The Other New York: Can Upstate New York Escape Stagnation?

Even prior to the pandemic-induced recession beginning in 2020, upstate New York faced stagnating economic performance and a declining labor force. This was despite Albany’s willingness to redistribute income from the much wealthier New York City metropolitan area to upstate, expensive but mostly failed state investments in advanced manufacturing, and the excellence of upstate universities.

This report details the current state of the region’s metropolitan areas and the changes in job growth over two business cycles, compares upstate New York to Ohio and Pennsylvania (nearby states with similar manufacturing histories but lower tax burdens), discusses the reasons upstate is stagnant, and elaborates on upstate’s assets and opportunities to regain economic and civic vibrancy.

Ultimately, upstate’s business environment is very important because with the population growing slowly overall, only a few U.S. regions can grow rapidly. New York State spends lavishly in many key categories (including elementary and secondary education, higher education, and some components of health care), but does not achieve results significantly better than nearby states that tax and spend less. For the region to become more competitive, the state needs to reduce the state and local tax burdens and abandon many of Albany’s attempts to pick business winners. Instead, the state’s efforts should be focused on encouraging research universities to collaborate with private businesses to keep graduates in the cities where they were educated, while supporting local efforts to make upstate cities and their surrounding rural areas more attractive places to live.

As of early 2022, there are some reasons to be optimistic. Upstate job losses as a result of the pandemic-related recession have been less severe than in the New York City area; there is a strong local movement to revitalize small upstate downtowns through better transportation and land use policies; and an aging population is generating job growth and security in industries like health care and social assistance, while long-ago investments in limited-access highways are paying off by attracting new goods distribution facilities. While upstate’s metropolitan areas are probably too small to attract rapid growth, a strategy focused on moderate gains seems achievable.

Introduction

In the recent past, New York State’s economic performance has been a study in contrasts, with New York City prospering until the pandemic-induced recession of 2020 and the state’s growth spreading moderately to the downstate suburbs. In comparison, upstate New York—most of the state by land area—stagnated, barely gaining private-sector jobs over the last business cycle from 2008 to the next peak in 2019.[1]

Both parts of the state lost jobs after 2019, but New York City, dependent on the largely vacated central business district and international tourism, was hit harder.[2] Yet New York City retains its inherent advantages as the nation’s largest and densest city and one of the most diverse labor markets.[3] It remains a magnet to many immigrants and well-educated young adults and an indispensable location for many types of business activity.[4]

This report focuses on the upstate economy and policies that can help it grow. Upstate, in contrast to the New York City metropolitan area, continues to be buffeted by many longterm trends that affect many other states as well, in particular the decline of manufacturing employment as a result of global trade and technological change.[5] Policies to spur economic and manufacturing growth implemented by the administration of former governor Andrew Cuomo did not turn that trend around, leading to scandal instead.[6] However, upstate did have significant employment growth in services, particularly health care and social assistance.[7] Much of the job growth was lost in the pandemic-induced recession.[8] A more recent trend is growth in transportation and warehousing employment, as upstate’s expansive highway network and favorable location in relation to population centers in the U.S. and Canada result in construction of large new distribution facilities.[9]

The service industry sectors that grew in the expansion phase of the last business cycle are concentrated in metropolitan areas. Most of these areas had population growth between 2010 and 2020. Agricultural employment also grew, albeit from a small base, and offers some prospect of stability in rural areas, which lost population during that decade.[10]

Observers of upstate New York’s long economic decline conclude that New York’s high taxes and burdensome regulations are an important contributing cause.[11] On the positive side, the state’s high per-capita income, compared to other states,[12] and its willingness to redistribute income from the much wealthier New York City metropolitan area to upstate,[13] create possibilities for investments in education and infrastructure that are more effective than the Cuomo era’s subsidies to businesses.

This report recommends that state and local policymakers pursue a path to greater economic dynamism upstate that includes three principal elements: first, sensible tax and budget policies; second, land use and transportation policies that revitalize downtowns by enabling market-driven urban densification; and third, efforts to forge stronger ties between colleges/universities and local businesses that can benefit from their expertise, avoiding expensive giveaways to attract large companies for which upstate offers no inherent business advantages. The 2022 gubernatorial campaign offers an opportunity to debate and discuss better policies going forward.

The State of Upstate

Upstate Job Growth Since 2008

When discussing job growth, it is best to compare two peaks in the business cycle. Every recession results in an acceleration of job losses in declining sectors of the economy, as businesses in these sectors can no longer sustain their historical level of operations. The recovery then results in a shift of capital and employment toward growing sectors, so the next peak of the cycle reflects a new, efficient distribution of employment among industry sectors. By comparing peaks, we see how the distribution of employment evolves over time.

This study sources employment data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), a data set compiled by state departments of labor of all employees covered by federal unemployment insurance.[14] Unlike the survey-based Current Employment Statistics,[15] the QCEW data are complete and not subject to sampling variability, although the data for Q2 2021 (the most recent figures available at the time of this writing) are considered preliminary and subject to revision.

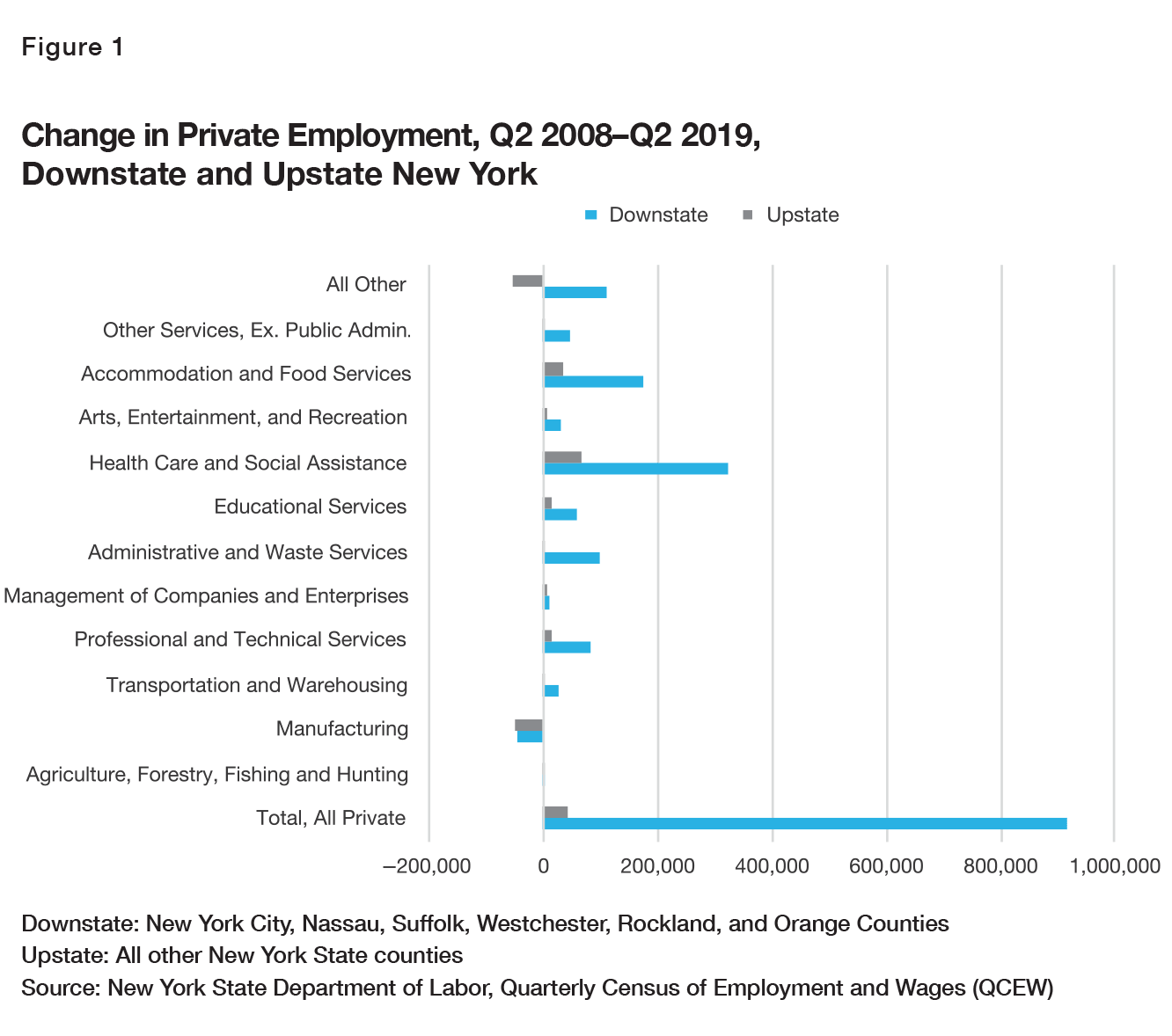

Figure 1 shows the change in average employment from the second quarter of 2008 to the second quarter of 2019 (second-quarter data are used to provide consistency in comparisons with the second quarter of 2021). In this period, which covers much of the recession that began in late 2007 and the subsequent recovery, private employment rose sharply in downstate New York but modestly upstate, by 41,000.[16]

The largest gainer among upstate service industries was health care and social assistance, adding about 65,000 jobs. Accommodation and food services increased by about 35,000 jobs. Professional and technical services and educational services both gained over 13,000 jobs. Manufacturing lost nearly 50,000 jobs, over 9% of the Q2 2008 total. Other large losers (combined in the figure as “All Other”) were retail trade (–22,500), wholesale trade (–12,800), and information/ publishing (–15,200).[17]

Between the second quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2021, employment growth turned sharply negative in downstate New York, as the region lost about 10.5% of its second-quarter 2019 private jobs (Figure 2). Upstate’s losses were less steep, at 5.9% of Q2 2019 private jobs. The largest job losses by sector upstate were in accommodation and food services, reflecting the contraction in tourism and restaurant meals, and in health care and social assistance.[18]

The increase in upstate private employment from Q2 2008 to Q2 2019 was offset by a fall in government employment (Figure 3). The biggest drop was in local government employment, which fell by 7.7%. In contrast, local government employment rose in the downstate area in the same period, entirely due to increases in New York City. From Q2 2019 to Q2 2021, local government employment fell both downstate and upstate.[19]

Job Growth in Upstate Metropolitan Areas

Most upstate employment is located in its 11 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) and in Dutchess and Putnam Counties.[20] As shown in Figure 4, only three of these areas (Albany– Schenectady–Troy, Buffalo–Niagara Falls, and Rochester) had significant private job growth between Q2 2008 and Q2 2019. The Albany area had the largest gain, just under 24,000, while the Buffalo area gained nearly 19,000 and the Rochester area about 14,000. Many other areas lost private jobs even in the growth phase of the business cycle. The situation was particularly grim in the Southern Tier, where the Binghamton MSA lost 8.7% of its private jobs and the Elmira MSA lost 11.2%. All the areas lost jobs during the post-2019 recession.

Employment growth in the Albany-Schenectady-Troy, Buffalo–Niagara Falls, and Rochester MSAs between Q2 2008 and Q2 2019 was dominated by services.[21] Albany-Schenectady- Troy was unusual in gaining manufacturing jobs; legacy manufacturer GE retains a substantial presence, and the second and third largest manufacturing employers in the area, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and GlobalFoundries, are Cuomo-era state aid success stories whose products experienced sharp increases in demand in the pandemic era.[22] The state’s Albany-area successes in identifying future successful manufacturing plants did not carry over to the rest of upstate. Buffalo–Niagara Falls had the most diversified gains in service jobs of the upstate MSAs, but lost manufacturing jobs, as did Rochester. Smaller MSAs that lost jobs overall still had gains in some services sectors.

Comparing Upstate New York to Ohio and Pennsylvania

Ohio and Pennsylvania are nearby states, and many of their metro areas have a heavy-manufacturing history similar to that of upstate New York, but lower tax burdens. In the Tax Foundation’s ranking of state and local tax burdens as a percentage of state income,[23] New York ranked first in 2019, the most recent year available. Its state and local tax burden was 14.1% of state income, well above the national average of 10.3%. Ohio and Pennsylvania were close to the average, at 10.3% and 10.4%, respectively, and ranked 19th and 16th among U.S. states.

Ohio has three significant MSAs—Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus—all much larger than any of the upstate New York MSAs. Columbus has had an outstanding metro economy, compared with other areas (Figure 5). It gained 113,000 private jobs from Q2 2008 to Q2 2019, or 14.7%.[24] The Columbus area lost jobs in manufacturing but had sizable, diversified growth in transportation and warehousing and multiple services sectors, including finance and insurance, management of companies and enterprises, health care and social assistance, and accommodation and food services. Columbus benefits from being both the state capital and the location of its flagship university. This provides stability in recessions and in turn has attracted major corporate headquarters. Interestingly, the Columbus MSA had more state employment in Q2 2019 (61,000) than the Albany area (48,700), and that number had grown since Q2 2008 in the Columbus area by 6,000 but fallen in the Albany area by 2,300.[25]

Cincinnati had more modest private job growth of 4.1% in the same period, similar to Buffalo’s, and also had diversified gains in transportation and warehousing and multiple services categories. Other Ohio MSAs had small gains or losses of private jobs overall, but consistently lost manufacturing jobs and gained jobs in health care and social assistance (6,600), as well as accommodation and food services (3,300), similar to upstate New York metro areas. Akron, for example, gained 1,300 private jobs overall but lost 5,000 manufacturing jobs.[26]

The Toledo area was an interesting outlier, because it gained manufacturing jobs, increasing by 4,100, or 9.6%. Manufacturing job growth in the Toledo area exceeded overall private job growth of 3,700 while health care and social assistance employment declined. Toledo, in Ohio’s northwest close to Detroit, is located within a day’s drive of the U.S. and Canadian industrial heartland. Its legacy automotive and glass-making industries have reinvested in the area, emphasizing technologically advanced processes and a highly trained workforce.[27]

Pennsylvania exhibited a pattern similar to Ohio.[28] Manufacturing job losses were widespread. Philadelphia and its suburbs grew strongly, with diversified growth in services. The Pittsburgh area grew moderately, also with diverse services growth. Smaller metros generally did not have growth in office-based services, but gained jobs in health care and social assistance and accommodation and food services. One notable gain was in the Scranton–Wilkes Barre–Hazleton area, which gained 7,400 jobs in transportation and warehousing between Q2 2008 and Q2 2019 and an additional 2,600 by Q2 2021. The area’s location at the intersection of multiple interstate highways likely underpins this growth.[29]

Why Is Upstate Stagnant?

The question of why upstate New York failed to grow substantially even in an economic upswing as powerful as the Q2 2008–Q2 2019 period when downstate prospered is critical to the state’s future. It’s as if a curtain were drawn across the Thruway north of Newburgh, bottling up investment to the south, similar to how American Revolutionaries stretched a chain across the Hudson River at West Point to prevent British ships from heading upriver.[30]

One consideration is whether upstate’s stagnation can be attributed to unique New York factors, perhaps related to the state’s high-tax environment. Writing in 2020, my Manhattan Institute colleague E.J. McMahon cited the state’s high taxes, as well as other impositions on businesses, such as workers’ compensation rates and a costly liability standard for construction projects.[31] He also noted the state’s minimum wage increases. These distinguish between New York City, Long Island, and Westchester, where the wage is $15 per hour, and the rest of the state, where it is now $13.20. Pennsylvania, in contrast, does not have a state minimum wage higher than the federal standard of $7.25 per hour. Ohio’s state minimum wage is now $9.30 per hour.[32]

The business group Upstate United (formerly Unshackle Upstate) in 2021 asked for a halt to minimum wage increases until the upstate economy had recovered; the minimum wage nonetheless was allowed to rise to $13.20 on January 1, 2022. The same group also asked for reforms in the state’s calculations of “prevailing wage” required for public construction projects and a moratorium on applying the state’s unique law that raises the cost of liability insurance for all construction projects.[33]

Offsetting the impact of the state’s high taxes and onerous regulations on upstate, however, is a sharply positive “balance of payments” with downstate. A 2011 Rockefeller Institute of Government report found that in the state’s fiscal year beginning April 1, 2009, New York City and the downstate suburbs combined accounted for over 72% of state revenues but only about 58% of state expenditures. The report breaks out the Capital Region separately from the remainder of upstate, and finds that both areas have substantial surpluses of state expenditures over state revenues.[34] A follow-up analysis in 2018 by former state assembly member Jim Brennan concluded that as a result of the city’s steep economic growth after 2010, its share of the state’s revenues had likely risen, while the distribution of expenditures was about the same.[35]

McMahon points out that the state’s spending included sizable, largely ineffective economicdevelopment subsidies to companies.[36] However, the relative similarity of upstate metro areas’ economic performance, compared with their peers in Ohio and Pennsylvania, may indicate that high New York taxes and high expenditures may, from an economic perspective, cancel each other out upstate. That’s hardly a defense of the arrangement; Ohio and Pennsylvania don’t have the opportunity to redistribute income from a superstar metro area as large as New York City. New York State does, but has largely squandered that opportunity.

McMahon also cites former governor Andrew Cuomo’s ban on the production of natural gas via hydraulic fracturing. This would have had the greatest effect on the Southern Tier, one of the most distressed parts of the state.[37] However, the employment benefits from “fracking” have been disappointing for Pennsylvania.[38] The Williamsport MSA, due south of Elmira, gained about 900 jobs in mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction from Q2 2008 to Q2 2019, and this gain has since fallen off by about 300. As in other small upstate New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio MSAs with declining manufacturing bases, the health care and social assistance sector has been a more consistent source of jobs, up 1,300 from Q2 2008 to Q2 2021.[39]

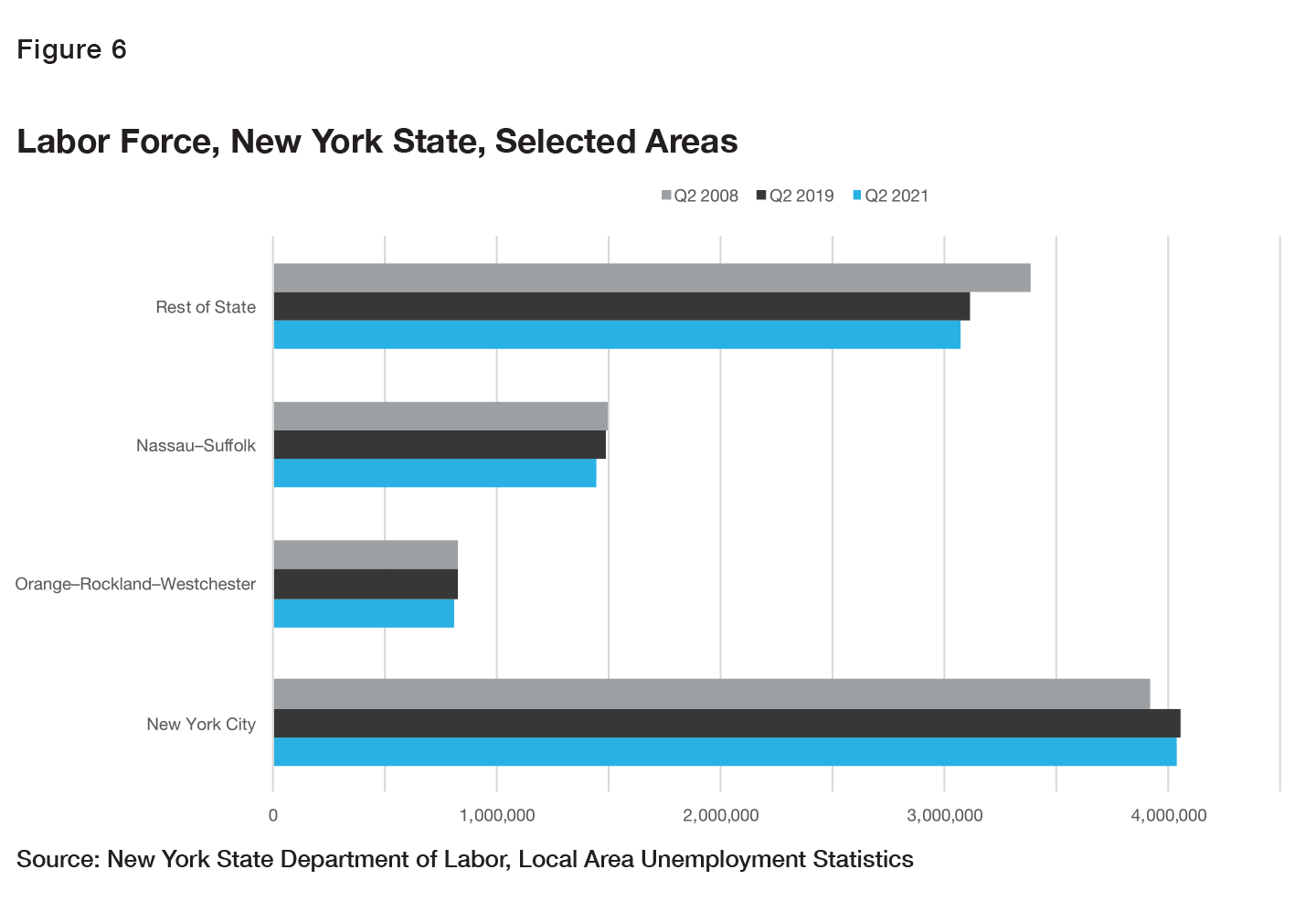

At a December 2019 briefing, before the pandemic-induced economic slowdown, Federal Reserve Bank of New York economists pointed to the decline in upstate New York’s labor force as a cause of its economic stagnation.[40] According to data from the New York State Department of Labor[41] (Figure 6), upstate’s labor force declined from 3.38 million in Q2 2008 to 3.115 million in Q2 2019, before the distorting effects of the pandemic, which reduced the labor force downstate as well.

Of course, the decline in upstate’s labor force is itself a consequence of stagnation. As businesses fail to create new jobs, workers who age out of the labor force are not replaced by younger workers. Instead, younger adults migrate to growing U.S. regions. The national trend in which the rate of population growth has declined, due to an aging population, declining births among women of childbearing age, and decreased international migration,[42] ensures that growing regions must add workers at the expense of declining areas. For younger workers contemplating a home purchase, moving to a booming area is a hedge against the possibility of falling resale prices in declining areas.

That still requires an explanation of why upstate is one of the stagnating parts of the nation. High taxes and regulation unfriendly to businesses are likely reasons. Another is that upstate lacks a metro large enough to provide a diversified labor market attractive to better-paid workers, for whom having a choice of potential employers without having to move is desirable. As we have seen with the New York City region, as well as Philadelphia’s role in Pennsylvania and Columbus’s in Ohio, the size and scale of a metropolitan area matter. Fast-growing metropolitan areas have a diversified mix of service businesses, as well as major colleges and universities and medical centers that are able to offer the opportunities and support the amenities that attract younger, well-educated workers and retain older professionals.

Midsize metros, like Buffalo and Pittsburgh, offer fewer opportunities but can still grow moderately as regional business hubs. The smaller metros are more disadvantaged and need to fall back on specific (though sometimes inadvertent) business advantages. The most obvious is an aging population, which leads to growth in health care and services to seniors, much of it federally funded through Medicare, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act and thus not dependent on the state’s business environment. Other advantages are geographic, such as Scranton’s location at the intersection of major interstate highways or Toledo’s in proximity to the U.S. and Canadian manufacturing heartlands. The past few years have seen a trend in and near upstate’s I-90 (Thruway) corridor of investments in large-scale distribution facilities.[43] Cheap land, relative to other northeastern locations near interstates, and a readily available labor force exiting declining manufacturing industries are cited as attracting these investments.

Other business advantages are made, like Toledo’s skilled manufacturing labor force and the willingness of its major employers to reinvest in advanced manufacturing. New York State has tried to create similar advantages for manufacturing in upstate New York, at great expense, but has mostly failed. McMahon points out that the one success has been in the Albany area, where New York State has successfully promoted the creation of a nanotechnology program at the state university and a heavily subsidized semiconductor industry.[44] As noted above, computer and electronic product manufacturing increased by about 3,000 jobs in the area since Q2 2008. However, other MSAs lost manufacturing jobs despite the state’s high spending on subsidies.

Why High-Tech Manufacturing Probably Won’t Be the Upstate Economic Development Solution

In the briefing book accompanying her January 2022 State of the State message, Governor Kathy Hochul spoke little of upstate economic development. She did propose “funding to support site-readiness investments to encourage semiconductor manufacturers to locate and grow in New York State. This funding ... would make New York an even stronger location to house a National Semiconductor Technology Center and additional chip fabrication plants.”[45]

Semiconductor manufacturing is part of the larger computer and electronic product manufacturing industry, which lost 8,900 jobs upstate between Q2 2008 and Q2 2019, according to state Department of Labor QCEW data, and an additional 950 jobs between Q2 2019 and Q2 2021. According to a recent report from the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), the U.S. share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity has fallen sharply in recent years.[46] The SIA is counting on U.S. government aid to turn this trend around.[47] The aid would come through the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act, supported by the Biden administration. The Senate-passed version would provide $52 billion to increase U.S. semiconductor production. The House bill, introduced in January 2022, matches the Senate commitment to semiconductor production.[48]

However, the major prospective beneficiary of this largesse in the Northeast is Ohio, not upstate New York. Also in January 2022, Intel and the state of Ohio announced a $20 billion investment to build two semiconductor manufacturing plants in Jersey Township in Licking County, part of the Columbus metropolitan area. The project could ultimately involve as much as $100 billion in investment and as many as eight plants for Intel and its suppliers and partners. Intel also committed to $100 million in partnerships with local educational institutions.[49]

The Intel announcement highlights that while the business environment is very important—the Ohio legislature passed special “megaproject” tax incentives in 2021 that Ohio Lieutenant Governor Jon Husted described as necessary to be “in the game”[50]—growth is also self-reinforcing. The Columbus metro already has the expanding labor force that Intel and its partners need, and the amenities to attract experienced managers and highly skilled workers. Given the zero-sum nature of U.S. regional growth, it’s likely to draw workers away from slow-growth metros both in Ohio and in other parts of the Northeast, including upstate New York.

Hochul’s FY 2023 Executive Budget takes some steps to improve workforce preparedness and thus the state’s attractiveness to employers. Enrollment at the State University of New York has been declining for the past decade.[51] This decline has been concentrated among the SUNY community colleges, where enrollment fell from nearly 248,000 in fall 2011 to less than 161,000 in fall 2021. (Enrollment at the four-year colleges that are state-operated also fell, but much more gradually, from more than 220,000 in fall 2011 to less than 210,000 in fall 2021.)[52] This is a dismaying trend, since community college is a traditional entry point to skills training for lower-income New Yorkers. Hochul now proposes to expand eligibility for part-time students for the state’s Tuition Assistance Program (TAP). TAP is a grant award program for incomeeligible students. The number of enrolled credits required to be eligible for assistance at any SUNY, City University of New York (CUNY), or nonprofit college degree program is reduced from 12 to 6, and part-time students in workforce credential programs at community colleges are also eligible.[53]

Hochul also promised to develop a plan to transform SUNY into “the top statewide system of higher education in the country.” To start this transformation, the Executive Budget funds new engineering buildings at the University at Buffalo and Stony Brook University. These are to become SUNY’s flagship institutions, downgrading the erstwhile flagship campuses in Albany and Binghamton.[54]

The same budget document brags that in New York, “state and local funding per student for public colleges in New York State was ... 42 percent ... more than the national average … and higher than 44 other states.” Moreover, “two-thirds of public colleges’ total revenue per student comes from State and local support—10 percent higher than the national average and more than 38 other states.” However, the “average tuition and fees at the State’s four-year public institutions was ... 20 percent ... less than the national average ... and lower than 41 other states.”[55] In effect, state spending that could be used to improve academic programs or to increase aid to low-income students instead goes to subsidize tuition for high-income students who would likely pay more if they resided in neighboring states and attended those states’ public higher-education institutions. Thus, the total state subsidy to higher education needs to be larger, but up to now has failed to achieve the flagship-campus academic quality other states enjoy at lower levels of subsidy.

Big Government vs. Economic Development in Stagnating Metros

Higher education, in which the state spends lavishly but is still in need of a plan to achieve a first-rate state university system, is symptomatic of a larger problem: New York spends more than most and, in some cases, all states in many key categories. However, the results it achieves are not significantly better than states that spend less. Those states also tax less and can better attract businesses that are sensitive both to the corporate tax burden and to the amount of tax their employees would need to pay.

The governor’s Executive Budget proposes to accelerate cuts in “middle-class” tax brackets previously scheduled to take effect in 2025.[56] However, these tax cuts are designed to have more impact in the high-income downstate suburbs than lower-income upstate. The tax cuts were paid for with steeply progressive increases in the upper tax brackets that likely deter businesses from investing in the state.[57]

Local school aid and Medicaid account for more than half the spending in the state budget.[58] In education, New York was first in the nation in per-pupil spending for elementary and secondary education in 2019, the latest year for which comparative data are available.[59] In spending per $1,000 of personal income—a fairer comparison, since New York is a high-income state and needs to pay teachers more than poorer states—New York was still third, behind Vermont and Alaska. Hochul’s Executive Budget proposes school aid spending of $31.3 billion, up 7.1% from the previous year. Most of the new spending is for Foundation Aid, which is intended to allocate state funds equitably to school districts.[60] While laudable, this new spending should have come from reducing or capping aid to wealthy districts, which would have helped constrain overall spending.[61]

In 2019, pre-pandemic, New York State’s average scale scores for the National Assessment of Educational Progress were significantly below the national public average scale score for fourth-grade mathematics, and not significantly different from the national average for fourthgrade reading and eighth-grade reading and mathematics. Ohio and Pennsylvania each scored significantly higher than the national average on three of these four measures and at the national average on the other.[62]

Governor Hochul’s FY 2023 Executive Budget also proposes a 6.3% increase in Medicaid spending. [63] In contrast to school aid and Medicaid, proposed spending on agency operations is held to a 1.2% increase, and all other spending declines 1.3%. The proposed Medicaid budget increases are a complex combination of increased spending and cost-cutting measures.[64]

In 2019, the latest year for which data are available, New York was a high Medicaid spender per recipient, but not the highest among the states. New York ranked 10th on overall average spending per enrollee, 4th for senior enrollees, 7th for individuals with disabilities, 32nd for adults, and 47th for children.[65] The relationship among spending levels, needs, and health outcomes is complicated, as indicated by these wide spending disparities in relation to other states. New York State, for example, scores “weak” in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ assessment of “Access to Care.”[66] The Citizens Budget Commission comments on the proposed Medicaid spending that:

For upstate New York to become more competitive as a business location, the state needs to shrink the combined state and local tax burden, relative to the state’s personal income, so that the ratio of taxes to personal income becomes closer to that of neighboring states. In 2011, under the administration of former governor Andrew Cuomo, the state legislature enacted caps on local property tax increases outside New York City.[68] Given the fall in local government employment, these caps are likely effective in constraining local government spending overall. The state has also adopted spending caps for its two largest spending programs, aid to education and Medicaid. The school aid caps have existed since FY 2021 and currently hold increases to the 10-year average personal income growth. However, the FY 2023 Executive Budget acknowledges that the school aid increases exceeded the index for FY 2022 and will again in the 2022–23 and 2023–24 school years. Thereafter, they will resume growing at the rate of forecast personal income growth.[69]

The Medicaid cap is tied to a complex formula intended to reflect health cost inflation. State spending in recent years has exceeded the caps, and actions have been undertaken to control costs, some of which are not yet fully implemented.[70] The arcane details of the state’s efforts to constrain its own spending and that of local governments, along with future tax rate changes, ultimately determine whether its position improves in the annual state and local tax burden rankings.

Upstate’s Assets and Opportunities

Education and Human Capital

Perhaps the greatest legacy asset upstate has is a network of private colleges and universities complementing the SUNY campuses, many of them nationally significant in science and engineering education.[71] A 2011 analysis by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that, scaled for the size of the working-age population, upstate New York’s major university metropolitan areas produce graduates at a rate much higher than the national average. Ithaca is the most productive by this measure, and Albany, Binghamton, Syracuse, Buffalo, and Rochester were also all above average.[72] The study finds that these metro areas all produce more graduates than their local labor markets can absorb, with Ithaca and Binghamton particularly imbalanced in this regard.[73] Additional research by the same authors found that there is only a small increase in a region’s human capital as a result of higher production of graduates. (Human capital is measured as the proportion of the working-age population with bachelor’s degrees or higher.) This is obviously related to graduates’ propensity to out-migrate. However, “research intensity”—academic research and development expenditures per enrolled student—had a stronger relationship to increases in the metro area’s human capital stock. The researchers conclude that this indicates that “spillovers into the local economy” as a consequence of academic research “create demand for skilled workers.”[74] Applying this measure of research intensity to upstate New York metros, the authors find that Ithaca is again a standout, with Rochester, Albany, and Buffalo ranking in the top quartile nationally.[75]

While this research is over a decade old, more recent American Community Survey data from 2019 indicate that the human capital effects of having strong research universities in a region remain significant. The Ithaca metro’s working-age population is 57% college graduates or higher. The Albany and Rochester areas are at 39% and 37%, respectively; Buffalo and Syracuse are lower, at 33% and 32%. Comparable figures for Columbus and Pittsburgh are 38% and 36%. The national average is 33%.[76]

Faculty and students at these institutions are resources, and potentially entrepreneurs and workers, for local businesses. The Empire State Development’s Division of Science, Technology and Innovation (NYSTAR) funds 15 Centers for Advanced Technology (CATs)[77] and 13 Centers of Excellence (COEs)[78] at private and public colleges and universities. The CATs, designated for 10 years, promote “collaboration between private industry and universities in the development and application of new technologies.”[79] CAT projects require matching funds from private industry. COEs have a similar objective, but are required to match the state investment with university funds. Without a private match, COEs are able to work with smaller and new industries, including start-ups.[80] The NYSTAR programs were favorably evaluated in a 2020 New York State Comptroller’s Office audit that was much more critical of state high-tech aid administered outside this framework.[81]

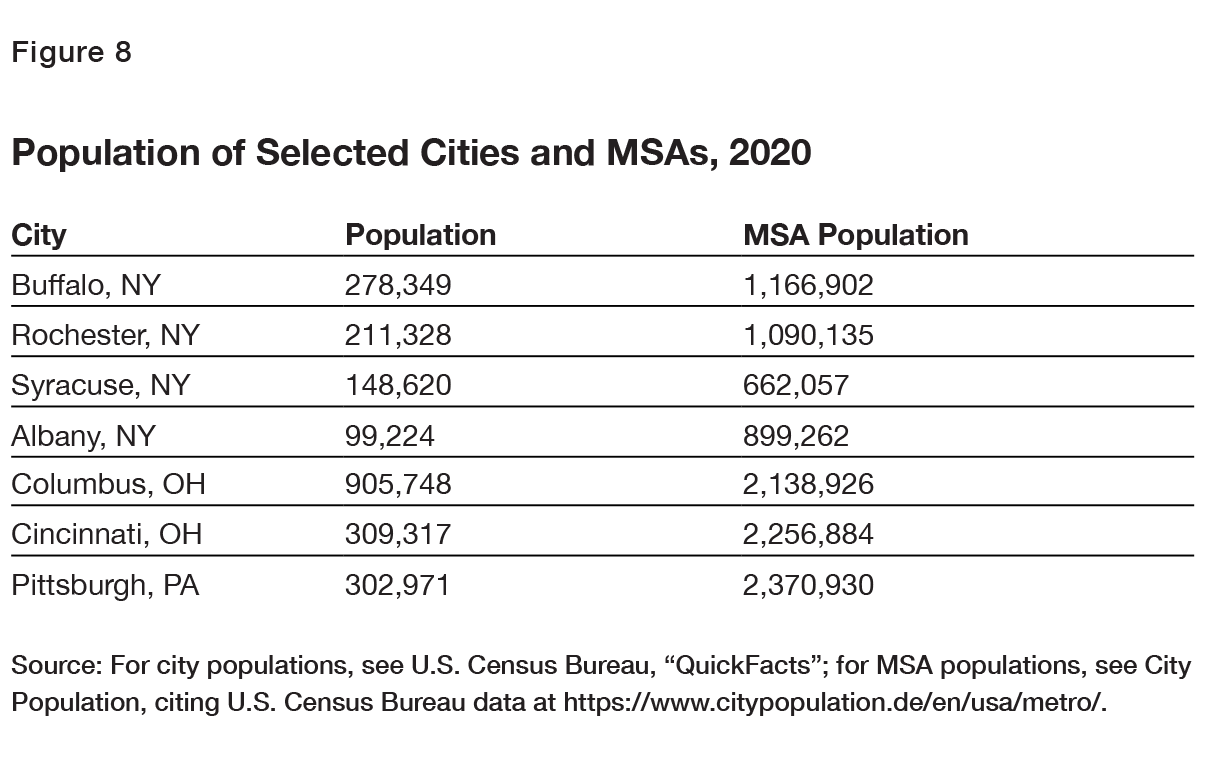

Upstate’s most notable legacy disadvantage is its growth pattern of multiple small cities, each greatly diminished in population from its peak. Compared with high-growth areas like Columbus, no city constitutes a labor market large enough to be attractive to many highly educated workers, who may be seeking a high level of urban amenities and job opportunities for equally qualified spouses. Upstate’s cities are distant enough from one another that crossing between labor markets is difficult. Upstate’s cities were once much larger, and have legacy institutions and infrastructure appropriate to their onetime size. Figure 7 shows the peak populations for major upstate cities.

Competing postindustrial cities are larger. Columbus, Ohio, for example, had a 2020 U.S. census population of 905,748; Cincinnati, 309,317; and Pittsburgh, 302,971 (Figure 8). Their MSAs are much larger than those in upstate New York.

Changing the Transportation Landscape

While upstate cities do not have good options to achieve rapid population growth, absent significant changes in national demographic trends, they can maximize their economic standing by building on the assets they have. Many upstate cities lost large numbers of housing units to urban renewal and highway building after 1950.[82] Along with the decline of major industries and the movement of population to the suburbs, these public actions left large areas close to downtown vacant or used for open parking and neighborhoods blighted by highway viaducts.

Downtown redevelopment can counteract past population losses and create an environment that attracts well-educated professionals who start, and work for, growing service-sector businesses. Increased working from home post-pandemic may also support urban revitalization, attracting big-city out-migrants for whom upstate’s low-cost housing and outdoor amenities are appealing.[83]

Another measure that could improve the economic competitiveness of upstate cities would be to improve transit linkages among downtowns, universities, other major employment centers such as hospitals, and large trip generators such as airports. Better transit lessens the dependence of downtowns on cars and permits the redevelopment of parking lots for more intensive residential or commercial uses. Today, local officials and community groups support the removal of highways as an important tool to achieve downtown growth. Where properly supported with zoning changes to allow dense growth and streetscape improvements, opening up land close to downtowns creates an opportunity to build housing, expand institutions, and create space for growing service businesses.

A recent article reviewing the nationwide interest in urban freeway removal cites the argument of a former planning director in Milwaukee, where a successful highway removal occurred two decades ago:

Governor Hochul’s budget proposal expresses support for several of these initiatives.[85] In Buffalo, officials and activists have expressed support for removing the Buffalo Skyway viaduct on the downtown waterfront and the Scajaquada and Kensington Expressways; the latter would restore the Delaware Park—designed by American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted—and the Humboldt Parkway between the Delaware and Martin Luther King, Jr. Parks.[86] The state has already committed to a traffic study of the Scajaquada, which carries less traffic than the other roads and seems more likely to be removed.[87] Hochul promised a study of fully or partially decking over the Kensington, an expensive proposition that may not satisfy activists who want it removed.[88] She did not mention the Buffalo Skyway proposal, which could create the most economic development potential by freeing downtown land from encumbrance by the viaduct.

Concurrently, the Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority is studying the extension of Buffalo’s light rail line to the main campus of the University at Buffalo in suburban Amherst and a parkand- ride facility at I-990 to the north.[89] The line now extends from downtown Buffalo to the university’s South Campus in the city of Buffalo. If the city of Buffalo and suburban communities are willing to permit denser housing growth along the light rail corridor, in addition to connecting major activity nodes, a well-planned expansion has the potential of diverting more transportation trips to transit. This might be a better use of public funds than decking over an operating limitedaccess highway, potentially requiring costly ventilation towers.

Hochul also proposed to undertake the second phase of the removal of Rochester’s Inner Loop freeway.[90] This would replace the Inner Loop North segment with a street-level boulevard, reconnecting communities and creating land for development. The Inner Loop East segment removal was completed in 2017.[91] In early 2022, residential and commercial developments and a museum expansion were underway on and adjacent to the former freeway segment.[92]

In Syracuse, Hochul committed to commence construction on the removal of the I-81 viaduct between Syracuse University and downtown, also to be replaced with a street-level roadway. This would also create new development sites as well as open space.[93]

In Albany, a plan by local activists would remove I-787 along the waterfront, replacing the road with a street-level boulevard and also freeing up land for public open space and development.[94] As with the Buffalo Skyway proposal discussed earlier, Hochul did not mention this proposal in her proposed budget.

Another potential upstate asset is the Empire Corridor, the historic rail route paralleling the Erie Canal that connects its major cities. The corridor’s passenger service has long been hampered by infrequent service, slow speeds, and conflicts with freight trains. A long-running study of the corridor by the state Department of Transportation remains incomplete.[95] Given the cost of upgrading the corridor and the institutional obstacles—most of the corridor is owned by the freight carrier CSX—incremental improvements are more likely than wholesale changes.[96] The governor has endorsed one project in the FY 2023 Executive Budget: the reconstruction of the 120-year-old Livingston Avenue Bridge across the Hudson River between Albany and Rensselaer.[97] If more people were living and working in upstate’s downtown cores, an improved rail corridor would become a more effective means of connecting metropolitan areas.

Conclusions

Upstate New York’s long stagnation continued in the last economic upswing ending in 2019. Modest job growth was focused in educational services, health care and social assistance, and accommodation and food services, while traditional mainstays such as manufacturing continued to lose jobs. Upstate’s labor force declined as well, as workers likely sought opportunity in fastergrowing parts of the country. Private job growth was concentrated in upstate’s three largest metros—Buffalo–Niagara Falls, Rochester, and Albany–Schenectady–Troy—while in smaller metros and rural areas, private employment barely grew or declined.

Since the pandemic-related recession began, upstate’s job losses have been less severe than downstate’s, but still indicate a slow recovery. One of the few positive signs has been a burst of private investment in large distribution facilities. Upstate’s proximity to many population centers in the U.S. and Canada and the availability of large sites at low cost, combined with the federal and state governments’ long-ago investments in the Thruway and other interstate highways, work in its favor.

However, upstate has largely failed to attract the investments in advanced manufacturing that state policy has sought, to replace the one-time anchor industries that made upstate cities manufacturing powerhouses. The nation’s heavy-manufacturing heartland has shrunk in size and is now focused well west of New York State. A major investment in semiconductor manufacturing has gone to the Columbus area in Ohio, which is larger and faster-growing than any upstate metro, offers more amenities, and has a more favorable tax environment.

Moreover, buying companies with public subsidies is expensive, uncertain, and fraught with the danger of corruption. There’s no reason to believe that the State of New York is on balance good at picking business winners. Upstate has a better chance of attracting service jobs to its urban areas. Health care and higher education are both major sources of jobs. Moreover, research universities’ collaboration with private businesses creates additional economic activity. Improving upstate urban cores can help keep graduates in the cities where they attended college and graduate schools. Remote working, which can take advantage of low-cost housing upstate, may become more attractive to well-educated professionals.

The nation’s slow population growth limits the number of metropolitan areas that can grow rapidly, and in New York State the downstate region is much better positioned to be one of those areas than any part of upstate. While upstate is likely to continue to be slow-growing, the State of New York can take actions that improve upstate’s relative competitiveness, in comparison to other slow-growing areas in the Northeast United States.

- The state should take actions that explicitly target the tax-burden gap with other states, calculated relative to personal income. These should include constraining spending increases and seeking savings to offset spending increases to improve deficient services. In particular, the state needs to reconsider its long-standing practice of maintaining high tax rates while also subsidizing the relatively affluent with benefits such as generous school aid and low university tuition. Neighboring states that eschew such practices offer a more attractive tax environment to business investors. New York is a high-income state and, even at ratios of taxes to personal income that are more in keeping with the national norm, could provide a robust social safety net. New York State also needs to address local spending mandates that keep taxes high as well as impositions on businesses that add costs not experienced by their counterparts in other states—such as those cited by E.J. McMahon and Upstate United.

- Upstate’s greatest asset is its large number of colleges and universities, including several that are nationally significant in science, technology, engineering, and medicine (STEM). These institutions’ national prestige ensures that they will continue to attract research funding and thus create the potential for beneficial relationships with the private sector. The state should pursue more effective spending to improve the academic quality of its flagship state university campuses, while charging tuition to those who can pay at rates comparable to nearby states. It should also continue its successful programs that facilitate and promote linkages between public and private institutions and upstate businesses.

- Upstate’s biggest disadvantage is that its cities are sufficiently widely spaced to function as distinct labor markets, none of which is large or deep enough to attract investments by major technologically advanced businesses like Intel’s in Columbus. Upstate cities were once much larger, and many were scarred by highway building, urban renewal, and parking development that effectively de-urbanized large parts of the central city. The state is pursuing, appropriately, highway deconstruction initiatives that create centrally located building sites that can restore vitality to upstate urban cores. More should be considered, along with rail service improvements on the intercity Empire Corridor and local transit improvements that reduce the need for downtown parking.

None of these measures will restore upstate to its onetime economic significance. However, in combination, these can generate moderate economic growth in upstate’s major cities, enabling them to improve local services and retain more local graduates. Stronger nearby cities would make rural living more attractive as well. Moderate growth is perhaps less exciting for politicians than spending lavishly in hopes of a dramatic turnaround. However, setting realistic goals is more likely to lead to success.

Appendix

The appendix provides data on job growth in upstate MSAs, with more detailed information on the three largest.

Albany–Schenectady–Troy MSA

The five-county Albany region mainly gained jobs in services from Q2 2008 to Q2 2019 (Figure A-1). Educational services gained 3,400 jobs, health care and social assistance gained 8,800 jobs, and accommodation and food services gained 6,800 jobs. Within health care and social assistance, most gains were in ambulatory health care services and hospitals; within accommodation and food services, about two-thirds of the job gains were in food services and drinking places.

In contrast to the overall upstate trend, the Albany metropolitan area gained manufacturing jobs as well. Job gains of 2,800 in chemical manufacturing and 3,100 in computer and electronic products manufacturing more than offset job losses in other manufacturing industries.

The Albany area’s post–Q2 2019 private employment losses just about offset its prior gains. However, the two growing manufacturing sectors sustained employment, and ambulatory health care services also continued to grow.

Buffalo–Niagara Falls MSA

The Buffalo metropolitan area, comprising Erie and Niagara Counties, lost manufacturing jobs in both the Q2 2008–Q2 2019 and Q2 2019–Q2 2021 periods. However, it had more diversified gains in services in the initial period (Figure A-2). Between Q2 2008 and Q2 2019, the Buffalo area gained office-based jobs in such sectors as finance and insurance (mainly insurance), professional and technical services, and management of companies and enterprises. As in the Albany area, the largest gains in services were in health care and social assistance and accommodation and food services. The health care and social assistance gains of 11,500 jobs were mainly in ambulatory health care services and social assistance, which includes home care agencies, senior centers, and child day care. In accommodation and food services, most job gains were in food services and drinking places. Services jobs also increased in arts, entertainment, and recreation and other services, which includes repair, household employees, and nonprofit organizations.

The earlier private job gains were erased by much larger losses after 2019. However, couriers and messengers, which includes express couriers, and warehousing and storage gained jobs, reflecting the shift to online commerce.

Rochester MSA

The Rochester area’s loss of manufacturing jobs was steep (–13,900) in the Q2 2008–Q2 2019 period, with the largest losses in chemical manufacturing and machinery manufacturing (Figure A-3). These losses continued after Q2 2019, during the pandemic.

The MSA gained jobs overall between Q2 2008 and Q2 2019 mainly due to growth in professional and technical services (5,200), educational services (5,000), health care and social assistance (14,300), and accommodation and food services (4,000). The largest component of health care and social assistance growth was in hospitals (6,900), while in accommodation and food services, all of the growth was in food services and drinking places (4,800), offsetting losses in accommodation.

After Q2 2019, job losses were widespread in nearly all industries. The one area of employment growth was in transportation and warehousing, concentrated (as in the Buffalo MSA) in couriers and messengers and warehousing and storage.

Smaller Upstate MSAs

Smaller upstate MSAs also exhibited the pattern in the Q2 2008–Q2 2019 period of job losses in manufacturing as well as gains in health care and social assistance and in accommodation and food services, even where private employment declined overall. Syracuse, for example, lost 2,600 private jobs overall and 6,600 in manufacturing. In contrast, the area gained 7,000 jobs in health care and social assistance and 2,300 jobs in accommodation and food services. Utica-Rome lost 1,600 private jobs overall from Q2 2008 to Q2 2019, including 1,200 in manufacturing. However, it gained 3,300 jobs in health care and social assistance and 1,500 jobs in accommodation and food services. The Binghamton MSA was hit even harder by private job losses in the period, losing 6,400 manufacturing jobs, but still gained 1,800 jobs in health care and social assistance and 1,200 jobs in accommodation and food services. The national downturn then reversed even the earlier gains, while declining industries continued to lose jobs.

About the Author

Eric Kober is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. He retired in 2017 as director of housing, economic, and infrastructure planning at the New York City Department of City Planning. He was Visiting Scholar at NYU Wagner School of Public Service and senior research scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at the Wagner School from January 2018 through August 2019. He has master’s degrees in business administration from the Stern School of Business at NYU and in public and international affairs from the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).