The GOP should embrace bipartisan health care efforts, but Obamacare's individual mandate has got to go.

The Congressional Budget Office recently estimated that the repeal of the individual mandate would be responsible for 15 million of the projected 19 million person increase in the uninsured by 2020 under the Better Care Reconciliation Act proposed by the Senate GOP. But coverage under current law is close to the levels that CBO predicted would prevail without the mandate, and the fine used to enforce it has proven ineffective and inequitable in making healthy individuals lacking employer-sponsored insurance bear the costs of subsidizing those with pre-existing conditions.

“The individual mandate is not the only way to prevent people from waiting to get sick before purchasing health insurance coverage. ”

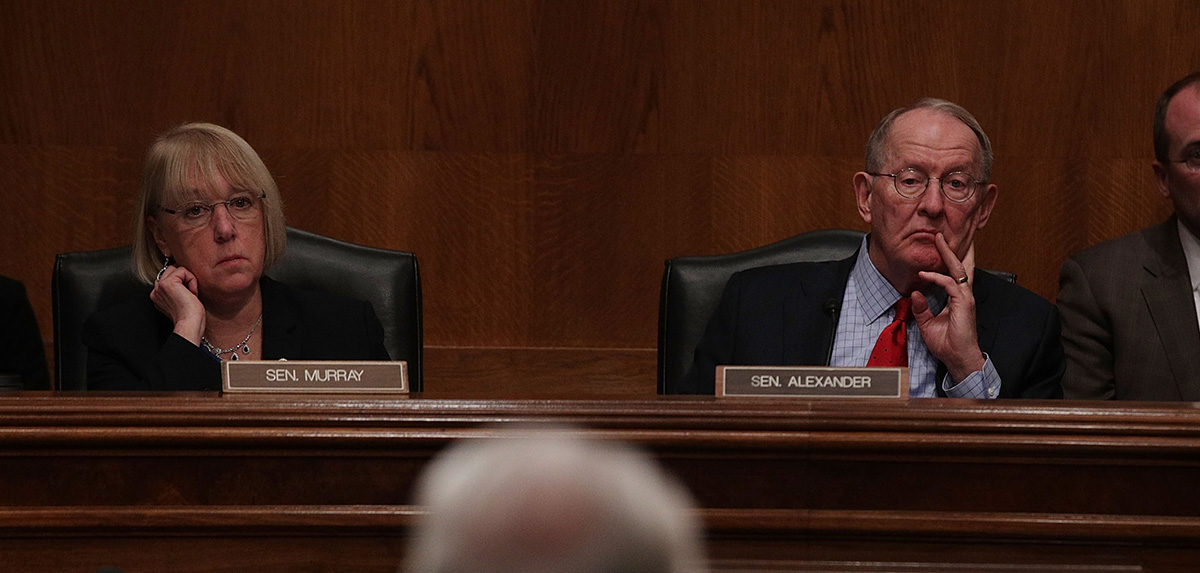

Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, recently announced his intention to pursue a bipartisan approach to stabilizing the nongroup market for health insurance. Republicans should support these efforts but insist upon the repeal of the individual mandate and the deregulation of plans purchased off the exchange in return for the provision of full cost-sharing and market-stabilization subsidies.

For seven years, and through four election cycles, Republicans pledged to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare. But, while the GOP unified around opposing Obamacare, Republicans disagreed about which parts of the bill should be eliminated. Some quietly approved of the Medicaid expansion, others liked the exchange subsidy structure and many liked regulatory protections for individuals with pre-existing conditions. But one provision of Obamacare has always united Republicans: All hated the individual mandate.

The "individual shared responsibility payment" requires those who choose not to purchase "minimal essential" health insurance coverage to pay a fine of up to the average cost of the cheapest permitted exchange plan type ($2,676 for individuals in 2016). Such a "bronze" plan, which covers only 60 percent of an individual's health care costs, offers appalling value relative to the $709 median health care expenditures incurred by those who are enrolled neither in Medicare or Medicaid.

This penalty is unsurprisingly the least popular part of Obamacare, and Barack Obama himself opposed it while running for president in 2008, arguing, "If a mandate was the solution, we could try that to solve homelessness by mandating everybody buy a house." Hillary Clinton had supported the mandate in 2008, believing it necessary to support insurers required to enroll individuals with pre-existing conditions on the same terms as healthy individuals, to prevent everyone from waiting until they're sick before signing up for health insurance.

But the individual mandate is not the only way to prevent people from waiting to get sick before purchasing health insurance coverage. Policymakers could allow individuals to opt out of regulatory guarantees for pre-existing conditions or impose waiting periods for those who fail to maintain continuous coverage. Nor is the mandate necessary to maintain the Affordable Care Act's system of subsidies to provide a safety net for low-income individuals and those with pre-existing conditions. Those subsidies automatically expand to keep health care costs limited as a share of an individual's income. It is only necessary if one wishes to impose uniformity of coverage by herding healthier individuals into highly regulated plans, which offer them terrible value for money.

In office, Obama reversed his position after the CBO estimated that the absence of an individual mandate would leave 28 million individuals uninsured. But, in fact, 28 million was exactly how many people remained uninsured with the mandate in 2015.

In the absence of the individual mandate, at least the 6.5 million uninsured who preferred to pay a fine and go without coverage than to purchase an exchange plan would have more freedom to make insurance arrangements at a cost closer in proportion to their likely health care utilization needs. Also, most of the 8 million, whom CBO predicts would choose not to enroll in Medicaid and employer-sponsored coverage, would still retain the right to do so on the same terms if not forced to enroll.

A reasonable case was made that proposed reductions in subsidies for the exchanges in the recent Senate GOP bill, combined with the deregulation of off-exchange plans proposed by Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, would have caused the exchanges to collapse through lack of revenue. But this would not be the case if the mandate were repealed and fully competitive plans permitted off-exchange in return for the provision of market stabilization and cost-sharing reduction subsidies to the exchanges.

With only 2 percent of those above the income cut-off for exchange subsidies currently purchasing plans, the repeal of the mandate would make much less difference to its risk pool than many people think. Indeed, the small group which has been willing to pay full price for exchange plans would likely have been disproportionately expensive to cover.

Republicans can therefore demand the repeal of the individual mandate and liberalization of off-exchange plans as the price of voting for bipartisan legislation to provide further subsidies and cost-sharing reduction payments to exchange plans. In attempting to do so, they can be assisted by the Trump administration, which has broad discretion to waive enforcement of the mandate and the ability to make available more affordable alternatives.

It is understandable that insurers would prefer a situation in which the government mandates the purchase of their products and prohibits cheaper alternatives, but that's no way to foster a competitive marketplace that functions well in the interests of consumers.

This piece originally appeared in U.S. News & World Report

_____________________

Chris Pope is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. Follow him on Twitter here.

This piece originally appeared in U.S. News and World Report