Coronavirus Budget Projections Escalating Deficits and Debt

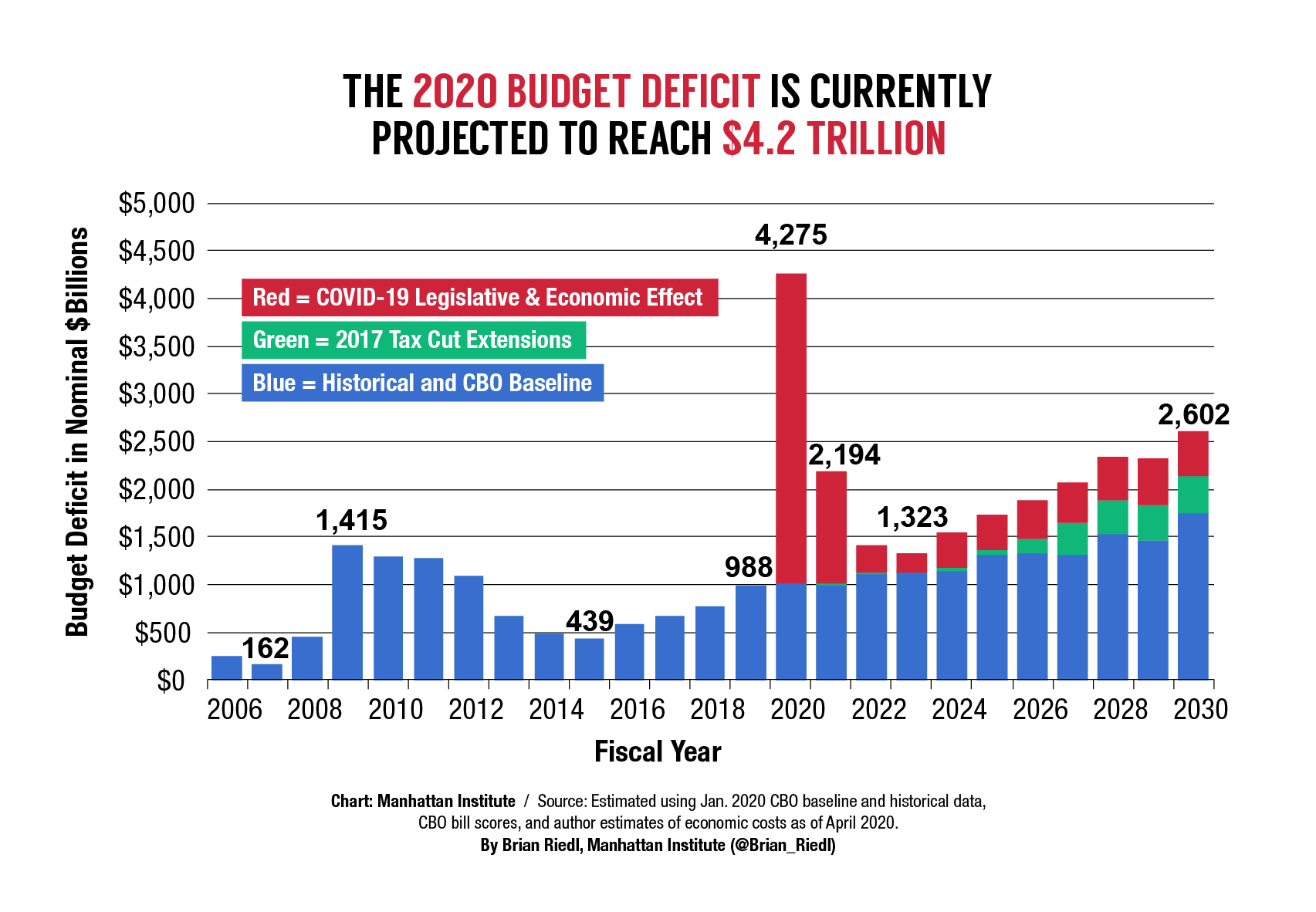

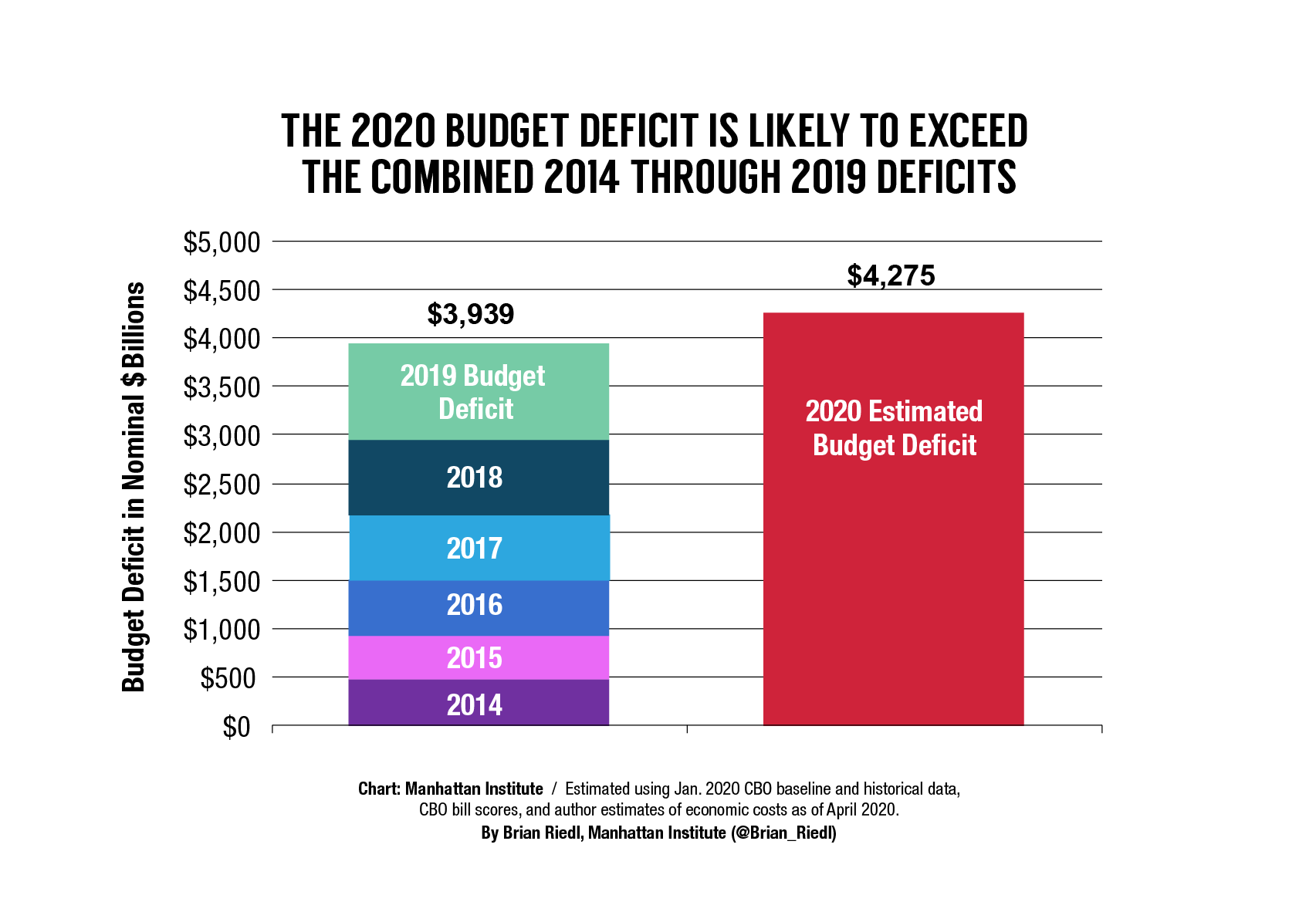

Added costs and declining revenues stemming from Covid-19 will produce a 2020 budget deficit in excess of $4.2 trillion. This is slightly above the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) April 24 estimate of $3.7 trillion for the year.

The baseline deficit entering 2020 was $1.0 trillion. CBO projects that the first four coronavirus response bills will add $2.2 trillion to this year’s deficit. The remaining portion of the deficit consists of the economic and technical effects of the economic shutdown—the non-legislative costs such as fewer workers paying taxes and more people signing up for unemployment and Medicaid benefits. This analysis assumes approximately $1 trillion in these costs (bringing the total deficit to approximately $4.2 trillion), while CBO presumably assumes a smaller economic and technical figure to reach its $3.7 trillion total.[1]

The $1 trillion non-legislative cost figure consists of automatic revenue declines equal to roughly 4% of GDP and higher automatic safety-net spending equal to 0.6% of GDP (again, this is separate from the cost of new legislation). These figures roughly match the economic and technical budgetary costs of the Great Recession at its peak levels. The coronavirus recession is expected to bring a larger drop in GDP but a smaller decline in stock values and investment taxes. Any additional legislation will further raise the deficit.

The $4.2 trillion budget deficit would represent 19% of the economy—the largest share in American history, outside the peak of World War II, and double the 2009 level during the Great Recession. In nominal dollars, the annual budget deficit had never before exceeded $1.4 trillion.

In 2020, the federal government is projected to spend $49,000 per household—by far, the largest total ever. Federal spending is projected to rise to nearly 29% of the economy, while revenues are projected to collapse to just 10% of the economy.

Even if the economy recovers quickly after reopening, the projected budget deficit will still approach $2.2 trillion next year and never again fall below $1.3 trillion. Combined with the mounting costs of Social Security and Medicare, the deficit will rise to $2.6 trillion by 2030 and continuing growing thereafter.

Over the full decade, the coronavirus recession is projected to add nearly $8 trillion to the national debt, pushing the debt held by the public to $41 trillion within a decade, or 128% of the economy. This would exceed the national debt at the height of World War II. Although that war ended before the debt could rise further, the expanding Social Security and Medicare shortfalls will keep the current debt increasing.

The $8 trillion coronavirus tab represents as much new borrowing as Washington had been projected to cover in the next six years. That essentially moves up the previous projections of the federal debt by six years and gives lawmakers six years less to avert a potential debt crisis in which rising debt and interest costs would overwhelm Washington’s ability to tax or borrow. As soon as the economy recovers, lawmakers will face pressure to get America’s fiscal house in order.

These figures assume that much of the economy reopens by early summer, and they do not account for future legislation to aid state and local governments and to provide additional broad economic assistance. As these unsustainable costs rise, it is vitally important for lawmakers and governors to find a safe way to reopen the economy, and—once the economy recovers—to begin to address the stratospheric rise in government debt.

Endnotes

- Differing interest-rate assumptions may also partially explain CBO’s lower projected deficit. However, CBO has not released its assumptions on that.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).