Classical Education: An Attractive School Choice for Parents

Introduction

Parents looking for an alternative to traditional public schools have an option that fell out of fashion in this country a long time ago. This option—called “classical education”—differs profoundly from the instruction offered by modern district public schools. It is heavily oriented toward the liberal arts, guided by the Western canon, and grounded in Greek and Roman traditions of academic excellence.

While parents give good teachers and strong academics priority in evaluating a school, they also rate safety highly and consider extracurricular activities.[1] Educational philosophy or religious vocation is often highly valued as well. In a multicultural and diverse society like the U.S., every family will undoubtedly possess different values. Classical education can serve a diverse set of students and be utilized as an alternative to the education models favored by the majority of local district public schools.

This issue brief seeks to add to the discussion of educational pluralism by highlighting the history, features, and successes of the classical education model. The model is unique for its emphasis on building the student to be a scholar and an active citizen. Classical schools come in the form of private and charter schools, homeschooling, and micro-schooling. This paper will profile classical-model charter schools in New York City, Washington, DC, and Nashville. Each one has a majority-minority student body whose state test scores match or exceed their respective public school district’s average.

Classical Education: An Overview

Modern classical education is inspired by the ancient Greek and Roman traditions of art, literature, and language that are the foundation of Western civilization. During the medieval period, educators synthesized much of what endured from this tradition with the values of Christianity and established a framework to educate future generations. [2] The West’s theologians, statesmen, and philosophers were thus educated in the classical tradition.

Today, classical education is synonymous with “authoritative, traditional and enduring.” [3] The teaching of ancient Greek and Latin languages and literature endures, but the designation “classical” has been broadened to include languages and literature beyond Rome and Athens that uphold the virtue of “excellence.” Educators today define classical education as an education that teaches the best of the West.

America’s first public school was the Boston Latin School, established in 1635 with the mission of preparing students for the rigor and substance of classical education in a college setting. Mastery of Latin was a requirement. In the next century, many of the country’s Founding Fathers and other early American leaders were classically instructed—fluent in Latin and other ancient languages and well versed in classic literature. [4] Much like in the ancient and medieval periods of the West, education at any level was largely accessible only to the elite and wealthy. [5]

Public education as we understand it arose in the first half of the 19th century; the first state to mandate education was Massachusetts in 1852, and the last state to do so was Mississippi in 1918. Enrollment was not universal; according to the federal government’s National Center for Education Statistics, “roughly half of all 5- to 19-year-olds were enrolled in school” in the last half of the 19th century. Before the Civil War, “school enrollment for blacks was limited to only a small number in Northern states.” [6]

Educational institutions for blacks freed after the Civil War evolved in two distinct forms: one for industrial education, the other for the liberal arts. Notable figures such as Booker T. Washington promoted the former as the best way for black Americans to integrate into society. Aided by numerous benefactors, Washington founded a range of schools to train adolescents and young adults as masters of trades and future teachers in their communities. Notably missing from Washington’s industrial curriculum was instruction in the “dead languages.” [7]

Many activists, however, viewed a liberal arts education as the key to black Americans’ equal participation in political and social life, which would require integrating with even the college-educated elite of the time. In The Souls of Black Folk, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that engaging in the study of works by figures such as Shakespeare and Aristotle would give black individuals the knowledge to liberate themselves. [8] Thus, the first black public high school, founded in 1870 as Washington, DC’s Preparatory High School for Colored Youth (presently called Dunbar High School), was rooted in the classical tradition. [9] Segregated black high schools in the early to mid-1900s offered instruction that was heavily influenced by the liberal arts but offered both industrial and classical coursework to their students. [10]

Horace Mann, the mid-19th-century reformer who orchestrated the movement toward free public education across the country, believed that schools, while secular, should inculcate character and values in students, as well as a sense of allegiance to democracy and nationhood. [11] In the 20th century, however, educators within the Progressive movement, such as philosopher and psychologist John Dewey, believed that education should focus on present-day concerns and interactions between student and teacher for the larger purpose of encouraging democracy and social reform. Problem-solving, issue advocacy, experiential learning, and social change were at the core of progressive education. Its focus on the present made the student’s interests and desires equal to those of the teacher. [12] Thanks to the influence of Dewey and others, classrooms became more democratized but moved away from principles such as tradition, virtue, and authority.

Today, public schooling in the U.S. is influenced by many schools of thought. Some still model their curricula on ideals espoused by progressives such as Dewey. More recently, a movement toward teaching literature and history through a critical racial lens has evolved. Other schools teach in a way that downplays or ignores significant negative parts of America’s history. [13] Because public schooling in the U.S. is highly localized and democratic, no single pedagogy dominates.

Contemporary Classical Education

Today’s classical curricula can be found in homeschool environments, micro-school pods, private institutions, and public charter schools. In the religious school sector, classical education often incorporates biblical texts and training. These schools often brand themselves as classical Christian schools or classical academies and inculcate their students with a rigorous education and Judeo-Christian values. [14] Some Catholic schools have also harked back to a classical model in teaching their tradition. While not representative of most Catholic schools, some parochial schools [15] have made an effort to give parishioners the option of classical education, while some Catholic-affiliated networks [16] have also created schools to offer a classical Catholic education.

Some of the most ardent supporters of classical education are in the homeschooling and micro-schooling movements. Homeschool programs such as The Well-Trained Mind are designed to give parents the information necessary to educate their children in a classical manner. Training in spiritual faith is usually a crucial aspect of their education, as it would be in a religious school.

However, classical education is not limited to private, religious, and home schools. Several public charter schools have adopted aspects of classical learning. These schools, particularly in urban areas, are designed to give students from disadvantaged groups a stronger educational foundation and a better shot at college readiness. While jurisprudence surrounding the U.S. Constitution’s Establishment Clause prevents public charter schools from promoting the values of any particular religion, [17] many classical charter schools incorporate secular “character training” into their curricula.

Three Stages of a Classical Education

American public schools aim for grade-level readiness beginning with kindergarten and ending in the 12th grade. Medieval Roman educators employed a broader model of primary education known as the “trivium.” [18] In a liberal arts education, the trivium refers to the teaching of the first three arts: grammar, logic, and rhetoric. Though practically all classical charter schools today employ conventional grade levels, this highly language-intensive structure influences today’s classical educators, thanks to Dorothy Sayers’s 1947 essay “The Lost Tools of Learning,” which reintroduced the trivium to a modern audience. [19]

Grammar, the first stage, refers not to the rules of language, but to the youngest years of a child’s education, during which the goal is to build a foundation for future learning by establishing a knowledge base.

The logic stage builds upon the grammar stage and teaches students how to outline and evaluate arguments. During the logic stage, students consider narratives from history and English literature (and the literature of other languages), and they practice explaining the facts of the world.

In the rhetoric stage, students learn how to express their thoughts. Using the knowledge acquired during the grammar stage, as well as the tools developed during the logic stage, they learn how to make their own arguments—both written and oral. Classical learning heavily relies on the Socratic method, pitting ideas and arguments against each other in pursuit of truth. By challenging properly skilled students to explore their ideas, a classical education imbues students with a desire to seek truth in all further education after leaving school.

On the surface, a modern classical curriculum might appear similar to a typical district school education: it includes math, science, English and language arts, history, the arts, and foreign languages. But the coverage of these subjects is distinctive.

English and language arts in a classical school are split into two subjects: reading and writing. Reading receives particular attention because it is the ultimate source of knowledge in all other subjects. [20] In many classical elementary schools, literacy is the ultimate goal for students. Writing also receives great focus because the written word is the chief way ideas are expressed and disseminated in the Western tradition.

Therefore, in the grammar stage, students are expected to comprehend phonics, develop vocabulary, and learn the structure of a sentence. Many of a student’s early years are spent memorizing facts rather than developing original ideas. Toward the end of the grammar stage, exercises like diagramming sentences, writing in cursive, and writing brief expository sentences are used to ensure that students can demonstrate mastery of the foundations of the written word.

The logic stage expands students’ knowledge of language arts by teaching them to explain the “why.” Reading comprehension requires more of the student than parroting a written passage—careful analysis is essential. Students in the logic stage begin to read more challenging works that allow them to put these tools to the test. Middle school children learn the best of the Western canon, studying timeless works such as Shakespeare’s plays and novels like To Kill a Mockingbird.

In the rhetoric stage, students craft their arguments and express original ideas. Older students, having developed strong vocabularies and reading comprehension skills, graduate to more challenging works like Greek epics and 19th-century literature such as Les Misérables. Teachers in the rhetoric stage require students to critically analyze the meanings and arguments supported by a text, in addition to making arguments of their own.

A knowledge of history is regarded as the backbone of classical education because it accomplishes three objectives. First, history informs students of how we have arrived at the current moment. Second, it serves as a bulwark against arrogance, putting students’ community and country into a proper context of the vast span of global civilization. [21] Third, history provides examples of people’s and civilizations’ successes and failures, thus offering lessons to students who will be history makers in their own time.

In the grammar stage, history teaches students the basic facts of human civilizations. Young students memorize facts about various empires, leaders, wars, and movements. Such fact absorption provides students a solid foundation for eventual critical thinking and logical analysis.

In the logic stage, students begin to delve deeper, asking “why” human history developed as it did. Students may take on assignments that ask them why Napoleon failed to dominate the European continent, or why British taxes catalyzed the American Revolution. Students in classical schools often rely on primary sources rather than textbooks at this stage, in order to gain more fully the perspectives of historical figures.

Students in the rhetoric stage voice their perspectives on events and figures in history. Through essays or the use of oral methods such as Socratic dialogue, they defend or challenge historical points of contention. Students may, for example, critique or qualify the spread of Christianity throughout the Americas or debate the ethics of Communist regimes. By providing an environment in which students engage in disagreement and argumentation civilly, classical teachers help students hone their thinking skills in the pursuit of truth.

Math and science instruction is distinctive in classical curricula. As with language arts and history, math and science for students in the grammar stage are dominated by memorization of basic facts in preparation for future learning. Later stages of math and science present subjects such as calculus and physics—not unlike most district schools. However, when classical educators apply the principles of logic and rhetoric to math and science coursework, there is a broader agenda. For example, a biology teacher might organize a unit on plant domestication and discuss the evolution of agriculture and civilization. Classically educated students not only master the sciences but connect them to history and contemporary issues.

Classical schooling insists that the purpose of education is to cultivate a mind pursuant of truth. Classical schools often require coursework in Latin or Greek, music composition and practice, debate, and the visual arts. The mastery of ancient languages connects students to the ancient works they read in literature classes and the public figures they study in history. Study of the visual and performing arts grants students access to classical works and compositions, while also giving them avenues for self-expression.

Classical education demands that students strive for excellence in academics but also in areas such as self-discipline and accountability. This is why a major component of this model is often some form of ethics or character training. In the classical Christian tradition, religion classes serve this purpose. In a secular classical school, character training is often embedded within the curriculum and discipline standards, and it can be formalized in a civics course.

Ethics and character training are essential for two primary reasons. First, discipline and accountability are virtues in and of themselves, and classical education seeks to transform the whole student. Second, classical education is invested in ethics because proper character guides students on how to pursue truth. Students might question the need to study Latin or literature such as The Aeneid. “When will I need to use this?” is a common reaction to difficult or seemingly impractical lessons. But classical educators teach that virtue goes beyond mere practicality and aims to produce “a student who pursues excellence and moderation in all things.” [22]

Perhaps the most significant distinction of a classical education is its insistence that specific values matter. Attempts at value-neutrality fail to produce an environment suitable for knowledge acquisition and dialogue. [23] Education requires a shared understanding of principles and fundamentals. Classical educators profess to inculcate in their students a particular way of digesting and interpreting facts and formulating and defending their own viewpoints.

Three Classical Charter Schools

As the U.S. grows more diverse, people desiring more inclusion and multiculturalism might be wary of advancing classical education. However, critics overlook the unifying aspects of

classical education. Those engaged in the classics respect the importance of a common people having a shared language, base of knowledge, and history. Furthermore, classical educators recognize the mission of teaching many groups’ histories of the West.

The three charter schools profiled below share several features. They reflect the stages of the trivium across traditional grade levels; their demographics show that a classical education need not be culturally unresponsive and can reach students of all backgrounds; and standardized assessments of their students indicate that instruction in the classical fashion is academically rigorous and can meet contemporary expectations.

Nashville Classical Charter School

The American South has historically lagged in outcomes and opportunities for its children. The legacy of slavery—and Jim Crow laws especially—placed blacks at a profound educational disadvantage. One charter school in Nashville has a mission to teach the most disadvantaged children with a classical curriculum.

Charles Friedman founded Nashville Classical in 2011 and opened its doors in 2013. Citing lagging literacy and proficiency rates, [24] he believed that families in the Nashville area needed an alternative that could secure them the opportunities they deserved. Friedman settled on a curriculum rooted in the classical tradition after consulting with numerous families and relying on his personal experience as a Teach for America Fellow in Philadelphia.

Nashville Classical’s curriculum emphasizes the students’ shared understanding of knowledge, while also offering them information about the world. The school employs E. D. Hirsch’s Core Knowledge curriculum for its English and history classes. [25] Hirsch’s program offers a foundation of knowledge for students to become good citizens by imparting cultural wisdom by studying historical figures and enduring literature. In Nashville Classical’s English classes, students read various myths and folktales that have withstood the test of time. Its history courses deliver deep, foundational knowledge of civilizations throughout world history. In kindergarten, students learn about the lives of kings, queens, presidents, and other major leaders. In the third grade, students focus on ancient Rome and Greece.

“Curriculum should be a mirror and a window,” Friedman says. Because Nashville Classical has a diverse student body, students bring to the school numerous perspectives and cultures. Friedman believes that the curriculum ought to reflect this reality while instilling wisdom from traditions that have spanned generations. He achieves this balance by promoting the liberal arts and the Western tradition and promoting works and historical figures from diverse backgrounds. While students learn the history of ancient Rome, the Renaissance, and the Founding Fathers, they also read novels such as Esperanza Rising and The Autobiography of Frederick Douglass to gain a variety of historical perspectives.

Nashville Classical emphasizes the arts in “liberal arts.” Each student is required to take a course in music (either choir or a musical instrument) and a foreign language (Spanish or French). Beginning in kindergarten, students at Nashville Classical are exposed to the foundations of music composition and performance—both classical and contemporary—while also learning the basics of playing instruments and songwriting.

In many urban schools, behavioral disruptions have a deleterious effect on learning. Nashville Classical offers an environment that Friedman describes as “structured and intentional.” Structure helps students understand why rules are in place, and clear standards help students answer the question, “What is the reason for everything?” Uniform policies, walking through the halls together, singing songs collectively as a school, and other rituals and routines promote a sense of community. Nashville Classical holds students to high standards in order to make them excellent students. In return, the school treats students as excellent. Each classroom is named after a college or university, and students are taken on field trips to campuses.

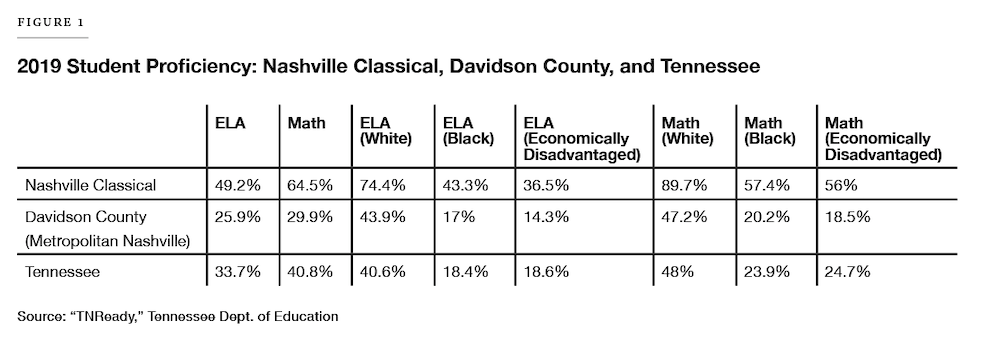

Nashville Classical posts higher rates of proficiency in ELA (English Language Arts) and math—both as a student body and by race—than district public schools. Compared with other public schools in the area, Nashville Classical more than doubles its students’ proficiency rates in math (64.5% vs. 29.9%) and nearly doubles their proficiency rates in ELA (49.2% vs. 25.9%) (Figure 1). Black students at Nashville Classical also achieve far higher rates of proficiency in ELA and math compared with their counterparts elsewhere in the school district and the state as a whole. The student body itself is majority-minority: 62% are listed as black, and 8% are listed as Hispanic [26] (the Metropolitan Nashville school district is 27% black and 10% Hispanic). [27] Given the results that Nashville Classical produces, Friedman’s goal of “[making] sure excellence is celebrated, and that excellence doesn’t have a color” has been achieved.

South Bronx Classical (SBC)

The mission of this network of four charter schools is to provide some of New York City’s most disadvantaged students with a liberal arts education. Founded by Lester Long in 2006, South Bronx Classical (SBC) is located in a poor section of the city’s poorest borough. [28]

The New York City public school system is the largest public school district in the country, serving more than a million students across five boroughs. The experiences of each student in the district vary widely by borough and by community district inside each borough. Four of New York State’s top-ranking 10 counties on the ELA and math assessments are in New York City: New York County (Manhattan), Kings County (Brooklyn), Queens County, and Richmond County (Staten Island). Bronx County is among the state’s lowest-ranked 10 counties on math assessments, and it ranks below average on ELA assessments. [29]

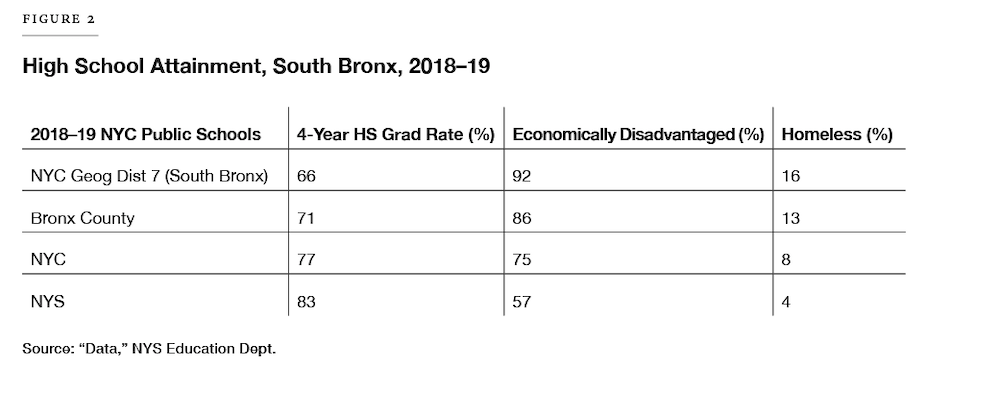

The South Bronx’s public school students are much more likely to be from economically disadvantaged communities and are more likely to experience housing insecurity than students elsewhere in the Bronx. As a result, students in this area lag in educational attainment, with high school graduation rates lower than the rest of the city and state (Figure 2).

For Lester Long, a classical education means getting back to the basics. He began his career in education as an NYC Teaching Fellow at a low-performing public school in the South Bronx. Long laments that education has been heavily theoretical and experimental since the rise of Dewey. His charter network runs on academic rigor, sequential learning, and having an adult in the room who can authoritatively help children with the necessary information for life. South Bronx Classical opened its second school in 2013, its third in 2015, and its fourth in 2017.

South Bronx Classical’s curriculum relies on a Western-focused curriculum, using foundational texts as the basis for learning. In English classes, students read classic novels such as Brave New World, 1984, and Lord of the Flies, along with a number of Shakespearean plays. Educators at SBC recognize that the U.S. has a particular history and that students within the network are mostly from minority cultures that have been overlooked in previous classical settings. Consequently, SBC has incorporated novels by writers such as James Baldwin and Toni Morrison—works that can add knowledge and wisdom to the history of the West.

Beyond core subjects, SBC relies on several curricular characteristics of classical education. Long insists on students learning Latin for three reasons. First, Latin is a gateway language to cultures around the world. Languages whose influence spans continents, such as Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese, are all rooted in Latin. Second, Long points to research showing that learning Latin correlates with higher SAT scores. [30] Third, according to Long, Latin signifies elite status. “There’s no reason these kids can’t be elite,” he says.

Students also take classes in art and music. They learn the foundations of visual art such as perspectives caused by shading and light. Students also gain practice in various media, including painting, drawing, Photoshop, and papier-mâché. An SBC student who attends kindergarten through eighth grade will take nine years of music classes, which are mandatory course requirements. Younger students at SBC begin by learning to play the recorder. By the time they are in middle school, they learn to play band or orchestral instruments, mastering compositions ranging from classical to contemporary.

SBC middle-school students take debate classes in which they sharpen their analytical skills. Long considers debate, properly practiced, a healthy style of disagreement: either one side will convince the other, or both sides will at least respectfully understand the other.

Academically, SBC stands far above schools in the surrounding South Bronx area. Each school in the network reflects nearly universal proficiency in core subjects such as ELA and math. SBC’s results not only greatly surpass neighboring schools’ but are positive outliers in New York State. SBC schools meet their mission of educating the community where they are located: 97% of SBC students are black or Hispanic, mirroring the 96% of black or brown students in the South Bronx geographic district (Figure 3). [31]

Washington Latin Public Charter School

Washington Latin was established in 2006 to provide a British-style independent education (referred to as “public school” in the U.K.) [32] to students in America’s capital city. Today, formality, uniformity, and the humanities are emphasized in its instruction, and the educational curriculum is classical. Students are not only expected to acquire knowledge but are also expected to become virtuous students and principled citizens of their community.

Washington Latin utilizes the Socratic method, allowing students to express their own reasoning but have their opinions challenged, civilly, in the common pursuit of truth. For example, in an upper-level English class, students compare and contrast the story of Odysseus with Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Oral discussions like this not only allow students to hone their craft of argumentation but also help connect lessons of the past to the present.

According to Washington Latin’s outgoing principal Diana Smith, Socratic dialogue commonly appears in humanities courses like English and history but also in STEM classes. In a chemistry class, Smith says, students may discuss the real-world implications of advancements in nuclear technology. While learning geometry, teachers may incorporate lessons of architecture, so that students might reflect on the beauty of math. Doing so intends to give students a deeper appreciation of the sciences and mathematics.

Students are required to take two years of a foreign or ancient language. Latin and Greek are featured, but French, Arabic, and Chinese are offered as well. Smith believes that it is necessary for students to study these languages because doing so connects students to the various cultures and literature that they will encounter while enrolled.

Washington Latin incorporates character and moral lessons into its school disciplinary policies. Smith notes that students learn leadership skills and conflict resolution: older students often serve as mentors and play a prominent role in conflict mediation between their younger classmates. Students actively correct behavioral deviations from school policy through the use of restorative practices. For example, Smith says, if a student throws food in the cafeteria, mentoring students will require the student to address the infraction, perhaps by cleaning the cafeteria as restitution. Students earn trust from teachers and administrators and become active participants in the cultivation of good character.

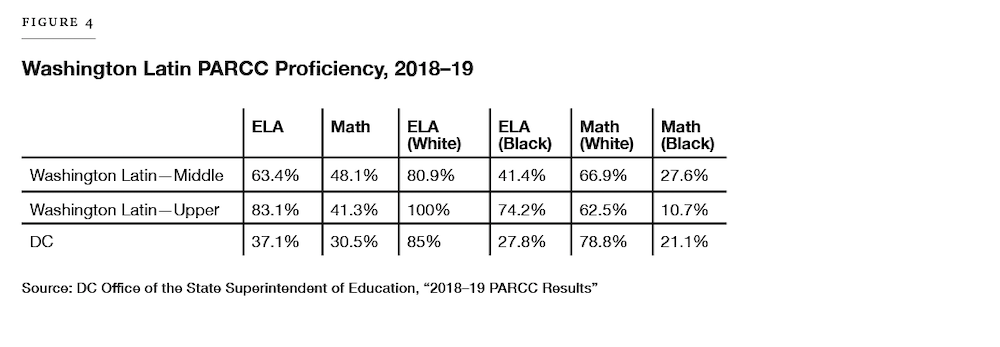

The school has a 90% four-year graduation rate, compared with DC’s 69% graduation rate in the traditional public high schools. The student body performance on the District’s standardized Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) exams [33] reflects the intensive focus that the school places on the humanities. Students in both the middle (grades 5–8) and upper (grades 9–12) schools exceed rates of proficiency in the Washington, DC, public school district on ELA assessments for black and white students. While math scores on average at Washington Latin surpass those in the general populations, they lag at the high school level.

Conclusion

Students who enter a classical school should expect to be confronted by an academically rigorous curriculum that challenges them to read texts and histories that form the basis of American society—and that of Western civilization. Additionally, a classical curriculum challenges students to become avid seekers of knowledge, ready to challenge all arguments in the pursuit of truth. Classical educators deem this ability to think critically, pursue truth, and engage in civil debate as crucial to participation in a free society.

Of course, classical education may not be for every child. Other schools may offer more programs for students gifted in areas such as technology or math, for example. However, classical schools often do an excellent job of providing a curriculum that is adaptable and suitable to students of various backgrounds and interests. Complaints by educational theorists or commentators that the classical curriculum is too rigid and resistant to the realities of the present day are not borne out by the performance of the students in the schools profiled in this paper. Classical schools—private, parent-led, and public charter—are capable of transforming students from diverse backgrounds into scholars and citizens prepared for modern problems via a knowledge base rooted in timeless traditions.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).