Testimony by Avik Roy Before the House Energy & Commerce's Subcommittee on Health

The following is a testimony delivered by Avik Roy before the House Committeee on Energy & Commerce's Subcommittee on Health. Read PDF here.

Transcending Obamacare: Achieving Truly Affordable, Patient-Centered, Near-Universal Coverage.

Introduction

There is no issue more important to the future of America than its long-term fiscal sustainability. And the long-term fiscal sustainability of the United States has been placed in jeopardy primarily by the structure and expense of America’s federally sponsored health insurance programs.

In addition, one of the principal economic challenges faced by middle- and lower-income Americans is the expense and instability of American health insurance. Health insurance keeps getting more and more expensive, forcing many families to choose between paying health care bills and buying other essential goods and services.

These problems, rightly, remain at the center of our public policy debate.

The ACA has dramatically increased the cost of individually-purchased health insurance

The Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010, sought to reduce the number of Americans without health insurance, primarily through two mechanisms: (1) expanding eligibility for Medicaid to all adults with incomes below 138% of the Federal Poverty Level; and (2) creating a network of health insurance exchanges, sometimes called “marketplaces,” to deliver regulated and subsidized private insurance coverage to those with incomes between 100% and 400% of FPL.

While the ACA has reduced the number of Americans who are uninsured, it has fallen far short of the Congressional Budget Office’s 2010 coverage projections, and has exacerbated several other long-standing problems with the U.S. health care system, most notably the high cost of American health insurance.

The ACA imposed significant regulatory changes upon the market for individually-purchased, or non-group, health insurance; i.e., those who do not obtain employer-sponsored or government-sponsored coverage, but purchase coverage on their own. These regulatory changes have dramatically increased non-group insurance premiums in most of the United States.

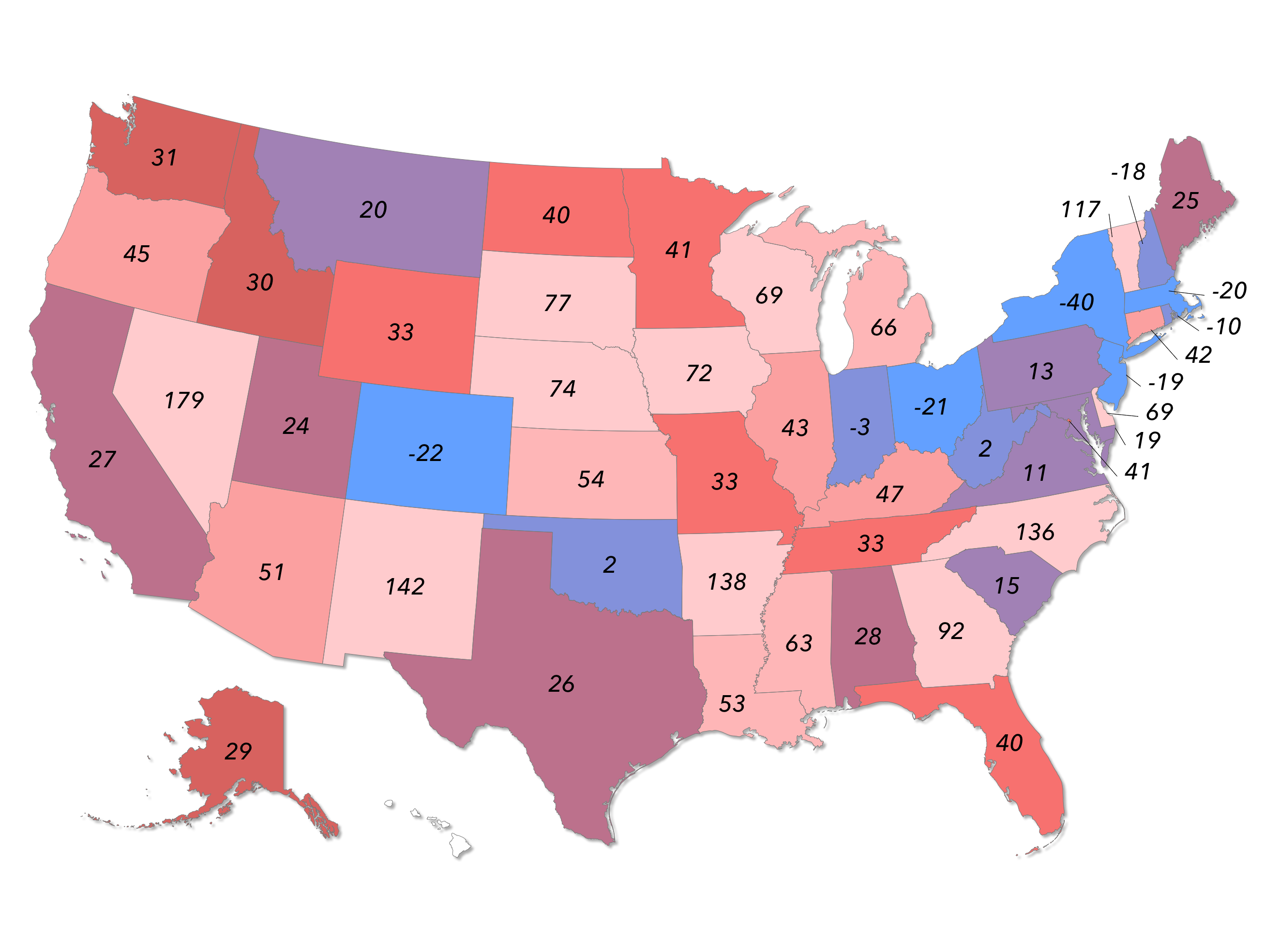

A Manhattan Institute study that I co-authored examined non-group health insurance premiums in 3,137 U.S. counties in 2013 (before the ACA’s regulatory changes went into effect) and 2014 (after they went into effect). It found that in the average county, the ACA’s regulatory changes increased non-group premiums by 49%. That 49% increase is adjusted to account for the ACA’s requirement that insurers offer coverage to those with pre-existing conditions; i.e., for those without pre-existing conditions, the 2014 premium increase was significantly higher than 49%.[1] ACA exchange-based premiums increased by an additional 5% in 2015[2] and 11% in 2016[3], on average, with large double-digit increases common in specific jurisdictions.

Figure 1. Change in Individual-Market Premiums Under ACA, 2013-2014 (Percent)

Rate shock in the non-group health insurance market. Prior to 2010, the market for health insurance purchased by individuals on their own was almost entirely regulated by states. The ACA added a new—and costly—layer of federal regulation upon this market. Many healthy individuals experienced rate increases of 100 to 200 percent. Even when taking into account those with pre-existing conditions, the ACA increased underlying rates in the average county by 49 percent. (Source: Manhattan Institute)

_____________________________________________

These rate increases were especially punitive for younger and healthier individuals. As a result, the ACA exchanges have largely failed to enroll these individuals, except in cases where their premiums were entirely, or nearly entirely, subsidized by federal premium assistance.

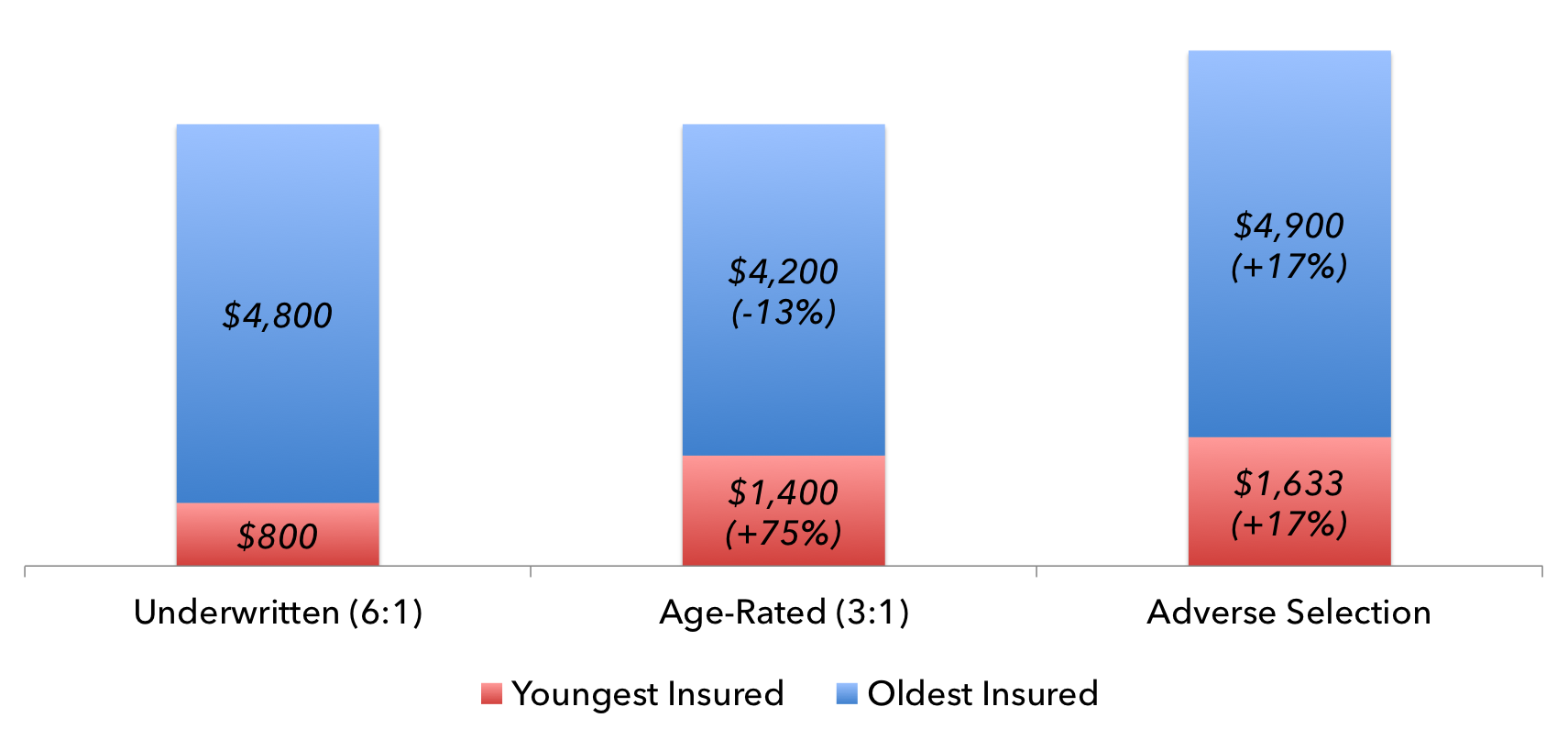

Figure 2. An Illustration of Age-Based Community Rating and Adverse Selection

Forcing the young to pay more drives costs up for everyone. The average 64-year-old consumes six times as much health care, in dollar value, as the average 21-year-old. Hence, in an underwritten (i.e., actuarially priced) insurance market, insurance premiums for 64-year-olds are roughly six times as costly as those for 21-year-olds. Under the ACA, policies are age-rated; i.e., insurers cannot charge their oldest policyholders more than three times what they charge their youngest customers. If every customer remains in the insurance market, this has the net effect of increasing premiums for 21-year-olds by 75 percent, and reducing them for 64-year-olds by 13 percent. However, if half of the 21-year-olds recognize this development as a bad deal for them, and drop out of the market, adverse selection ensues, driving up the average health care consumption per policyholder, thereby driving premiums up for everyone, including the 64-year-olds who were supposed to benefit from 3:1 age rating. In an attempt to mitigate this problem, the ACA includes an individual mandate forcing most young people to purchase government-certified insurance.

_____________________________________________

Because ACA-based premiums have been so high, enrollment in the exchanges has been significantly lower than expected. At the end of the 2016 enrollment period, the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation reported that 12.7 million individuals “selected, or were automatically reenrolled into, a 2016 Marketplace plan.”[4] If we assume a 15% attrition rate; i.e., those who select a plan but fail to pay the required premiums, we arrive at a 2016 enrollment of 10.8 million: a net increase of 1.7 million from 2015 levels, and far below the Congressional Budget Office’s 2010 projection that 21 million individuals would be enrolled in the exchanges in 2016.[5]

The ACA's Flawed ‘Three-Legged Stool’ Design

The high cost of ACA exchange-based coverage, and the resulting shortfall in exchange-based enrollment, was unsurprising to actuarial experts.

The ACA’s exchanges were built on a theory called the “three-legged stool.” First, a raft of federal regulations would be imposed on the non-group market, in order to redistribute premium costs from the sick to the healthy. Second, the ACA would impose an individual mandate, requiring most Americans to buy health insurance, in order to force healthy individuals to purchase coverage well in excess of their actuarial needs. Third, in order to mitigate the cost of mandated insurance coverage for low-income individuals, the ACA created a sliding scale of premium assistance and cost-sharing subsidies.

MIT economist Jonathan Gruber, in particular, has argued that each leg of the “three-legged stool” is essential to the proper functioning of the ACA’s insurance exchanges.[6] However, the three-legged stool theory has not been entirely borne out by the performance of the exchanges.

The ACA dramatically increased the cost of non-group health insurance for people with a low probability of consuming costly health care services. By far, the most damaging ACA regulation in this regard is age-based community rating, whereby insurers must charge their oldest customers no more than three times what they charge their youngest customers. On average, 64-year-old Americans consume six times as much health care, in dollar value, as the average 21-year-old. If both young and old people remain in the insurance pool—i.e., there is no adverse selection—21-year-olds face a premium increase of 75%. If younger individuals drop out of the market, premiums can increase by more than 100%.

In theory, the individual mandate’s fine should force these younger individuals to purchase health coverage, even if that coverage is far more expensive than their actual health care consumption. In reality, however, the ACA’s individual mandate is too weak, representing a fraction of the cost of ACA-based coverage. As a result, younger and healthier individuals have disproportionately avoided the exchanges.

Finally, for most Americans, the ACA’s sliding scale of subsidies do not fully offset the higher underlying cost of ACA-based coverage. For example, an individual whose premiums have increased by $100 per month, and is eligible for a $70 per month ACA premium subsidy, is still paying a net of $30 per month more in health coverage, even without considering the adverse impact of higher government spending on insurance subsidies.

Our work at the Manhattan Institute, and the work of others, indicates that the uninsured are highly sensitive to their net premiums, inclusive of subsidies. In 2015, 76% of those with incomes between 100 and 150% of FPL eligible for exchange-based coverage enrolled; but only 41% of those with incomes between 151 and 200% of FPL did. 30%, 20%, 16%, and 2% enrolled in the income ranges of 201-250% FPL, 251-300% FPL, 301-400% FPL, and over 400% FPL, respectively.[7]

Furthermore, the ACA’s system of means-tested subsidies has proven to be extremely difficult to administer, leading to a significant amount of waste, fraud, and abuse. It requires enrollees to estimate their future income on a rolling monthly basis, and then pay the government back if the Treasury department determines that they have underestimated that income (i.e., overestimated their eligibility for subsidies).

To extend the metaphor, the legs of the ACA’s three-legged stool are of different lengths. The regulatory leg is too long, driving up the cost of exchange-based coverage. The mandate leg is too short, encouraging healthier individuals to avoid buying unaffordable coverage. And the subsidy leg is too wobbly to correct the imbalances of the other two legs.

Principles of non-group health insurance reform

In contrast to the ACA, a robust non-group health insurance market will contain the following features, as discussed in the Manhattan Institute publication Transcending Obamacare: A Patient-Centered Plan for Near-Universal Coverage and Permanent Fiscal Solvency:[8]

- Put patients in control of their health care dollars. Individuals should enjoy a wide range of choices in the way their health coverage is designed. For example, they should be able to choose from a wide variety of financial payout structures (i.e. actuarial value) and a wide range of covered health care services (i.e. essential health benefits). Patients should have the option to pay for more of their health care directly, through health savings accounts and other instruments, instead of being dependent upon health insurance companies.

- Affordable premiums for young enrollees. A well-functioning market will not require healthy and/or young enrollees to pay gross premiums (i.e., prior to the impact of subsidies) that are significantly out of line with their near-term consumption of health care services (i.e., their actuarial risk).

- Voluntary participation. No one should be forced by Congress to purchase health insurance against their will.

- Affordable premiums and guaranteed coverage for sick enrollees and those with pre-existing conditions. Direct, transparent premium and cost-sharing assistance can provide affordable coverage to those with higher actuarial risk, without driving out the healthy and the young.

- Streamlined system of tax credits. The ACA’s convoluted system of direct and indirect subsidies should be replaced with a more transparent, tax credit-based system that reduces the incidence of waste, fraud, and abuse, while providing assistance to those in need.

- Gradual transition to the reformed system. Any replacement or reform of the ACA’s exchanges should ensure that ACA enrollees face minimal disruption to their existing coverage arrangements.

Transitioning to a reformed system

Congressional Republicans have repeatedly and consistently promised to repeal the ACA and replace it with a better system. A bill to replace the ACA that embodies the above reform principles should contain the following provisions:

- Reduce premium costs and expand patient choice. Congress should leave regulation of the design of non-group health insurance to the states wherever possible. It should allow for “copper plans” with a lower actuarial value, and offer other catastrophic coverage options. It should minimize the prescriptiveness of essential health benefits and cost-sharing limits, so as to encourage innovation in the design of affordable health insurance. It should improve the compatibility of exchange-based coverage with health savings accounts. It should repeal the ACA’s tax increases, including those that directly increase ACA-based premiums, such as the health insurance premium tax, the medical device tax, and the pharmaceutical product tax.

- Repeal the ACA’s discrimination against young enrollees. The ACA’s 3:1 age band should be repealed; insurers should be free to charge prices that fully reflect the age of their enrollees, in order to make coverage affordable for the young.

- Subsidized coverage for the sick and near-elderly. A reformed system should allow for tax credits to increase as enrollees get older, in order to compensate for the repeal of age-based community rating. A reformed system can preserve guaranteed issue and the prohibition against medical underwriting (i.e., requiring insurers to cover those with pre-existing conditions and charge the same prices to those of similar age regardless of health status) without an individual mandate.

- Repeal the ACA’s individual mandate. A well-functioning non-group insurance market does not require the constitutional injury of an individual mandate. The ACA’s mandate can be replaced with late enrollment penalties, a more limited open enrollment period, and the option of insurance contracts of two to five years instead of only one year.

- Means-tested, age-adjusted, tax-credit-based premium assistance. It is important for an ACA replacement to means test its health insurance tax credits. Some scholars have proposed a flat, uniform tax credit in which the poor and the wealthy receive the same amount of financial assistance. Such an approach is unwise, because it severely limits the amount of assistance Congress can provide to those near the poverty line. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the average exchange subsidy per subsidized enrollee in 2017 will be $4,550, and $4,670 in 2018.[9] By contrast, one widely circulated proposal to replace the ACA with a uniform tax credit would offer a subsidy of $2,100 to those in middle age, regardless of need.[10] Such an approach would be significantly disruptive to those with poor health status and/or low incomes, and would likely result in fewer people with health insurance relative to current law. Instead, a replacement for the ACA should preserve a sliding scale of means-tested tax credits, but do so based on income from the previous tax year. That way, the IRS has verified income data from which to base its tax credit calculations.

- Transitional considerations. Those who prefer to retain their existing exchange-based coverage, with existing subsidy levels, should be allowed to do so for several years, in order to minimize disruption to those on ACA-sponsored plans.

Impact of reform on federal spending and the uninsurance rate

If Congress were to reform the non-group health insurance market along these lines, the likely result would be more affordable coverage, and a larger number of individuals with health insurance.

Based on CBO-style fiscal modeling conducted by the Stephen Parente of the University of Minnesota and the Manhattan Institute, the reforms described above could reduce federal spending by $10 trillion over three decades. By 2025, it would increase the number of individuals with health insurance by 12.1 million, over and above current law. And it would reduce the cost of single health insurance policies by 18 percent over the same time frame.[11]

Once Congress has replaced the ACA with a better system for non-group coverage, it should consider expanding access to that market to people currently enrolled in Medicaid. Medicaid’s health outcomes are no better than those for individuals with no health insurance at all; access to a robust market for private coverage could significantly improve health outcomes for the poor, without increasing federal spending.[12] [13]

No one believes that the ACA’s health insurance exchanges were perfectly designed. The evidence is mounting that they were in fact quite poorly designed. The ACA’s shortcomings should not discourage Congress from striving to achieve the law’s stated goal: affordable health coverage for every American. That objective remains as important as ever, and Congress has the ability to make that goal a reality.

[1] Roy A, 3,137-County Analysis: Obamacare Increased 2014 Individual-Market Premiums By 49%. Forbes. 2014 Jun 18; https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2014/06/18/3137-county-analysis-obamacare-increased-2014-individual-market-premiums-by-average-of-49.

[2] Gonshorowski D, 2015 ACA-Exchange-Premiums Update: Premiums Still Rising. Heritage Foundation. 2015 Mar 20; https://thf_media.s3.amazonaws.com/2015/pdf/IB4366.pdf.

[3] Manatt, Phelps & Phillips. HIX Compare 2015-2016 Datasets. 2016 May; https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2015/12/hix-compare-2015-2016-da....

[4] HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Health Insurance Marketplaces 2016 Open Enrollment Period: Final Enrollment Report. 2016 Mar 11; https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/187866/Finalenrollment2016.pdf.

[5] Elmendorf D et al., Letter to the Hon. Nancy Pelosi. 2010 Mar 20; https://www.cbo.gov/publication/21351.

[6] Gruber J, Health Care Reform Is a “Three Legged Stool.” Center for American Progress. 2010 Aug 5; https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/report/2010/08/05/8226/health-care-reform-is-a-three-legged-stool.

[7] Pearson C, Exchanges Struggle to Enroll Consumers as Income Increases. Avalere Health. 2015 Mar 25; https://avalere.com/expertise/managed-care/insights/exchanges-struggle-to-enroll-consumers-as-income-increases.

[8] Roy A, Transcending Obamacare: A Patient-Centered Plan for Near-Universal Coverage and Permanent Fiscal Solvency. Manhattan Institute. 2014 Aug 13; https://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/transcending-obamacare-patient-centered-plan-near-universal-coverage-and-permanent-fiscal.

[9] Hall K, Federal Subsidies for Health Insurance Coverage for People Under Age 65: 2016 to 2026. Congressional Budget Office. 2016 Mar 24; https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51385.

[10] Anderson JH, A Winning Alternative to Obamacare. The 2017 Project. 2014 Feb; https://2017project.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/An-Obamacare-Alternative-Full-Proposal.pdf.

[11] Roy A, Transcending Obamacare: A Patient-Centered Plan for Near-Universal Coverage and Permanent Fiscal Solvency. Manhattan Institute. 2014 Aug 13; https://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/transcending-obamacare-patient-centered-plan-near-universal-coverage-and-permanent-fiscal.

[12] Roy A, Oregon Study: Medicaid ‘Had No Significant Effect’ On Health Outcomes vs. Being Uninsured. Forbes. 2013 May 2; https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2013/05/02/oregon-study-medicaid-had-no-significant-effect-on-health-outcomes-vs-being-uninsured/#4829d92173aa.

[13] Roy A, How Medicaid Fails the Poor. Encounter Books. 2013.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).