How to Fight Housing Price Inflation Policy Menus for Stopping Government-Induced Housing Woes from Spreading Beyond the Coasts

Introduction

Where we live affects where we work, how we raise our families, who our friends and neighbors are, and how prosperous we and our children prove to be. But the choice of where to live is constrained by local governments through land-use rules, permitting, and the discretionary review of housing development. As a result, much of American life is downstream of local housing policy.

High home prices and rapidly rising rents are no longer solely coastal problems: they are spreading across America. While short-term price trends can fluctuate, America’s long-term housing shortage is a large and growing problem. This brief will explain how local regulations are causing rapidly inflating home prices in once-affordable places. It will then provide state lawmakers with a tool kit of facts, arguments, and policy solutions to America’s housing crisis.

Reforming America’s local housing regulations to stop housing inflation is pro-family, pro-worker, and pro–property rights. In order to help policymakers achieve this needed reform, what follows is a menu of policy reforms aimed at restoring property rights by cutting red tape, making housing pay off, and streamlining local governments.

The Home Price Inflation Crisis

America’s homes have never been more expensive than they are today.[1] Owner-occupied and rental housing costs are continuing to rise. This means that fewer Americans are able to own their slice of the American dream. Rising interest rates and supply-chain shortages following the pandemic of Covid-19 hardly help. Today’s hot housing market may be ending as the Federal Reserve attempts to dampen inflation, but our decades-long housing crisis remains.

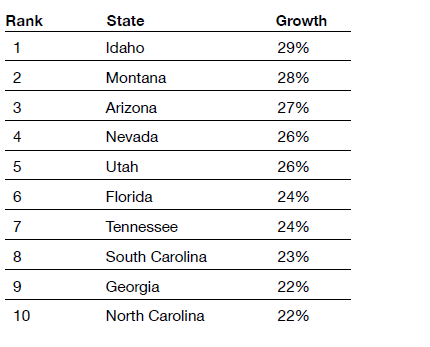

Home prices have risen by 44% in the past two years, amid 40-year-high inflation rates.[2] The median sale price for new and existing homes is now well north of a record-high $400,000.[3] Monthly mortgage payments nationwide were 60% higher in September 2022 than a year ago, thanks to higher interest rates, even as inflation-adjusted household income was falling. Of the 100 top housing markets in America, 67 saw record-high home price appreciation this past year, while the other 33 saw prices still rising by at least 9%.[4] The hottest markets for owner-occupied and rental homes are nearly all in the South and Mountain West.[5]

Metro Home Price Growth, May 2021–May 2022[6]

State Home Price Growth, 2021[7]

Barely half of homes currently on the market are affordable to a family making the national median income.[8] For a first-time buyer who wants to purchase a median-priced home, the standard 7% down payment came to $27,400 in April 2022, which requires a level of savings that rules out more than 90% of today’s renters.[9] All of this presents a challenge for America’s 25–34-year-olds—millennials—who are reaching peak home-buying and family formation at this very moment.

Worse, starter homes no longer exist as a functional category for home builders and, increasingly, buyers, as well. In 1980, 40% of homes being built were entry-level homes (smaller than 1,400 square feet); by 2019, this figure had fallen to just 7%.[10] The largest decreases in starter home production were concentrated in the South, with Florida seeing the largest decrease in starter home production. In 2020, when 2.38 million Americans bought their first home, only 65,000 entry-level homes were built, compared with 418,000 in the late 1970s.[11]

States with the Largest Decreases in Starter Home Construction[12]

And there’s no refuge for those who can’t afford to buy a home: rents are up nearly 25%, or roughly $400 per month, since June 2019.[13] In the most recent full year of 2021, Phoenix (26%), Austin (24%), and Las Vegas (24%) saw the largest increases among large cities, while smaller cities such as Naples and Sarasota (both in Florida) saw even higher hikes (42% and 37%, respectively).[14] Going into 2022, a separate analysis from the CoStar Group found that asking rents were still up by 8.4% year-on-year in July, and that eight of the top 10 rent growth markets were in the Sunbelt.[15] Roughly half of all renter households are rent-burdened, spending more than 30% of their income on housing, a key measure of affordability, and a quarter are severely rent-burdened, by spending half their incomes on rent.[16] Since 2015, real rents have risen the most in the lowest-income areas of the country. Rising rents ultimately lead to rising home prices.[17]

Coastal superstar cities used to be the worst offenders when it came to high housing prices. Since 1980, New Yorkers have seen their average house prices rise about 700%; and in San Francisco, by more than 900%.[18] These cities, along with pricey hubs such as Boston, Los Angeles, and San Jose, have for decades topped the lists of the most expensive housing markets in the country.[19] High housing costs in these cities harm economic growth, worker productivity, and personal opportunity for Americans both within and well beyond their borders.[20] Elite cities and their states have failed to keep housing affordable and accessible to hardworking Americans.

But America’s housing crunch is spreading.[21] Simply look at Austin, Texas, where an otherwise unremarkable two-story, 2,500-square-foot home 20 miles north of downtown was listed for sale at $370,000 on December 30, 2020.[22] Within minutes, buyers lining up to view the house formed traffic jams on its quiet suburban street. By the New Year’s deadline, there were 96 offers. The final sale price: $541,000—46% above asking price, to an out-of-state buyer from California. By May 2022, Zillow estimated that this home would sell for upward of $800,000—or more than double its original listing price.[23]

Given local incomes, the priciest places in America outside California and New York are now cities like Austin and Miami.[24] The fastest-growing home prices during the Covid-19 pandemic were in such places as Boise, Phoenix, and Salt Lake City.[25] Nashville, Tennessee, topped the nation during this period for the fastest-selling homes in the nation.[26] Home value growth in 2021 exceeded the median salaries in nearly every major Southern and Mountain West metro in America.[27] And today, inflation is most intensely felt in Sunbelt cities like Phoenix, Miami, and Tampa—outpacing the national rate of 8.5% in July 2022—mostly due to rising rents brought on by increasing migration.[28]

Southern and Mountain West states, as well as many small to midsize cities, have boomed over the past few years as many Americans searched for lower cost of living and a better quality of life. The Covid-era shift toward more remote work may have played a major role in pushing up home prices in areas where lifestyles and housing costs were more amenable than in coastal cities, such as San Francisco.[29] This trend is likely to continue as flexible work arrangements remain popular, millennials begin and raise families, and the ranks of retirees rise.

America’s housing cost crisis is not a universal experience; low demand and low incomes have kept home prices low throughout much of America’s Rust Belt, while large surpluses of land in the Plains or in places far removed from job centers are similarly insulated from crisis.[30] As a share of income, housing costs in the Sun Belt are still lower than those on the coasts. But the home price trajectories in Sunbelt hubs like Las Vegas and Austin are arguably similar to those in Los Angeles or San Diego, just a few decades behind. Americans living in a growing state with in-demand cities are going to face a housing crisis sooner or later—and for many, that moment is now.[31]

Why does this country face a housing crisis? The simple, Econ-101 explanation is there is more demand for housing than supply. Recent studies have estimated that America’s housing shortage ranges from 2 million to 5.5 million homes, given historical building and household formation trends.[32] (The consensus is that we need to find space for roughly 4 million households.)[33] But we are building far fewer homes than at any time since the Great Depression,[34] opting instead to make do with an ever-decaying housing stock in the meantime.

This shortage shows up in America’s now-historically low vacancy rate, leaving fewer places to live. Both homeowner and rental vacancy rates are nearing all-time lows.[35] America’s long-term housing shortage was most recently exacerbated by a Covid-era boom in demand driven by record-low interest rates and a sudden burst in household formation. As families and jobs grow, we have failed to keep up. The long-term and growing shortfall in homes in this country has enormous implications for the quality of life of American families, the health of the labor market, and the future of our communities.

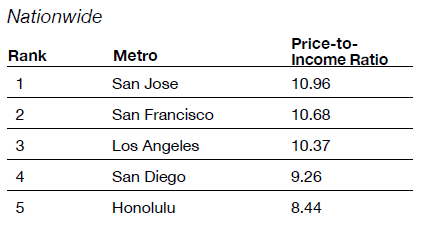

We also face a housing crisis because home prices are fast outpacing incomes. Median home values rose three times faster than median household incomes between 1970 and 2010.[36] Looking even further back, and accounting for inflation, while real home prices have risen by 118% since 1965, real incomes have grown by only 15%.[37] The longtime rule of thumb for home affordability is that the price must be equivalent to 2.6 years of household income.[38] But California’s coastal cities, such as Los Angeles and in the Bay Area, now have price-to-income ratios of more than 10 years. The fastest growth in home prices relative to area incomes has been in America’s Sunbelt, whose price-to-income ratios are approaching those of its coastal peers. Indeed, accounting for rising mortgage interest rates, places like Tampa required a nearly 50% raise in income from 2021 to 2022 simply to still afford the median home there.[39]

Years of Median Family Income Needed to Afford the Median Home, 2021[40]

Years of Median Family Income Needed to Afford the Median Home, 2021

Change in Annual Income Needed to Afford the Median For-Sale Home, Given Rising Prices and Mortgage Rates, 2021–22[41]

The High Price of Regulation

The long-term reason for housing price inflation is government’s artificial restrictions. Overly restrictive local zoning regulations, labyrinthine and lengthy approval processes, and plans and institutions set up to say no—these are the fundamental causes of America’s housing shortage.

Burdensome restrictions delay or deny new housing altogether and prevent landowners from realizing the value on their property while mandating the type of housing that must be built and what amenities it must provide, regardless of what people want or need. Short-term home price trends can still vary by fluctuations in demand (e.g., changes in interest rates and household formation) and nonregulatory supply-side issues (the Covid-era supply-chain crisis).[42] Nevertheless, over the long term, local land-use restrictions and this “vetocracy” of red tape restrict housing supply and thus drive up the cost of housing. The government-induced housing shortage increases the cost of living for families, inhibits geographic mobility, stifles economic productivity, and burdens both renters and buyers. When we restrict how Americans can use their land, increased housing demand simply leads to higher prices rather than more homes.

Artificial restrictions on housing growth take several forms, including:

- Bans on housing types, such as through zoning or preservation schemes

- Mandates on lot size, density, parking, design, and more

- Discretionary review, which empowers politicians and bureaucrats to dictate terms on specific projects

- Urban growth boundaries, which aim at killing suburbs

- Building codes, which set standards for construction

The first three categories usually fall under the category of zoning, which dictates land use and densities and intersects with growth boundaries and building codes to tighten their control of what is built and where. Zoning is the most consistent—and, arguably, the greatest—barrier to Americans’ housing freedom. These rules regulate use and density over vast stretches of developable land in this country. There is often no binding comprehensive plan or coherence to oversee these rules in any given city, but only an ever-expanding scope of regulation.

The scope and spread of these rules and review are relatively new. Between 1950 and 1970, home prices rose roughly 2% per year as housing quality and construction costs rose. The expense of building the structure accounted for nearly all the cost of buying a home.[43] Starting in the late 1960s, though, land-use regulations became more restrictive and widespread in cities and suburbs alike. Newly required environmental reviews and public hearings were death by a thousand paper cuts for new development. The results were clear: rising real home prices starting around 1980 become completely detached from the relatively stagnant cost of construction, such that paying more was no assurance of getting more houses.[44]

Restrictions on building show up most clearly in land costs, which, just before the pandemic, accounted for 37% of the value of each existing residential property in this country, though easily accounting for two-thirds or more in close-in neighborhoods.[45] Put another way, we pay two to four times the cost of construction to buy a home outside the coasts today; this gap is a regulatory tax imposed by local government. As Harvard’s Edward Glaeser and his coauthors conclude, “This increase reflects the increasing difficulty of obtaining regulatory approval for building new homes.”[46]

Today’s Housing Policies Harm Everyday Americans.

They harm hardworking families and communities:

Skyrocketing home prices are a rising tax on hardworking families already pinched by rising inflation. Pricey housing can force people to wait to get married or have kids,[47] or to have fewer children than they planned on having, and it encourages them to move away from job centers to cheaper suburbs with longer commutes.[48] Many families simply live where they can afford, rather than where they want. If the share of homes near good schools can’t grow to accommodate demand, home prices rise instead, while the overall tax base fails to grow to help pay for more teachers and better facilities. Young graduates have a harder time staying close to family as prices rise, while empty-nester parents are stuck with homes whose size or place (or property-tax bill) is quite different from what they might otherwise desire as they age.

They harm workers in pursuit of the American dream:

The artificial housing shortage is a raw deal for workers. Since 2000, low-wage workers have earned less by moving to higher-opportunity places, after we take into account higher housing costs.[49] Even going to college pays less than it once did, with so much of the gain going to pay rent or mortgage costs. People who would have moved for a better life are instead stuck or move elsewhere, thus inverting the historical American norm of moving to opportunity. This, in turn, distorts the labor market, making it difficult for employers to hire, thus harming the country’s long-term growth.

They harm our property rights and freedom:

Local governments across America regularly and actively prevent homeowners from using their property as they’d like. Landowners often face endless red tape to make improvements or repairs on their property, let alone to build on it. Such regulations reduce the potential value of a property without any compensation. As a substitute for diluting individual property rights, local governments offer an informal, difficult-to-enforce collective property right, backed by state power, that allows homeowners to tell their neighbors what they should and should not do on their land.

Policy Menus

The aim for reform is for communities to have the freedom to flourish, for states to keep their promise of opportunity for hardworking families, and for property owners to have the right to live where and how they’d like. Housing reform does not destroy communities; it builds them up. The proof is that when we let states compete, the pro-growth, pro–property rights states win.

States should lead the way. Local governments are creatures of their states, and their land-use authority takes place within an institutional and legal framework established and regularly revised by the state. A healthy localism depends on the accountability that only a state can provide. Furthermore, restrictive local land-use decisions have a regional and often statewide impact as rising home prices spread. States whose leadership favors freer markets should be at the forefront leading housing reforms.[50]

Every other policy tool in the housing menu entrenches our housing crisis or is little more than a Band-Aid covering a gaping wound. Policies like inclusionary zoning, which mandates or incentivizes a portion of new housing to be affordable to varying degrees, depends on high rents to sustain the subsidy while taking more units off the market.[51] Government-produced housing rarely has sufficient rents to sustain maintenance, leading to decay—a problem that also befalls cities subject to rent control—and has never been able to keep up with demand. All too often, affordable housing for the few maintains unaffordable housing for everyone else.

States can tackle America’s housing crisis through three policy menus:

1. Restoring property rights

- Homeowner’s bill of rights

- Housing appeals board

- Permit shot clock

- Ensure that local plans are local law

2. Making housing pay off

- Outcome-based housing awards

- Allow housing to pay dividends

- Down-payment savings program

3. Streamlining local government

- Legalize starter homes

- Simplify building and design rules

- Ban housing bans

- Sandbox for housing innovation

These reforms may be taken piecemeal—even small gains and wins can make a big impact down the road—but each menu of reforms is designed for its parts to work best together. For instance, the property-rights menu ensures that homeowners have defined property rights, localities have their own enforceable plans, petitioners of government have a right to a speedy reply, and the housing appeals board backstops all these protections.

Those charged with passing these reforms should take pains to:

- Frame the debate as one about housing inflation rather than a referendum on the reform itself

- Focus messaging on the benefits of reform to families, workers, and property owners that appeal to the interests of voters rather than, say, esoteric discussions of supply and demand

- Avoid narrowly tailored revisions that invite end runs around the reform’s intent

- Stress the noncontroversial natures of reform, in order to avoid inviting negative partisanship

- Ensure that a single state point person or agency close to the governor has ownership of these reforms’ success.

Menu #1: Restoring Property Rights by Cutting Red Tape

POLICY: Homeowner’s Bill of Rights

States should enshrine and strengthen their citizens’ property rights in state law by enacting the following principles, primarily in the state zoning enabling act:[52]

1. Zoning actions should not arbitrarily or capriciously deprive a person of the legitimate use of his or her property, including its subdivision.

2. Zoning regulations must be shown by the enacting body to be necessary to achieve a vital and pressing governmental interest—that is, for the regulation and provision of public goods and infrastructure, such as transportation, sanitation, water, and utilities.

3. Any land-use laws or actions that impose new limitations on the use of property and that result in reductions to the property’s fair market value entitle the owner to just compensation.

4. To condemn a property, officials must have clear and convincing evidence that it poses a direct threat to health or safety.

5. Property owners should have a reasonably expeditious way to challenge undue regulations or delays related to their property.

Models

- Arizona’s Private Property Rights Protection Act, approved by a substantial margin of voters in 2006, limited the government’s ability to seize land through eminent domain or overregulation, by requiring that it be done only for truly public purposes. It also required state and local governments to compensate landowners whenever land-use regulations that did not serve public health and safety goals diminished property values by reducing existing rights to “use, divide, sell, or possess private real property.”[53] (Landowners are responsible for demonstrating any decrease in property value.) This measure maintained local interests and did not directly change any existing regulations while still protecting and clarifying private property rights. Since its passage, the act has curtailed new land-use regulations in Arizona.[54]

- North Carolina’s Act to Increase Housing Opportunities empowered property owners by ensuring that “ambiguities … are to be construed in favor of the free use of land” as well as by clarifying that “local government shall not adopt or enforce an ordinance downzoning property that has access to public water or public sewer, unless the local government can show a change in circumstances that substantially affects the public health, safety, or welfare.”[55]

POLICY: Housing Appeals Board

Courts can be costly, slow, and lacking in expertise when considering whether land-use regulators overstepped their bounds. Indeed, the judicial appeals process can take several years, depending on the case and jurisdiction in question. In the meantime, neither side has much certainty of how the matter will be resolved.[56] Property owners and local governments deserve timely, certain, and expert review when it’s needed.

That is why states should establish a Housing Appeals Board (HAB) with the authority to review any discretionary local land-use decision.[57] HAB, comprising three to five governor-appointed subject-matter experts, would have the power to speedily review any abuses of local discretion that are not in accordance with state and local law and then to approve previously denied applications.

HAB offers a cheaper, faster route for review of land-use decisions while maintaining local authority and deference over land-use decisions. HAB would have authority to review any discretionary land-use decisions while maintaining deference to local governments. Specifically, this includes, but is not limited to:

- Planning-board decisions on subdivisions or site plans

- Decisions on variances, special exceptions, administrative appeals, and ordinance administration

- Growth management controls

- Decisions of historic district and conservation commissions

- Municipal permits and fees applicable to housing and housing developments

- Mixed-use and combinations of residential and nonresidential uses

- Inclusionary or subsidized housing

- Any other innovative land-use controls

If local governmental bodies or staff abuse their discretion or try to run around state or local law, HAB could intervene to approve formerly denied applications or allow projects to proceed. Courts already play this oversight role, in theory, but judicial review can be so costly and time-consuming so as to represent its own form of project denial. HAB, by contrast, would render decisions in weeks or months rather than years. It also offers subject-matter expert oversight and allows nonlawyer land-use experts (such as engineers, architects, and land surveyors) to represent appellants, who could be anyone from a developer to a homeowner trying to add a backyard apartment for grandkids.

Crucially, the creation of an HAB imposes no new limits on local government’s lawmaking abilities or discretionary land-use power. It cannot override zoning, building, or planning regulations. A statewide HAB instead acts as a safeguard to ensure that land-use decisions are made in accordance with preexisting state and local law.

Model

- New Hampshire’s SB 306, passed in 2019 as part of the state’s budget with bipartisan backing, established a Housing Appeals Board to “hear appeals of decisions of municipal boards, committees, and commissions regarding questions of housing and housing development.”[58] Filing fees are an affordable $250, and the board must make a ruling within 90 days.[59] (HAB decisions can be appealed to the state supreme court.) Modeled on the state’s Board of Tax and Land Appeals, the board consists of an attorney, a real-estate broker, and a professional engineer, and it operates on an annual budget of about $500,000.[60] As of August 2022, the New Hampshire HAB has issued 31 decisions and is generally vacating or remanding three decisions to every one that it upholds (nearly all of which involve rejected proposals).[61]

POLICY: Permit Shot Clock

Permit shot clocks are intended to make the development review process faster, standardized, and more transparent. Expedited and streamlined approval processes reduce costs to obtain development approval, which, in turn, helps lower overall development costs and ultimately makes it easier to build more housing.

The shot clock would give local governments 60 days to approve or deny any development-related application, or the permit is automatically granted. These decisions must be made in good faith and not denied merely as a negotiating tactic or to buy the relevant agency more time. Agencies must provide reasons for any denial, and applicants should be allowed to resubmit applications that respond to agency concerns, without any fees. Applicants approved with conditions are allowed to provide written responses and receive approval or a response from the relevant agency within 15 days of resubmission. Noncompliance by a jurisdiction with the permit shot clock must come with penalties, such as lowering their eligibility for state transportation funding.

Models

- Florida’s HB 1059, passed in 2021, requires cities and counties to process or request corrections within 30 days for any application to a build a new home.[62] If they fail to do so, 10% of the application fee is refunded for every business day past the deadline. For corrected applications, officials have 10 business days to approve or disapprove, with a late penalty of a 20% fee refund plus a further 10% penalty for each additional missed day, up to five days. Localities are required to post their permitting processes online as well as the status of applications. Thousands of new home permits are now being processed faster in Florida, resulting in a 30% jump in issued permits in 2021, compared with the previous year.[63] Penalties for delay are also proving quite real; one Florida resident was refunded 60% of a $6,600 permit application fee because of undue delays.

- Minnesota established the “60-day-rule” in 1995, requiring state and local “governmental entities” to approve or deny a written request for zoning, certain environmental reviews, or expansion of the urban service area within 60 days, or the request is approved.[64] (The rule does not cover building permits or subdivision regulation.) While agencies have the flexibility to extend the review period indefinitely for nearly any reason, courts have demanded strict compliance with the rule.[65]

POLICY: Ensure that Local Plans Are Local Law

Comprehensive plans are complex exercises in local self-government where the public, planners, and elected officials draft and adopt a vision for their community’s development. State zoning enabling acts consistently call for comprehensive plans and for land-use regulations that accord with these plans. Yet today, many of the long-term, community-developed recommendations contained in these local plans are not reflected in the local zoning code. Some jurisdictions do not have even have a plan to guide their land-use restrictions.[66]

State lawmakers should require any local government that adopts or enforces a zoning ordinance to prepare and adopt a binding comprehensive plan with a housing element. Going forward, zoning codes must defer and substantially reflect this plan.[67] By adopting a “consistency requirement,” such local plans act as a constitution to zoning’s statutes.[68] But this constitution should not be permanent: local plans should be updated at least every 10 years, in order to reflect a community’s development, while disallowing non-upzoning amendments in the meantime. The plan should be the single, real representation of allowable size and density that specific zoning reflects.[69] Any project that a reasonable person would deem consistent with the community’s comprehensive plan should be approved unless it violates health or safety standards.

Many states, such as Florida, already clarify that they have oversight of local plans based on established state goals and policies. The intent is to help localities figure out how to reconcile their current and future housing needs with local priorities; funding can be allocated to localities to ensure that they have the resources to properly plan.

These local plans can be strengthened by requiring that meaningful public engagement occur before the comprehensive plan is adopted instead of for individual zoning amendments or applications. Plans must also be consistent with local housing needs.[70] How states define their interests in local housing needs can vary, but they may include satisfying projected household growth in the plan’s housing element.[71]

In short, local comprehensive plans should have the force of local law. Jurisdictions should have a comprehensive plan as part of the enforceable rights granted to localities under the state zoning enabling act, ensure that zoning reflects that plan or keep the plan up-to-date, and demonstrate how their plan is consistent with local housing needs.[72] Guaranteeing that local plans are local law will: (1) ensure that local land use is still administered locally; (2) allow for predictability and transparency in planning; (3) productively channel local engagement in a regular process; (4) allow neighbors to prioritize their goals and conduct placemaking unique to their community; and (5) allow citywide bargains with a wider array of stakeholders rather than site-by-site battles.

Models

- Florida’s 1985 Local Government Comprehensive Planning and Land Development Regulation Act gave the state substantial oversight of local plans, based on established state goals and policies.[73] The state required and approved local plans as well as limited their amendment to twice yearly. Failure to have an approved local plan resulted in the loss of state revenue-sharing and grant dollars to local governments. Courts subsequently upheld the primacy of plans vis-à-vis zoning. The act was amended in 2011 to become the Community Planning Act, which restricted state and regional review authority and substantially diminished the state’s review process for local plans.[74] Yet it still required that the state and its local governments prepare and adopt comprehensive plans and had a limited “concurrency requirement” ensuring that sewer, solid waste, drainage, and potable water would be available to service new developments. Once adopted, the plan became a legal document, and all developments and actions of the local government were to be consistent with the plan. The plans are required to contain future land-use and housing elements that address zoning, the maintenance of the housing stock, and potential sites for additional housing. Florida’s local communities are still largely free to control land use as they see fit.[75]

- Minnesota statute 473.858 requires that zoning actions in the state must be consistent with the relevant jurisdiction’s comprehensive plan and not conflict with it in any way.[76] The comprehensive plan must also offer guidelines for easily translating its language into zoning.

Menu #2: Making Housing Pay Off

POLICY: Outcome-Based Housing Awards

State lawmakers should set clear goals for housing-market outcomes and tie these figures to carrots and sticks in funding. Those can be satisfied in two ways: (1) maintaining a price-to-income ratio that is equivalent to, at most, four years of statewide median household income to purchase the median home within the relevant city; or (2) including in its comprehensive plan or zoning ordinance at least three of the following recommended housing strategies, which largely reflect those in place in Utah to encourage the development of moderately priced homes.

Recommended Housing Strategies

- Zoning necessary to ensure the production of entry-level or moderate-income homes

- Facilitating infrastructure necessary to encourage the construction of entry-level or moderate-income homes

- Facilitating the rehabilitation of existing uninhabitable housing stock into entry-level or moderate-income homes

- Waiving construction-related fees that are otherwise generally imposed by the city

- Creating or allowing for, and reducing regulations related to, accessory dwelling units in residential zones

- Allowing for residential development in commercial and mixed-use zones or near major transit corridors

- Eliminating or reducing parking requirements for residential development

- Allowing for single-room occupancy developments

- Reducing impact fees

The state can financially reward localities that achieve meaningful affordability for working families—or penalize those that do not—by creating a grant program that directs additional funds to successful jurisdictions or including performance in any formula for the distribution of transportation funds or other intergovernmental dollars.

The state should direct larger local governments, in places with more than 100,000 in population, to annually report to the public housing-market outcomes, along with additional information on how many new housing permits are approved or denied every year and how long it took to come to either decision. Any jurisdictions that zone without a comprehensive plan should be ineligible for outcome-based housing awards and subject to inclusion of this status in the review of their eligibility for other state dollars, particularly for transportation.

With such measures, zoning and comprehensive plans can work together to result in meaningful improvements in the housing market—and the typical family might stand a chance of reasonably affording a home in areas of greater opportunity.

Models

- Utah’s Affordable Housing Modifications law, passed in 2019, required communities to develop a moderate-income housing (MIH) plan as part of their general plan.[77] The legislation provided a list of 23 strategies to encourage housing affordability, and it required cities to select at least three strategies (now increased to five) in order to be eligible to apply for $700 million in state transportation funds.[78] In the policy’s first year, three of the four most frequently selected strategies related to zoning reform.[79]

- Colorado’s HB22-1304, which was passed into law in June 2022, created two grant programs for communities to support affordable housing ($168 million) and invest in infill infrastructure ($40 million), respectively.[80] It tasked a multiagency group with developing a list of land-use best practices that, if adopted by an applicant community, would make it highly eligible for these dollars.

- Massachusetts’s Housing Choice Initiative rewards communities that are “producing new housing and have adopted best practices to promote sustainable housing development.”[81] Recipients are eligible for funds by either producing: (1) greater than 5% housing growth or 500 housing units over the last five years; or (2) greater than 3% housing growth or 300 units over the last five years and passing four of nine housing best practices. (Later, Chapter 358 of the acts of 2020 built on this initiative by amending the state’s Zoning Act to lower the threshold for local changes to zoning laws to a simple majority.)[82]

POLICY: Allow Housing to Pay Dividends

When municipalities allow new residential construction, they increase their property-tax base by a set amount, a portion of which can be shared with neighbors to lower their tax bills or fund improvements in their neighborhood. This is why states should allow and assist localities in instituting a tax increment financing (TIF) scheme—a “housing dividend”—that either: (a) rebates and reduces the property taxes of nearby owners for a period of time: or (b) funds road improvements, sidewalks, greenspace, and other public enhancements for a similar period. The idea of a housing dividend is based on the commonly used TIF tool that diverts future property-tax revenue increases from a defined area for a certain period of time toward public improvements, economic development projects, or affordable housing in the community.[83]

One approach—based on the tax increment local transfer (TILT) model proposed by Yale Law School’s David Schleicher—would be to transfer a quarter of the tax increment of new development with a residential component to owners in the relevant council member’s district for 10 years.[84] The amount of a tax rebate that the housing dividend would provide increases with the value that a new development offers. Given the recent nationwide run-up in home prices, a housing dividend could generate substantial tax cuts to neighbors.

Another approach would be to implement a TIF program to fund public improvements in fast-growing, in-demand neighborhoods in order to allay local fears that the infrastructure cost of new housing will outweigh its gains.[85] Cities can also designate that the incremental tax revenue come from specific revenue sources (e.g., multifamily housing, mixed-use projects) and have the freedom to adjust the benefits as local needs change (perhaps to help fund new schools for more children living in a neighborhood).

Since the funding arises only if revenue increases are realized, the availability of TIFs in a given area may incentivize both more development activity and government approval of that activity in order to realize future revenue for TIF-related investments or transfer payments. The more housing that is allowed, the more neighbors and the neighborhood benefit. The TILT version of a housing dividend offers an improvement on Community Benefit Agreements—which tax local developments to pay off interest groups for questionable outcomes—while the traditional TIF version of a housing dividend would be an improvement over impact fees, which are one-time user fees on new development that directly raise the cost of new housing. The benefit of a housing dividend approach is the flexibility that it gives to cities to target local needs.[86]

Models

- Texas’s more than 180 Tax Increment Reinvestment Zones (TIRZs) are TIFs that can flexibly be applied to a range of communities (they can be applied to underdeveloped or unproductive land, as well as in wealthy areas).[87] Taxing bodies within a TIRZ are allowed to set the portion of the tax increment they will use for a wide range of public enhancements within the zone, including affordable housing. Unique to this Texas TIF, private property owners can petition to create a TIRZ. Texas has not set a maximum time in which a TIRZ can operate, but they generally are on a 20–25-year term.

- Texas’s Homestead Preservation District (HPD) program, created in 2005, is a TIF zone that reinvests property-tax dollars into the development and preservation of affordable housing in that area.[88] With an HPD, a city can “offer tax-exempt bond financing, offer density bonuses, or provide other incentives” for housing affordable to “households earning 70 percent or less of the area median family income.” HPDs are limited to areas with a poverty rate at least twice that of the municipality, which includes many rapidly gentrifying areas; through an HPD, they can receive more affordable housing the more property values are maximized with development.

POLICY: Down-Payment Savings Program

States can help households struggling to save enough money for a down payment on a home purchase by allowing them access to a special savings vehicle and providing matching funds—from state, federal, and nonprofit sources—to help them save. Matching may be provided at a 2:1 ratio—two dollars matched for every one dollar saved—or preferably higher[89] for households that are below 200% of the federal poverty level and that either have a net worth below $15,000 or are receiving TANF or SNAP support. Such an account’s impact can be increased by covering tax liability on interest income incurred at the federal level, allowing for tax-free savings toward a down payment.

The goal for this “match to own” savings program—similar to what are known as individual development accounts (IDAs)—is to directly invest in households that are investing in themselves, rather than increasing household debt, as often happens with current state downpayment assistance loans.[90] States can partner with financial institutions to establish simple savings programs or pair them with more comprehensive financial education efforts provided through private-sector and nonprofit groups. (Studies suggest that simpler is better with downpayment savings programs like this.)[91] Additionally, states can ensure that households on Section 8 housing vouchers or residing in public housing are not penalized for increased income when used to save in a match to own savings program; similarly, saving for a home purchase would not be considered when computing asset limits for eligibility in TANF or food stamps. (A downpayment savings program must be accompanied by one or more of the other pro-home policies listed here, to ensure that this assistance to the demand side for housing does not worsen the housing shortage and affordability problem.)

Model

- Individual development accounts (IDAs) were first proposed by Brown University professor Michael Sherraden in his book Assets and the Poor: A New American Welfare Policy (1991).[92] He called for the government and the private sector to work together to create a system that incentivizes saving for homeownership, college education, self-employment, and retirement. IDAs were proposed as a matched savings program for low-income individuals paired with financial education and programmatic support. The idea quickly took off, and IDAs were included in the federal government’s 1996 welfare reform package as an option for states to pursue. By 1998, states were being offered federal financial support with Assets for Independence Act funds. By 2002, more than 500 IDA programs were operating across the country, mostly spearheaded through nonprofit groups. State-supported IDA programs remain less widespread, operating in at least 11 states as of 2021.[93] State-supported IDA programs generally involved a partnership between a state agency, a nonprofit service provider, and a financial institution.[94] Studies of IDA programs suggest that low-income participants of all racial and ethnic backgrounds were willing to make sacrifices to save, and successfully so.[95]

Menu #3: Streamlining Local Government

POLICY: Legalize Starter Homes

States should legalize starter homes. These are typically smaller homes that households and families can afford as their first property, helping them build equity for the long term. Unfortunately, many communities essentially ban starter homes by mandating larger, solitary homes on bigger lots that many young people and families cannot afford. They also often layer on additional requirements for parking and style that increase cost and may not be a fit for everyone.

States should explicitly legalize homes of 1,400 square feet or less, which is Freddie Mac’s definition of a starter home, and not mandate lot sizes larger than the maximum size of such a starter home.[96] Additionally:

- No discretionary review should be applied to the permitting of these housing types.

- No other regulations or fees should otherwise hinder the construction of these homes (such as through special setbacks, massing limits, excessive parking mandates, owner-occupancy rules, or conditional use zoning).

- Additional rules on the height and size of residential dwellings, as well as lot sizes, should not be allowed unless they are necessary to achieve a vital and pressing interest in allowing modest-size, entry-level homes and unless they otherwise do not exceed similar rules applying to other single-family homes in the relevant jurisdiction.

These measures can be gradually introduced by authorizing them when communities trip an automatic trigger, such as a certain price-to-income ratio. These rules can also be strengthened by allowing more than one home per parcel of land.

By legalizing starter homes, homeowners would enjoy a wider range of choice at a potentially lower price point and through a built form once common in American communities. Smaller homes on smaller lots can help young adults hoping to start a career or a family—particularly in places where they grew up that are now out of reach financially—as well as the teachers, police, and firefighters priced out of the communities they serve. Ultimately, homeowners, not governments, should choose home sizes.

Models

- New Hampshire’s HB 1807 prohibited lot-size requirements of more than 10,000 square feet for a single-family house, provided that water and sewer service were available, and clarified that state law does not limit the ability of communities to set smaller lot-size requirements.[97]

- Minnesota’s HF 3256 legalized starter homes by preventing cities from mandating minimum home sizes or specific building materials as well as by allowing up to two housing units on any lot.[98] In the Twin Cities metro area, the bill caps minimum lot sizes at the size of a typical lot in the area, roughly an eighth of an acre. The bill gave local governments more fiscal tools, particularly through impact fees, to pay for infrastructure. HF 3256 ended “zoning by loophole” by aligning local controls to comprehensive plans.

- California Assembly Bill 803 (Starter Home Revitalization Act) allows for single-family homes of 1,750 square feet or smaller to be built on multifamily lots without any special minimum lot-size or setback requirements.[99]

- In 2016, Massachusetts launched the Starter Home Zoning District to allow communities to welcome single-family homes no larger than 1,850 square feet on reasonably sized lots (depending on the underlying zone).[100] Since the program was originally limited to a few “smart growth locations” in the state and came with more stringent affordability mandates, Massachusetts is now considering adding an entirely new statute to allow starter home districts to be added wherever communities see fit and with much looser restrictions on price point.[101] Communities that adopt these Starter Home Zoning Districts will be eligible for additional state funding and bonus payments for each starter home built under the program.

- In 1998, Houston policymakers reduced the city’s minimum lot-size requirement from 5,000 square feet to effectively 1,400 square feet within the city’s I-610 Loop, before later expanding this deregulation to the entire city.[102] Tens of thousands of new, modest-size homes were subsequently built across the region, thus expanding homeownership opportunities for young families, funding improvements in old neighborhoods, and helping slow home price inflation across the region.

POLICY: Simplify Building and Design Rules

Rather than navigating widely varying building standards across different communities, states should set a statewide building and fire code that applies to all communities, which must, in turn: (a) reflect one of the nationally or internationally accepted codes already established;[103] and (b) be in a software-interpretable form (with software output indicative of code compliance).[104] While most states adopt minimum standards, these codes should instead be interpreted as maximum codes that localities may not exceed. Localities would still oversee compliance with building standards within their jurisdiction, but they should also be allowed to certify third-party inspectors who can, in turn, certify compliance with building rules.

States should also make clear that rules on compatibility or design are the exclusive province of community deeds—i.e., agreements between neighbors—and that construction that complies with such deeds will enjoy automatic local permit approvals. In this way, homeowners with very particular design preferences can opt in to them.

Models

- Kentucky’s “mini/maxi” building code is statewide, uniform, and mandatory.[105]

- Utah’s HB 98 allows builders to hire a state-licensed inspector if the city cannot complete an inspection within three business days.[106]

- Texas’s HB 2439, which went into effect in 2019, prohibits local restrictions on building materials.[107] The law also sets nationally accepted codes as the standards for cities to regulate construction within their boundaries.

- North Carolina’s SB 25 prohibits aesthetic requirements on one- and two-family dwellings statewide, except for safety or historic reasons.[108]

POLICY: Ban Housing Bans

States should ensure that all housing types are allowed—at least, in theory—and that a mix of land uses is possible but not mandated, without fear of future shadow bans. That is, local governments shall not establish outright bans on residential or mixed land uses or caps on residential building permits, and shall not otherwise establish a building moratorium except where there is a clear and serious threat to public health, safety, or welfare. (States may also disallow localities from downzoning properties that are already zoned with access to municipal water and sewer service.) Residential uses should no longer be banned from commercial office and retail spaces, and existing lots in these commercial zones should be allowed to be subdivided. These measures can be introduced slowly, in at least two ways: first, by limiting the openness to all housing types in theory to annexed or unincorporated land; and second, by limiting new residential housing in commercial areas to currently vacant commercial sites or sites with connections to side streets.

Examples of such bans, caps, and moratoria are easy to find. Roswell, Georgia, a suburb of Atlanta, banned new standalone apartments in May 2022.[109] Lakewood, Colorado, a fast-growing community between Boulder and Denver, approved a 1% annual cap on housing construction permits in 2019,[110] and a statewide ballot measure soon followed (yet failed, for now), in order to enact a similar limit in cities and towns along what is known as the Front Range, such as in Denver.[111] Dripping Springs, one of Texas’s fastest-growing cities, enacted a citywide building moratorium in 2021 that was meant to last just nine days and has instead stretched into 2022.[112] Many American locales already ban all housing in commercially zoned areas, even though the Covid-19 pandemic has boosted office vacancies, redevelopment would require little in the way of new infrastructure, and these areas often do not closely neighbor preexisting residential communities.

Models

- North Carolina’s Increase Housing Opportunities Act stated that a “local government shall not adopt or enforce an ordinance that establishes a ban or has the effect of establishing a ban on a use of land that is not an industrial use, a nuisance per se, or that does not otherwise pose a serious threat to the public health, safety, or welfare.”[113] This vision would help shift zoning back to its original vision as a form of “good housekeeping” and to push back against excessive regulation.[114]

- Arizona’s bipartisan bill HB 2674, among other measures, expressly allowed for the by-right construction of “single-family, two-family, and multifamily units” in commercial or mixed-use districts throughout the state.[115] For these mutifamily developments, the bill provided clarity on maximum height limits (which increased to 75 feet within a half-mile of transit stops or major freeways and arterial roads).

POLICY: Sandbox for Housing Innovation

Construction innovation often faces enormous regulatory and permitting hurdles, not to mention lengthy timelines even when approved, particularly when reviewers and codes tend to be risk-averse and highly discretionary. Most municipalities do not have codes related to, say, 3-D-printing a home. Moreover, new construction methods and materials are evolving faster than regulations can keep up. Rather than implicitly or explicitly disallowing all construction styles not explicitly allowed—or mandating that new building technologies and materials follow old regulations—a regulatory sandbox for housing allows for sensible regulations that encourage building innovations that ultimately improve housing and may lower costs.[116]

A regulatory sandbox for housing would allow for new housing construction technologies to be tested in the market for a short period—say, two to three years—without being subject to ill-fitting regulations at the state or local level. Applicants would be able to seek statewide preapproval for innovative housing and building techniques and components, such as for factory-built or modular housing, 3-D-printed construction, cross-laminated timber use, single-stairwell construction, and more. These plans can be tested and installed in controlled conditions in order to receive preapproval and with an understanding that real-life use cases will be used to evaluate which, if any, new or current regulations and oversight should apply throughout the state and to preempt relevant local rules. A statewide housing agency would act as liaison within state government and to local lawmakers.

Applicants would have to show how their offering was still subject to regulations or permitting outside the sandbox, demonstrate which laws or regulations the applicant seeks to be waived or suspended during their time in the program, how their offering benefits consumers as well as what risks they may face, why participating in the sandbox would be beneficial to the applicant, and how their offering is unique and will be demonstrated in the current marketplace.

Models

- Arizona’s HB 2673, known as the “Property Technology Sandbox,” offers emerging products and services in the real-estate industry a two-year trial period, overseen by the Arizona Commerce Authority, in which to test out technologically innovative products and services before applying for formal licenses and authorizations.[117] Proptech companies file an application with the Arizona Commerce Authority to participate in the sandbox. The state does not currently allow “products or services related to the physical new construction of improvements to real property” to participate in the sandbox program.

- Utah’s HB 217, signed into law in 2021, created a first-in-the-nation all-inclusive regulatory sandbox program.[118] The program broadly applies to the “use or incorporation of a new idea, a new or emerging technology, or a new use of existing technology … to address a problem, provide a benefit, or otherwise offer a product, service, business model, or delivery mechanism.” The bill created the Utah Office of Regulatory Relief within the Governor’s Office of Economic Development to oversee the program.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).