Finding Room for New York City Charter Schools

Former mayor Michael Bloomberg championed charter schools and accelerated their growth via colocation, the granting of free space in traditional public school buildings. However, during his 2013 campaign for mayor, Bill de Blasio pledged to curtail the practice. In response, in April 2014 the New York State legislature began requiring the city to offer rental assistance to new charters that are denied space in public school buildings. This report examines the de Blasio administration’s record regarding colocations, the extent to which there is space available for charters in underutilized public school buildings, and what additional steps the city and state might take to find room for charters.

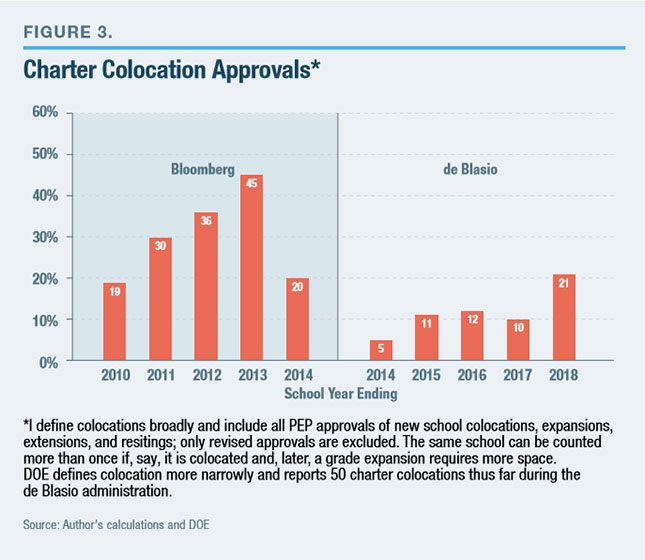

- Enrollment in New York City charter schools continues to increase. However, the colocation of new or expanded charter schools in public facilities has slowed dramatically: in the last five years of the Bloomberg administration, 150 charter colocations were approved, or 30 per year; in the first five years of the de Blasio administration, 59 colocations were approved, or about 12 per year.

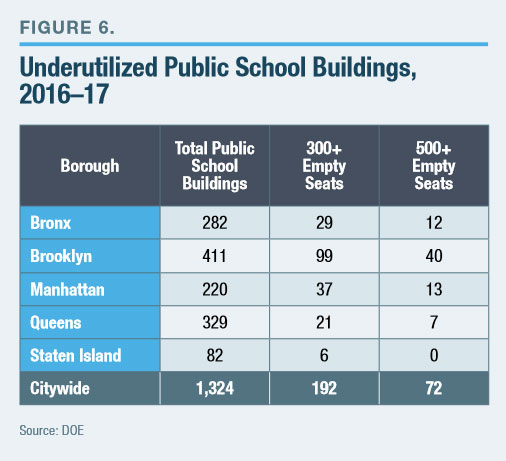

- More charters could be accommodated in underutilized public school buildings, especially in neighborhoods with many low-performing schools: in 2016–17, 192 buildings across the city had more than 300 empty classroom seats; 72 buildings had more than 500 empty seats.

- The cost of the lease-assistance program that helps charters to gain access to private space is growing rapidly: $51.9 million in fiscal year 2018 and likely rising to $62 million in fiscal year 2019.

______________________

Charles Sahm is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. Follow him on Twitter here.

Executive Summary

Charter schools have become an important part of the public education landscape in New York City. In the 2017–18 school year, there were 227 charters educating 114,000 students, about 10% of the city’s schoolchildren. The strong academic achievement of students in these schools, as well as parental demand, points to the need for more charter schools.[1] One big impediment is lack of space.

Former mayor Michael Bloomberg championed charter schools and accelerated their growth via colocation, the granting of free space in traditional public school buildings. However, during his 2013 campaign for mayor, Bill de Blasio pledged to curtail the practice. In response, in April 2014 the New York State legislature began requiring the city to offer rental assistance to new charters that are denied space in public school buildings.

This report examines the de Blasio administration’s record regarding colocations, the extent to which there is space available for charters in underutilized public school buildings, and what additional steps the city and state might take to find room for charters.

Introduction

Charter schools have become an important part of the public education landscape in New York City, where the first charters opened in 1999. In the 2017–18 school year, there were 227 charters serving 114,000 students, about 10% of all New York City schoolchildren.[2]

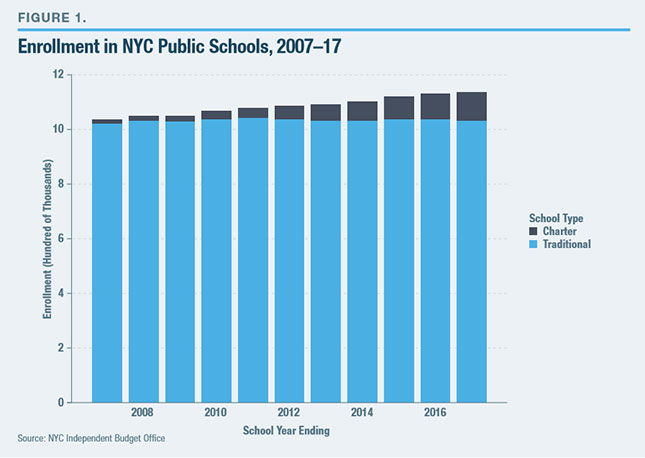

Total enrollment in New York City public schools is increasing, but enrollment in traditional (“district”) public schools is virtually unchanged from a decade ago (Figure 1). In the 2006–07 school year, district schools enrolled 1,042,078 students. In 2016–17, district schools enrolled 1,036,169 students. Charter school enrollment, however, has grown from 15,545 students in 2007 to 105,065 students in 2017.

Students attending charter schools achieve impressive academic results. On the 2017 state exams, they outperformed district schools by 14 percentage points in math proficiency and by 8 percentage points in English proficiency.[3] Low-income charter students outscored their district peers by 19 percentage points in math and by 12 percentage points in English.[4] Charters are an attractive option for many parents: last year, 73,000 students applied for 25,200 charter seats—leading to a wait list of 47,800 students.[5]

Students attending charter schools achieve impressive academic results. On the 2017 state exams, they outperformed district schools by 14 percentage points in math proficiency and by 8 percentage points in English proficiency.[3] Low-income charter students outscored their district peers by 19 percentage points in math and by 12 percentage points in English.[4] Charters are an attractive option for many parents: last year, 73,000 students applied for 25,200 charter seats—leading to a wait list of 47,800 students.[5]

Charter students’ academic achievement and parental demand both point to the need for more charter schools in New York City. Under the de Blasio administration, however, the practice of colocation, or the granting of free space to public charter schools in public school buildings, has been curtailed.

Public schools have been colocated with other public schools for as long as the city school system has existed. A 1905 book about the history of New York City schools notes that, in 1898, the year the five boroughs merged, “[i]n many cases, two or even three district school organizations or departments, each having its own principal, [are] in one building.”[6] Colocating new district schools within existing buildings was a hallmark of innovative community school districts in the 1980s and 1990s. Under the Bloomberg administration, this blossomed into a citywide effort: the system supported the expansion of new, small district schools as well as charters, in an effort to offer more viable school choices to families and to make optimal use of building resources.

Today, more than 1,100 of the city’s 1,800 public schools—or more than two-thirds—share space inside public school buildings that are often quite large.[7] Each school is assigned a segment of classrooms and hallways, while major amenities such as gyms and libraries are shared. Of these 1,100+ colocated schools, only 117 are charters.[8]

In April 2014, the New York State legislature passed a law stipulating that if the city does not provide new and expanding charters adequate space in a public school building, it must at least provide lease assistance so that charters can rent private building space. In 2017–18, 63 charters have been approved for lease assistance.[9] The cost to the city is now over $50 million per year, and finding and financing adequate private facilities in New York’s complicated and expensive real-estate market remains a challenge.[10]

Charter Access to Public Facilities Has Declined

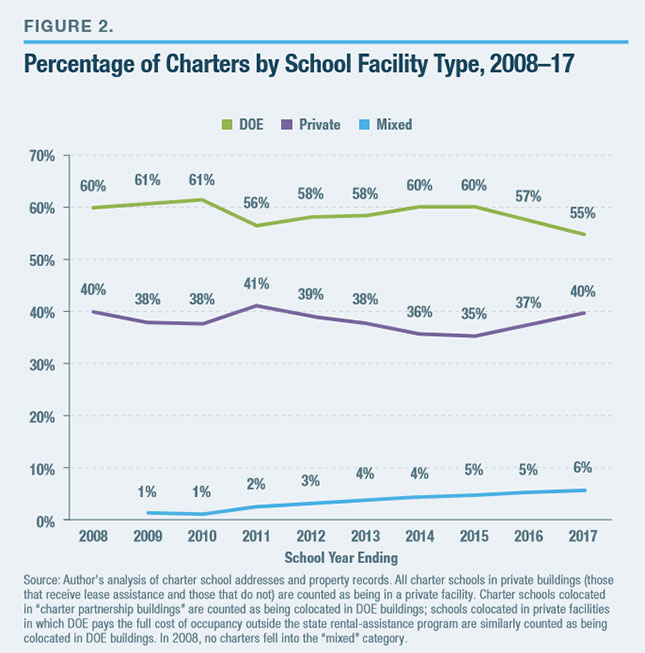

According to the New York City Charter School Center, of the city’s 227 charters, 117 are currently in buildings owned or leased by the New York City Department of Education (DOE); 90 are in private (non-DOE) space; and 20 have some students in DOE space and some in private space.[11] As Figure 2 illustrates, the percentage of charters housed exclusively in DOE space has declined over the past three years, from 60% to 55%; the percentage of charters in exclusively private space has risen, from 35% to 40%; and the percentage of charters using private and DOE space has risen from 5% to 6%.

According to the New York City Charter School Center, of the city’s 227 charters, 117 are currently in buildings owned or leased by the New York City Department of Education (DOE); 90 are in private (non-DOE) space; and 20 have some students in DOE space and some in private space.[11] As Figure 2 illustrates, the percentage of charters housed exclusively in DOE space has declined over the past three years, from 60% to 55%; the percentage of charters in exclusively private space has risen, from 35% to 40%; and the percentage of charters using private and DOE space has risen from 5% to 6%.

One reason the Bloomberg administration was able to find room for charters in public school buildings is that it closed more than 150 low-performing schools.[12] The de Blasio administration has been more hesitant to close struggling schools, preferring instead to attempt school turnarounds by investing resources via the city’s Renewal School program. The city did announce in December 2017 that it planned to close or merge 19 schools (14 in the Renewal School program) because of poor performance or low enrollment.[13]

One reason the Bloomberg administration was able to find room for charters in public school buildings is that it closed more than 150 low-performing schools.[12] The de Blasio administration has been more hesitant to close struggling schools, preferring instead to attempt school turnarounds by investing resources via the city’s Renewal School program. The city did announce in December 2017 that it planned to close or merge 19 schools (14 in the Renewal School program) because of poor performance or low enrollment.[13]

Before a charter can be colocated, DOE must produce an Education Impact Statement and an amendment to the Building Utilization Plan, both of which must be approved by the local Community Education Council and DOE’s Panel for Educational Policy (PEP).[14]

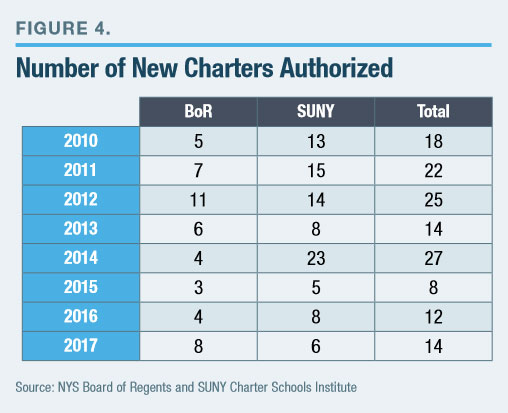

I analyzed all PEP approvals of charter school space requests from 2009–10 through 2017–18. As Figure 3 illustrates, the number of charter colocation space requests submitted and subsequently approved by PEP has declined during the de Blasio administration. In the last five years of the Bloomberg administration, 150 colocations were approved, an average of 30 per year. In the first five years of the de Blasio administration, 59 colocations were approved, an average of 12 per year. (The 2013–14 colocation tally is split between the Bloomberg and de Blasio administrations; see Appendix for all charter colocations under the latter.)

Most of the de Blasio administration’s 59 approved charter colocation requests have been grade expansions. Only 18 new charter schools have been provided colocated space in public school buildings. Four additional new schools approved for colocation received temporary space while private space is being built or found. One school received colocated space for a pre-K program. And one charter school received colocated space for grades K–8 after it had to vacate private space. Of the 14 new charters opening in 2018–19, 12 will do so in private buildings; an additional seven that received authorization to open in 2018–19 have had to delay their start because, among other reasons, they were unable to secure a suitable building.

When assessing whether to approve a charter colocation request, DOE gives priority to expanding existing charter schools, such as those that want to expand from, say, K–4 to K–8; to schools with proven track records; and to schools that might expand choice in a community by offering a different orientation, such as a single-sex charter, an arts-focused charter, or a charter targeting students with special needs.[15]

As discussed below, many of the most underutilized buildings in New York City are high schools. According to DOE, charters often decline space that is offered to them and sometimes even object to being placed in a building with a different charter school.[16] The Bloomberg administration would often colocate an elementary charter in a building with a high school, but the de Blasio administration refuses to do so for practical reasons (elementary and high schools are on different calendars, bathrooms need to be reconfigured, etc.) and for pedagogical reasons (it believes that it’s better to have students of similar grades in the same building).[17]

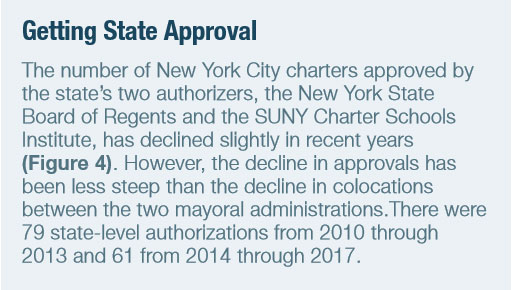

As noted, in 2014 New York State changed the process by which New York City charter schools are offered facilities. (Charters must also be authorized by state regulators; see sidebar “Getting State Approval”).

As noted, in 2014 New York State changed the process by which New York City charter schools are offered facilities. (Charters must also be authorized by state regulators; see sidebar “Getting State Approval”).

Charter schools that are newly opened or expanding grade levels must now first request colocated space from the city. If DOE does not have adequate space for the charter in a public school building (or a private building, at no cost), the charter is entitled to rental assistance. In July 2017, rental assistance for eligible charters was increased to a maximum of 30% of per-pupil funding, or $4,358 for 2017–18.

While fewer new charters are being authorized, many existing charters are growing, and requests to the city for more space for these schools continue apace. Since January 2014, the city has received 161 requests for space from new or expanding charter schools. It has denied 111 (69%) of these requests and approved 50 (31%).[18] Of the 111 schools denied space, 107 have gone through a successful appeals process and are eligible for lease assistance; of this group, 63 have had their leases approved and are currently receiving financial assistance or soon will receive it.[19] (Several more charters are in the process of having their leases approved; they will begin receiving support once they have students in their private buildings in 2018–19.) Because the city must formally deny a charter’s request for space before offering rental assistance, DOE agreed in 2017 to expedite the provision of rental assistance to charters that prefer it over colocation.

While fewer new charters are being authorized, many existing charters are growing, and requests to the city for more space for these schools continue apace. Since January 2014, the city has received 161 requests for space from new or expanding charter schools. It has denied 111 (69%) of these requests and approved 50 (31%).[18] Of the 111 schools denied space, 107 have gone through a successful appeals process and are eligible for lease assistance; of this group, 63 have had their leases approved and are currently receiving financial assistance or soon will receive it.[19] (Several more charters are in the process of having their leases approved; they will begin receiving support once they have students in their private buildings in 2018–19.) Because the city must formally deny a charter’s request for space before offering rental assistance, DOE agreed in 2017 to expedite the provision of rental assistance to charters that prefer it over colocation.

Is There Space for Charters in Public School Buildings?

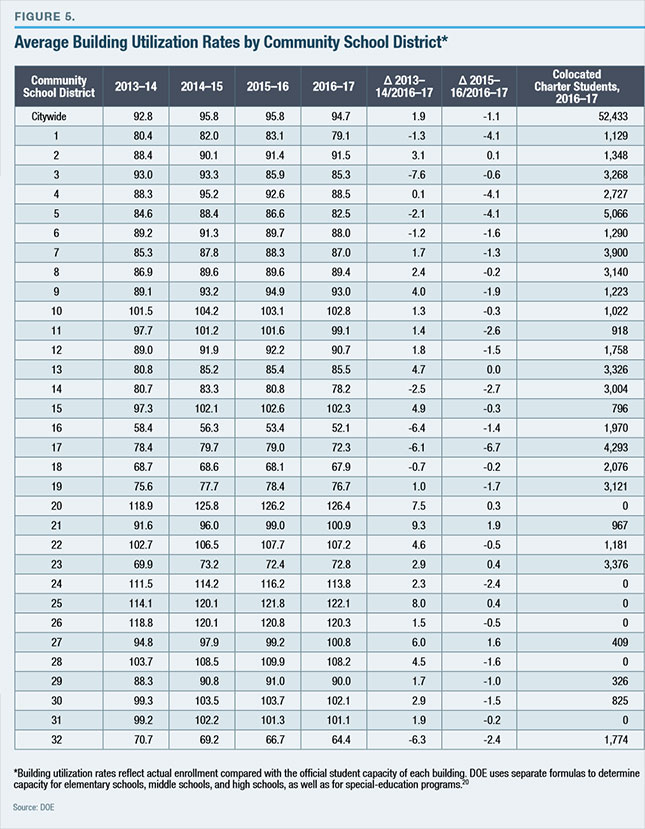

To answer this question, the author examined DOE’s annual Enrollment, Capacity & Utilization Report, commonly referred to as the Blue Book, which identifies the capacity of each DOE building, based on a set of uniform assumptions. (The most recent Blue Book covers 2016–17.) As Figure 5 indicates, average building utilization rates vary by community school district, though the districts with the greatest number of charter students in public school buildings have some of the lowest building utilization rates.

The citywide school building utilization rate has risen slightly, from 92.8% in 2013–14 to 94.7% in 2016–17. In 2016–17, the average building utilization rate for community school districts ranged from a low of 52.1% (i.e., roughly half of capacity—or very undercrowded) in community school district 16 (Bedford-Stuyvesant) to a high of 126.4% (i.e., roughly a quarter over capacity—or very overcrowded) in community school district 20 (Borough Park / Bay Ridge / Dyker Heights / Sunset Park). Twenty-five of the city’s 32 community school districts saw building utilization rates decrease between 2015–16 and 2016–17. Nine community school districts saw building utilization rates decline between 2013–14 and 2016–17.

One argument that has been offered for limiting the growth of charter schools is that charters cause overcrowding in public school buildings. But Blue Book data indicate that charters generally do not cause overcrowding in public school buildings.[21] Quite the opposite: in the nine community school districts with more than 3,000 charter school students in public school buildings, the average building utilization rate is 81.2%, compared with 94.7% citywide; of the 12 community school districts with building utilization rates exceeding 100%, half have no charter school students in public school buildings.

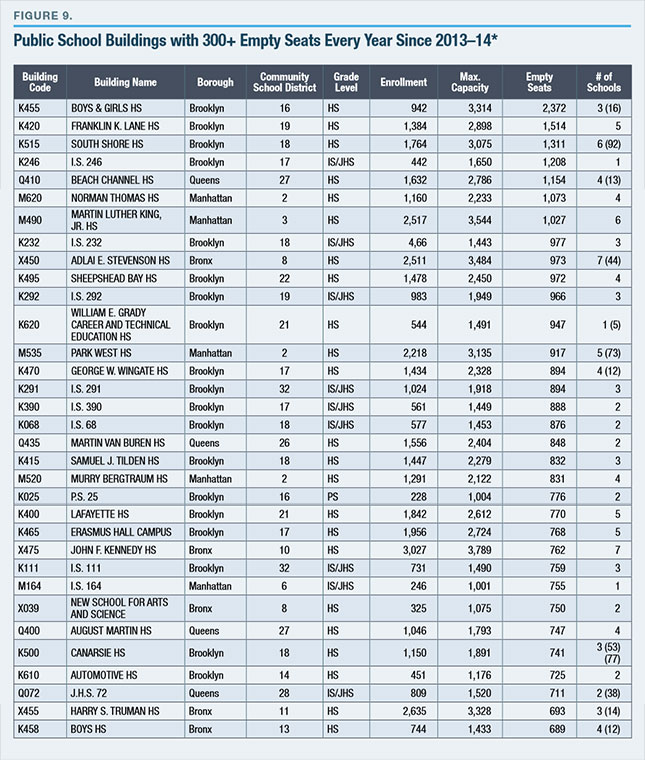

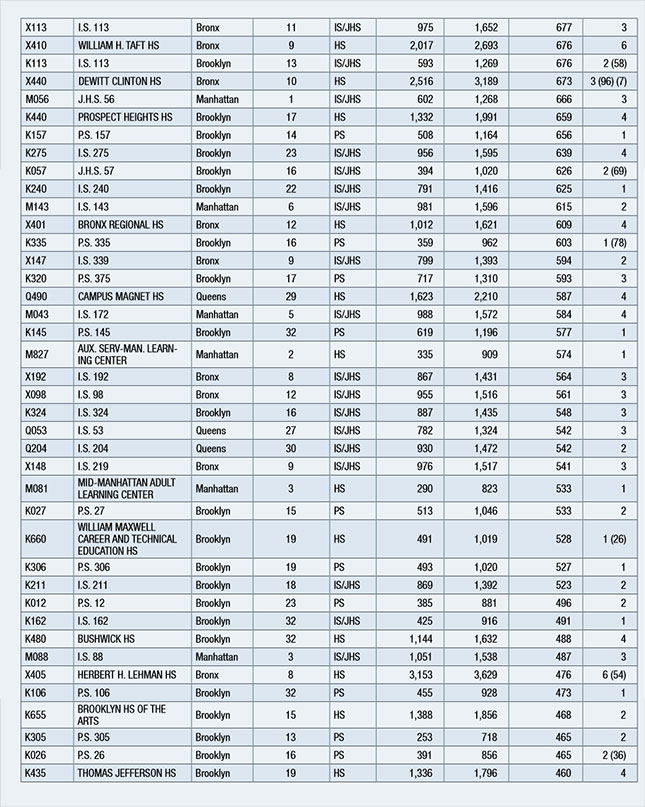

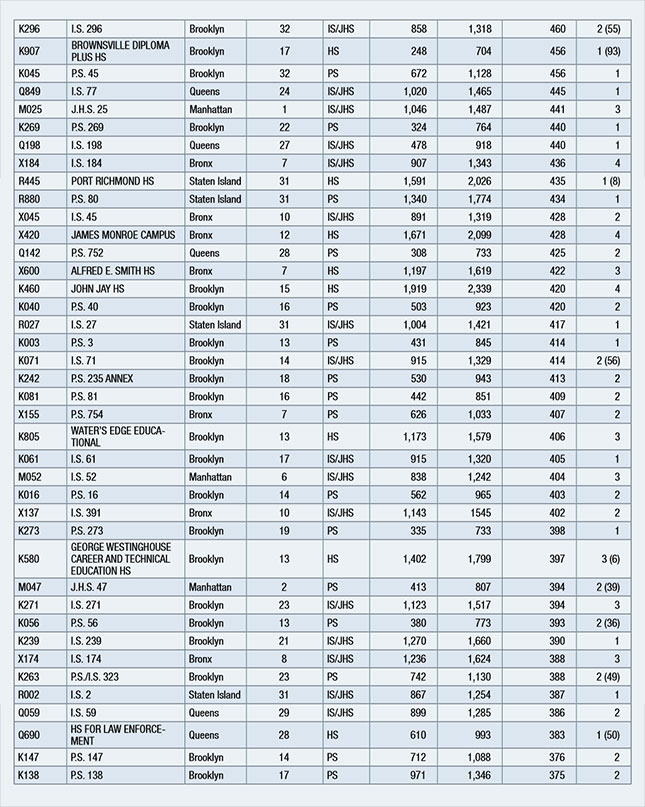

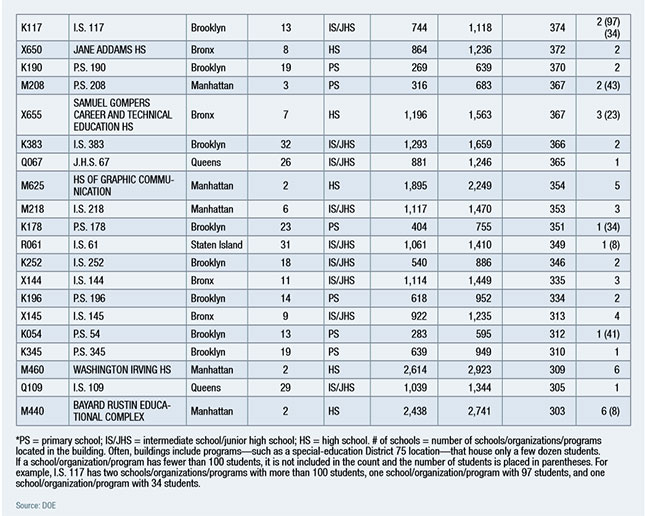

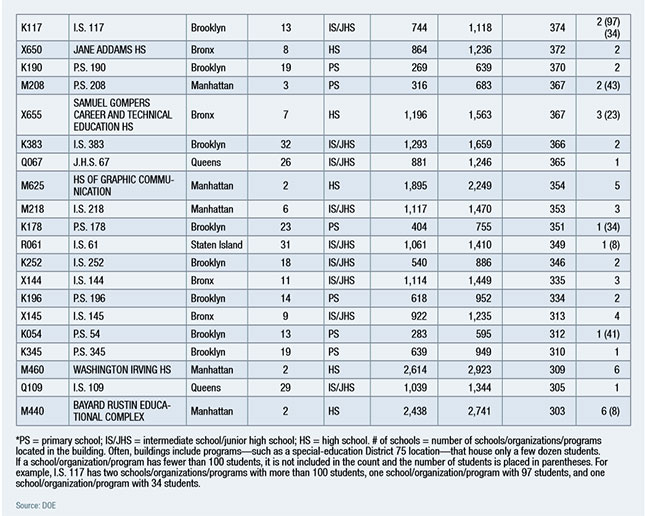

In 2016–17, 192 school buildings across the city had more than 300 empty classroom seats—the city-defined threshold that a building is underutilized and potentially has space to colocate (Figure 6). Of these buildings, 72 had more than 500 empty seats.

Why are so many buildings left idle when charter schools are being turned down for colocation space? According to DOE, some of these buildings are in neighborhoods where the student population is expanding, requiring space to be left aside to accommodate future growth; in other cases, the city has alternative plans for the unoccupied space. Still, 133 public school buildings in New York City have had more than 300 empty seats every year since 2013–14 (see Appendix); and 63 of these buildings have had more than 500 empty seats every year since 2013–14.

Why are so many buildings left idle when charter schools are being turned down for colocation space? According to DOE, some of these buildings are in neighborhoods where the student population is expanding, requiring space to be left aside to accommodate future growth; in other cases, the city has alternative plans for the unoccupied space. Still, 133 public school buildings in New York City have had more than 300 empty seats every year since 2013–14 (see Appendix); and 63 of these buildings have had more than 500 empty seats every year since 2013–14.

To be sure, the bare numbers aren’t the whole story. Without physically surveying all 133 buildings, it is impossible to say with certainty whether they can all accommodate additional schools. The Blue Book provides only a year-old snapshot of a building’s utilization, but some of the 133 buildings include schools that are being phased in or are expanding; some of the 133 buildings already contain several schools/programs, so adding another might not be appropriate; 48 of the 133 buildings are classified by DOE as “high school– level” buildings, which restricts their use to other high schools.

To be sure, the bare numbers aren’t the whole story. Without physically surveying all 133 buildings, it is impossible to say with certainty whether they can all accommodate additional schools. The Blue Book provides only a year-old snapshot of a building’s utilization, but some of the 133 buildings include schools that are being phased in or are expanding; some of the 133 buildings already contain several schools/programs, so adding another might not be appropriate; 48 of the 133 buildings are classified by DOE as “high school– level” buildings, which restricts their use to other high schools.

Nevertheless, even if high school–level buildings and buildings that already house four or more schools/ programs are excluded from the tally, there are still 81 buildings that have had at least 300 empty seats for the past three years (see sidebar “Room for More”). In these buildings, the number of empty seats ranges from 310 to 1,208.

Where Are Charters Requesting Space?

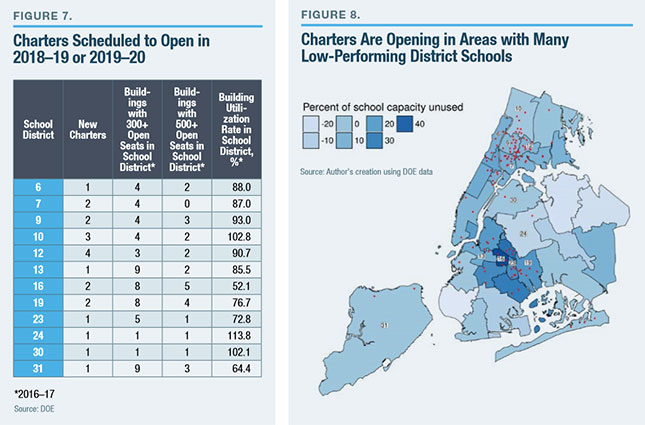

New York City’s public school buildings have space for more charters. But not all charters may wish to locate in the areas where these buildings are situated. Unfortunately, there is no public information on outstanding charter requests for space in public school buildings. We do know, however, that 21 new charter schools have been authorized to open in 2018–19 or 2019–20 (Figure 7 and Appendix). In the districts where these new charters will open, 60 public school buildings have had at least 300 empty seats for the past three years, and 26 buildings have had at least 500 empty seats for the past three years.

New York City’s public school buildings have space for more charters. But not all charters may wish to locate in the areas where these buildings are situated. Unfortunately, there is no public information on outstanding charter requests for space in public school buildings. We do know, however, that 21 new charter schools have been authorized to open in 2018–19 or 2019–20 (Figure 7 and Appendix). In the districts where these new charters will open, 60 public school buildings have had at least 300 empty seats for the past three years, and 26 buildings have had at least 500 empty seats for the past three years.

Figure 7 suggests that there is significant overlap between the neighborhoods where charters wish to locate and the neighborhoods that have space available in public school buildings. Figure 8 shows that there is also significant overlap between school districts with many low-performing schools and the school districts where new charters will open during the next two years: the numbered districts indicate those where new charters will open; and the red dots indicate elementary and middle schools where less than 15% of students scored proficient on the 2017 New York State math and English language arts exams, as well as high schools with graduation rates below 60%.[22]

Over the past three years, the number of charters receiving rental assistance to access private building space has nearly tripled, from 22 in 2014–15 to 63 in 2017–18. The cost to city taxpayers is growing fast, too: $51.9 million in fiscal year 2018 and likely rising to $62 million in fiscal year 2019.[23] For charters, rental assistance is no cure-all, either: finding and financing adequate private facilities in New York’s complicated and expensive real-estate market can be challenging even with the subsidy.

Over the past three years, the number of charters receiving rental assistance to access private building space has nearly tripled, from 22 in 2014–15 to 63 in 2017–18. The cost to city taxpayers is growing fast, too: $51.9 million in fiscal year 2018 and likely rising to $62 million in fiscal year 2019.[23] For charters, rental assistance is no cure-all, either: finding and financing adequate private facilities in New York’s complicated and expensive real-estate market can be challenging even with the subsidy.

Conclusion

Some of New York City’s community school districts—notably, those with struggling schools where many charters wish to open—enjoy substantial amounts of underutilized space. There are at least three reasons that charters should be offered such space. First, they are public schools. Second, they improve life outcomes for tens of thousands of students, many from poor families, who would otherwise be trapped in low-performing traditional public schools. Third, New York City would benefit financially from doing so: it pays nearly $52 million per year for charters to access private space, and that cost could easily double over the next few years if the city continues to reject a high percentage of charter colocation requests.

Recommendations

- Include charters in school facilities planning and funding. Total enrollment in New York City schools is increasing, but enrollment in district schools is flat and charter enrollment is growing. Charter space requests should be treated equitably, and charters should be viewed as part of the overall facilities picture, not separate from it.

- Create public policies that take advantage of unique private/public solutions. The city should consider reinstating Bloomberg-era policies such as the Charter Partnership Program, which used innovative public/private financing to build new schools.

- Close more low-performing schools, and use some of the space to open more charters. The Bloomberg administration closed more than 150 low-performing schools, which opened up space for new schools (district and charter). The de Blasio administration has closed only a handful of low-performing schools, preferring to invest more than $500 million in its Renewal School program, which has shown limited success.[24]

- Reconsider the policy of not colocating elementary schools with high schools. The de Blasio administration has declared that it will not colocate elementary schools with high schools, and it is often reluctant to colocate middle schools with high schools. But eight of the 10 most underutilized school buildings in New York City are high school– level buildings. Across the city, many buildings with appropriate modifications—schools located on different floors, separate entrances/exits, etc.— successfully colocate elementary schools and high schools. The city’s many underutilized high school buildings should be offered as potential sites for charters—and the city’s charters should not dismiss them out of hand.

- Survey non-DOE, city-owned buildings and determine whether any properties might provide viable sites for charter schools. During the Bloomberg administration, the city looked to nonschool properties it held (such as adult learning centers) as potential sites for charter schools. In addition, two charter schools (Promise Academy and DREAM) were built on New York City Housing Authority property, via innovative private/ public financing programs.

- Survey state-owned land and buildings to determine whether any properties might be viable sites for charter schools. For example, the 13-story Shirley Chisholm State Office Building at 55 Hanson Place in downtown Brooklyn is underutilized, according to state officials, and the state has considered putting the building up for sale.25 The state could offer the building to the city, with the stipulation that part of it be used for charter school facilities.

- Continue to examine former Catholic school buildings as potential sites for charter schools. More than 100 Catholic schools have closed in New York City since 2000. Many have been converted to charter schools. In fact, early in the de Blasio administration, the city found room for three Success Academy charter schools by leasing closed Catholic school buildings in Harlem, Washington Heights, and Rosedale (Queens). The city should consider purchasing former Catholic schools to house district as well as charter schools, too.

- Communicate and coordinate better with the charter sector. The city should be more transparent about its selection criteria for making colocation decisions. It should also proactively solicit information from charters about their growth plans—and, perhaps, incentivize charters to open, or expand, in areas with struggling district schools.

Appendix

Endnotes

- New York City Charter School Center, “NYC Charter School Facts.”

- Ibid.

- New York City Charter School Center, “Achievement in NYC Charter Schools.”

- Ibid.

- “NYC Charter School Facts.”

- Archie Emerson Palmer, The New York Public School (New York: Macmillan, 1905), p. 284.

- New York City Charter School Center, “Access to Space: Co-Location & Rental Assistance.”

- Ibid.

- Author’s correspondence with DOE.

- New York City Fiscal 2018 Budget. See p. 433 of FY18 Adopted Budget Supporting Schedules. The 2014 legislation included a provision for the state to reimburse the city for some of the cost of this program once the annual cost surpassed $40 million. That level has been reached, and the city will be reimbursed for 60% of the amount over $40 million one year after the costs are incurred. This shifts some of the burden from the city’s budget to the state’s budget, but taxpayers will still bear the cost.

- “Access to Space: Co-Location & Rental Assistance.”

- New York City Independent Budget Office, “Phased Out: As the City Closed Low-Performing Schools How Did Their Students Fare?” January 2016.

- Patrick Wall, “New York City Plans to Close, Shrink, or Merge These 19 Schools into Other Schools,” Chalkbeat, Dec. 18, 2017. One school was subsequently removed from the closure list, while the city’s Panel for Educational Policy denied two other school closure requests and delayed a third; all four of these schools were in the city’s Renewal School program.

- A handful of stand-alone, non-colocated charters in public school buildings do not need to go through the PEP approval process.

- Author’s correspondence with DOE.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See DOE, “Enrollment, Capacity & Utilization Report,” December 2017.

- See, e.g., Rose Dsouza, “Parents Contest Charter Schools Proposed for Crowded District 2,” Chalkbeat, May 2, 2012.

- We do not include District 75 special-education schools or transfer high schools designed for students who have dropped out or have fallen behind in credits.

- See New York City Council, “Fiscal Year 2018 Budget”; and New York City Council, “Fiscal Year 2019 Budget.”

- See, e.g., Marcus A. Winters, “Costly Progress: De Blasio’s Renewal School Program,” Manhattan Institute, July 18, 2017.

- Erin Durkin, “State May Sell Off Office building at 55 Hanson Place in Fort Greene,” New York Daily News, Jan. 31, 2012.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).