De-Municipalization: How Counties and States Can Administer Public Services in Distressed Cities

In June 2019, America marked 10 years since the end of the Great Recession. For many state and local governments, the recovery has been slow and remains incomplete. Cities face the most serious challenges of all.

The legacy of deindustrialization still weighs heavily on dozens of municipalities across the nation, creating tax bases far weaker than is the case with any state. Several indicators, such as trends in local aid, state and local government employment, and spending on Medicaid and retirement benefits, suggest that this is a new era for state and local finance. New administrative or institutional adjustments will therefore be necessary.

Many such adjustments have already been made by states and cities. Municipal bankruptcy prior to 2008 was a subject of mostly academic interest, but it now stands at the center of policy discussions about how to assist distressed cities. Short of bankruptcy—or in addition to it—states have experimented with a variety of oversight and intervention tactics. Municipal fiscal strain has also given new urgency to old ideas, such as regionalization.

More needs to be done, and this report proposes the broader use of “de-municipalization.” Instead of taking over entire city governments on an emergency basis, governments at the state or county level should take over large city agencies, such as a police department, on a presumptively permanent basis. In some cases, the city could still be expected to fund all or part of the service; in others, financial responsibility could be assumed by the county or state. Even when continuing to be responsible for funding a service, a distressed city could still realize financial benefits from de-municipalization, such as through restructuring union contracts.

Compared with other responses to municipal bankruptcy, de-municipalization has the following advantages:

- Municipal bankruptcy is difficult for cities to enter. It cannot be used on a preventive basis but only—indeed, this is a requirement of federal law—after all other efforts to reinstitute fiscal stability have failed.

- Though state takeovers are more common than bankruptcies, state officials often lack the capacity to understand every operational detail before they assume full control. State takeovers are often made politically palatable when they are executed on an emergency basis, even though a city that has been in decline for decades may need more than a few years to be restored to stability.

- Regionalization is not sufficiently targeted to the problem of fiscal strain; and economic strategies, such as Opportunity Zones, hold out unrealistic hopes that cities can grow their way out of their struggles. De-municipalization offers place-based policy support to distressed urban areas but of a fiscal and administrative, not an economic, character.

The following analysis explores the main features of de-municipalization. It will explain how this strategy benefited the city of Camden, New Jersey, and how it should fit in the context of a broader response to municipal fiscal distress, one that still includes the use of traditional takeovers and bankruptcy.

Camden: How De-Municipalization Helped1

Camden, New Jersey, is located in the southern part of the Garden State, across the Delaware River from Philadelphia.[1] At 37.4%, its poverty rate is the fourth-highest in the nation, among the roughly 630 census-designated places with a population of at least 60,000. The city’s population has declined 40% since its peak during the post–World War II era. The local tax base is extraordinarily weak and funds only a small fraction of the cost of municipal government (Figure 1). In 2017, property taxes accounted for $26.5 million of the city of Camden’s $192.2 million “current fund,” or nonschool, budget.[2]

Camden has repeatedly struggled to pay for public services throughout its decades of decline. In a 2013 report, the Pew Charitable Trusts suggested that Camden “may never be self-sufficient,” noting that “New Jersey has tried just about everything to help Camden,” including an array of loans, grants, and economic development assistance, even offering funding for local colleges and health-care centers.[3] The city was under the control of state government from 2002 to 2010.[4]

A new approach was taken in the wake of the 2008–09 recession. The Camden Police Department was dissolved and replaced by the Camden County Metro Police. Formally launched in 2011, the Metro force now provides policing services in the city of Camden, while operating under the governance of the county board of freeholders. This restructuring was prompted by a combination of recession-era fiscal weakness, a rise in crime, and a restrictive union contract that prevented municipal authorities from deploying resources as efficiently as possible. A broad array of supporters included state legislative representatives from Camden, then-mayor Dana Redd, county officials, and the administration of then-governor Chris Christie. The overall structure of the new policing strategy was laid out in a 2011 report commissioned by Camden County officials and authored by John Timoney, who had served in high-ranking positions in the police departments of New York City, Miami, and Philadelphia.[5]

Under the new police department, crime has dropped significantly (Figure 2 and Figure 3):

Strictly speaking, county government formed a new countywide department that was available to all cities and towns in Camden County, but only the city of Camden has taken advantage of this option.[6] (While counties in New Jersey do perform some public safety functions, such as operating jails, only Camden County has a municipal police force.) Neither the state nor the county took fiscal responsibility for policing in Camden. And, according to decisionmakers involved in the process, that was never under consideration. The city of Camden still pays for its policing services, at an annual cost of $3.1 million in FY17.[7]

The Timoney report called for taking “the current model of reactive policing in Camden City to a new dimension by incorporating proactive policing” while maintaining “the necessary emergency services.” This proactive dynamic included a community policing division dedicated to “engag[ing] with the neighborhood and community in order to address quality of life issues.” Only a few years into its existence, the U.S. Department of Justice recognized the Camden County Police Department for its work on reducing gun-related homicides, and President Obama recognized its work in community policing.[8] The leadership of the new police force was able to fully execute its community policing strategy because of an entirely new police contract. Though most of the current county force were members of the former city police department (including the current chief), the old contract between the city of Camden and the Fraternal Order of Police, Lodge No. 1 was dissolved. Police in Camden are unionized, but they had to negotiate an entirely new contract with a new local, Fraternal Order of Police, Lodge No. 218. Past practices, such as heavy reliance on highly paid uniformed staff to perform administrative duties, were phased out. Following the recommendations of the Timoney report, and owing to the flexibility afforded by the new contract, the number of cops on the streets has doubled.[9]

De-Municipalization: The Proposal

The experience of Camden suggests the advantages of de-municipalizing a core service, such as policing. New leadership, at another level of government, may assume control when city leadership has been found unable to perform a basic service function. Essential to the restructuring of policing services in Camden is that the new arrangement is permanent. This important fact reflects a belief that in guaranteeing a stable level of public safety in Camden, it should be assumed that county authorities will be in charge indefinitely. It also reflects a belief that Camden will not be able to grow its way out of fiscal and economic troubles anytime soon. While economic development efforts by former governor Chris Christie’s administration gave a degree of urgency to the restructuring of policing in the city, the results remain modest.

Camden is not the only poor city in the nation that has experienced inadequate municipal services owing at least in part to a chronically weak tax base. Public safety is a core function of government. In contrast to, for example, single-payer health care or paid leave, there is no serious dispute that public safety is the responsibility of government. In addition, there has long been an expectation that public safety should be provided by municipal authorities. That second expectation needs to be reassessed.

More officials, facing situations similar to Camden’s during the last recession, should explore a similar takeover approach that is targeted, but permanent, with the goal of stabilizing municipal services. Instead of intervening on an emergency basis and asserting control of an entire governmental entity, de-municipal interventions take over only a certain municipal agency but on a permanent basis. The state or county government could assume responsibility for one service, leaving the rest under the control of city officials. The goal should be fiscal and administrative reform of cities that are both very poor and are operating with inadequate service levels.

The question of whether the county or the state is best positioned to execute a de-municipalization plan will depend on the jurisdiction. The role of county government differs across American states. In some New England states, counties are not much more than a geographic designation. The decision as to whether state or county government is the more logical entity to take the lead in a de-municipalization effort bears on the question of how to devise participation by local stakeholders. In the Camden case, the city has representation on the Camden County board of freeholders. One of the seven at-large members is from the city, which is roughly proportionate to the city of Camden’s share of the county’s population as a whole. The offices of Camden County government are in downtown Camden, a five-minute walk from Camden City Hall. In other jurisdictions, where it is more logical for state government to assume control of a municipal department, some form of advisory board will have to be created. Though some have proposed creating new authorities to address the new or newly urgent threat of distressed governments,[10] the multiplication of government forms should be avoided as much as possible.

Moral hazard is a serious concern in any discussion of how to respond to municipal distress. All cities are interested in maximizing their access to funds that they did not have to raise themselves, just as they are interested in minimizing the restrictions on the use of those funds and the conditions attached to receiving them. A bailout can lead to the weakening of fiscal discipline in a poor city that’s operating with a slim margin of error. In 2018, city officials in Hartford, Connecticut, abandoned a proposal to transition nonunion city workers to a defined contribution retirement benefit plan. This proposal was developed the previous year, when Hartford faced an insolvency crisis that was resolved with a $500 million financial assistance package from state government. The state fiscal rescue thus plainly led to a slackening of fiscal discipline in Hartford, as well as calls for financial assistance from officials in other poor Connecticut cities.[11] In a de-municipalization effort, moral hazard can be neutralized by making clear that city officials must relinquish control and accept an indirect or advisory role. The threat of a loss of power will deter opportunistic requests for no-strings-attached support.

Even when de-municipalization brings no direct fiscal benefit to the distressed city, the creation of an entirely new agency could very well provide fiscal benefits, such as through a “reset” effect on union contracts. But states should consider assuming fiscal, as well as administrative and political, responsibility. Among other reasons, this would make de-municipalization more palatable to local officials who stand to lose power. Of course, some sort of local contribution could still be required.

States and counties are not in a position to assume responsibility for all services in cities with below-average income levels. They are, however, in a position to assume responsibility for certain services in a select number of poor cities. States’ tax bases are generally much stronger than those in such cities. Only two states have a poverty rate of more than 20%: Mississippi and New Mexico. Of census-designated places with a population of more than 60,000, about 180 have a poverty rate of more than 20%, and 26 have a poverty rate of more than 30%. The breadth and relative resiliency of states’ tax bases means that they will be able to assume responsibility of municipal functions, as long as the cases are considered exceptional.

The boundary between state and city affairs differs between jurisdictions. It has also been in dispute throughout American history. On the one hand, the U.S. Constitution views city powers not as inherent but as granted by state government. On the other hand, so-called Home Rule legal regimes enacted by state legislatures have created protected spheres of authority in which city governments may act freely.[12] The passage of Home Rule–style laws in almost every state reflects a political or cultural reality that Americans, stretching back to the colonial era, have always expected at least a degree of deference toward local government. States have, at certain times and places, acted aggressively to assert control over municipal operations, including police departments.[13] But that has not been the general tendency among state governments in recent years. Among the reasons that state officials tend to be reluctant to intervene include the risk that they would be held responsible for a crisis that might develop over decades of local control—as well as the simple fact that local government is popular. According to polls, the public has a more “favorable”[14] opinion of local over state government and tends to trust it more.[15] Governor Chris Christie’s takeover of Atlantic City, which many now view as having contributed to the stabilization of that city’s finances, was originally denounced as a “fascist dictatorship” by the mayor of Atlantic City.[16]

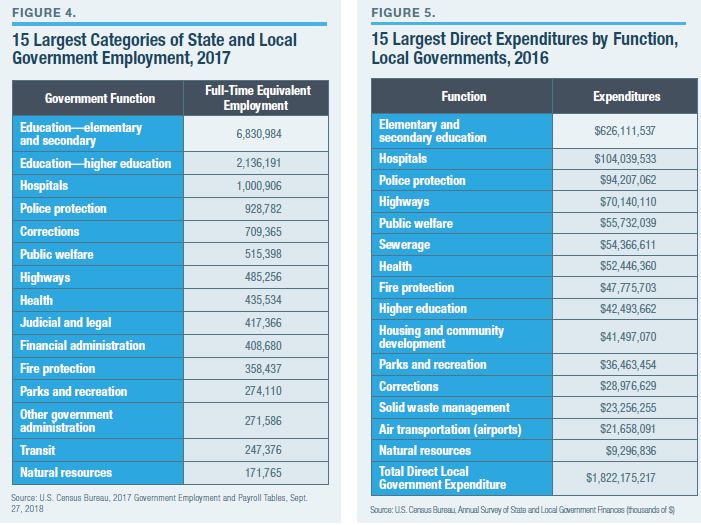

Public safety services are the most natural candidates for de-municipalization because of their outsize fiscal burden (Figure 4 and Figure 5) and their indisputable status as core services. K–12 public education already functions under a well-developed regime of state oversight and funding. De-municipalization efforts that target K–12 would be best advised to work within those existing regulations and governance structures. However, in some jurisdictions, other services, such as parks, libraries, or infrastructure maintenance, may also be a more logical candidate for state or county control.

The Case for Urgency

In recent years, the fiscal condition of states and cities has gradually improved. No major city has declared bankruptcy since Detroit in July 2013. Borrowing costs for states and cities remain near their lowest levels since the 1960s, attesting to sustained investor confidence.[17]

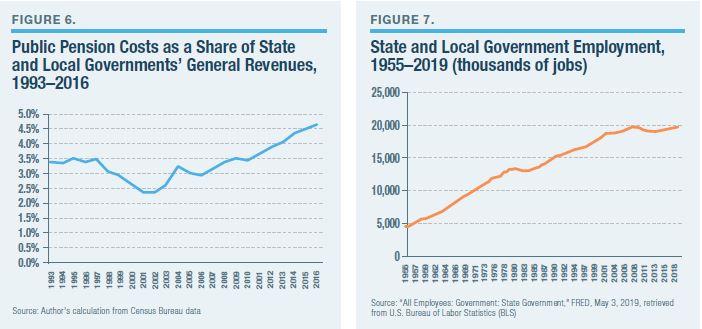

Nevertheless, many signs of structural weakness remain. The National League of Cities’ most recent survey of city financial officers found that revenue growth slowed for the second consecutive year and failed to keep pace with the increase in general fund expenditures (as has been the case in three of the last five years).[18] Measured as a share of revenues, state and local pension obligations stand near a historical peak,[19] despite a nearly 300% increase in the Dow Jones Industrial Average since March 2009. The pressures in servicing public retirement systems’ debt-like obligations place direct stress on cities, due to costs relating to their own systems,[20] and indirectly, by reducing states’ available resources to fund local aid programs. Since the early 2000s, pension costs have been growing more rapidly than revenues (Figure 6).

Pensions may still represent only 5% of total general revenues, but when they increase more rapidly than revenues, it is difficult for government services to improve in concert with improvements in economic conditions. A 2016 analysis by scholars affiliated with the Rockefeller Institute found that, between 2007 and 2015, pension expenses consumed 59 cents for every $1 increase in state and local tax revenue.[21] Pension costs will have to continue to rise since, among other reasons, many state and local governments still do not contribute adequately to their systems. The amounts represented in Figure 6 reflect only what states have been paying, not what actuaries recommend that they pay. Of the 166 systems for which 2017 data were available through the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College’s Public Plans Data website, 147 paid less than 100% of their actuarially recommended contribution that year.[22]Medicaid is another program whose associated costs have grown more rapidly than revenues, thus “crowding out” room in budgets for other priorities. The Pew Center on the States documented that, nationwide, Medicaid consumed 17% of states’ own source revenues in 2016, up about 5 percentage points since 2000.[23]

In other words, states have been dealing with a serious crowd-out problem for about two decades.[24] It is a given that states and cities must balance their budgets, and yet when certain expenditures consistently rise more rapidly than revenues, it follows that other services and programs will see their funding reduced.

Another indication that states and cities now face a uniquely challenging fiscal outlook is the fact that government jobs have not yet recovered since the Great Recession. Private-sector employment surpassed its prerecession peak in March 2014 and has continued to grow; state and local jobs are, as of April 2019, still about 60,000 below their August 2008 level of 19.8 million (Figure 7).

The recent plateau of state and local employment should be seen as evidence of structural weakness in government finances more than a broad embrace, among the public or politicians, of “right-sizing” workforces. The U.S. population is not expected to plateau,[25] and, generally speaking, the public favors small class sizes and rapid response times to calls for services, which require comfortably staffed municipal governments.

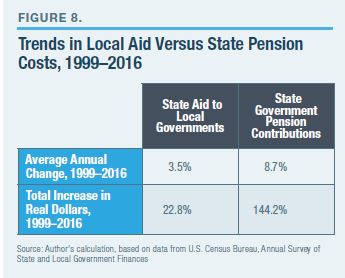

One casualty of crowd-out has been intergovernmental transfers or local aid (Figure 8). State pension costs have grown at six times the rate of local aid over the last two decades.[26]

One casualty of crowd-out has been intergovernmental transfers or local aid (Figure 8). State pension costs have grown at six times the rate of local aid over the last two decades.[26]

Aid reductions, though unpopular among local government officials and advocates, should be seen within the broader state fiscal context, which is defined not only by pressures relating to Medicaid and pensions but also obligations to support higher education, infrastructure, mental health, and various social-services programs. In an era of modest revenue growth such as the present, an increase in local aid would have to mean proportionate reductions in funding toward those priorities. In sum, states are more poorly positioned to fund unrestricted general aid to localities than they have been in the past.

Current Options for Fiscal Distress: A Critical Survey

Bankruptcy

Municipal bankruptcy is a process by which a debtor city can, with the approval of a federal judge, restructure and reduce financial commitments such as retirement benefits and bonded debt. Federal law makes municipal bankruptcy difficult. A city that wants to enter bankruptcy must demonstrate that it is insolvent on a cash-flow basis, must be authorized to file for bankruptcy by its state government, and must have made a good-faith effort to negotiate with its creditors prior to filing.[27] Bankruptcy can be an expensive process—and an uncertain one. In its 2013–15 bankruptcy, Detroit spent $100 million on fees for lawyers and consultants. The city took about one and a half years from the filing of its bankruptcy petition to its formal exit (July 2013–December 2014), whereas, in the case of San Bernardino, California, that process took almost five years (July 2012–June 2017).[28]

Bankruptcy will continue to be part of the discussion over solutions for municipal distress, if for no other reason than the experience of Detroit. Detroit has of late been the subject of several positive journalistic accounts of improvements in the local economy and quality of life. In February 2019, Moody’s commended Detroit for a “surge” in the city’s “employment base and tax revenue.”[29] Though it has yet to return to investment-grade status, late last year, Detroit did return to the municipal market with a $135 million offering of general obligation bonds.[30] Detroit exited state oversight—which it had been under since spring 2013, and throughout its bankruptcy[31]—in April 2018. Post-bankruptcy, many of Detroit’s fundamentals, such as the poverty rate (second-highest among the roughly 630 census-designated places with a population above 60,000), remain weak relative to other cities. But contributing to the positive view of bankruptcy’s impact on the city’s current recovery is the understanding that Detroit’s was not only the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history (measured in terms of the amount of debt); it was also likely the most complicated because of the many complex financial instruments or gimmicks that the city developed in hopes of staving off insolvency. Kevyn Orr, the emergency manager who directed the city’s bankruptcy, famously referred to his task as the “Olympics of restructuring.”[32] Detroit set a powerful precedent for other, smaller cities with less complex debt arrangements that stand on the verge of insolvency.

However, bankruptcy will still be rare, mostly because very few cities will be able to pass the entry requirements set by federal law. Bankruptcy remains only a viable option for a city past the point of insolvency. It cannot address distress until distress has transitioned into outright insolvency.

Takeover

Takeovers by state governments are much more common than bankruptcy. States take control of a city via a control board mechanism (New York City during its 1975 fiscal crisis; Springfield, Massachusetts, 2003–09), or by installing an emergency manager (used by Michigan in 13 localities—in some cases, more than once, over the past 30 years).[33] Takeovers are often justified as a way to avoid bankruptcy, although some states have combined the two processes.[34] The state assumes control of approving, or even crafting, budgets and financial decisions. The state may also direct restructuring municipal services. Takeovers are typically executed on a temporary basis.

The two highest-profile recent cases of a state takeover are Atlantic City, New Jersey; and Flint, Michigan. Their experiences were quite different.

Atlantic City’s economy went into sharp decline slightly before the 2008–09 recession due to a contraction in the local casino industry. From the 1970s to the early 2000s, the city had enjoyed an East Coast monopoly on gaming that was threatened by the opening of casinos in neighboring states. Since gross revenues peaked in 2006, Atlantic City casino revenues have fallen by over 50% in real terms.[35] After hovering in the 22%–25% range for the four prior decades, the city’s poverty rate recently spiked to more than 35%.[36] Five major casinos have closed, and the remaining casino owners have repeatedly appealed to the city to reassess their property valuations to reflect the decline in their businesses. These appeals have often been successful, forcing the city to issue hundreds of millions of dollars in bonds to refund the casinos for their artificially high property-tax bills. This surge in new debt, coming at a time of rapid decline in the local tax base, exacerbated the city’s distress. In January 2015, an emergency manager was appointed by Governor Chris Christie. State oversight was further formalized by the passage, in May 2016, of the state Municipal Stabilization and Recovery Act.[37] That legislation, which remains in place, gave New Jersey’s Department of Community Affairs broad authority over Atlantic City’s finances and operations. When Governor Phil Murphy came into office in 2017, he appointed a special counsel to continue to exercise oversight,[38] which is now expected to be phased out, in accord with state law and a strategy devised by the special counsel,[39] by 2021.

Credit rating agencies have viewed oversight of Atlantic City in a positive light. In upgrading the city’s bond rating to B2 last November, Moody’s specifically cited the “material budgetary improvements” and “the continued, strong oversight by the State of New Jersey” as a reason for that action.[40] Under state oversight, the city has negotiated critical agreements with the casinos over the property-tax valuation dispute and has reduced spending. The Murphy administration has been monitoring the progress of its own oversight and administrative efforts in Atlantic City through quarterly progress reports.[41] In addition to the relative stability of the city’s finances, bipartisan support for state oversight in Atlantic City is another measure of its success. Governor Phil Murphy, a Democrat, criticized the emergency-manager approach taken by his Republican predecessor, Chris Christie, during Murphy’s 2017 gubernatorial campaign. But his actions since assuming office show that he has found state oversight to be a useful policy strategy.

Most observers view Michigan’s role in overseeing the Flint city government in a much more negative light than the case of New Jersey and Atlantic City. Though the proximate cause of Governor Rick Snyder’s placing Flint under an emergency manager in 2011[42] was underlying fiscal distress, the state involvement is now most strongly associated with the city’s water crisis.

For years prior to the installment of an emergency manager, local leaders in Flint had been in discussion with other communities in the region about switching its water source from the Detroit Water System to a local custom-built system. This strategy was premised on a belief in the benefit of local control and hopes that it could bring water bills down. The idea of participating in a new regional water system had broad support among city officials. But prior to the opening of the new system, Flint, under the control of an emergency manager, opted to use the Flint River as an interim supply, using a system of pipes that had not been in use for more than a half-century. Due to inadequate treatment controls, dangerous levels of lead and other contaminants began to appear in the city’s water, eventually leading to an international scandal. Michigan’s emergency management plan and two emergency managers were indicted on charges, along with several state officials.[43] When testifying before Congress about the Flint water crisis in March 2016, Governor Snyder was asked: “Did that emergency manager system fail under your leadership in this instance?” Governor Snyder conceded: “In this particular case, with respect to the water issue, that would be a fair conclusion.”[44] Snyder left office in 2016 and, at present, no Michigan locality is under a state-appointed emergency manager.[45]

Some fiscal experts have speculated that, in the wake of the Flint crisis, Michigan has laid to rest its program for emergency management.[46] In June 2018, the Michigan state treasurer announced that no locality was under the supervision of an emergency manager, for the first time in almost 20 years.[47] Flint highlighted the risk of assuming responsibility for an entire city government—all of its departments and operations. This risk accounts for why, even before Flint, state officials across the nation were often reluctant to intervene aggressively in cities with a long legacy of poverty and fiscal distress.

Two other recurring themes are the need for talent and the temporary character of most takeovers. Finding emergency managers who are both qualified and willing will no doubt be more difficult after Flint. The supply was already limited because of the high premium placed on appointing a member of a minority group to serve as emergency manager in a majority-minority city, especially if a nonminority gubernatorial administration is ultimately directing the effort. The politics of state takeovers are highly influenced by such racial considerations.[48]

The temporary character of interventions drives much of the emphasis on participation by local stakeholders. A temporary intervention is often said to need substantial local buy-in, to ensure that the reforms remain in effect when state officials leave the scene. The Pew Center on the States has argued that local participation is one of the most important features of effective state interventions.[49] At the same time, too much deference to local officials undermines the premise of state involvement. A state appointee is ideally positioned to play the “bad cop” and make decisions that local officials cannot make because of political pressure. Broad stakeholder buy-in is less of a concern in permanent interventions because the officials who execute the initial intervention will remain to implement their reform program over the coming years. The temporary character of interventions intersects with the talent question, since only an excellent state appointee, with a special set of political and managerial qualities, will be able to enact structural reforms within a compressed time frame. Excellence becomes less crucial when interventions are permanent.

Regionalization and Opportunity Zones

Proposals to merge or consolidate local government units—regionalization—have been discussed for generations. They are often put forth by state officials who believe that fewer municipalities will lead to more efficient municipal service delivery, or will fulfill a social aim.[50] However, regionalization is a questionable response to the specific challenge of municipal fiscal distress. Research by demographer Wendell Cox has identified a correlation between smaller local government units and lower taxes and spending.[51] To result in major savings, the merger or consolidation of local government units would have to result in cuts to personnel spending, lower compensation, or fewer workers, which is often an unpopular proposition among the public and government unions.

The Trump administration has promoted Opportunity Zones as a solution to economic distress.[52] Provisions in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act allow investors in census tracts designated as a Qualified Opportunity Zone to defer capital-gains taxes at least until 2026—and permanently, if they maintain their investment for 10 years.[53] About 8,800 communities across the nation have been designated as Qualified Opportunity Zones.[54]

Providing advantageous tax status to poor areas, in hopes of stimulating economic development, has also been under discussion for decades. Jack Kemp, a former New York congressman and secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, was a notable proponent who saw what he termed “Enterprise Zones” as an alternative to the centrally planned urban-renewal strategies of the 1950s and 1960s. Though initially premised, in part, on the idea that excessive levels of federal taxation weaken local bases, at least 40 states have attempted their own place-based tax-incentive programs.[55] Researchers generally view these programs’ results with ambivalence.[56] Place-based economic development programs run a great risk of redistributing economic activity within a region (as opposed to yielding net gains of investment, jobs, and tax revenues), providing a taxpayer subsidy for a venture that a business would have pursued without the subsidy, and forgoing hundreds of thousands of dollars in tax revenue for the creation of a modest number of jobs. The Trump administration has argued that its program is informed by past critical research about place-based incentives.[57]

But the deeper difficulty with Enterprise or Opportunity Zone–type approaches may be less that they are place-based than that they are an economic strategy. It is rare for a city, after having become poor, to restore the local economy and tax base to median measures of health. A 2017 analysis, written by this author about Rust Belt jurisdictions, found that of the 96 poorest cities above 60,000 population in midwestern and northeastern states, nearly all have seen their poverty rates increase faster than their state governments’ since 1970.[58] Place-based fiscal or administrative policies are easier to justify than economic variations because their purpose is simply to secure the conditions for growth in chronically poor communities.

Conclusion

In recent years, discussions of how governmental structures may need to change in order to respond to fiscal distress have been overshadowed by discussions about preemption.[59] Scholars who have been debating the boundary between state and local affairs have focused on tensions between conservative state legislatures and cities that have been taking the initiative over the minimum wage and other social and environmental issues of great concern to progressive city leaders. De-municipalization, however, involves cities where the structural weakness in their local economies and budgets renders them no longer capable of meeting residents’ basic expectations for core municipal services. Municipal autonomy is not the problem facing cities like Flint or Camden.

In many statehouses, particularly the 14 under complete control of the Democratic Party,[60] legislators and executives are implementing or considering a raft of new spending initiatives, such as single-payer health care, paid leave, and universal prekindergarten.[61] In light of states’ strained finances and existing ambitions, it may seem gratuitous to call for them to assert responsibility over traditionally municipal policy responsibilities. But from another perspective, de-municipalization could be seen as a fix-it-first approach to government services.

Unlike corporations, cities are never truly free to fail. Even after decades of depopulation, high crime, and economic decline, communities such as Camden have remained home to tens of thousands of residents with high service needs. Often, the quality of municipal services in poor cities is due to nonfinancial factors such as mismanagement and corruption. But inadequate resources are usually a factor as well and may even be a driving cause. When core municipal services are not being delivered in poor cities, states and counties have an obligation to intervene.

The least that can be said is that, before expanding government, states should take stock of their ability to meet their current obligations and prepare for the next recession. That should entail not only fiscal preparations but also administrative preparations, to ensure that they have the right institutional responses in place to meet challenges at the state and local levels.

Relative to bankruptcy, and traditional state takeovers, de-municipalization should be seen as a both/and position, not either/or. De-municipalization offers the chance to expand the number of options that a state has at its disposal. Its virtues are best seen in contrast to those approaches and in the context of a broad strategy to address municipal fiscal distress:

- Opportunity Zones and regionalization are poorly targeted toward the problem of fiscal distress. Other interlocal responses to fiscal distress include contracting services out to a nearby government,[62] entering into a shared-services agreement,[63] or merging with a more economically viable neighbor.[64] But mergers or quasi-mergers between two communities that differ dramatically in size and fiscal capacity are likely to occur only as a result of leadership by state government. Instead of trying to transfer responsibility of funding policing services in a distressed city to a neighboring suburb, or several nearby suburbs, states might find it more practical to assume that responsibility themselves.

- Unlike bankruptcy, de-municipalization can be used as a preventive approach to insolvency. And in contrast to takeovers, the permanent and more targeted character of intervention in one municipal service may appeal to state officials who want to avoid a Flint-like debacle. Permanency is crucial because it signals a recognition of a “new normal” in municipal finance. The permanence of the arrangement will also place less of a necessity on talent than a traditional takeover because it is easier to reform a municipal government when given an indefinite time horizon rather than one of less than five years.

- Due to concerns over race and localism, de-municipalization will always carry political risks, but so, too, do traditional takeovers and bankruptcies. In some ways, de-municipalization of one service might strengthen local self-government vis-à-vis other functions. The offer of assuming fiscal responsibility may help assuage political concerns.

State and county officials are not inherently wiser or more competent than city officials. Indeed, as their pension funding struggles attest, states and counties have a long record of fiscal and administrative mismanagement. When, during New York City’s 1975 fiscal crisis, the state of New York took over the City University of New York, it failed to arrest the ongoing decline of that formerly strong institution.[65] Nevertheless, states, as well as some counties, are usually the only entities in a position to move promptly to address fiscal distress. Residents of poor cities have more to fear from states and counties ignoring their responsibility than from an overly aggressive intervention agenda. In a well-designed system of responses to fiscal distress, all parties would view de-municipalization similarly to municipal bankruptcy: a rare occurrence but one that is more common than in the past.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).