The Dodd-Frank law, intended to fix the problems that led to the financial crisis, has only made things worse.

In mid-April, President Trump called Dodd-Frank, the 2010 financial-regulation law, "horrendous," and said he would work to fix it. The House Financial Services Committee, too, wants big changes, as indicated by the 600-page replacement bill it unveiled this week. The biggest problem with Dodd-Frank is that it doesn't work. New evidence shows that on a few key measures, the law hasn't put new market pressure on large banks, and that it's also failed to protect consumers.

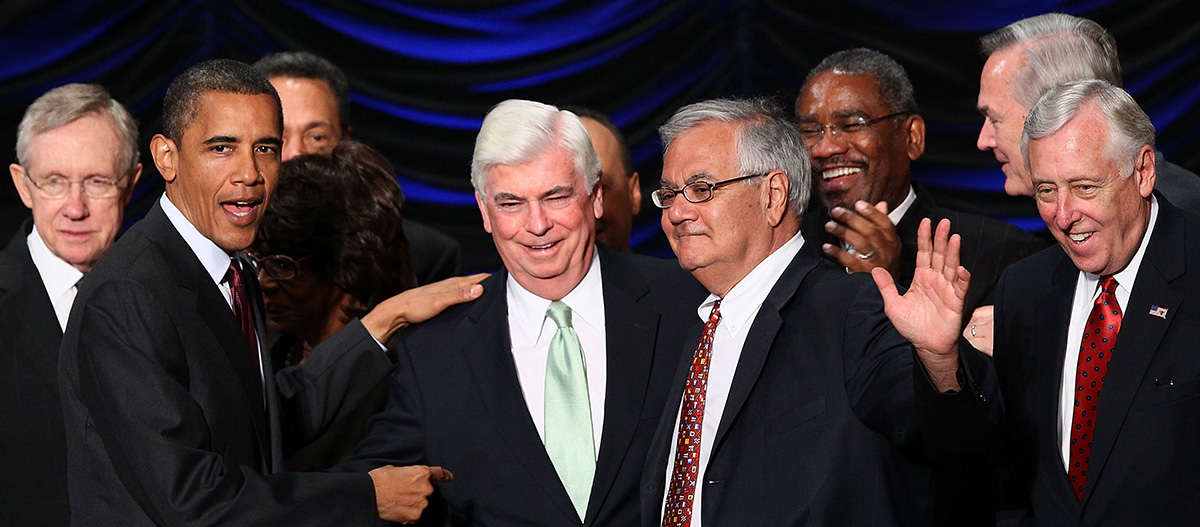

Dodd-Frank was one of only two major laws passed during the Obama era (the other was the Affordable Care Act). Regulators imposed new rules on everything from leverage — how much a financial firm can borrow — to debit-card fees.

With more than half a decade having passed since the former president signed the law, the Manhattan Institute invited Columbia Business School professor Charles Calomiris to convene academic scholars to consider the early empirical results. A summary of their work was published this week.

Dodd-Frank hasn't yet been tested by a full economic cycle, including a recession and high interest rates. It's impossible, then, to know whether the law succeeds or fails in several critical aspects, including ending too-big-to-fail. But the early evidence presents cause for concern.

First, Dodd-Frank may be harming growth. In one forthcoming research paper research paper, Christa H.S. Bouwman, Shuting (Sophia) Hu, and Shane A. Johnson of Texas A&M University's Mays Business School find that Dodd-Frank may be reducing credit for corporate borrowers.

How? Under Dodd-Frank, banks with more than $10 billion in assets face additional regulatory requirements, and banks with more than $50 billion incur an even higher regulatory burden. Banks just below each threshold are taking actions to ensure that they remain below the relevant threshold, the authors find. Such banks are growing their assets more slowly than larger banks.

These banks are also charging borrowers higher interest rates for corporate loans, according to the researchers' analysis of borrowing rates over the past 15 years.

Dodd-Frank "created costs" in terms of higher regulatory requirements for large banks that smaller banks "attempt to avoid by altering their growth and pricing behavior," the scholars conclude. Large banks have not changed their behavior.

The authors theorize that banks below each threshold charge more to borrowers to make up for the prospect that such lending will bring them over the threshold, thus forcing them to incur higher regulatory costs.

They theorize, alternatively, that small banks are making riskier loans, thus demanding higher interest rates, or that small banks may serve markets in which borrowers do not have a competitive choice.

Whichever conclusion is correct, the implications are not good for growth. Under one conclusion, small businesses are less able to borrow because of a constraint unrelated to their credit risk. Their available lenders do not wish to grow bigger and bear the cost of more onerous regulations. The small businesses, then, are at a disadvantage to larger competitors, as larger companies can borrow in global bond markets.

Under another conclusion, small banks must make riskier loans, distorting economic activity, perhaps because their larger competitors dominate the market for less risky loans.

Second, Dodd-Frank may be harming competition. In a second paper, Bouwman, Johnson and Shradha Bindal, also of the Mays school, analyze data over the past 15 years to assess whether banks are making fewer acquisitions in order to stay beneath the $50 billion threshold that would trigger the greatest level of regulatory scrutiny under Dodd-Frank. The authors conclude that such banks are indeed "less likely to engage in acquisitions."

However, much smaller banks — those below the $10 billion threshold — are more likely to enter into such purchases or mergers. The authors theorize that for the smaller banks, the benefit of growth may outweigh the additional regulatory costs; for larger banks, growing above $50 billion triggers regulatory scrutiny that is not worth the cost.

The conclusion raises concerns that Dodd-Frank has created a protected class of existing financial firms with assets above $50 billion, as smaller firms now have a reason not to reach that size. Dodd-Frank did nothing to break up America's largest banks. But it may also discourage new competition for the megabanks that existed before Dodd-Frank.

Third, Dodd-Frank may have shifted consumer costs rather than reducing them. To protect bank-account holders, Dodd-Frank capped the fees that banks with over $10 billion in assets can charge retailers and other merchants for customers' debit-card use. This cap theoretically reduces costs for customers by reducing retailers' own costs.

The provision may not be working as lawmakers planned, though. In a third forthcoming paper, Benjamin S. Kay of the Treasury's Office of Financial Research and Mark D. Manuszak and Cindy M. Vojtech of the Federal Reserve Board note that, before Dodd-Frank, fees averaged 44 cents on an average $38 transaction.

The law capped such fees at about 24 cents for the same transaction: 21—22 cents as a flat fee, then .05% of the transaction value. This cap resulted in a big loss for the banks that the researchers studied: 28% of their $14.6 billion in such revenue in 2010, or $4.1 billion.

But, the authors find, the banks subsequently offset 90% of this loss — by charging customers higher bank-account fees. Banks increased deposit fees by 15%. This hike "offset effectively all of the lost interchange income at treated banks," the researchers noted.

The final result didn't help bank-account holders, then. But it also points to a deeper problem: again, the lack of competition among large banks. The authors concluded that "large banks have substantial market power over their retail customers."

A successful financial-reform law would have reduced the disadvantages that smaller businesses face in borrowing and increased competition among large, medium-size and small banks. More competition, in turn, would have been good for consumers. Dodd-Frank, nearly seven years in, hasn't accomplished these goals.

This piece originally appeared in Investor's Business Daily

______________________

Nicole Gelinas is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and contributing editor at City Journal. Follow her on Twitter here. This piece is based on her recent report, Reforming Obama-Era Financial Regulation.

This piece originally appeared in Investor's Business Daily