Streamlining Infrastructure Environmental Review

Many roads, bridges, sewers, pipelines, and other infrastructure need repair. New facilities should also be built where economic and social conditions warrant. Yet even where money is not an obstacle, the reviews that are required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) can be a significant source of delay. The average time to complete a final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), for example, was 5.1 years in 2016. Only 16% of them were completed in two years or less.

Lengthy reviews introduce uncertainty, add to the costs, and threaten the viability of infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, existing facilities continue to deteriorate as proposed upgrades or replacements wind their way through federal and state regulatory bodies. The problem is long-standing, and Congress has taken a number of steps over the last several years to streamline the process.

This paper assesses their effectiveness and proposes some additional changes, including:

- Updating rules and procedures at the agency level to exempt additional infrastructure projects from lengthy and complex review requirements.

- Expanding eligibility and giving agencies more flexibility to make use of NEPA’s “categorical exclusion” provisions.

- Assigning more environmental review duties to states. For more than a decade, a program called NEPA Assignment has allowed states to take the lead on shepherding certain highway and transit projects through environmental review. The states that have done so report reduced time required to complete environmental reviews. More states should be encouraged to participate. The federal government should expand the number of projects and actions that are eligible under existing authority, and Congress should expand the program to cover more kinds of infrastructure.

With the implementation of these recommendations, federal agency resources would be freed to deal with the complex projects that require more comprehensive review, reducing the time for projects that pass muster to begin.

Introduction

The 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)[1] requires federal agencies to review the potential environmental, social, and economic effects of proposed infrastructure projects that require some form of federal action—whether funding or granting permits—or that deal with federal facilities or land.

There are three levels of analysis under the NEPA framework. The largest, complex projects require the most comprehensive analysis, resulting in a final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). During 2008–12, agencies issued 1,125 of these statements.[2] Fewer than 1% of the projects subject to NEPA require an EIS. About 4% require a less comprehensive Environmental Assessment (EA). About 95% of NEPA analyses are categorical exclusions, which are faster and more streamlined.

Categorical exclusion determinations generally take only a few days, while the time to complete Environmental Assessments ranges from four to 18 months.[3] The average preparation time for an EIS was 5.1 years in 2016, up from about three years in 2000.

Categorical exclusion determinations generally take only a few days, while the time to complete Environmental Assessments ranges from four to 18 months.[3] The average preparation time for an EIS was 5.1 years in 2016, up from about three years in 2000.

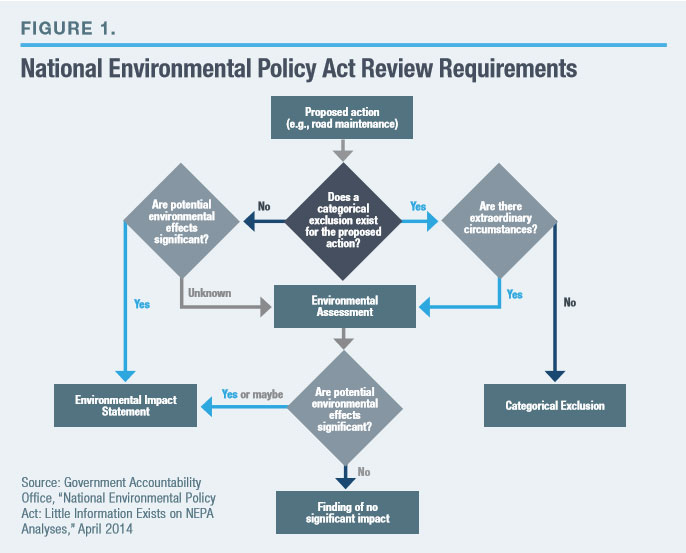

According to a Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, NEPA’s framework “can lead to confusion”[4] (Figure 1). It can also be the source of disputes or disagreements among different agencies and give outside groups in disagreement with NEPA procedures an opportunity to sue.[5]

With long review times, the viability of some projects is called into question, the health of existing assets can deteriorate further, and the deployment of new technologies can be delayed because the necessary infrastructure is not in place.

The federal government’s Permitting Dashboard shows the number and scale of many of the projects currently going through the NEPA process. As of May 2018, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) was the lead agency for 141 projects, while state DOTs were the lead in another 70.[6]

Of the final Environmental Impact Statements that were completed in 2015, only 16% were completed within two years. About 29% took longer than six years.[7]

The Progress of Reform

Beginning with a 2005 transportation act, Congress has sought to streamline and speed up environmental reviews. The two most recent laws are the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21), in 2012;[8] and the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST), in 2015.[9] The provisions in these laws include assigning more responsibilities to the states and expanding categorical exclusion determinations to allow for more projects to qualify. In addition, individual agencies have updated their rules to exempt certain actions from review requirements.

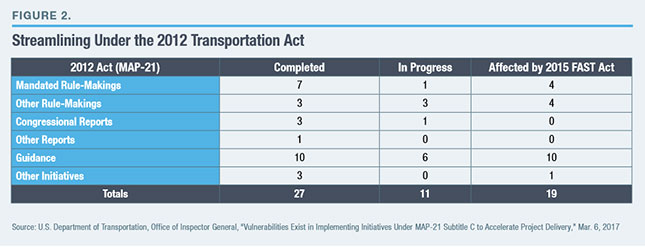

There have been some problems. As of March 2017, only 27 of 42 planned actions for implementing MAP-21 legislation had been completed.[10] FAST, intended to speed up projects, has, in some instances, led to delay, as many of the procedures called for in MAP-21 had to be revised in order to comply with the new law’s requirements. In total, 19 of the 42 rule-makings, guidance, and reports called for were altered, including 10 of the 27 actions already completed (Figure 2).

There have been some problems. As of March 2017, only 27 of 42 planned actions for implementing MAP-21 legislation had been completed.[10] FAST, intended to speed up projects, has, in some instances, led to delay, as many of the procedures called for in MAP-21 had to be revised in order to comply with the new law’s requirements. In total, 19 of the 42 rule-makings, guidance, and reports called for were altered, including 10 of the 27 actions already completed (Figure 2).

In addition to the legislative reforms, President Trump signed Executive Order 13807 on August 15, 2017. This order established the One Federal Decision framework, under which a single designated agency will shepherd each infrastructure project through the review and authorization process.[11] Instead of cooperating agencies conducting their own analyses and records of decision, the lead agency would coordinate with others on a single record of decision and serve as the point of contact for project sponsors when questions or problems arise.[12] The order gave the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ oversees the implementation of NEPA) dispute resolution authority in areas not already covered by previous legislation or executive orders. Importantly, Executive Order 13807 directs federal entities to establish a goal to reduce the time of review and authorization decisions for major infrastructure projects requiring an EIS to two years.

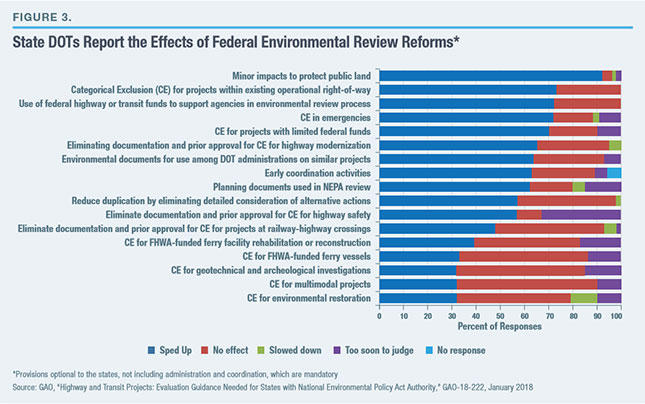

How effective have these various reforms been? A January 2018 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report[13] surveyed state DOTs regarding their use of a variety of some 31 provisions in federal legislation from 2005 to 2015 meant to speed up environmental evaluations of highway and transit projects. These included provisions that allow eligible projects to bypass some aspects of NEPA review, such as through the expansion of categorical exclusion determinations (Accelerated Review); provisions under which states can assume NEPA authority and undertake duties of environmental review and approval (NEPA Assignment); and provisions directed toward making the review processes themselves more effective, by establishing time frames or minimizing duplication (Administrative and Coordination Changes).

Of the 31 provisions, 17 are optional for states; and for 11 of them, the majority of participating state DOTs said that the provision had helped to speed up project delivery (that is, completion of government review and awarding a permit to begin work) related to NEPA review, while very few states indicated that the provision slowed the timetable (Figure 3).[14]

Of the 31 provisions, 17 are optional for states; and for 11 of them, the majority of participating state DOTs said that the provision had helped to speed up project delivery (that is, completion of government review and awarding a permit to begin work) related to NEPA review, while very few states indicated that the provision slowed the timetable (Figure 3).[14]

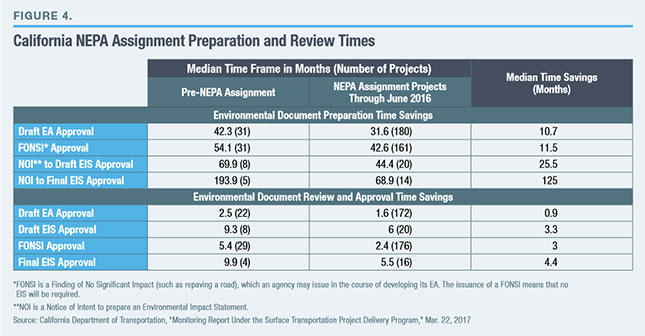

So far, six states have assumed authority for completing environmental reviews of highway and transit projects under the NEPA Assignment provisions, starting with California in 2007, followed by Texas in 2014, Ohio in 2015, Florida in 2016, and Utah and Alaska in 2017.[15] In its most recent report, the California Department of Transportation showed that it has been able to significantly reduce review times.[16] Before NEPA Assignment, approval of final EISs took a median of 9.9 months; that period has declined to 5.5 months. California also reports that the median time for draft EAs went from 5.4 months to 2.4 months (Figure 4). The time savings have been more substantial for document preparation. In the pre-NEPA Assignment baseline, the median time from filing a Notice of Intent to prepare an EIS to the approval of a final EIS was 194 months; this has declined to 69 months. Median times for preparation of other types of analysis also saw significant reductions of at least 10.7 months.

Texas has not yet started an EIS through NEPA Assignment, but its average EA completion times have declined from 2.5 years to 1.5 years.[17] Other participating states in the assignment program do not yet have enough data to provide estimates of times saved.

While provisions related to NEPA Assignment and Accelerated Review have demonstrated success in reducing review time, so far the majority of Administration and Coordination provisions have had either no effect on review and permitting times or the data are insufficient to make a judgment. Further improvements to Administration and Coordination in Executive Order 13807—most notably, the One Federal Decision framework—were put into effect only in April 2018.

While provisions related to NEPA Assignment and Accelerated Review have demonstrated success in reducing review time, so far the majority of Administration and Coordination provisions have had either no effect on review and permitting times or the data are insufficient to make a judgment. Further improvements to Administration and Coordination in Executive Order 13807—most notably, the One Federal Decision framework—were put into effect only in April 2018.

Next Steps

Nancy Sutley, the Obama administration’s first CEQ chairman, noted in 2010 that “we want to avoid the use of NEPA procedures that have become outdated with the passage of time, evolving technologies and changed circumstances.”[18] One recent, illuminating example is the small cell networks that are needed for 5G, the next generation of wireless broadband. Previous generations required large cell towers hundreds of feet tall, which were subject to NEPA review. In contrast, in many instances, 5G requires small cells about the size of a shoe box that can be fitted onto existing buildings—and 5G networks will require as many as 300,000 small cells over the next few years. Yet many small cell facilities still require Environmental Assessments through NEPA.[19]

The costs can be substantial: weighted average cost per small cell reviewed in 2017 was $9,730, accounting for almost 30% of total small cell deployment costs. Beyond monetary cost, compliance with review procedures and analysis completion times could add months to environmental review times.[20] The reviews for the vast majority of small cell deployments did not lead to any changes in planned deployments.[21]

In a recent vote, the Federal Communications Commission amended the rules so that the deployment of small wireless facilities by private parties no longer constitutes an “undertaking” or “major Federal action,” and therefore is no longer subject to the review requirements in NEPA.[22] Excluding these small cells from these federal review requirements could lead to savings of almost $1.6 billion over time, which would be enough for 55,000 additional small cell deployments.

Other federal agencies should review existing rules with an eye toward modernization, removing requirements that no longer make sense for evolving infrastructure.

Categorical exclusion determinations allow certain projects to go through accelerated review. These projects tend to be smaller, such as resurfacing roads. Projects can also qualify for categorical exclusion if they are for infrastructure repair or replacement in response to an emergency, or if the related activities would occur within an existing right-of-way, among other eligibility criteria.

MAP-21 included a provision that established a categorical exclusion for smaller surface transportation projects that either receive less than $5 million of federal funds or have a total estimated cost of $30 million or less, with the federal funds share of less than 15%.[23] The FAST Act indexed the thresholds to inflation.

Increasing the lower threshold to $10 million and the second threshold to $50 million, with the federal share component rising to 20%, would establish a uniform federal funding threshold of $10 million. Surface transportation projects between the current threshold and the new, higher threshold would be eligible for the faster review track. Further reforms should also explore expanding this categorical exclusion to other forms of infrastructure, such as projects related to water resources, airports, or wastewater management.

In the current NEPA framework, each federal agency proposes its own categorical exclusion based on a record demonstrating that the activity would not have a significant effect on the environment or people. Proposals have to be reviewed and approved by CEQ.[24]

Yet if one agency wants to make use of a categorical exclusion established for another agency, it has to go through its own approval and substantiation process. It would be better if federal agencies had the authority to make use of categorical exclusions approved for other agencies. For example, looking at existing categorical exclusions, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Department of Energy have both established a categorical exclusion for small-scale noise abatement procedures such as installing noise barriers near facilities.[25] These exclusions do not differ significantly in the substance, and the actions are uncontroversial. Even so, in order to establish the exclusion for energy infrastructure projects, the entire process had to be undertaken again. The varied steps included initial consulting with CEQ, consulting with other federal agencies, a public comment period, consideration of public comments, and review of public comments with CEQ—and only then, publishing the final categorical exclusion in the federal register and making it available.[26]

To encourage more states to participate in the NEPA Assignment program, the application process should be made simpler and clearer, and the related administrative burdens should be reduced. One way to do so: require only a simplified letter of interest from the state to FHWA, followed by a checklist of necessary steps for eligibility. In the current process, even before application, the state has to go through a coordination meeting with FHWA and undergo a public comment period. The state then puts together a draft version of an application and shares it with a working group of FHWA entities for review; the state may have to go through multiple revisions, adding to the total application time.

States are also required to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding with the federal government, with the maximum term being five years, after which the agreement has to be renewed. Similarly, federal agencies currently conduct an annual audit for the first four years of participation to ensure that the state is in compliance, with more limited reviews thereafter.[27] Increasing the maximum length of a Memorandum of Understanding and requiring fewer years of audits would reduce administrative burdens for participating states while still ensuring that they are in compliance.

The scope of actions included in NEPA Assignment should also be expanded to include duties such as noise-policy or floodplain determinations. If federal actions that currently serve as a roadblock for infrastructure projects in a state were brought under the purview of the assignment program, it would be another reason for states to consider participation.

The authority for NEPA Assignment includes railroad, public transportation, and multimodal projects, in addition to highway projects; but so far, states have not made use of this authority.[28] Federal entities should explore why this is the case as well as how to expand assignment to these areas.

NEPA Assignment is currently limited to infrastructure projects under the authority of FHWA and the Federal Transit Administration. Further reforms should expand the program to other types of infrastructure—such as energy, water, or communications—as suggested in the Trump administration’s legislative outline.[29]

Endnotes

- The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended (Pub. L. 91-190, 42 U.S.C. 4321-4347, Jan. 1, 1970, as amended by Pub. L. 94-52, July 3, 1975, Pub. L. 94-83, Aug. 9, 1975, and Pub. L. 97-258, § 4(b), Sept. 13, 1982).

- Government Accountability Office, “National Environmental Policy Act: Little Information Exists on NEPA Analyses,” April 2014, p. 8.

- Ibid., p. 19.

- Linda Luther, “The National Environmental Policy Act: Background and Implementation,” CRS, Feb. 29, 2008.

- Some states have their own environmental and permitting review requirements. See Government Accountability Office, “Highway Projects: Many Federal and State Environmental Review Requirements Are Similar, and Little Duplication of Effort Occurs,” November 2014.

- Only certain infrastructure projects are required to submit information to the dashboard. See Permitting Dashboard, “Project Status by Lead Agency.”

- National Association of Environmental Professionals, “Annual NEPA Report 2015 of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Practice,” August 2016, p. 17.

- Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act, Pub. L.112-141.

- Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act, Pub. L. 114-94.

- U.S. Department of Transportation, “Vulnerabilities Exist in Implementing Initiatives Under MAP-21 Subtitle C to Accelerate Project Delivery,” Mar. 6, 2017.

- Executive Office of the President, “Executive Order 13807: Establishing Discipline and Accountability in the Environmental Review and Permitting Process for Infrastructure Projects,” Aug. 15, 2017. See also Philip Howard, “Modernizing NEPA for the 21st Century,” House Committee Natural Resources, Oversight Hearing, Nov. 29, 2017, and idem, “Improving America’s Infrastructure,” Manhattan Institute, Apr. 18, 2018.

- In April 2018, 12 federal agencies signed a Memorandum of Understanding, putting the executive order into effect. Executive Office of the President, “Memorandum of Understanding Implementing One Federal Decision Under Executive Order 13807,” April 2018.

- The Advance Planning category is not discussed because it is outside the scope of this paper. GAO, “Highway and Transit Projects: Evaluation Guidance Needed for States with National Environmental Policy Act Authority,” GAO-18-222, January 2018.

- Of the 17 optional provisions, eight establish a categorical exclusion designation. These designations range from projects to repair damage to transportation assets due to emergencies to smaller projects with limited federal funds, among others. Three additional provisions eliminate documentation and prior approval requirements for existing categorical exclusion designations—for example, highway safety–related actions such as installation of lighting. Five other provisions authorize enhanced coordination between government entities, the incorporation of environmental documents from other projects, or the use of funds to support review processes. Finally, the provision concerning “minor impacts to protected public lands” authorizes a historic site, parkland, or refuge to be used for a transportation program or project if it is determined that “de minimis” impact would result.

- GAO, “Highway and Transit Projects: Evaluation Guidance Needed for States with National Environmental Policy Act Authority,” GAO-18-222, January 2018.

- California Department of Transportation, Division of Environmental Analysis, “Monitoring Report Under the Surface Transportation Project Delivery Program,” Mar. 22, 2017.

- GAO, “Highway and Transit Projects,” p. 29.

- Executive Office of the President, “White House Council on Environmental Quality Issues Guidance to Help Federal Agencies Ensure the Integrity of Environmental Reviews,” Nov. 23, 2010.

- Federal Communications Commission, “FCC Fact Sheet: Wireless Infrastructure Streamlining Report and Order,” WT Docket No. 17-79, Mar. 1, 2018. As the order references, the National Historic Preservation Act also introduced substantial burdens related to review and compliance for these small cell structures. While the order will contribute to reducing burdens at the federal level, other legislation, such as the Davis-Bacon Act, which requires contractors and subcontractors on federally funded or assisted contracts to pay the local prevailing wage, substantially increases labor costs for infrastructure projects.

- Accenture, “Impact of Federal Regulatory Reviews on Small Cell Deployment,” Mar. 12, 2018.

- Brendan Carr, “New FCC Rules Could Lead to More Broadband for More People,” Baltimore Sun, Mar. 20, 2018.

- FCC, “Wireless Infrastructure Streamlining Report.”

- Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), “Action: Categorical Exclusion for Projects of Limited Federal Assistance,” Jan. 28, 2016.

- See, e.g., FHWA, “NEPA Classes of Action,” Environmental Review Toolkit, accessed May 23, 2018.

- Department of Energy, “Categorical Exclusion Determinations: B1.21 Noise Abatement,” accessed May 23, 2018; FHWA Categorical Exclusions, 23 C.F.R. § 771.

- CEQ, “Final Guidance for Federal Departments and Agencies on Establishing, Applying, and Revising Categorical Exclusions Under the National Environmental Policy Act,” Federal Register, Dec. 6, 2010.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- FHWA, Environmental Review Toolkit, “NEPA Assignment: Program Assignment,” accessed Mar. 5, 2018.

- Executive Office of the President, “Legislative Outline for Rebuilding Infrastructure in America,” Feb. 12, 2018, p. 47.

______________________

Charles Hughes is a policy analyst with Economics21 at the Manhattan Institute. Follow him on Twitter here.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).