French monarchy was corrupt, Gandhi was a force for good in the world, Galileo was courageous — they are believable, and thus convey some non-literal meaning.

Shelby Steele, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, recently coined the term "poetic truth" to describe this kind of anecdote when it serves one's politics or ideology. Though the notion has gained salience in recent years, its use is older than our republic itself. The Boston Massacre — which, according to some American observers, led to the deaths of five innocent colonists at the hands of ruthless British soldiers — fomented revolutionary zeal. Coverage of Spain's sinking of the U.S.S. Maine fueled American anger about ongoing Spanish aggression. More recently, Trump's claims that the 2020 election was stolen embody grievances about years of perceived unfair treatment at the hands of progressives, deep-state actors, and the media. Progressive claims that Trump had been compromised by Russian intelligence spoke to Trump's history of questionable business dealings and his threat to governing norms.

Each of these stories speaks to some greater political narrative. And yet, they are all mostly untrue. Boston citizens had been violently harassing the British soldiers prior to the gunfire. Studies indicate the Maine might not have been sunk by a Spanish mine. The 2020 election was not stolen from Trump, nor had a foreign adversary turned him. As Steele argues, the popular narrative about the details of Michael Brown's killing by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, was refuted by several investigations. But the story spoke to the general problems of law-enforcement misconduct — which the U.S. Department of Justice documented in its scathing report on Ferguson's police department — and violence against unarmed black men.

In each instance, backers of the story in question might care less about its veracity than about the bigger narrative it represents. Oftentimes they will respond to doubt about the incident by focusing on the narrative instead: "The British were ruthless!" "The Spanish were brutal in the Americas!" "Elites did try to destroy Trump's presidency!" "Trump is dangerous!" "Police violence against black men is real!" This puts poetic truths in a precarious position in Figure 1 — though the stories convey meager literal truth, they often convey some non-literal meaning that may be either wholly or partially true.

A form of communication related to the poetic truth is a subplot of a conspiracy theory — a small story that supports a broader conspiratorial narrative. Conspiracy theories — the broader accounts — hold that distant, largely invisible forces (often a group of powerful, wicked individuals) control an event or set of circumstances. Examples include claims that President John Kennedy's assassination was orchestrated by an array of domestic and foreign leaders, that the Pearl Harbor and 9/11 attacks were "inside jobs," and that Americans never landed on the moon. A specific subplot of the larger narrative — the claim that planted explosives brought down the Twin Towers or that no plane hit the Pentagon, for instance — is intended to corroborate the broader account. As with poetic truths, supporters might concede that the specific incident isn't entirely accurate while maintaining that the larger account of a secretive, nefarious power is true. Unlike poetic truths, however, conspiracy-theory subplots serve a narrative lacking any meaningful veracity.

Lastly, in some instances, a statement may be literally true (or close to it) on its face, but more is going on behind the text. A maxim, to take one example, expresses a specific truth while also conveying a rule of broader applicability. "Rome wasn't built in a day," "opposites attract," and "the sun will come out tomorrow" are all statements that tell us something valuable about construction, magnets, and astronomy, respectively; but they also teach us about patience, coalitions, and resilience. Faint praise is another example. If a reporter asks a candidate which of his opponent's attributes is most admirable, and he pauses and finally responds, "he's punctual," that statement might be entirely true (maybe his opponent is always on time), or it could be fabricated. But by choosing that insignificant strength as his opponent's best feature, he is conveying additional information.

Similarly, for writers working during periods of oppression, esotericism is an especially useful device. A writer afraid to explicitly state everything he believes will disguise some of his views in clever ways so that only select readers will understand his point. The literal meaning of most of his explicit text is true, but it is not the whole truth; more is conveyed "between the lines."

At times, a statement may have a narrow literal meaning while possessing greater additional content. Two types are especially common in politics and thus worth identifying. The first might be thought of as an "accurate allusion" — a statement that is true on its face while also referencing another source that provides additional meaning. Perhaps the best example is Abraham Lincoln's use of the phrase "[f]our score and seven years ago" in his 1863 Gettysburg address to discuss the Declaration of Independence. Literally, the statement was true; 1776 did occur 87 years before 1863. But the formulation he used to convey this fact is an allusion to a Biblical passage on a human's lifespan ("threescore years and ten"), which helps establish the speech's theme of a nation's lifespan. A century later, Martin Luther King, Jr., began his "I Have a Dream" speech by referring to the Emancipation Proclamation with the same formulation — "[f]ive score years ago" — which was both literally true and a meaningful allusion to Lincoln and the Bible.

The second type consists of true political statements that possess symbolic meaning. President Ronald Reagan's call for Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev to "tear down this wall" was literally about the dividing structure in Berlin, but it also referred to the insularity of the Soviet bloc. "Nevertheless, she persisted" was Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell's terse statement explaining why Senator Elizabeth Warren was not allowed to speak further — she had broken a Senate rule — but Warren's admirers appropriated the statement so that it came to represent the courage of women in public life.

The examples cited above demonstrate two lessons about the role of literal truth in political discourse. First, across the entirety of the veracity continuum — from outright lies to straightforward truth — there are extra-literal means of conveying meaning. Whether the statement is entirely true, partially true, or completely untrue, it can contain information that cannot be deduced from a mechanical parsing of the words themselves. If we are to be serious interpreters of political language, therefore, we cannot focus entirely on literal meaning.

Second, legitimate forms of political communication exist along the veracity continuum. Satire, aphorisms, parodies, hyperbole, and metaphors — all of which use untruth in different ways — should not be condemned outright. Consequently, the lack of complete literal veracity should not automatically disqualify a statement from being used in our discourse.

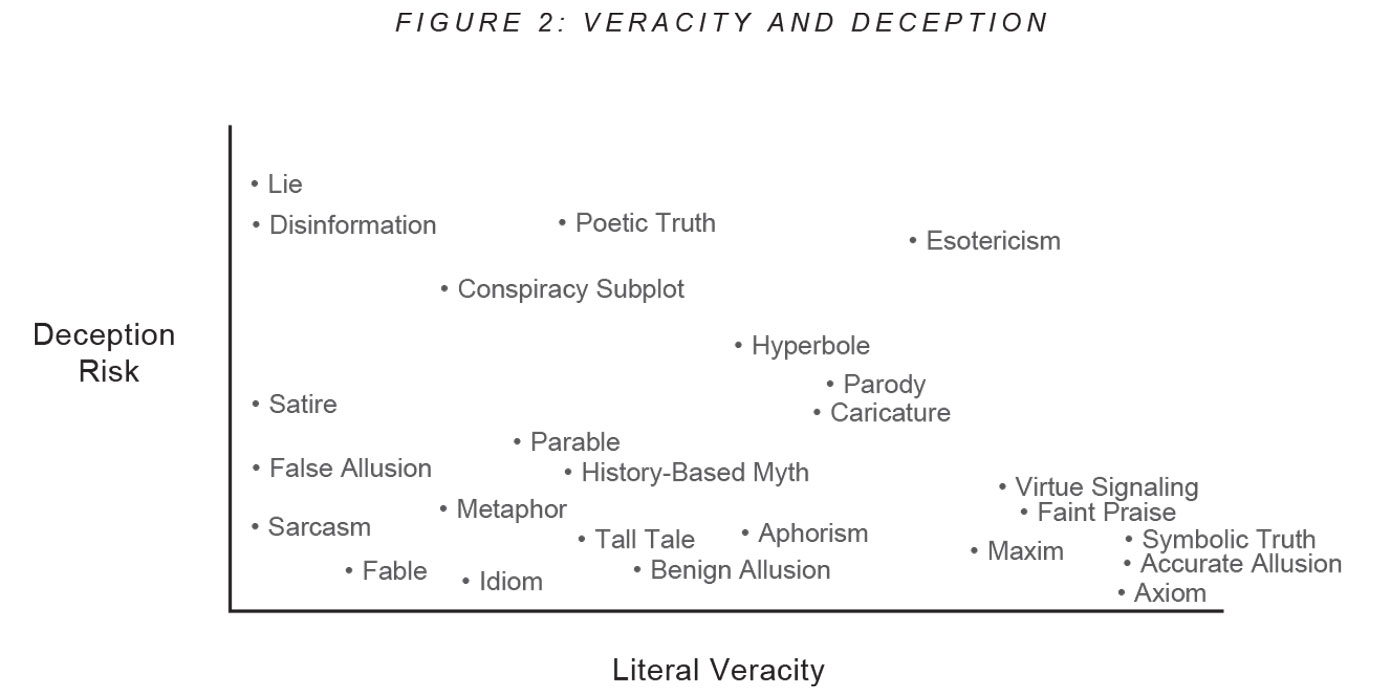

So does this mean that veracity doesn't matter? Of course not. Truth is still essential in the public's business. What it does mean is that the legitimacy of literal untruth or fiction can be thought to depend on two factors. The first is whether the statement's intention or likely consequence is deception. If either is the case, the statement becomes less legitimate. Second, the statement's legitimacy depends on which institution is responsible for making it. The cost to the public of a potentially deceptive statement skyrockets when it comes from an institution that is, or should be considered, authoritative. The more authoritative the institution, the less leeway it should have in making literally untrue or fictive statements, even if they speak to an underlying non-literal truth.

THE ROLE OF FICTION

Figure 1 presents a problem. We can see that a range of non-literal devices are acceptable in political discourse. In some instances, we tolerate statements that are literally false in their entirety (e.g., fable, satire, sarcasm) or in part (e.g., history-based myths, parody) because they convey extra-literal truth. But there are other fictions (e.g., straightforward lies) that we should find unacceptable. And we should not tolerate some literal falsehoods simply because they convey extra-textual meaning — we wouldn't celebrate a textbook that denies the existence of NASA, for instance, just because its author intends to advance the larger project of undermining the believability of the moon landing.

The key is to recognize the difference between fiction and deception. Fiction is understood here as invention or fabrication designed to transmit truth, not as false information masquerading as truth. Fiction can be used like a tool to communicate aspects about reality. Just as Aristotle understood that rhetoric could be used for good or malign purposes, we should appreciate that untruth can be used properly (e.g., to provide insight) or it can be misused (i.e., used to mislead). Myth and fable teach us about the continuities in the human condition; satire alerts us to the madness in front of us. But deception aims to convince us of something that is not real — for instance, that something that didn't happen actually occurred. So although a statement lacking literal veracity can have value, it sheds legitimacy when it intends to mislead or has the effect of misleading. A lie and a metaphor are equally untrue when read literally, but a liar intends for us to accept the literal meaning of the untrue words, while someone using a metaphor does not want us to believe that the world is literally a stage or that a coward literally has no spine.

As such, we can arrange the methods of communicating discussed above in a different two-dimensional graph (Figure 2), with literal veracity again along the X-axis but with potential for deception on the Y-axis. The X coordinates of each form are the same as those appearing in Figure 1, but the vertical dimension of each has shifted; we are now assessing whether an audience might be misled by each. The picture, therefore, differs from the first.

Most of these devices pose low levels of deception risk. In some instances, this is because the literal meaning is patently unbelievable. Few will take literally a story of a talking animal (fable) or immortals (myths), an extravagant comparison (metaphor), or clearly exaggerated characters or exploits (tall tales). Similarly, in the case of sarcasm, the communicator makes sure the audience takes away a message opposite to the literal meaning of the statement. An idiom, if taken literally, will seem bizarre to the listener (e.g., "under the weather," "break a leg"). Occasionally a listener will miss the additional meaning offered by faint praise, symbolic truths, and accurate allusions, so these forms of communication entail an increased risk of deception. Virtue signaling can also be modestly more deceptive because it can exaggerate the communicator's true beliefs. And yet, as with all of these examples, the latent meaning does not contradict the manifest meaning, and therefore the audience is not fundamentally misled.

Three generally safe devices — satire, parody, and caricature — do pose a marginally higher risk of deception. Smartly executed satire reels in an audience by initially seeming authentic; its early content and tone, therefore, tend to be believable. Then gradually, the content and tone shift, becoming more extreme and outrageous, illustrating how a view or practice is ridiculous. But audiences can be tricked by satire. Some people have mistakenly shared satirical articles with friends and followers online, believing them to be true. Organizations dedicated to "fact checking" have been fooled by satire as well, examining and then debunking patently silly claims. One particularly clever site has even satirized how fact checkers can be duped by satire. Similarly, parody and caricature hook the audience with a baseline of believability before moving on to spoof, but some people can be taken in by the initial believability. Tina Fey's impression of Sarah Palin was so convincing that many people came to believe Palin actually uttered the phrase, "I can see Russia from my house." Chevy Chase's impression of Gerald Ford persuaded America the president was clumsy even though he was an accomplished athlete. There is even a concept called "Poe's Law," which points out how it's often difficult to distinguish parody and sincerity about extreme views — especially online — if the author doesn't state his intent.

Hyperbole, too, can mislead if the audience doesn't recognize the exaggeration as such. Were a leader to say, "we have, by far, the most powerful military in the world," and the statement was intended merely as bravado, it could nonetheless lead to provocative international behavior and massive military losses if taken literally. Trump infamously wrote of "truthful hyperbole" in his book The Art of the Deal — a way to make people believe outlandish things by playing to their fantasies. Perhaps that's fine when discussing a three-night stay at a casino, but when a president repeatedly says that a deadly virus will disappear, people might believe him and behave in ways that endanger themselves and others. When a president repeatedly claims — falsely — that an election was stolen, people might believe him and storm the Capitol.

The most dangerous examples — and obviously so — are lies (which are designed to directly deceive), disinformation, and conspiracy subplots (both of which deceive literally and aim to support greater deception). Although esotericism and poetic truths are deceptive, because they make some use of the truth, they are more complicated than outright lies. Still, they can be destructive. Esotericism can be risky because it hides from the general audience content that the author is afraid to share publicly. Although most of the literal meaning of the text is truthful, some amount of disguised content is at odds with the text. So while a small audience will understand the message hidden between the lines, the observable content is meant to deceive most readers.

Poetic truths can be especially dangerous, since they use a specific story that is either wholly or partially untrue to support a more general narrative, which itself might be either wholly or partially true. That the larger narrative has truth to it gives the specific story the appearance of truth, so the validity of the narrative can be used to substantiate untruths at significant costs. Spanish aggression in Central America did not mean Spain sank the Maine; the existence of sexual assault does not mean everyone accused of assault is guilty; the media's disdain for Trump doesn't justify every Trump charge of "fake news."

An insight from Hannah Arendt's 1967 essay "Truth and Politics" explains why this style of untruth is so damaging. "Factual truths," such as those describing an event or an individual's activities, are more vulnerable to manipulation than "truths" that can be deduced via reason. Factual truths (e.g., whether a meeting was held or a document was produced) are fragile, because the world could have been otherwise. Therefore, it is easy to rewrite history and make the story believable. In 2004, Dan Rather and CBS News ran a negative story about George W. Bush's Texas Air National Guard service based on forged memos that seemed plausible and fit a narrative. When the story began to unravel, the New York Times ran a headline calling the documents "Fake but Accurate" to summarize the views of the secretary who would have produced the documents had they been authentic. Yes, the evidence is manufactured, the secretary admitted, but those documents could have been real, since the information in them was generally true. As Arendt wrote, a liar can obliterate the truth by fashioning alternative stories "to fit the profit and pleasure, or even the mere expectations, of his audience."

In his essay "Slouching toward Post-Journalism," Martin Gurri shows how some media outlets' new financial models and commitments to particular political positions are causing them to prioritize agendas over objective facts. Citing the work of media critic Andrey Mir, Gurri argues that, rather than aiming to convey objective truth, some strands of journalism are now selling an agenda to consumers who share their beliefs. Pointing to the 1619 Project as an example, he suggests a new motto for this type of organization, one that reflects Arendt's concern: "All the news that's fit to reframe history." This sounds worryingly like poetic truth: replacing an inconvenient fact with a more convenient story that is not wholly true, and then successfully selling the falsehood to an audience because the lie fits the broader narrative the audience already believes.

Having sorted these varied communication devices based on dimensions of literal and non-literal veracity, as well as on their non-literal veracity and deception risk, we now face our final problem. Even though several of the devices discussed have some potential to deceive, they remain valuable in certain contexts. That is, we shouldn't want to end the use of parody, caricature, satire, hyperbole, esotericism, and, possibly in some cases, even poetic truth, as they serve a purpose despite their risks. But we need a way of making sense of the trade-offs between value and risk involved in using such devices.

INSTITUTIONAL INTEGRITY

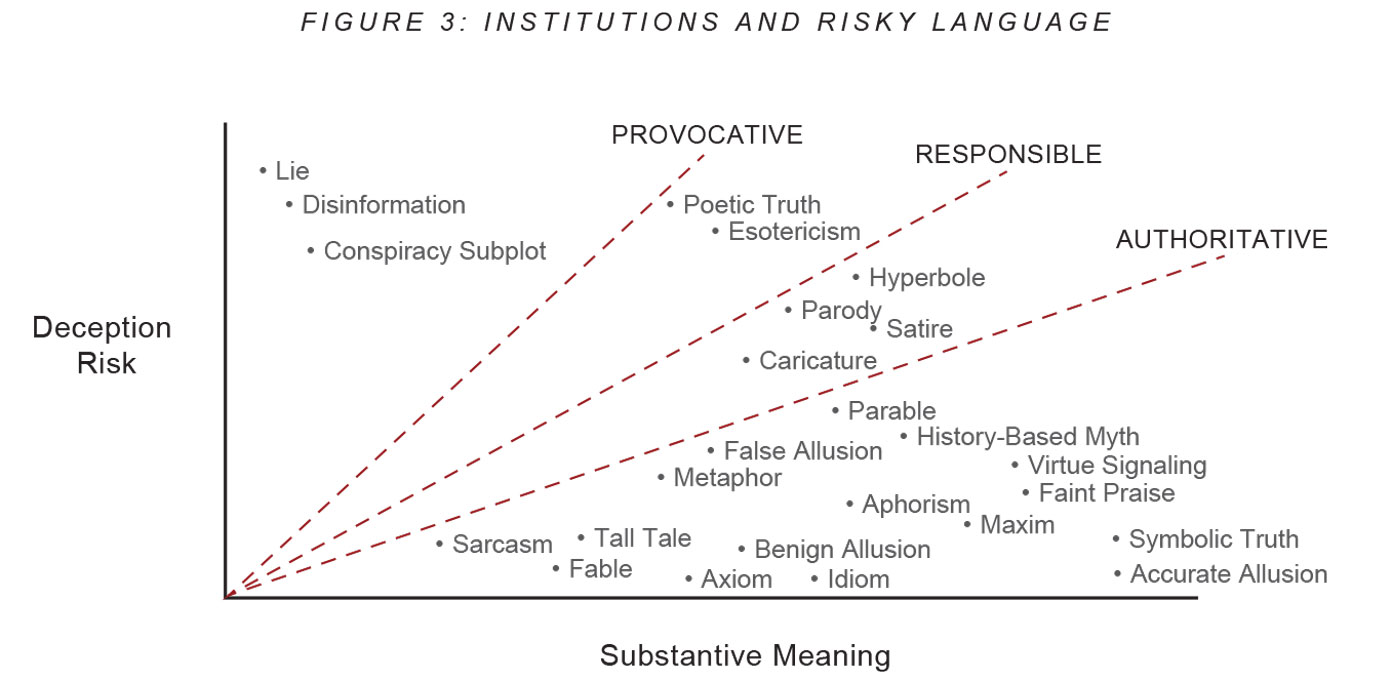

This dilemma leaves us with a final graph that considers each communication device along two dimensions. Again, deception risk will be on the Y-axis. But on the X-axis is an index called "Substantive Meaning," the sum of the two dimensions in Figure 1 (a form's literal veracity plus its non-literal meaning). Though certainly imperfect, its purpose is to approximate the amount of information that can be conveyed through each form based on facial reliability plus the meaning it offers between the lines.

It is essential to consider one other element in this analysis: which individual or institution is using the device. As a general rule, we should have different thresholds for different actors in public life. A free society needs social innovators, provocateurs, and polemicists to push the envelope, and because their value lies partly in advancing controversial ideas, connecting dots in new ways, and discomfiting authorities, we should tolerate their use of riskier forms of discourse. We should not accept anyone's use of the most dangerous communication forms — lies, conspiracy subplots, and disinformation — but we must remember that the most important social movements can be energized by radical ideas, symbolic messages, and poetic truths. Thomas Paine's radioactive writings, for instance, as well as the false stories about George Washington and the cherry tree, Betsy Ross and the first American flag, and the Pilgrims landing on Plymouth Rock, all serve a valuable purpose. We should therefore accept the risk of allowing some potentially misleading information to be conveyed in exchange for the value we glean from extra-literal content.

But we should make allowances for this kind of communication only when conveyed by those with unofficial or outsider roles. The more heavily the public relies on an institution for accurate, trustworthy information, the less appropriate it is for that institution or members of it to make use of devices posing the risk of deception. In fact, for some institutions — those that the public must be able to trust implicitly — certain forms should be entirely off-limits.

Figure 3 assigns each of the different communication forms a coordinate based on the amount of information it conveys via literal veracity and extra-literal content ("Substantive Meaning") and its likelihood of misleading the audience ("Deception Risk"). It also includes dotted lines for three categories of institutions. Below each line associated with a given type of institution are the respective devices that are permissible for it to use.

The most exacting rule applies to "Authoritative" institutions, such as government bodies and the news bureaus of major journalistic entities. Because it is so dangerous for these institutions to mislead the public, they should make use of only those forms of communication that are literally true, that contain fictions immediately recognizable to the audience (e.g., metaphors and fables), or that pose an insignificant cost if an audience misunderstands a fiction to be literally true (e.g., parables and aphorisms).

For "Responsible" institutions — such as those that employ political analysts, policy advocates, and opinion writers — more forms of communication are available. These institutions still must not purposely mislead. But because they serve to foster public debate, they should have access to devices that enable them to clarify, punctuate, and instigate, such as satire, parody, caricature, and hyperbole. None of these devices are meant to deceive, and the cost to the public is relatively small if the audience mistakes, say, a pundit's satire for truth. That cost is certainly smaller than the damage done to public deliberation if satire were prohibited. It's worth noting that political candidates, who need to punctuate and differentiate while demonstrating adequate preparation for serious public office, straddle the line between Authoritative and Responsible institutions.

Lastly, "Provocative" institutions — those employing social-movement leaders, political firebrands, and social critics — should be allowed to take the greatest liberty with veracity and make the most liberal use of extra-literal content. They will be the ones to deal in disguised messages for narrow audiences. They will weave together various incidents — perhaps playing faster and looser with the facts than many would like — to develop broader, yet hopefully true and insightful, narratives.

When this model of institutional differentiation is followed, powers and duties are sensibly arranged. Those in positions of great authority may possess a license to rule over certain domains (e.g., government entities) or have enormous influence over public knowledge (e.g., news organizations), but their clout is concomitant with constraints. Because they wield significant power, they must recognize their obligations: The public must be able to trust them, and they must behave in ways that earn and maintain the public's trust. Mainstream commentators, on the other hand, have the ability to use language in more creative ways as a means of contributing to public deliberation. They have the right to be taken seriously, but they do not have the right to rule. They also have no right to lie. Finally, fringe institutions may make the fullest use of language, testing the limits of tolerable discourse. They have the right to try to capture the public's attention and shape its thinking, but they have neither the right to rule nor the right to always be taken seriously.

In recent years, such arrangements have been disordered; so too has our public discourse. Institutions that should be authoritative have forfeited the right to be treated as such. President Trump was staggeringly dishonest on petty and serious matters alike, including the pandemic and the 2020 election. Some of his political allies, including elected officials, spread or defended his untruths, and continue to do so today. Meanwhile, media outlets large and small fanned the flames of various conspiracy theories and pursued political agendas often lightly supported by facts.

"Take it seriously, not literally" is a justifiable defense for some devices in public discourse. In fact, some legitimate ways of speaking and writing should not be taken literally at all. But purposely deceptive ways of communicating are illegitimate, and those that have a high likelihood of misleading the public must be eschewed by institutions required to be authoritative. For truth to prevail, our most important institutions must recognize and recommit to their solemn duty to avoid deceiving the public in their communications.

______________________

Andy Smarick is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. Follow him on Twitter here.

This piece originally appeared in National Affairs