Brain Drain Reconsidered: Toward a More Sophisticated Approach to Regional Talent

Editor's note: The following is the fifth chapter of The Next Urban Renaissance (2015) published by the Manhattan Institute.

Introduction

American cities, regions, and states try hard to increase educational attainment because education is a major driver of economic success. Such efforts focus heavily on retaining locally raised or educated talent—stopping the so-called brain drain. This is a mistake.

Why the emphasis on brain drain? Talent retention is seen as the return that justifies local investment in education. The focus on brain drain also comes from a fear that a place may be insufficiently attractive to lure outsiders. In many such places, however, few people actually leave. What’s more, out-migration can drive economic development locally—a form of human-capital development in its own right. For this reason, places with low population churn may be better off encouraging more people to leave.

Rather than focus efforts on brain drain, cities, regions, and states should engage émigrés to benefit from economic connectivity and encourage their later return home. Further, such places should be bolder and seek to attract newcomers without previous local connections.

I. Brain Drain

Data show that about 60 percent of the variation in metropolitan areas’ per-capita income is explained by college-degree attainment rates.1 Public-policy discussions about creating economic growth in cities, regions, and states—particularly those that have experienced significant decline—tend to revolve around raising a community’s number and percentage of residents with college degrees. The main focus of such efforts has been to retain educated residents. This is often expressed by a desire to stop “brain drain,”2 or the migration of educated residents away from an area.

“Halting ‘brain drain,’ or the migration of educatedresidents away from an area, has become a key part of the talent strategy for U.S. cities, regions, and states.”

Why the focus on brain drain? In part, retention is implicitly what justifies a community’s investment in education. States and cities pay lots of money to educate their children. If they leave, that educational investment appears wasted. The title of a Columbus Dispatch article on the subject—“Ohio Grads Take Diplomas and Run”3—neatly captures this view. The article quotes a local foundation official: “We need our bestand brightest to invest their energy and future in Ohio.” If grads leave Ohio, the argument runs, the state loses its return on investment.

There’s an emotional component, too. Not only is brain drain seen as an economic loss; it is viewed as a form of rejection, even betrayal. For example, when NBA star LeBron James famously left the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2010 to sign with the Miami Heat, team owner Dan Gilbert thundered: “As you now know, our former hero, who grew up in the very region that he deserted this evening, is no longer a Cleveland Cavalier.… The good news is that the ownership team and the rest of the hard-working, loyal, and driven staff over here at your hometown Cavaliers have not betrayed you nor NEVER will betray you.... This shocking act of disloyalty from our home grown ‘chosen one’ sends the exact opposite lesson of what we would want our children to learn. And ‘who’ we would want them to grow-up to become.”4

II. How to Think—and Act—About Brain Drain

Halting brain drain has become a key part of the talent strategy for cities, regions, and states. There are no comprehensive spending statistics available on anti–brain drain initiatives. In some cases, the “stopping brain drain” label is applied to projects with other, hidden motivations, such as subsidizing professional sports teams or well-connected developers. Yet it is easy to find anxiety about brain drain almost everywhere—in some of America’s most successful places, as well as in distressed areas.

One notable case is Michigan, where former governor Jennifer Granholm created a project, “Cool Cities,” to apply the theories of economist Richard Florida to reverse brain drain in the Wolverine State. The initial Cool Cities report stated: “At the ‘State of the State’ address, Governor Granholm made it known to all of Michigan that her administration would pursue an initiative to create ‘Cool Cities’ throughout the state, in part as an urban strategy to revitalize communities, build community spirit, and most importantly, retain our ‘knowledge workers’ who were departing Michigan in alarming numbers.”5

In Indiana, many studies have also sounded the alarm about brain drain. One study by the Indiana Fiscal Policy Institute found that Indiana retains 30 percent fewer college grads than other states.6 Since 2000, organizations in the state have spent nine figures on various brain-drain initiatives, much of it in the form of grants to universities.

In Ohio, Eric Fingerhut, former chancellor of the University System of Ohio, set retention as one of his personal success metrics: “ ‘But this,’ he said, pointing to the next objective, ‘Keeping graduates in Ohio,’ ‘this is all new to higher education. Isn’t this the mayor’s job, the chamber of commerce’s job? No, it’s our job, and we have ways to do this.’ Fingerhut promises to persuade 70 percent of graduates to stay in Ohio—roughly the same percentage that now leaves. ‘We own this metric now, and that’s a radical departure,’ he said.”7

Chicago, the city that the rest of the Midwest most worries about losing its brains to, also worries about brain drain, particularly the loss of tech talent to Silicon Valley. Crain’s Chicago Business quoted Mayor Rahm Emanuel discussing the people “who made their start in Illinois, but made their reputations and fortunes in Silicon Valley,” as he announced a major push to create tech jobs locally to retain talent.8 In 2014, the website Curbed worried that the harsh winter “polar vortex” was causing a brain drain from Chicago.9 In 2003, the Boston Chamber of Commerce commissioned the Boston Consulting Group to create a study, “Preventing a Brain Drain: Talent Retention in Greater Boston.”10 These are just some of the ways in which states and cities think about and respond to the idea of brain drain.

III. Brain Drain—A Defeatist Mind-Set Rooted in Fear

At its heart, brain drain is a concept inspired by the fear of losing what communities tend to emotionally value most: their children and young people. Brain drain ignores gains and thinks only of losses, assuming a zero-sum worldview.

A trope of the motivational industry is to ask, “Do you have a scarcity mentality or an abundance mentality?”11 Fear of brain drain derives from a scarcity mind-set. Because of its obsession with losing locals, brain drain implies that a city or state cannot attract residents who were not born there or did not attend school there. That place’s current talent base is all it has, the argument goes, and therefore the only way to grow human capital is to educate and retain people who reside there.

The belief that only native residents could possibly choose a particular city or state to live in is a sign of a community that has lost faith in itself. By contrast, while America’s talent hubs also fret about brain drain (anxiety about retention is universal), they are confident in their ability to attract global talent. Silicon Valley was not built on retaining the graduates of Palo Alto High School. Yes, local institutions such as Stanford play a key role in the tech industry; but Bay Area talent is sourced, overwhelmingly, from the global, not the local, best and brightest.

Such places know that an important factor in evaluating a business opportunity is market size: How big is the target market? Applying this to talent, brain drain focuses resources on a comparatively small market: the local one. Metro Buffalo, for example, has a population of about 1.1 million,12 while the U.S. population is 316 million. In other words, Buffalo’s local market is only 0.35 percent of the national one, to say nothing of the global market. Communities obsessed with brain draintarget their small-pond market; those with more self-confidence target a much larger potential talent base.

When a community fails to believe in itself and falls prey to fear, it begins to behave not only defensively or irrationally, but perversely.

Consider Indiana University’s School of Medicine, which is proposing to build a full medical campus in Evansville. This would enable students to become fully trained physicians without having to study or complete a residency in Indianapolis, by far the state’s biggest city. From birth to board-certified doctor, a local kid would never have to leave Evansville. State Representative Holli Sullivan approves: “The campus will help control the ‘brain drain’ in keeping physicians in the South- western Indiana area and in the state.”13 Adds Sullivan, “I will do my best as a representative from my district to be a key player in making sure that we really focus on how this is really important for our whole state as far as physician retention.”

Thus it is that a university—an institution chartered with expanding young people’s minds and opportunities—becomes complicit in a plan to circumscribe the possibilities of Evansville’s children by trying to ensure that they never discover the world beyond their hometown.

What futures are curtailed in the name of stopping brain drain? The tragedy of Rust Belt places like Evansville is not that they failed but that they have too often succeeded in their quest—to the detriment of community and individuals alike. In many cases, as Section IV will show, the places that fret most about brain drain are not losing people and are actually gaining college graduates.

IV. Shrinking Cities Have Low Out-Migration and Are Gaining Brains

This brings us to the biggest problem with brain drain: it often is not real, especially in urban areas. Brain drain is frequently assumed, not demonstrated—or demonstrated with metrics that tell an incomplete story.

Consider Buffalo. The population of metropolitan Buffalo dropped by 3 percent, or 35,000 people, between 2000 and 2013.14 Over that period, the region ranked a dismal 49th for percentage population growth among the 52 largest U.S. metro areas (those with morethan a million residents). Only Detroit, Cleveland, and New Orleans performed worse. Since 2010, Buffalo has lost 1,200 residents and is 51st in population growth among large metro areas,15 with net domestic migration of –8,500.16

The conventional narrative suggests that Buffalo’s population is falling because people—especially the young and educated—are voting with their feet and fleeing a failing region. But according to my analysis of IRS data, Buffalo has one of the lowest out-migration rates in the U.S.: 20.91 per 1,000 residents in 2011, for example (50th among large metro areas).17 This rate has been low since at least the mid-1990s.

Buffalo’s problem is not that many people are leaving (they aren’t). It is that even fewer are coming. In 2011, Metro Buffalo’s in-migration rate was 17.68—again, third from bottom. While the IRS data cannot be analyzed exclusively for college graduates, Census Bureau data confirm that Buffalo has low out-and in-migration of educated residents. Even cities such as Memphis and Birmingham, hardly renowned as global-talent magnets, attract significantly more college graduates than Buffalo.

With both low out-and in-migration, Buffalo has the highest share of born-and-bred residents, 81.7 percent, of all large U.S. metro areas.18 Far from losing brains, Buffalo is gaining them: from 2000–13, the number of Buffalo residents holding a bachelor’s degree, or higher, increased by more than 53,000, a nearly 7-percentage-point increase. Indeed, over this period, Buffalo placed seventh among large metro areas in its percentage-point increase in college-degree attainment.19 All this suggests that Buffalo enjoys excellent retention.

This, too, may explain why, although its headline performance in population and job growth is weak, Buffalo’s per-capita GDP has increased by 15.9 percent since 2001—again, seventh-best among large U.S. metro areas.20 Buffalo, in other words, has experienced an increase in human-capital growth without population growth. Buffalo does face serious demographic and economic challenges; but traditional measures of health, such as population growth and net migration, tell only part of the story. If Buffalo tried to address its problems by emphasizing brain drain, the city would be missing the point.

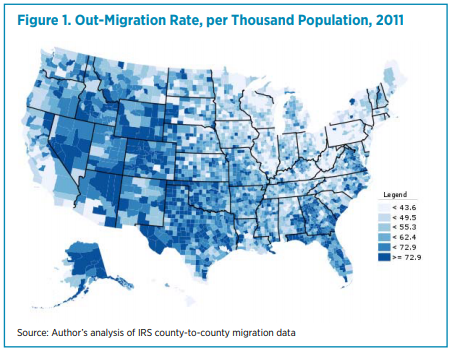

Figure 1 reveals 2011 out-migration rates for all U.S. counties. It shows significant complexity in the migration story. Certain states considered successful, such as Texas, Colorado, and Georgia, experience high out-migration. The lowest rates of out-migration are found in a band running across Appalachia into western New York (including Buffalo) and the Rust Belt.

In underperforming cities, regions, and states, too little out-migration may thus be a bigger problem than too much. With limited outflow and even less inflow, such areas have become what geographer Jim Russell calls “cul-de-sacs of globalization,” cut off from the demographic and economic flows that power development.21

V. Exporting Talent Can Stimulate Economic Growth

To some degree, brain drain may stimulate local economic devel- opment. AnnaLee Saxenian of the University of California, Berkeley, has written extensively about what she terms the “New Argonauts,”22

immigrants from places such as India and Taiwan who became successful in Silicon Valley’s tech industry, and then returned home to become key players in establishing their countries’ own tech industries. Saxenian observes: “Developing economies typically have two major handicaps: they are remote from the sources of leading-edge technology and dis- tant from developed markets and the interactions with users that are crucial for innovation.... As foreign-born, but U.S.-trained engineers transfer know-how and market information to their countries of origin, and help jump-start local entrepreneurship, they are allowing their home economies to participate in the information-technology revolution.” Migration allows individuals to acquire expertise and establishnetworks to the global economy. “Brain circulation,” Saxenian suggests, is a more accurate description of the phenomenon.

“Brain drain obscures the fact that the ‘brain’ that was ‘lost’ may never have existed in the first place without leaving the community: the act of migrating enabled the development of human capital.”

One such example involves Lisbon’s booming call-center industry, where companies such as Teleperformance have added thousands of jobs in recent years,

despite Portugal’s struggling economy. Teleperformance CEO João Cardoso attributes his company’s success partly to an exodus from Portugal, noting: “In the 1960s, we experienced huge waves of people emigrating to Germany and France. But a large number of people have returned. As a result, we have a lot of people who speak German and French at a native level.”23 Portugal, in other words, benefited from the skills and experience acquired by Portuguese émigrés.

Or consider President Obama’s executive amnesty for millions of illegal immigrants, many Mexican. Did Mexican president Nieto react angrily, denouncing the U.S. for stealing away his country’s citizens by illegal means? Not at all. Instead, he called the move “very intelligent.”24 Nieto understands that, for the aforementioned reasons, Mexicans moving to the U.S. is good for Mexico. Similarly, Brazil created a program, Science Without Borders, to send 200,000 students abroad to study in STEM fields. To date, Brazil has spent $2 billion on the program.25

Such wisdom is frequently ignored in the United States. One rea- son that Buffalo, Cleveland, and other Rust Belt cities have struggled economically is that they have been cut off from information flows and expertise that are a product of migration. Such places certainly have too little in-migration—and, perhaps, insufficient out-migration. (Note, again, metro Buffalo’s 81.7 percent share of residents born in New York State.) Rather than fight brain drain, a better strategy may be to encourage more of it: to decrease insularity and to better connect to global knowledge and economic networks.

One American city attempting to apply these international lessons is Cleveland, where Cleveland State University established the Center for Population Dynamics, inspired by a 2013 paper, “From Balkanized Cleveland to Globalized Cleveland,”26 which articulated the following theory of change:

Cleveland didn’t decline because industry left. Cleveland didn’t decline because people left. Vacant houses are not Cleveland’s cross to bear. Cleveland’s ultimate problem is that it is cut off from the global flow of people and ideas. Cleveland needs to be more tapped into the world.... Often, Cleveland’s interconnectivity is weaved as thus: college graduates hailing from Greater Cleveland move to global city and experience neighborhoods filled with outsiders. A successful global city network is one of weak ties and openness to people living outside of the community. This environment socializes Cleveland expatriates for knowledge transfer, as well as inter-regional and international trade. Think of an act of migrtion, then, as a laying down of human “fiber optics” that connect two points in space.... Upon repatriation to Cleveland, return migrants bring with them this social orientation that opens up certain neighborhoods to globalization. The neigh- borhood’s evolving interconnectedness makes the area more attractive to outsiders who have no connection to Cleveland, pulling more globally-connected citizens—be they native newcomers or the foreign born—into the city.

VI. Migration: A Key Form of Human-Capital Development

Given the well-known link between education and income, people rightly focus on education when thinking of human-capital development. And everyone understands that people often move in order to access superior economic opportunities elsewhere. But fewer appreciate that migration is a key form of human-capital development in its own right.

My personal story is instructive. I grew up a few miles outside Laco- nia, a rural town in southern Indiana (a 45-minute drive from Louisville, Kentucky) with a population of 50. At 18, I left home for university and never returned. I am now a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

It would be easy to see me as the living embodiment of brain drain. However, had I returned to my hometown, even after earning a degree, what would my professional value be today? Most of my skills and expertise, as well as my global network of connections, were acquired by virtue of my life and work outside Indiana. Had I stayed in southern Indiana, or even nearby in small, urban Louisville (a region similar in size to metro Buffalo), my professional potential would have been stunted, just as it would have been had I not attended university.

Brain drain obscures the fact that the “brain” that was “lost” may never have existed in the first place without leaving the community: the act of migrating enabled the development of my human capital.

In 2014, One Southern Indiana, a regional chamber of commerce near Laconia, retained me to do an economic development study of the area. In early 2015, I was the keynote speaker at Governing magazine’s “Summit on Performance and Innovation,” hosted by the mayor of Louisville. While there, I also spoke to the Louisville chapter of the Urban Land Institute and to a conference on rural economic development in southern Indiana. What is the likelihood that I would have been selected to give any of these talks, had I stayed locally (or, if somehow selected, what is the likelihood that I would have had much insight to contribute)? Very low.

Skills acquired via migration can later be repatriated and made available to sending regions, through return migration and by expertise provided from outside. (After four seasons in Miami—which included four consecutive NBA Finals appearances, two championships, and two league MVP awards—LeBron James returned, via free agency, to his hometown Cavaliers for the 2014–15 season.)27 Exporting talent may often be more valuable to the sending community, not less.

VII. What Human-Capital Policies and Initiatives?

In developing policies and initiatives rooted in a more robust view of talent, the first step is to take a life-cycle view of human-capital development that incorporates an understanding that out-migration is natural for a certain percentage of natives. The next step: profit from out-migration.

“The successful out-migration stories of Taiwan, India, and many other countries suggest that the benefits of wiser thinking about talent, and talent export, hold significant upside.”

How universities and professional-services firms view their alumni may be instructive. These organizations understand that their alumni

networks are one of their most important assets. How might a city, region, or state do the same? Start with finding ways to stay civically engaged with people who leave. At present, this is rarely done beyond existing personal networks, such as family. Former Boston mayor Tom Menino observed: “Every university inthe world promotes itself through the personal relationships of the people who studied there. But to my knowledge, no city in the world has ever attempted to create the same kind of massive, information-sharing community on behalf of a city.”28 In 2009, Menino launched Boston World Partnerships to attempt this, though the organization was shuttered after only three years.29

A more successful, focused effort was developed in Indianapolis. IndyXmas,30 an annual holiday party hosted by TechPoint, the city’s technology industry consortium, targets expatriates who are in town visiting family for the holidays. Hosted at a local co-working space, attendees mix and mingle with local tech firms and workers, with the goal of having fun, building relationships, showcasing growth in the local tech industry, and, the city hopes, persuading people to move back to Indianapolis to work.

Louisville has staged out-of-town events to showcase the city to expatriates. Using IRS data, a University of Louisville researcher under- took a migration analysis to determine which cities were popular destinations for out-migrating Louisvillians. The mayor and local businesses then hosted “Louisville Reunion” events in cities such as Tampa—fea- turing Kentucky products, such as bourbon31—with attendees pitched on moving back to Louisville.

These events were targeted at former residents; other cities have taken a more aggressive marketing approach, attempting to lure people with loose or no affiliation. Chicago created its Think Chicago32 event in conjunction with marquee local events, such as Chicago Ideas Week and Lollapalooza. The city invites top technology students from around the country for three days to be immersed in the city’s tech scene and attend the associated showcase event, where Mayor Emanuel personally pitches visiting students to build their careers in Chicago, instead of Silicon Valley or elsewhere.

In Las Vegas, Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh received enormous positive press for his “Downtown Project,”33 aimed at reinventing the city’s bleak downtown. This overflowing press coverage resulted, in part, from Hsieh’s unique marketing approach, which included setting aside a block of apartments in a downtown high-rise for attendees to use as “crash pads” (effectively free hotel rooms for invitees to see what he was doing).34

Realizing that many people enjoy visiting Las Vegas but do not necessarily want to live there, Hsieh also developed and pitched an idea called “subscribe to Las Vegas,”35 to persuade such people to have a part-time presence in downtown Las Vegas. While the Downtown Project has since largely floundered—partly because its goal was unrealistic— Hsieh was successful in generating enormous publicity for his project, including getting many people who otherwise never would have given downtown Las Vegas a second thought.

There are many other ways to market cities, regions, and states and leverage civic-diaspora networks. Again, much as universities and professional-services firms proactively stay in contact with alumni, such places should do the same. This can be as simple as a low-volume e-mail list.

Domestic expatriates can organize local clubs tied to their native city, such as Detroit Nation.36 Such groups could be used to notify members of hometown news, job openings, and upcoming events. Mayors and governors routinely travel out of state to speak at events, attend fund-raisers, and meet with businesses. On such already scheduled trips, they could set aside time for informal recep- tions with former residents, with priority given to key global hubs like New York and the Bay Area.

Given that diaspora networks play a vital role in facilitating access to global knowledge networks, the destinations of out-migrants matter. High schools should ensure that their students consider colleges situated in the recruiting sights of firms based in those same global hubs. Indiana, for instance, already sends lots of residents to midwestern schools, who then get drawn into Chicago’s workforce. Indiana would benefit from more connectivity to coastal markets, beginning with local students going to universities where coastal firms recruit.

Conclusion

The place-based development paradigm is widely established. The development of policies that take a more sophisticated view of human capital is in its infancy. These are some early efforts and ideas, but the field is ripe for innovation and development. The successful out-migration stories of Taiwan, India, and many other countries suggest that the benefits of wiser thinking about talent, and talent export, hold significant upside. U.S. cities, regions, and states that get it right—and get there first—may set themselves apart in the marketplace.

Endnotes

1. See https://cityobservatory.org/talent-and-prosperity.

2. According to the OECD, the term was coined by the Royal Society to describe the exodus of U.K. scientists to the U.S. in the early 1960s. See https://www.oecdobserver.org/ news/archivestory.php/aid/673/The_brain_drain:_Old_myths,_new_realities.html. Brain drain draws 4 million hits on Google and has its own Merriam-Webster entry (“The de- parture of educated or professional people from one country, economic sector, or field for another usually for better pay or living conditions”), https://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/brain%20drain.

3. See https://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2009/06/16/brain_drain.ART_ ART_06-16-09_A1_MLE6N0F.html.

4. See https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/07/08/dan-gilbert-letter-lebron_n_640318. html.

5. “Michigan Cool Cities Initial Report,” Office of the Governor, State of Michigan, December 23, 2003.

6. See https://www.purdue.edu/uns/html3month/2004/0407.Persp.braindrain.html.

7. See https://highereducation.org/crosstalk/ctbook/pdfbook/OhioBrainDrainBookLa.... pdf.

8. See https://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20131105/BLOGS11/131109934/how-chi- cagos-tech-brain-drain-might-be-slowed-reversed.

9. See https://chicago.curbed.com/archives/2014/12/19/is-the-polar-vortex-behind... go-brain-drain.php.

10. See https://bostonchamber.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/2003-brain-drain.pdf.

11. E.g., Stephen Covey said that an abundance mind-set was one of three necessary attri- butes for implementing principle four: “think win/win.” See https://www.stephencov- ey.com/7habits/7habits-habit4.php.

12. Census population estimates, 2013.

13. See https://www.courierpress.com/news/politics/medical-school-funding-tops-li... local-lawmakers_73975535.

14. Census population estimates, latest revised estimates for 2000s (updated to reflect 2010 census results) and vintage 2013 population estimate release, rounded.

15. Census, vintage 2013 population estimates, rounded.

16. Census, vintage 2013 population estimates, components of population change, rounded.

17. Unless otherwise specified, all migration information is based on IRS county-to-county migration data, as analyzed by the author.

18. Census, American Community Survey, table B05002, 2013 one-year survey.

19. Census 2000, SF3, table P37; and American Community Survey, table B15002, 2013 one-year survey.

20. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Accounts.

21. See https://www.psmag.com/books-and-culture/bright-flight-silicon-valley-78442.

22. See https://people.ischool.berkeley.edu/~anno/Papers/IMF_World_Bank_paper.pdf.

23. See https://www.dw.de/lisbon-call-center-boom-draws-eu-guest-workers/a-18269637.

24. See https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2015/jan/6/pena-nieto-of- fers-obama-help-amnesty-documents/?page=all.

25. See https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/12/when-brazil-sends-i... dents-abroad-everyone-wins/383466.

26. See https://www.urbanophile.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/From%20Balkan- ized%20Cleveland%20to%20Global%20Cleveland%20A%20White%20Paper.pdf.

27. See https://www.si.com/nba/2014/07/11/lebron-james-cleveland-cavaliers.

28. See https://www.urbanophile.com/2009/01/06/urban-alumni-networks.

29. See https://commonwealthmagazine.org/uncategorized/017-boston-world-partner- ships-calls-it-quits.

30. See https://www.wthr.com/story/27601164/consortium-hosting-party-to-show-off-... ys-tech-skills?clienttype=generic&mobilecgbypass.

31. See https://www.tampabay.com/news/business/economicdevelopment/louisville.

32. See https://www.thinkchicago.net.

33. See https://www.downtownproject.com.

34. I was one of the people who received a personal invitation from Hsieh to take advan- tage of this.

35. See https://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2014-12-30/zappos-ceo-tony-hsie- hs-las-vegas-startup-paradise.

36. See https://www.detroitnews.com/story/opinion/2014/10/16/letter-detroit-natio... nects-expats/17321981.