Systems Under Strain: Deinstitutionalization in New York State and City

In the 1950s, public mental health-care systems in New York and across the U.S. began shifting focus from inpatient to outpatient modes of treatment, a process often referred to as “deinstitutionalization.” Much of the public is familiar with its basic outlines. What’s less well known is that, in some jurisdictions, deinstitutionalization is an ongoing process.

Under the “Transformation Plan” for New York State’s Office of Mental Health (OMH), Governor Andrew Cuomo’s administration has been working to reduce both the average daily census and the total number of beds in state psychiatric centers. In the words of the Cuomo administration, by “reduc[ing] the need for unnecessary inpatient hospitalizations” and relying more on outpatient mental health services provided in a community setting, the Transformation Plan is designed to achieve the “better care, better health and better lives for those whom we serve—at lower costs.”[1]

In New York and elsewhere, many past deinstitutionalization initiatives were criticized for poor planning and execution. Cognizant of this history, and the risks involved with trying to treat serious mental illness in a community setting, OMH has tracked the progress of the Transformation Plan. Regularly issued reports have documented how much state government has invested in housing and other programs in recent years as public psychiatric centers’ bed count has declined.

But investment in community services—while necessary to address untreated serious mental illness—is not a sufficient measure of success. To gauge whether the Transformation Plan has been successful, it’s important to examine the experience of other service systems that are also responsible for the mentally ill, to determine how they have fared. This report focuses on New York City and its related service systems: criminal justice, homeless services, and city hospitals.

- Non-forensic state psychiatric centers in New York City lost about 15% of their total adult bed capacity during 2014–18, while the average daily census declined by about 12%.

- During 2015–17, the number of seriously mentally ill homeless New Yorkers increased by about 2,200, or 22%. In response, city government opened six new dedicated mental health shelters between Fiscal Year (FY) 2014 and FY 2018.

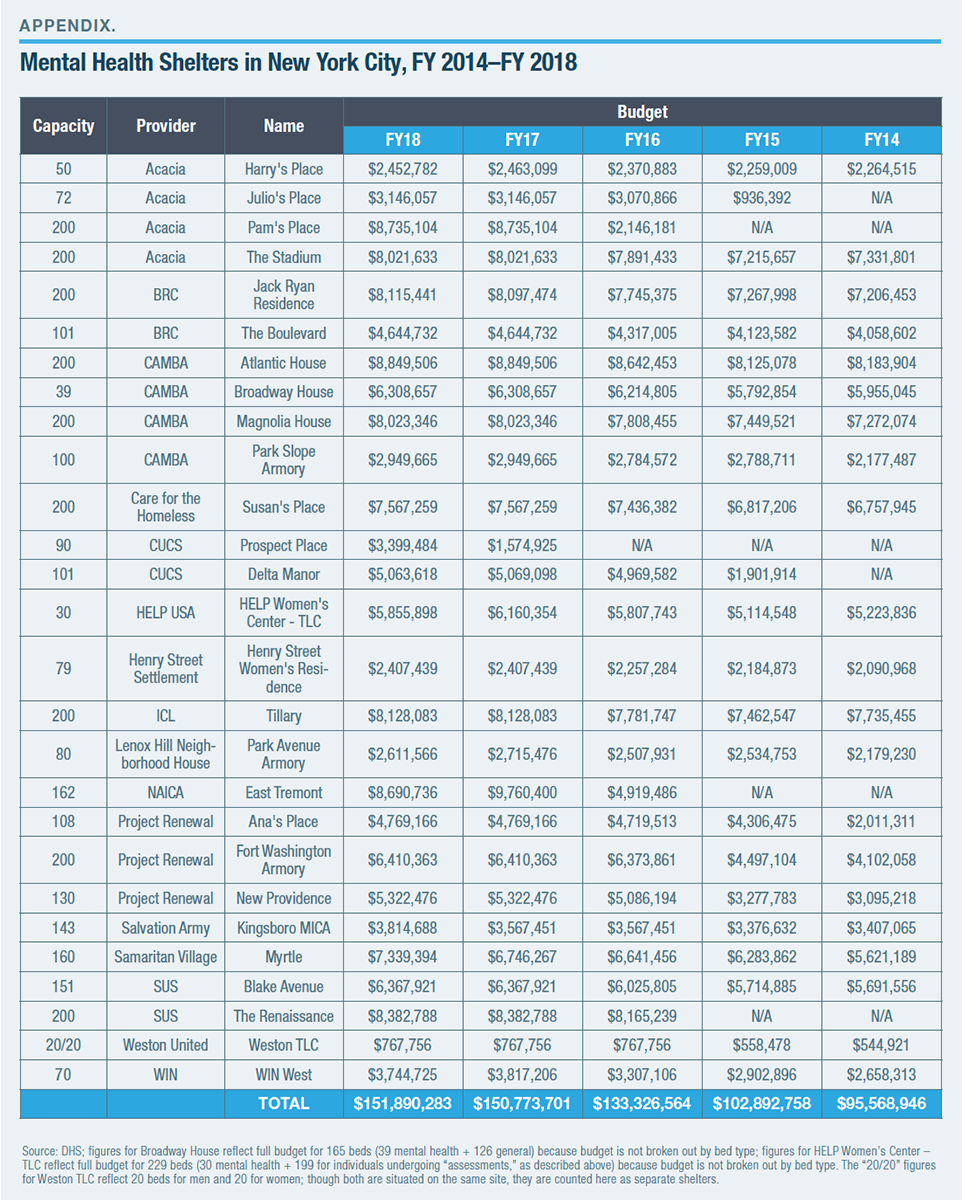

- Spending on such shelters, which numbered 28 as of the end of FY 2018, has grown every year since FY 2014 and currently stands at about $150 million. There are more beds in mental health shelters in New York City than the combined total of adult beds in state psychiatric centers and psychiatric beds in NYC Health + Hospitals facilities.

- The number of “emotionally disturbed person” calls responded to by the New York City Police Department has risen every year since 2014. The number of seriously mentally ill inmates in New York City jails is now higher than in 2014.

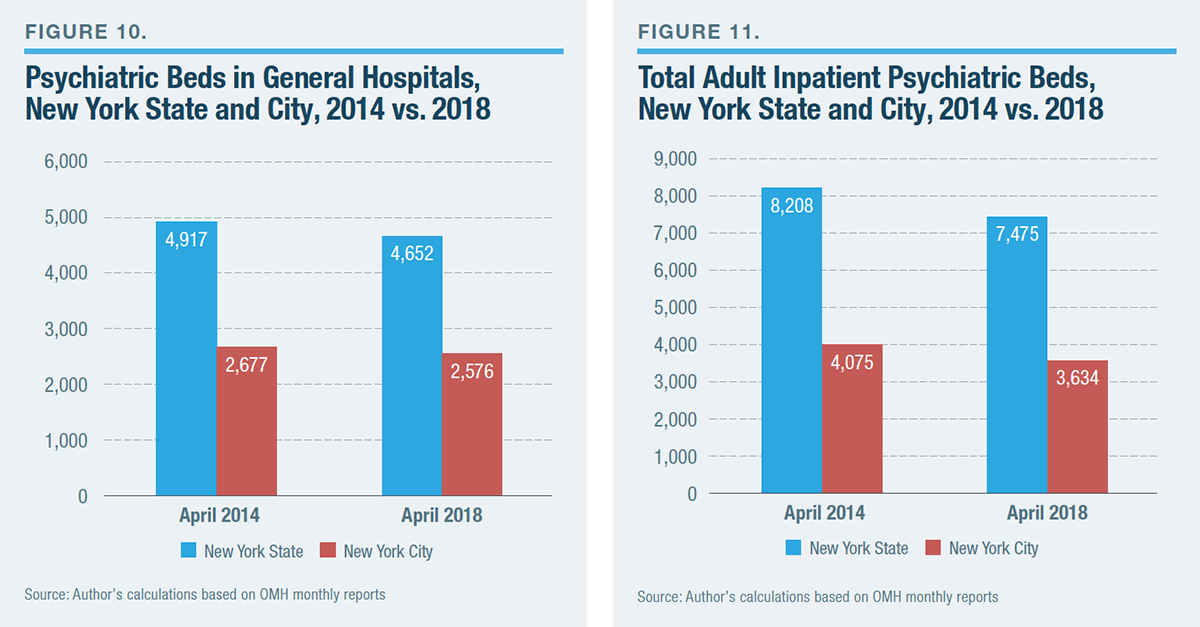

- Both state- and citywide, more psychiatric-care beds are located in general hospitals than in the traditional network of state psychiatric centers. But due to the financial pressures that many general hospitals face, they are unlikely to expand their systems of inpatient psychiatric care, and some have already reduced capacity.

Thus, as New York State has cut its inpatient psychiatric bed count, pressures have increased at the local level while the promise of better treatment at a lower cost has yet to be fulfilled. These findings cast doubt on the prudence of reducing inpatient mental health care at a time when untreated serious mental illness—a problem for which state beds are one of the essential resources—is not under control.

The Decline of New York's Inpatient Mental Health-Care System

In 2017, the most recent year for which survey data are available, 139,403 seriously mentally ill adults statewide and 72,363 in the New York City region were served by public mental health programs.[2] These numbers represent small fractions of the total seriously mentally ill adults in the state and city (865,000 and 239,000, respectively).[3]

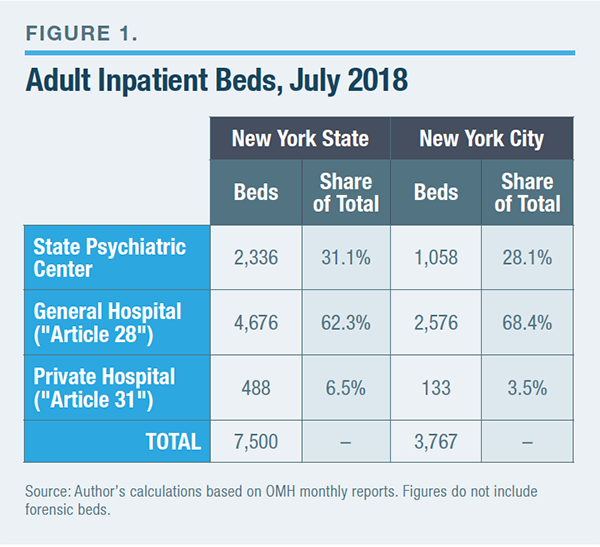

New York State’s public mental health-care system comprises thousands of programs that are directly operated by the Office of Mental Health (OMH) or are regulated by it.[4] The annual cost, including the many locally operated and funded programs, is over $6.5 billion.[5] Half of that amount funds inpatient mental health care.[6] Inpatient mental health care is provided mainly through 24 state psychiatric centers—nine of which serve exclusively children or adults involved with the criminal-justice system (“forensic” facilities)[7]—which are run directly by OMH; and about 100 programs run by general hospitals, such as Bellevue (operated by NYC Health + Hospitals, a city agency) and New York Presbyterian (a nonprofit hospital). A small number of inpatient psychiatric-care programs are run by “Article 31” private hospitals, such as Gracie Square on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, which are exclusively licensed to provide behavioral health care.

Over the decades, New York’s inpatient mental health-care system has experienced major changes. First, it is dramatically smaller than it once was. At present, the total adult inpatient census in the state psychiatric network, excluding forensic cases, numbers 2,267; in 1955, it numbered 93,314.[8] This trend parallels trends nationwide: according to the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, about 38,000 patients are in inpatient public psychiatric hospitals in the U.S., down from 559,000 in 1955.[9] As noted, the shift to an outpatient-oriented approach to the treatment of mental illness from the inpatient-oriented system that existed before the 1950s is often referred to as “deinstitutionalization.”

As America’s most populous state from 1810 to 1970 and one with a traditionally robust commitment to social programs, New York’s inpatient mental health-care system has long been substantial, constituting 17% of the nation’s total beds at the peak of the pre-deinstitutionalization era.[10] Pilgrim State Hospital on Long Island (now the Pilgrim Psychiatric Center) was the country’s largest when it opened in the 1930s, and would reach a census of nearly 14,000 patients at its peak.[11] Decades ago, it was common for patients of state mental institutions to remain there for years, and even decades. At present, though, New York’s 15 state psychiatric centers for non-forensic adult patients are home to only 1,203 “long stay” cases who have been hospitalized for a year or more, with 529 in New York City.[12]

In New York and across the U.S., state governments’ shift away from massive mental institutions was intended to provide improved outpatient treatment. In the early 1980s, state mental health agencies spent one-third of their budgets on community services; now that figure is about three-fourths.[13] Between 1986 and 2014, when measured as a share of total mental health expenditures, inpatient care declined from 41% to 16% of the budgets of state mental health agencies.[14]

Over the years, many new services and programs were developed to connect the mentally ill with treatment while they lived in a noninstitutional setting. Examples include community mental health centers, supportive housing, assertive community treatment, and assisted outpatient treatment. On the campuses of state psychiatric centers, hundreds of beds formerly classified as inpatient have been converted into residential treatment beds. Mentally ill individuals are still living on the campus and receiving treatment but are free to go as they please.[15]

The use of civil commitment to involuntarily place individuals into an inpatient psychiatric treatment program is regulated by state law. New York is regarded as having one of the strictest civil commitment standards of any state.[16] In accordance with the 1999 U.S. Supreme Court decision Olmstead v. L.C., the state is legally required to treat mentally ill individuals in the “least restrictive” setting.[17]

The inpatient mental health-care system in New York has changed in character over the decades, in addition to being smaller. General hospitals are much more important providers of inpatient psychiatric care than they were in the 1950s.[18] Throughout the second half of the 20th century, psychiatric bed counts in general hospitals and state psychiatric centers moved on different trajectories. Between 1970 and 1998, a period during which traditional state mental institutions shed tens of thousands of beds, general hospitals gained thousands of psychiatric-care beds.[19] Nationwide, general hospitals now account for about a third of all psychiatric beds; the proportion is even higher for adult beds in New York (Figure 1).[20] In New York State, the roughly 100 “Article 28” facilities (general hospitals) operate 4,676 beds, compared with 2,336 beds in state-operated adult psychiatric centers.[21]

Why New York's Inpatient Mental Health System Is Still Declining

Surveys of psychiatric bed counts nationwide have consistently found that, while New York’s inpatient mental health-care system is smaller than it once was, it remains robust compared with the rest of the U.S.[22] A 2017 survey of mental health treatment facilities by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) found that New York was one of only 10 states with at least 10 public psychiatric hospitals and one of only four with 50 or more general hospitals with psychiatric units.[23]

A 2017 report by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors estimated that New York was home to 55.3 total psychiatric inpatient beds per 100,000 population, the third-highest in the U.S.[24] A 2016 report by the Treatment Advocacy Center that focused on state psychiatric hospital beds per 100,000 population found that New York ranked eighth in the nation.[25] An analysis of 2015 data by researchers affiliated with the University of Southern California’s Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics found that New York tends to hospitalize more mentally ill individuals—and for longer—than most other states.[26]

New York’s above-average commitment to inpatient mental health care does not appear to come at the expense of its commitment to outpatient mental health care. New York ranks higher than almost every other state in measures of spending on outpatient mental health services and mental health care in general.[27] Data maintained by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development show that New York State has more permanent supportive housing units, on a per-capita basis, than any other state.[28] New York City offers one of America’s most robust networks of alternatives to incarceration,[29] which divert low-level offenders from jail and into treatment in the community. The state’s Kendra’s Law program—assisted outpatient treatment that places mentally ill individuals with a history of noncompliance with treatment into a court-ordered treatment program—is widely regarded as the most effective program of its kind in the U.S.

Though coverage is uneven throughout the state, New York boasts a higher concentration of mental health professionals than other states.[30] Total mental health treatment facilities, as surveyed in the 2017 SAMHSA report, numbered 843, second only to California. On a per-capita basis, SAMHSA data show that New York is home to 2.4 outpatient mental health facilities per 100,000 population, ninth-highest among states.[31] A 2017 analysis by E. Fuller Torrey and the Manhattan Institute’s D. J. Jaffe found that spending on mental health-care programs represents a larger share of New York’s budget than that of all but three states.[32]

But what some mental health advocates view as an asset—an above-average count of psychiatric-care beds per capita, by national standards—the Cuomo administration views as a liability. Accordingly, OMH has been working to reduce the use of inpatient mental health care by trimming bed counts and the average daily census (Figures 2 and 3).[33] The inpatient census in state psychiatric centers for adults in New York State, already more than 90% below its peak in the 1950s, dropped by 368 (14%) between 2014 and 2018. In New York City, the decline has been 138 (12%). Budgeted capacity statewide has declined by 531, or 19% (for the state), and 183, or 15% (for the city), during the same span.

What OMH terms its “Transformation Plan” began to be implemented in FY 2015.[34] Initially, the Cuomo administration had proposed closing certain state facilities, but it backtracked in the face of political opposition.[35] OMH’s plan is focused on state-run psychiatric centers, which serve only 1% of all beneficiaries of public mental health services but account for 20% of all expenditures in the system.[36] (The situation with general hospitals, which are not directly affected by the Transformation Plan, is discussed below.)

Pressures on Other Service Systems

OMH releases monthly reports that document spending on outpatient services and explain the cost and nature of its expenditures on a community-by-community basis.[37] But to understand if New York is truly making progress in addressing the challenge of untreated serious mental illness, a closer look is necessary. That is the approach taken by Kendra’s Law. When Kendra’s Law was first enacted in the late 1990s, the concept of assisted outpatient treatment was new and controversial. Accordingly, the state mandated a rigorous program of monitoring that tracked outcomes such as homelessness and incarceration.[38] This has enabled researchers to document the success of Kendra’s Law.[39] OMH’s oversight regimen for Kendra’s Law also provides a model for how any program for seriously mentally ill individuals should be tracked.

Homelessness

Most of the city’s homeless population consists of families with children, and the extreme scarcity of rental apartments affordable to low-income New Yorkers is a leading cause. However, the number of seriously mentally ill homeless individuals, unsheltered and sheltered, has been rising in New York City (Figure 4).

As part of the assessment process, all entrants into the city’s homeless shelters receive a psychiatric evaluation. Many of those found to have serious mental illness are placed in a mental health shelter based on the recommendations of Department of Homeless Services (DHS) staff. Mental health shelters provide homeless single adults with on-site behavioral health and medical services, as well as linkages to further care in the community. The on-site behavioral-health services include individual and group therapy, medication management, and substance-abuse treatment.

At the end of FY 2018, New York City was operating 28 mental health shelters, a total capacity of 3,506 beds.[40] Though they don’t provide true “inpatient” care, mental health shelters have become one of the most substantial components of the public mental health-care system in the city, where total beds in mental health shelters exceed the combined total of adult beds in state psychiatric centers and inpatient psychiatric-care beds in the NYC Health + Hospitals system (Figure 5).

From FY 2014 to FY 2018, New York City opened six new mental health shelters: Julio’s Place and Pam’s Place, both run by Acacia; Prospect Place and Delta Manor, both run by the Center for Urban Community Services; East Tremont, run by the Neighborhood Association for Inter-Cultural Affairs; and The Renaissance, run by Services for the Underserved. (See Appendix for a list of all shelters, along with their bed counts and budgets.) Figure 6 shows that the city’s spending on mental health shelters has risen every year since FY 2014 and now stands at $150 million.

Criminal Justice

Deinstitutionalization has sometimes been described, critically, as “trans-institutionalization”: when the outpatient-oriented mental health-care system failed to provide adequate treatment for the seriously mentally ill, other government agencies were forced to bear a greater responsibility for addressing mental illness–related challenges. This effect is perhaps nowhere clearer than with respect to the criminal-justice system. Every state is home to a jail that hosts a larger population of seriously mentally ill individuals than is kept at the largest state psychiatric hospital in that same state.[41]

Figure 7 shows the situation in New York. (The Rockland Psychiatric Center currently has the largest census of all state psychiatric centers; Creedmoor has the largest census of any state psychiatric center in New York City.)[42] In New York, three state hospitals that were closed in the 1980s and 1990s (Gowanda State Hospital, Willard State Hospital, and Marcy State) were turned over for use by the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision.[43]

Untreated serious mental illness contributes to public disorder in New York City. Consider several examples. In May 2015, over a stretch of three days, David Baril was arrested for assaulting four people with a hammer, including a police officer.[44] Baril had been diagnosed for paranoid schizophrenia and, months before the assaults, had discharged himself from a group home for mentally ill adults. In July 2017, he was sentenced to 22 years in prison. In January 2016, Anthony White, a resident of a mental health shelter in Harlem, slit the throat of another shelter resident, Deven Black, killing and almost decapitating him.[45] The body of White, who had previously been hospitalized several times for psychiatric care, was later found in the Hudson River after his apparent suicide.

On a single afternoon in September 2018, Rickey Hayes robbed a Chinatown liquor store and assaulted the clerk, then robbed a shoe store in Greenwich Village and assaulted two employees there, one of whom was an 88-year-old woman. He was finally arrested trying to shoplift at Macy’s in Herald Square.[46] In speaking to reporters the next day, Hayes said: “I didn’t take my medication” (he had been taking Abilify, an antipsychotic drug).

In July 2018, Marcus Gomez, who had recently left the Creedmoor State Psychiatric Center, repeatedly stabbed a home health aide who had been caring for his grandmother.[47] In September 2018, a four-year-old boy was thrown to his death off a seven-story building in Midwood, Brooklyn.[48] The perpetrator was Shawn Smith, the victim’s brother, a schizophrenic who had been hospitalized for psychiatric treatment in July at Kings County Hospital but had stopped taking his medication. In explaining his motivations for the act, Smith said that he “wanted to see if God could protect the kid.”

In October 2018, David Aleer, an “emotionally disturbed homeless man,” approached a 64-year-old man in Bryant Park and repeatedly beat him with a bike lock.[49] The victim survived the attack but required hospitalization for his broken hands, eye socket, and major head laceration. David Felix, Deborah Danner, and Saheed Vassell were three seriously mentally ill individuals who died in violent altercations with the NYPD—in April 2015, October 2016, and April 2018, respectively.[50] NYPD Officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu were shot to death by an individual with a history of mental illness in December 2014, as were officers Brian Moore and Miosotis Familia in May 2015 and July 2017, respectively.[51] These are not the only mental illness–related tragedies that have been covered in the local news in the past five years.

The burden of untreated serious mental illness on the criminal-justice system may be quantitatively expressed in at least two ways: “emotionally disturbed person” calls for service; and the high rate of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Figure 8 shows that, in New York City, the number of police responses to “emotionally disturbed person” calls has grown every year since 2014, when OMH’s Transformation Plan began. Figure 9 shows that the number of seriously mentally ill inmates in city jails is higher now than in FY 2014.

City officials have responded to the mental health burden on its criminal-justice system in several ways. Many “alternative to incarceration” programs, such as mental health courts, divert low-level offenders out of jail and into probation-style treatment regimens. Indeed, as noted, New York City is said to offer one of the most robust networks of alternatives to incarceration in the U.S.[52]

The NYPD’s Crisis Intervention Training program is by now likely the largest in the nation, having trained almost 10,000 patrol officers since 2015 in how to “deescalate” encounters with emotionally disturbed individuals.[53] On Rikers Island, hundreds of corrections officers have also received crisis-intervention training; since 2013, the jail has also launched two separate initiatives (the Program for Accelerating Clinical Effectiveness and the Clinical Alternative to Punitive Segregation) that provide behavioral-health services to inmates with psychiatric disorders.

Through a combination of low levels of crime and political pressure to reduce the use of incarceration, the average daily population in New York City jails has declined from 22,000, in the early 1990s, to fewer than 9,000 today.[54] The Rikers Island jail complex is planned to be closed by 2027, to be replaced by a network of borough-based correctional facilities.[55] Some mental health advocates, such as journalist Alisa Roth, have raised doubts that adequate consideration is being given to the unique needs of the seriously mentally ill inmate population.[56] “De-incarceration” appears to be already contributing to the persistently rising numbers of homeless single adults in New York City.[57]

Mayor de Blasio’s “comprehensive” mental health initiative, Thrive NYC, has been criticized for its inattention to the unique challenge of untreated serious mental illness.[58] Though the de Blasio administration has often claimed that the program will address all manner of mental disorders, from the mild to the serious, Thrive NYC is best seen as an attempt to provide mental health care to disadvantaged populations, with “disadvantage” understood in a socioeconomic sense. Providing mental health services to populations that are disadvantaged by virtue of their mental illness is a different challenge.

City Hospitals

Deinstitutionalization had several causes. Within the state context, one motivation was to transfer at least some of the burden of psychiatric care to the local level.[59] One result of increased local responsibility was a greater role for inpatient psychiatric care assumed by general hospitals, which, as noted, were not major providers of inpatient psychiatric care before deinstitutionalization.[60] At present, there are about four times as many facilities that provide inpatient mental health care in the general hospital network than state psychiatric centers;[61] there are also more total beds in the general hospital network (Figure 1).

In terms of the roles that state psychiatric hospitals and general hospitals play in the mental health-care system, at least two important differences exist. First, state psychiatric centers are intended to provide longer-term care. General hospitals take patients in acute crisis and discharge them within a few days or weeks. As noted, New York’s 15 state psychiatric centers for non-forensic adult patients are currently home to 1,203 long-stay patients who have been hospitalized for a year or more, 529 of whom are in New York City.[62] In terms of the average daily census, that means slightly more than half the adult psychiatric-center population, in the facilities in New York City and statewide, are long-stay cases.[63] State psychiatric centers also have chief responsibility for treating extremely difficult or “specialized” cases, such as the criminally insane and sex offenders.[64]

The second important difference is that inpatient mental health care is funded differently at general hospitals, compared with state psychiatric centers. The latter are classified by the federal government as Institutions for Mental Diseases (IMD). An IMD is an inpatient facility with more than 16 beds, over half of whose patients are seriously mentally ill. Such facilities cannot bill Medicaid for the cost of care for people between the ages of 22 and 64. General hospitals, by contrast, are eligible for Medicaid funding.

General hospitals’ different financial structures played a major role in why they emerged as a vital source of inpatient psychiatric care over the latter decades of the 20th century, as state bed counts declined. But general hospitals ceased expanding their inpatient psychiatric capacity about 20 years ago. Between 1970 and 1998, the number of psychiatric beds in general hospitals nationwide rose from about 21,000 to nearly 55,000, but has since declined to 40,000.[65]

As is the case across the health-care industry and in many jurisdictions, New York is working to reduce the use of hospitals for all forms of care. In 2014, the Cuomo administration announced plans for the joint state-federal Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program, to reduce “avoidable hospital use,” including for mental health care, by 25% over five years for Medicaid patients.[66] OMH has described the Transformation Plan as “consistent with … ongoing reforms in health care policy and financing” that are designed to respond to how “the market for health care services becomes more consumer-directed, integrated and community-oriented.”[67]

NYC Health + Hospitals is the leading provider of inpatient psychiatric care in the city.[68] The 11 NYC Health + Hospitals facilities that provide inpatient psychiatric care for adults are host to 1,218 beds for that purpose, a total that exceeds the number of beds at state psychiatric centers in the city (1,058).[69] A 2017 analysis by the New York State Nurses Association found that NYC Health + Hospitals facilities accounted for only 20% of total staffed hospital beds in New York City, but 40%–60% of all discharges for serious mental disorders.[70]

The demand for inpatient psychiatric care at NYC Health + Hospitals facilities has been growing,[71] perhaps because of recent reductions in that service at the city’s voluntary hospitals. A 2017 report by New York City’s Independent Budget Office found that psychiatric hospitalizations at NYC Health + Hospitals facilities increased by about 4,000, or 20%, between 2010 and 2014. During the same period, mental health hospitalizations at the city’s voluntary hospitals fell by about 5%.[72]

Voluntary as well as NYC Health + Hospitals facilities can bill Medicaid for inpatient psychiatric services. Yet such services are reimbursed at rates that are lower than those for other procedures, such as major surgeries, and lower than what hospitals claim is the cost to provide them.[73] Hence, for example, the controversy of New York Presbyterian Hospital’s plan to “decertify”[74] 30 psychiatric beds at its Allen Hospital facility, beds that serve about 600 patients a year, and instead devote that capacity to “updat[ing] our Labor and Delivery and Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICU) and expand[ing] our surgical capacity.”[75] A petition to stop the closure of Allen Hospital has attracted more than 1,000 signatures.[76] Dozens of hospitals have closed during the past 20 years across the state, many of which provided psychiatric care.[77]

NYC Health + Hospitals has long faced fiscal challenges due to factors such as treating hundreds of thousands of patients each year who have no health insurance. Its deficit, already about $1 billion, is projected to almost double within the next five years as a result of cuts mandated by the Affordable Care Act to so-called Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments.[78]

Since the 1980s, public safety-net hospitals have received DSH payments from the federal government to compensate them for the care that they provide to Medicaid and uninsured patients. State government decides how to apportion these payments among hospitals. Though they’ve been repeatedly delayed, the looming DSH cuts have been a main focus of every recent report about financial strain at NYC Health + Hospitals.[79] (Voluntary hospitals are also major recipients of DSH payments.) Their bearing on psychiatric care—as well as that of NYC Health + Hospitals’ finances more generally—is indirect but significant. These fiscal pressures will make city hospitals and voluntary hospitals less well positioned to compensate for the state’s retreat from public inpatient psychiatric services.

Essentially two processes of deinstitutionalization are taking place, affecting state and general hospitals. These processes are being driven by different financial forces and, to some extent, affect different aspects of the inpatient mental health-care system. Still, the official justifications are essentially the same: better care at a lower cost. Although general hospitals, for a time, helped solve the problems created by deinstitutionalization, they are now contributing to the problem. Figure 10 shows the trend in recent bed reductions at general hospitals. Figure 11 shows the trend for all adult inpatient psychiatric beds in New York State and City.

Conclusion

What is the demand for inpatient psychiatric care in New York? Are the seriously mentally ill accessing the care that they need? Both OMH and representatives of general hospitals have recently spoken about excess capacity in, and expense associated with, New York’s inpatient mental health-care system.[80] But a seriously mentally ill individual lost in the depths of delusion and in need of inpatient treatment is not always going to ask for inpatient treatment. The number of seriously mentally ill individuals who are in jails or homeless is rising. And the sheer volume of mental illness–related tragedies that continue to make headlines attest that New York’s mental health-care system is failing to connect many individuals with treatment that’s intensive enough to properly address their psychiatric disorders.

As mentioned, New York City’s state psychiatric centers are home to only 529 long-stay cases.[81] About three times that number of seriously mentally ill individuals are living on city streets and 20 times that number in the shelter system (Figure 4). Is it possible that at least some of the thousands of seriously mentally ill homeless New Yorkers would benefit from a long stay in a psychiatric center? If so, state government should make a priority of expanding access to its inpatient mental health-care system instead of trying to reduce reliance on that system. Broadly speaking, reducing unnecessary levels of dependence on expensive government programs is a worthy goal. In the case of the mental health-care system, however, the more appropriate goal should be to increase use of the public safety net—even if that means a greater burden on the budgets of mental health-care agencies and general hospitals.

New York can claim many distinctions in the area of mental health. The 1890 State Care Act asserted the state’s responsibility over the burden of treating serious mental illness, making that challenge a top priority of the public sector.[82] In the mid-20th century, New York’s community-oriented approaches to treatment were widely emulated.[83] The national reputation of Kendra’s Law has been noted. But with respect to OMH’s Transformation Plan, the state is seeking to be more of a follower on mental health care. While New York’s bed count, by any measure, is higher than the U.S. average, the U.S. average is still far below that of other developed nations (Figure 12).

Despite rhetoric over “transforming” mental health in New York, state government’s current approach bears much resemblance to plans that have been under way for decades. The promise of “better care at lower cost” has been central to the case for deinstitutionalization from the beginning.[84] Deinstitutionalization’s contributions to homelessness and crime, including its burden on the criminal-justice system, raise questions about its design, execution, and cost-effectiveness.

Stretching back to the late 19th century, it was state government that had chief responsibility for caring for the seriously mentally ill. Though local institutions, such as community hospitals and city government, now have more responsibility than they did in the 1950s, their role is still secondary to that of state government. In short, if increasing access to inpatient mental health care is seen as central in efforts to address untreated serious mental illness, that will have to be more of a focus of state policymakers than it is for New York’s mayor and city council.

Under OMH’s Transformation Plan, New York City lost 183 beds in adult state psychiatric centers during 2014–18 (Figure 2), beds that are designed to meet the demand for long-term mental health hospitalization. This pales in comparison with the loss of 50,000 beds in the state network from, for example, 1968 to 1978.[85] In other words, over the decade prior to the early 1980s, when New York City began seriously debating homelessness, the state shed almost two-thirds of its psychiatric bed count in one decade. At present, criminal-justice and homeless-services systems would be grappling with the challenge of untreated serious mental illness had the state bed count been flat across recent years.

Though the recent reduction in beds may be much smaller than in past decades, the population that depends on inpatient psychiatric care is much sicker, on average, than the population cared for in state hospitals during the early phases of deinstitutionalization. At that time, as many as one-third of patients were elderly individuals suffering from dementia. Transferring them to new facilities, such as nursing homes, did not create significant pressures on other government agencies.[86] But by at least the 1980s, the only individuals in state hospitals were seriously mentally ill individuals, a population that is far more difficult to treat in a noninstitutional setting than the elderly.

Thus, a 12% drop in the 2010s is not necessarily easier to manage than a 60% drop in the 1970s—especially given the fact that general hospitals are no longer increasing their inpatient mental health-care capacity. Can a community-oriented mental health-care system maintain responsibility for the seriously mentally ill without unduly burdening the criminal-justice and homeless-services systems? By failing to demonstrate that such a goal is realistic, New York State is putting patients as well as the public at risk.

Endnotes

- New York State’s Office of Mental Health (OMH), “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” p. 50.

- Author’s calculations based on data from OMH.

- “Serious Mental Illness Among New York City Adults,” New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, June 2015; and OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” p. 6.

- OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 14.

- Ibid., pp. 41, 49.

- Forensic facilities, such as the Kirby Forensic Psychiatric Center on Ward’s Island, are mental hospitals used by the criminal-justice system. Patients are placed in these facilities after being found “Not Responsible for Criminal Conduct by Reason of Mental Disease or Defect” or to receive mental health services meant to restore them to a state of “competency” so that they can stand trial. As of July 2018, the number of forensic beds maintained by OMH numbers 744 and the average daily census is 640. See OMH, “Populations Served in OMH Forensic and SOTP Facilities.”

- Author’s calculations based on OMH monthly report for July 2018; and OMH, “New York State Chartbook of Mental Health Information 1996,” September 1996, table G-5.

- “Trend in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity, United States and Each State, 1970 to 2014,” National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, Assessment #10, August 2017, tables 1 and 13.

- Author’s calculations based on OMH, “New York State Chartbook of Mental Health Information 1996,” September 1996, table G-5; and “Trend in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity, United States and Each State, 1970 to 2014,” table 13.

- Morton M. Hunt, Mental Hospital (New York: Pyramid, 1962); and OMH, “Pilgrim Psychiatric Center.”

- Author’s calculations based on OMH monthly report for July 2018.

- “State Mental Health Agency-Controlled Expenditures for Mental Health Services, State Fiscal Year 2013,” NASMHPD Research Institute, Sept. 26, 2014, fig. 8.

- “Health, United States, 2016,” National Center for Health Statistics, 2017, p. 71.

- See, e.g., OMH, “Creedmoor Psychiatric Center Outpatient Services.”

- “Grading the States: An Analysis of Involuntary Psychiatric Treatment Laws,” Treatment Advocacy Center, September 2018.

- “Olmstead: Community Integration for Every New Yorker,” NY.gov.

- Jeffrey Geller, “The Last Half-Century of Psychiatric Services as Reflected in Psychiatric Services,” Psychiatric Services 51, no. 1 (January 2000): 41–67; Mark Olfson and David Mechanic, “Mental Disorders in Public, Private Nonprofit, and Proprietary General Hospitals,” American Journal of Psychiatry 153, no. 12 (December 1996): 1613–19; Benjamin Liptzin, Gary L. Gottlieb, and Paul Summergrad, “The Future of Psychiatric Services in General Hospitals,” American Journal of Psychiatry 164, no. 10 (October 2007): 1468–72; and David Mechanic, Donna McAlpine, and Mark Olfson, “Changing Patterns of Psychiatric Inpatient Care in the United States, 1988–1994,” Archives of General Psychiatry 55, no. 9 (September 1998): 785–91.

- Liptzin, Gottlieb, and Summergrad, “The Future of Psychiatric Services in General Hospitals,” fig. 1; and “Trend in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity, United States and Each State, 1970 to 2014,” table 9.

- “Trend in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity, United States and Each State, 1970 to 2014,” table 1.

- Author’s calculations based on OMH monthly report for July 2018; and OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” pp. 11–12. Statewide, there are also 1,123 beds for children (343 in state psychiatric centers, 451 in general hospitals, and 329 in private “Article 31” facilities).

- OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” p. 49.

- “National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2017 Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, August 2018, pp. 20–21.

- “Trend in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity, United States and Each State, 1970 to 2014,” p. 39. The states with a higher rate were Mississippi (55.4) and Missouri (59.6).

- Doris A. Fuller et al., “Going, Going, Gone: Trends and Consequences of Eliminating State Psychiatric Beds, 2016 Updated for Q2 Data,” Treatment Advocacy Center, June 2016, table 2.

- “The Cost of Mental Illness: New York Facts and Figures,” pp. 16–17.

- “State Mental Health Agency-Controlled Expenditures for Mental Health Services, State Fiscal Year 2013,” table 1.

- Author’s calculations based on data from the 2017 U.S. Census and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s HUD Exchange.

- Martin Horn and Brian Fischer, “The Risk of Replicating Rikers: Inmates with Mental Illness Need Help, Not Jail,” New York Daily News, Aug. 16, 2018.

- “The Cost of Mental Illness: New York Facts and Figures,” pp. 27–30.

- Author’s calculations based on data from “National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2017 Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities” and 2017 U.S. Census population estimates.

- D.J. Jaffe and E. Fuller Torrey, “Funds for Treating Individuals with Mental Illness: Is Your State Generous or Stingy?” MentalIllnessPolicy.org, Dec. 12, 2017.

- OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020”; and “FY19 Executive Budget Briefing Book,” New York State Office of the Governor, pp. 106–7.

- OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” p. 49.

- Glynis Hart, “Governor Reverses Closure of Binghamton, Elmira Psychiatric Centers,” Ithaca.com, Dec. 20, 2013; and Joseph Spector, “Moratorium on Closing State’s Psychiatric Centers Backed in Legislature,” Democrat and Chronicle, June 18, 2014.

- OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” p. 49.

- See https://www.omh.ny.gov/omhweb/transformation.

- See https://my.omh.ny.gov/analytics/saw.dll?dashboard.

- See discussion in Stephen Eide, “Assisted Outpatient Treatment in New York State: The Case for Making Kendra’s Law Permanent,” Manhattan Institute,

April 2017, pp. 8–9. - New York City Department of Homeless Services.

- E. Fuller Torrey et al., “More Mentally Ill Persons Are in Jails and Prisons than Hospitals: A Survey of the States,” Treatment Advocacy Center, May 2010.

- Author’s calculations based on OMH monthly report for July 2018.

- E. Fuller Torrey, “Albany Psychosis,” City Journal, Autumn 2014.

- “David Baril, Suspect in Hammer-Attacks, Has History of Mental Illness,” Pix11.com, May 13, 2015; and Colin Moynihan, “Hammer Attacker Sentenced to 22 Years in Prison,” New York Times, July 19, 2017.

- Kim Barker, Michael Schwirtz, and Lisa W. Foderaro, “2 Lives Collide in Fatal Night at a Harlem Shelter,” New York Times, Jan. 29, 2016; and Natalie O’Neill, “Murdered Homeless Ex-Teacher Had Rare Brain Disease,” New York Post, Apr. 10, 2017.

- Ellen Moynihan et al., “See It: Bald Bandit Bashes Manhattan Liquor Store Worker with Bottles, Pummels Two Elderly Shoe Store Workers,” New York Daily News, Sept. 10, 2018; and Nora Abramov and Nicole Johnson, “Arrest Made in Violent Lower Manhattan Robberies That Left 2 Hospitalized,” Pix11.com, Sept. 11, 2018.

- Checkey Beckford, “Shocking Video Shows Bleeding Home Health Attendant Stumbling Around After Being Stabbed Repeatedly,” nbcnewyork.com, July 31, 2018.

- Larry Celona, Amanda Woods, and Ruth Weissmann, “4-Year-Old Dead After Brother Shoves Him from Building: Cops,” New York Post, Sept. 29, 2018; and Tina Moore, Kevin Sheehan, and Larry Celona, “Man Who Threw Brother from Roof Had History of Mental Illness: Mom,” New York Post, Sept. 30, 2018.

- Kerry Burke, “Homeless Man Busted in Random Bike Lock Beat Down in Bryant Park,” New York Daily News, Oct. 19, 2018.

- J. David Goodman, “Suspect Fatally Shot by Detective in East Village Had Mental Illness and a Troubled Past,” New York Times, Apr. 26, 2015; Kenneth J. Dudek, “A Collective Failure,” FountainHouse.org, Oct. 26, 2016; and Benjamin Mueller and Nate Schweber, “Police Fatally Shoot a Brooklyn Man, Saying They Thought He Had a Gun,” New York Times, Apr. 4, 2018.

- C. J. Sullivan et al., “Kin Knew Cop Killer Was Ticking Time Bomb,” New York Post, Dec. 21, 2014; Jennifer Bain and Emily Saul, “Accused Cop Killer Suffers from Psychosis: Neuropsychologist,” New York Post, Nov. 1, 2017; and Benjamin Mueller and Al Baker, “Police Officer Is ‘Murdered for Her Uniform’ in the Bronx,” New York Times, July 5, 2017.

- Horn and Fischer, “The Risk of Replicating Rikers.”

- “Mayor’s Management Report, Fiscal 2018,” Mayor’s Office of Operations, p. 42; and Stephen Eide and Carolyn Gorman, “CIT and Its Limits,” City Journal, Summer 2017.

- “The City of New York Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the Comptroller for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2001,” Office of the Comptroller, Oct. 30, 2001, p. 258; and “Mayor’s Management Report, Fiscal 2018,” p. 83.

- “Our Plan Is to Close Rikers Island and Replace It with a Smaller Network of Modern Jails,” City of New York.

- Alisa Roth, “Shutter Island: At Rikers, People with Mental Illness Fall Through the Cracks Over and Over Again,” New York Daily News, Apr. 8, 2018.

- Brendan Cheney, “Single Adults in Homeless Shelters Are on the Rise,” Politico New York, Sept. 20, 2018.

- See, e.g., D.J. Jaffe, “Bad Medicine,” City Journal, Aug. 5, 2015; and “The City’s Dangerous Mental-Health Dodge,” New York Post, Nov. 15, 2015.

- Bonita Weddle, “Mental Health in New York State 1945–1998: An Historical Overview,” New York State Archives, 1998, p. 10.

- Liptzin, Gottlieb, and Summergrad, “The Future of Psychiatric Services in General Hospitals.”

- OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” p. 10.

- Author’s calculations based on OMH, “Monthly Report, July 2018.”

- Ibid.; and OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” p. 49.

- William H. Fisher, Jeffrey L. Geller, and John A. Pandiani, “The Changing Role of the State Psychiatric Hospital,” Health Affairs 28, no. 3 (May/June 2009): 676–84; and “The Vital Role of State Psychiatric Hospitals,” National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, July 2014.

- “Health, United States, 2011,” National Center for Health Statistics, 2012, p. 358, table 117; and Liptzin, Gottlieb, and Summergrad, “The Future of Psychiatric Services in General Hospitals,” fig. 1.

- “DSRIP Overview”; and Douglas G. Fish, “Behavioral Health and Primary Care in the DSRIP Program: Integrating Two Worlds,” New York State Department of Health, July 21, 2016.

- OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” p. 50.

- “Testimony of Charles Barron, M.D., Deputy Chief Medical Officer, NYC Health + Hospitals,” “Off-Site Hearing: Oversight—The Future of Psychiatric Care in New York City’s Hospital Infrastructure: Hearing Testimony.”

- Author’s calculations based on OMH, “Monthly Report, July 2018.”

- Barbara Caress and James Parrott, “On Restructuring the NYC Health + Hospitals Corporation Preserving and Expanding Access to Care for All New Yorkers,” New York State Nurses Association, October 2017, charts 10 and 14.

- “Reenvisioning Clinical Infrastructure Recommendations on NYC Health + Hospitals’ Transformation,” Commission on Health Care for Our Neighborhoods, March 2017, pp. 4, 6.

- “Are New York City’s Public Hospitals Becoming the Main Provider of Inpatient Services for the Mentally Ill?” Independent Budget Office, July 2017.

- Caress and Parrott, “On Restructuring the NYC Health + Hospitals Corporation,” pp. 23, 34; and “Testimony of Charles Barron,” p. 8.

- See OMH, “Prior Approval Review.”

- New York City Council, “Off-Site Hearing: Oversight—The Future of Psychiatric Care in New York City’s Hospital Infrastructure.” Regarding the New York Presbyterian proposal, David Rich, a spokesman for the Greater New York Hospital Association, a trade group representing general hospitals, said:

“[T]hese changes reflect the above-described shift away from inpatient and towards community-based care. In addition, demand for traditional psychiatric beds is going down overall and some institutions have excess capacity. Given limited resources, it makes sense to repurpose excess capacity to provide other important community services, including ambulatory psychiatric care, that better reflect the latest clinical advances and community needs…. [E]very hospital in New York City is transitioning towards community-based outpatient care…. [S]ome systems are further along than others.” - See, e.g., “Protect the Allen Hospital’s Community Mission,” Change.org.

- Lois Uttley et al., “Empowering New York Consumers in an Era of Hospital Consolidation,” New York State Health Foundation, May 2018, tables 1–3. Examples of facilities that have closed entirely in recent decades that provided inpatient psychiatric care include Harlem Valley, Gowanda, Central Islip, Willard, and King’s Park (all state psychiatric centers in the 1990s) and New York Westchester Square Medical Center, North General Hospital, Peninsula Hospital Center, and St. Vincent’s Manhattan (Weddle, “Mental Health in New York State 1945–1998”; and e-mail correspondence with Independent Budget Office).

- “Financial Plan—Submission to the Financial Control Board,” Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, June 14, 2018, exhibit B-1; and “Report of the Finance Division on the Fiscal 2019 Preliminary Budget and the Fiscal 2018 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report for the New York City Health and Hospitals,” New York City Council Finance Division, Mar. 15, 2018, pp. 3, 9–10.

- Caress and Parrott, “On Restructuring the NYC Health + Hospitals Corporation,” p. 30; “Holes in the Safety Net: Obamacare and the Future of New York City’s Health & Hospitals Corporation,” New York City Comptroller’s Office, May 2015; Roosa Tikkanen, “Funding Charity Care in New York: An Examination of Indigent Care Pool Allocations,” New York State Health Foundation, March 2017; “Sustaining the Safety Net Recommendations on NYC Health + Hospitals’ Transformation,” Commission on Health Care for Our Neighborhoods, March 2017; “One New York, Health Care for Our Neighborhoods: Transforming Health + Hospitals,” Office of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, 2016; Robert W. Glover and Joel E. Miller, “The Interplay Between Medicaid DSH Payment Cuts, the IMD Exclusion and the ACA Medicaid Expansion Program: Impacts on State Public Mental Health Services,” National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, Apr. 13, 2013; Patrick Orecki, “Medicaid Supplemental Payments,” Citizens Budget Commission, Aug. 31, 2017; and idem, “DSH Cuts Delayed,” Citizens Budget Commission, Apr. 11, 2018.

- OMH, “Statewide Comprehensive Plan 2016–2020,” pp. 15, 48–50; idem, “FY 2019 Executive Budget Briefing Book,” pp. 101–10; “Testimony of David Rich, Executive Vice President, Government Affairs, Communications & Public Policy, Greater New York Hospital Association,” New York City Council, “Off-Site Hearing: Oversight—The Future of Psychiatric Care in New York City’s Hospital Infrastructure.”

- Author’s calculations based on OMH monthly report for July 2018.

- Weddle, “Mental Health in New York State 1945–1998,” p. 2.

- Ibid., pp. 8ff.; and Torrey, “Albany Psychosis.”

- E. Fuller Torrey, The Insanity Offense: How America’s Failure to Treat the Seriously Mentally Ill Endangers Its Citizens (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), chaps. 3–4; and Weddle, “Mental Health in New York State 1945–1998,” pp. 3, 8.

- There were 78,011 patients in the state system in 1968 but only 27,866 in 1978. Author’s calculations based on data from “New York State Chartbook of Mental Health Information 1996.”

- Ann Braden Johnson, Unravelling of a Social Policy: The History of the Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill in New York State (New York: New York University Press, 1986), pp. 206–7.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).