America's welfare state has come under a new line of attack in recent years. This critique, particularly common on the progressive left, contends that social-services managers and staff provide too much support to the working poor and other, relatively better-off cohorts by focusing on their most promising clients while avoiding the hardest cases. "Creaming," or "cream-skimming," as the practice is sometimes called, is viewed as a major cause of why so many difficult cases continue to go unaddressed despite massive social-welfare spending, compounding the welfare state's reputation for incompetence and leaving the neediest Americans behind.

In fact, for some on the left, creaming is in a sense the distinctive problem with social services in America. When moderate cases are served in an entirely different and separate manner from the hardest cases, progressives suspect that this inequality is rooted in service providers' desire to have an easier job or to improve their outcome metrics. It is therefore imperative, in their view, that governments take measures to ensure a more equitable distribution of the most difficult cases among service providers.

Creaming should be seen not as the result of poor policy design, inadequate oversight, or corruption, but as a distinctive feature of a well-designed social-services system. It can be justified on the basis of both needs and capacity.

Social services meet social needs, and many social needs — such as those of the working poor — are serious enough to merit government intervention. The claim that the moderately needy are easier to help than those most in need is simply not true. Society often has higher expectations for the moderately needy than for the neediest among us, and therefore the former often require just as much time and effort on the part of service providers as the latter.

Creaming is also necessary from a capacity standpoint. Maximizing talent among service providers should be a major concern in any social-welfare program, but especially for those programs that provide disadvantaged Americans with rehabilitative, educational, and therapeutic services, as opposed to simply redistributing resources. Granting service providers some measure of independence will make working in the field more attractive, and meaningful independence will entail giving them some degree of authority to distinguish among the needs of different clients and decide whom to help.

While progressive opponents of creaming see themselves as the principled ones in this debate, in truth, it's unprincipled to demand that the same school serve both disruptive students and promising students, as if the latter existed only for the benefit of the former. Similarly, it's unprincipled to house homeless men committed to work and sobriety in a shelter populated by others who do not share those values.

As progressives continue to dissent from the bipartisan consensus on welfare reform and work requirements, creaming has increasingly come under fire. But before policymakers rush to alter America's social programs, they should ask themselves: Would these reforms result in a fairer and more effective system? If the answer is no, they should countenance creaming.

UNEQUAL BY DESIGN

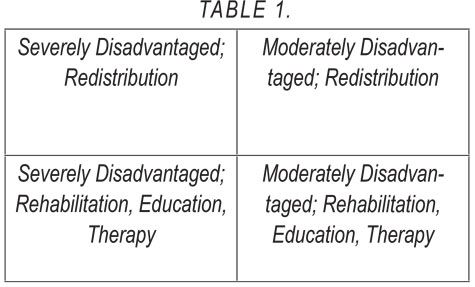

Social-services programs in America spend billions annually to assist disadvantaged populations. In 2019, the year before the pandemic hit, the federal budget devoted about $360 billion to safety-net programs (excluding Social Security benefits and health insurance) for low- and moderate-income individuals and families. These programs assist both severely disadvantaged and moderately disadvantaged Americans. Some redistribute wealth, while others provide rehabilitative, educational, or therapeutic services. Table 1 breaks down the four possible combinations of these features.

Some programs fit neatly into one of the four boxes. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Medicaid, for example, belong in the top-left corner, while the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) would appear in the top-right corner. The creaming debate pertains mainly to programs that straddle the divide between the bottom two boxes and provide services at the state and local levels. Examples of such programs include public schools in low-income communities, community-based mental-health programs, homeless shelters, substance-abuse services, workforce-development efforts, and re-entry programs for prisoners.

Why are these the programs most frequently accused of creaming? In his 1980 work Street-Level Bureaucracy, public-administration scholar Michael Lipsky likened creaming by government agencies to battlefield triage. Government workers in non-redistributive programs, he argued, are tempted to cream as a way to cope with inadequate resources:

Confronted with more clients than can readily be accommodated street-level bureaucrats often choose (or skim off the top) those who seem most likely to succeed in terms of bureaucratic success criteria. This will happen despite formal requirements to provide clients with equal chances for service, and even in the face of policies designed to favor clients with relatively poor probabilities of success.

Critics of creaming claim that an adequately funded social-services system would not require more severely needy clients to compete with moderately needy clients for caseworkers' time and effort. More generous public outlays, they insist, would rectify this problem.

Creaming is also said to be a harmful offshoot of poorly designed performance-evaluation systems. Toward the end of the 20th century, there was a major push to improve results in government programs by contracting with non-profit organizations. Although the welfare state exists partly out of a sense of duty, we also care how well its various parts succeed at improving lives. To that end, governments often coupled their contracting arrangements with an enhanced focus on performance evaluation.

Measuring performance is especially critical for programs that offer rehabilitative, educational, and therapeutic services — the types of services most susceptible to creaming — for one reason: They're expensive. Running a school or job-training program entails more overhead than simply cutting checks, as redistributionist progressives are fond of pointing out. Reducing failure rates is thus a key part of ensuring that the money invested in these programs is being well spent.

To creaming opponents, this coordination between government and non-profits has not resulted in better performance, but only more deception. They argue that, because social-services staff know their performance is being monitored and evaluated, they cream in order to make their results appear more successful than they really are. Jerry Muller, a professor at the Catholic University of America, begins his 2018 book The Tyranny of Metrics with a story about a fictional surgeon who boosts his outcome measures by working only with low-risk patients — an analogy he claims is emblematic of social programs' response to performance evaluation. "Gaming through creaming," he argues, is rife in the modern age of metrics.

Both the triage and "gaming through creaming" criticisms overlook some crucial aspects of the practice and its role in social services. To see how creaming can be beneficial, we should begin by acknowledging that it's hard to improve broken lives, and many programs that try to do so fail. Given this difficulty, combined with the fact that no program has unlimited resources, it's understandable that service providers would prioritize cases with the best chance of success.

Secondly, progressive critics of creaming have a misguided view of how social programs should operate. The contemporary left prizes equality and social integration above all else, and any programs that violate these values are deemed automatically unjust. What these critics fail to consider is that the principle of justice-as-equality might not be the best lodestar for a successful social-services program. Indeed, this was a key lesson of the 1990s.

Justice-as-inequality tends to be associated with undemocratic regimes, but it was a driving motivation behind welfare reform. In his 1992 book Rethinking Social Policy, Christopher Jencks illustrated how, under the old Aid to Families with Dependent Children program (replaced by TANF in the 1996 welfare-reform law), a single mother employed full time who earned minimum wage — he referred to her as "Sharon" — could well wind up barely better off than an unemployed single mother "Phyllis." Jencks presents this scenario in his analysis of Charles Murray's influential 1984 work Losing Ground, which featured a fictional unwed couple named Harold and Phyllis.

Even if nobody quit work to go on welfare, a system that provided indolent Phyllis with as much money as diligent Sharon would be universally viewed as unjust. To say that such a system does not increase indolence — or doesn't increase it much — is beside the point. A criminal justice system that frequently convicts the innocent and acquits the guilty may deter crime as effectively as a system that yields just results, but that does not make it morally or politically acceptable. We care about justice independent of its effects on behavior.

Out of these considerations emerged the notion of "making work pay" through policies like a much-expanded EITC. The goal was not just to reduce poverty, but to craft a more just welfare state, and thus one with a stronger claim to legitimacy.

Yet as mentioned above, the welfare-reform consensus of the '90s has begun to fray in recent years. Dependence on entitlements other than cash assistance has expanded widely, and support for extending work requirements has declined. Many leading progressives — such as Princeton's Matthew Desmond, author of the 2016 book Evicted — believe more redistribution is essential to addressing struggles faced by lower-class Americans said to be left behind by the "make work pay," or "employment-based safety net," approach. Meanwhile, economic populists on the right have called for a mix of family-oriented redistribution schemes and reforms to the broader economy to help the working class.

In a political environment where welfare reform is viewed with skepticism or hostility and solutions to old and new social challenges are being debated, it's critical not to lose sight of Jencks's point about the value of programs designed with the moderately disadvantaged in mind. To use an example from the drug-overdose crisis, harm-reduction measures — like providing access to methadone and clean needles — can be life-saving for long-term opioid addicts. But for younger people less far down the road of chronic addiction, harm reduction could exacerbate their disorder before they give abstinence-oriented programs a fair shot.

To get a better sense of why creaming can be an effective approach, it's worth taking a closer look at social services in two key rehabilitative, educational, and therapeutic fields: education and housing.

EDUCATION AND TALENT

Charter schools are one of the most successful legacies of the "re-inventing government" era of the 1990s. These government-funded schools are authorized by a public agency to operate independently of their community's central district administration. Enrollment is lottery-based for schools with an excess of applicants for available seats, and they disproportionately serve black and Latino students.

Across the thousands of charter schools that exist, quality varies. But as Thomas Sowell discusses in his 2020 book Charter Schools and Their Enemies, the model has allowed New York City and other urban areas to develop schools that not only outperform district schools with broadly similar student demographics, but also, in some cases, outperform district schools in wealthy suburbs. More revealing than charters' claim to excellence is their popularity: They enroll more than 3 million students nationwide. It's doubtful that urban public education would be punctuated with as many models of excellence as it is now had the district-school paradigm remained absolutely dominant, as it was in the 1980s. And yet charter schools are a prominent target on the left.

Charter-school skeptics attribute the success of charters to creaming: It's not that they're better schools than the district schools; it's that charter schools serve better students. Charters allegedly filter students through both the front door, by drawing children from families motivated enough to enter the lottery, and the back door, by counseling out troublesome or poorly performing students. A leading critic along these lines is education historian Diane Ravitch. Teachers' unions, which object to non-unionized charters receiving funds that would previously have flowed to central districts, have also leveled creaming charges at charter schools.

Charters are unlikely to be shut down completely because of this blowback; they're too popular for that. But they could face increased regulations or other pressures to reform. For instance, schools of all kinds have come under intense scrutiny due to their disciplinary policies, which are said to have a disparate impact on minority students. Leading charter-school networks such as the Knowledge Is Power Program and Uncommon Schools have already signaled that they intend to relax their standards in light of this criticism. The more regulations and public pressures charter schools face, the more they will resemble district schools, thus undermining their purpose.

In his 2019 book How the Other Half Learns, Robert Pondiscio provides a thoughtful response to creaming charges against charter schools. He analyzes Success Academy, the notable New York City-based charter-management organization, based on a year spent closely observing one of its schools in the South Bronx. Pondiscio, who previously taught in a South Bronx public school, takes creaming accusations more seriously than Sowell and other charter proponents. But he responds with a defense based on families and fairness.

Success Academy students hail from the most troubled neighborhoods in New York City. They are overwhelmingly minority and low-income, but not the lowest-income. They also come from the more stable families in those neighborhoods. Students' parents tend to be married — a rarity in their communities but essential to the Success Academy approach, which places enormous demands on parents' time — as well as churchgoing and employed. What left-leaning media outlets have found abhorrent about the Success Academy approach — such as its propensity to suspend compulsively disruptive elementary-school kids — these parents see as a big draw, especially relative to the chaotic district schools their children would normally attend.

What does society owe to such parents? Pondiscio argues that to deprive them of an option like Success Academy would be profoundly unfair. Ordinary district schools tend to neglect their strivers — those students who consistently behave, pay attention, and complete their homework. Too often, strivers in impoverished communities achieve less in life because they are not pushed to excel: Their teachers are chiefly preoccupied with managing their more troublesome peers. Placing strivers in schools and classroom environments where teachers can focus on their needs, Pondiscio says, will better enable them to reach their full potential.

Indeed, a poor minority student who performs at proficient levels in reading and math while in middle school is well on track to graduate high school on time and attend a four-year state university. But, as Pondiscio illustrates, the appropriate supports could set that same student on track for the Ivy League, whose member colleges are desperate to identify promising students from poor urban neighborhoods. It would be hard, expensive work for school systems to devote themselves to converting as many proficient students to above proficient as possible while also catering to the needs of less-proficient students. But if charter schools were to cream the more proficient students from the population, ordinary district schools would be able to focus on bringing the less-proficient students up to par, while the charters could focus on turning the community's strivers into future Ivy League graduates.

Would that system be less fair than one that defines success in terms of elevating the below-proficient to proficiency levels? Critics of creaming might say so. But government programs should be judged, at least in part, by whom they betray. Success Academy families may live in crime-ridden neighborhoods and make low wages, but they embody the values essential to upward mobility — and in the face of considerable social pressure to abandon those values. Policies that sacrifice their children's potential out of some well-meaning but misplaced devotion to equity betray these families.

Charter-school critics may respond by arguing that these promising students could benefit their academically struggling peers by being kept in the same classrooms with them. But that scenario eerily resembles minority neighborhoods prior to desegregation. After segregation was lifted, many upwardly mobile minority families moved to the suburbs. Several chroniclers of modern life in the neighborhoods they left behind have noted the deleterious effects that such "black flight" had on social capital in those areas: Nicholas Lehmann in his two-part 1986 Atlantic series "The Origins of the Underclass," William Julius Wilson in his 1987 book The Truly Disadvantaged, David Simon and Edward Burns in their 1998 book The Corner, Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh in his 2006 work Off the Books. But who among us would seriously consider re-imposing racial segregation to strip those families of their freedom to move, even though some of the more disadvantaged members of poor, minority neighborhoods might conceivably benefit from their presence? Upwardly mobile schoolchildren have their own needs, and thus their own claims on government — which should be met by schools designed especially with them in mind.

One last area where creaming is relevant to charters is employment. Attracting high-quality people to run charter schools is crucial to their success, and the best charter schools tend to be located in big cities, where talent is more abundant but competition is also plentiful. Social services can't rely on compensation to attract and retain talent the way corporate America can, so if we want to draw the most capable people into the education sector, we need to grant them the freedom to choose which populations to work with. This will likely entail allowing them to cream, as ambitious social entrepreneurs want to make their mark by participating in and starting up programs that change lives. At the same time, their sense of pride may also guard against creaming, for the best social entrepreneurs seek to tackle the most stubborn challenges. The important thing is not whether they engage in creaming; it's that they have the freedom to choose to do so.

SERVICES FOR THE HOMELESS

In recent decades, homelessness policy has increasingly embraced the idea that a service system's quality depends on the depth of its commitment to its least-functional clients. "Priority: Home!" — the Clinton administration's strategic plan on homelessness — featured the following epigraph, attributed to the president:

I do not believe we can repair the basic fabric of society until people who are willing to work have work. Work organizes life. It gives structure and discipline to life. It gives a role model to children. We cannot repair the American community and restore the American family until we provide the structure, the value, the discipline and reward that work gives.

Yet since the 1990s, standards for success in services for the homeless have shifted markedly downward. Near the turn of the century, scholar-advocates like the University of Pennsylvania's Dennis Culhane began arguing that homeless-services systems had to focus more on the needs of the "chronically homeless" — those with both a long-term experience of homelessness and a disability — in order to be more successful. The goal of housing as many chronically homeless individuals as possible, and for as long as possible, gained crucial salience during the following decades. In the last 15 years, the nation's stock of permanent supportive housing — which offers subsidized shelter with few or no strings attached — has grown by over 75% (+163,000 units). Meanwhile, the stock of transitional housing — which offers time-limited shelter, often accompanied by expectations to participate in services and pass drug tests — has declined by close to 60% (-130,000 units).

While "low-barrier" shelter and other "housing-first"-style models — including San Francisco's Navigation Center program and New York City's Safe Haven program — have proliferated in recent years, old-school shelter and housing providers who believe in a "workfare" approach to homelessness have either seen their funding cut or have been unable to expand. The Trump administration attempted to grant these programs more freedom to experiment with sobriety and work requirements, but advocates for the homeless objected, arguing that such measures would be counterproductive. Instead, they persuaded Congress to maintain restrictions on the use of barriers for the initial and continual receipt of housing benefits.

There is an undoubted humaneness to redoubling efforts to prevent the chronically homeless from falling through the cracks. But in practice, not much will be expected of a chronically homeless individual, and when that case becomes paradigmatic, not much will be expected of services for the homeless in general; a program that achieves housing stability for 50 clients will earn greater acclaim than one that moves 20 clients into self-sufficiency.

Advocates for the homeless strenuously dispute the notion that "housing first" means "housing only"; they characterize housing as a "platform" required for people to overcome drug addiction and secure gainful employment. But housing programs for the homeless have been extensively studied — through efforts like the 2015-2016 Family Options Study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the 2018 report on permanent supportive housing by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, to name just two examples — and the research shows that the platform metaphor is inaccurate, as these programs don't produce any impressive social or economic outcomes for their participants. Subsidized housing can house people, but on its own, it can't further the more substantive goals of social policy.

At bottom, it's fundamentally unfair to provide equal treatment to people on whom we place different expectations. Take two single homeless men, both of whom have rocky pasts, but one of whom is determined to reach as far up into the working class as he can. Toward this end, he puts up with substandard living conditions and participates in every class and program available to him. Years before succumbing to drug addiction and homelessness, he made working-class wages; now that he's on his way back up, he's willing to take entry-level jobs below his dignity. He is determined to do whatever it takes to succeed.

The second man does none of these things. He spends his days nursing grievances about what he considers mistreatment by shelter providers, the failure of the government to provide him with permanent housing, and the corrupt capitalist system that denied him a job appropriate to his abilities. He is truculent and shiftless. He refuses to change his ways.

Both of these men need and deserve government assistance. But if the system fails both — meaning if neither manages to make headway back into the working class — clearly it's more disgraceful that it failed the first man. To try to minimize such systemic failure, a homeless-services system cannot be organized strictly around the principle of justice-as-equality; it must be allowed to target its most promising recipients.

IN DEFENSE OF CREAMING

Creaming, at its best, means designing programs that take less serious needs seriously by parsing them from the needs of the most disadvantaged individuals. Allowing programs to cream with a good, or at least a better, conscience would advance the cause of honesty in public debate and protect effective programs from well-intentioned but harmful reform efforts.

Creaming can facilitate social integration, properly understood. Charters that cream at the school level prevent social disintegration at the neighborhood level. Homeless-services providers who cream allow their clients to be better integrated into the broader non-homeless community, if less well integrated into the street-encampment community. Healthy forms of social integration build social capital, which is often key to socio-economic success. In that regard, the most valuable function of a re-entry program for prisoners may be less the skills and credentials participants gain (such as a GED or a commercial driver's license) than the bonds developed through a shared sense of overcoming adversity. Government-funded non-profits can strengthen the fabric of civil society just as much as privately funded programs and organizations can, though doing so may not be a goal specified in their formal contract.

More tolerance for creaming would allow for a certain "market segmentation," in the phrase of public-administration scholar E. S. Savas, to develop in the social services. Instead of having to scale up programs to spread public resources among both the moderately and the seriously needy, creaming can enable the most promising candidates to escape the social-welfare system entirely, thus freeing up funds for programs targeted toward the truly disadvantaged. To be sure, this would increase the risk of creating a government that helps many people who could help themselves. But it would also reduce the risk of leaving the moderately disadvantaged out in the cold.

While it would be too much to say that confusion about creaming explains "how we got Trump," there's a certain parallel between doubts about creaming's legitimacy and doubts about the health of the American working class. What are government's specific responsibilities to those on the verge of the underclass, the moderately disadvantaged? Like health-care systems, the welfare state must provide care and treatment. The excellence of a health-care system hinges more on its ability to heal those who would benefit from treatment than its ability to care for those who are unlikely to fully recover. By the same token, a social-services system that judges success based on how well it directs maximum resources to as many poor people as possible would be perfectly at home in a socialist country. How well the American system serves moderately needy people — how rarely it lets them down — defines it as a truly American social-services system.

______________________

Stephen Eide is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and contributing editor of City Journal.

This piece originally appeared in National Affairs