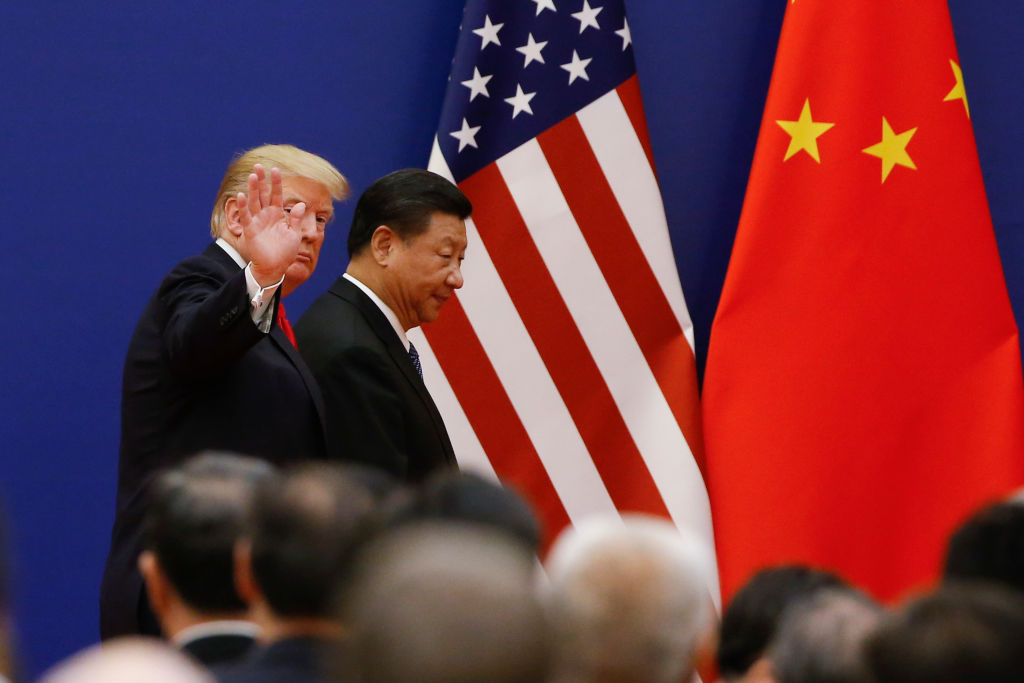

China has upped the ante in its trade dispute with America. By allowing the yuan to fall on foreign-exchange markets, Beijing has shown how far it will go in response to existing US tariffs on Chinese goods, as well as additional ones now threatened by President Trump.

But China’s moves also signal weakness: Beijing can no longer play the tit-for-tat tariff game. And because the devaluation has raised the risk of capital flight from China, the currency move also hints at desperation.

With or without the devaluation, Beijing is in a tough spot. On one side, the Communist Party can ill afford a trade war, since it has an implicit contract with the Chinese people to deliver prosperity in exchange for autocratic rule. But Beijing cannot countenance Washington’s demands that China import more from the United States, cease cyber theft and let Americans do business in China without Chinese partners.

These aren’t new demands, but the Trump White House wants them guaranteed in Chinese law. This last point, China’s leadership claims, is an affront to the country’s sovereignty — already a sensitive issue, given the turmoil in Hong Kong.

China has always held the weak economic hand in this dispute. Its export-dependent economy needs overseas sales, which comprise one-fifth of its gross domestic product. More than a quarter of those exports go to the United States, meaning 5% of China’s economy is exposed in this trade dispute. By contrast, the United States counts on exports for about 12% of its GDP, and barely 8% of its total exports go to China, leaving just 1% of the US economy exposed.

Moreover, some 30% of US goods sold in China are off limits to tariffs, as they constitute components, mostly to computer and iPhone assemblies, that support Chinese exports.

These relative disadvantages showed themselves early in the dispute. American firms began moving their operations elsewhere, while many Chinese firms have decamped to other Asian countries, in large part to avoid the American levies. Even the perennially upbeat (and suspect) official Chinese government statistics show that the economy is suffering — China’s GDP during the second quarter grew in real terms at its slowest rate since 1992.

Export volumes appear to have dropped more than 4% in the past year. Imports have also declined by more than 5%, indicating a drop in employment and consumer spending. While official figures still suggest a robust Chinese jobs market, surveys of Chinese media show a marked drop in help-wanted advertising.

These economic setbacks have also constrained China’s access to hard currencies, primarily the dollar, forcing a dramatic ebb in China’s once-mighty flow of overseas investments. In the first half of 2018, investment volumes ran at a quarter of their pace during this same period in 2017.

Long before the recent devaluation, these severe economic setbacks had already put China’s yuan under pressure. Until recently, the People’s Bank of China resisted that downward push. They did so because China needs financial capital, and in reaction to a loss of the global purchasing power of the yuan, Chinese wealth holders will send their money abroad.

The Chinese also understand that a devaluation to offset the Trump tariffs would mean that Chinese operations would receive fewer dollars for each sale; in other words, manufacturers would pay the tariffs for the American buyers. Given these risks, the Chinese currency devaluation indicates that the leadership is in a bind.

Sovereignty issues matter a great deal to the Chinese. If the Americans were to relent on this point, Beijing would sign a deal quickly. But the White House has good reasons for insisting on changes in the law. American presidents since Bill Clinton have all complained about Chinese trade practices, and Beijing has continually offered assurances that it always reneges on. Trump’s hard line is a response to this past duplicity.

The United States could have an agreement tomorrow if the White House were willing to accept China’s vague promises. But America doesn’t need to give in to the Chinese obstinacy. Even now, talks continue. China might yet succumb to economic pressure and yield to American demands — but the prospect of a deal would brighten considerably if the White House could offer Xi a means of saving face on the sovereignty issues.

This piece originally appeared at the New York Post

______________________

Milton Ezrati is a contributing editor at The National Interest, an affiliate of the Center for the Study of Human Capital at the University at Buffalo (SUNY), and chief economist for Vested, the New York-based communications firm. His latest book is Thirty Tomorrows: The Next Three Decades of Globalization, Demographics, and How We Will Live. This piece was adapted from City Journal.

This piece originally appeared in New York Post